Schröder–Bernstein theorem

In set theory, the Schröder–Bernstein theorem (named after Felix Bernstein and Ernst Schröder, also known as Cantor–Bernstein theorem, or Cantor–Schröder–Bernstein after Georg Cantor who first published it without proof) states that, if there exist injective functions f : A → B and g : B → A between the sets A and B, then there exists a bijective function h : A → B. In terms of the cardinality of the two sets, this means that if |A| ≤ |B| and |B| ≤ |A|, then |A| = |B|; that is, A and B are equipollent. This is a useful feature in the ordering of cardinal numbers.

This theorem does not rely on the axiom of choice. However, its various proofs are non-constructive, as they depend on the law of excluded middle, and are therefore rejected by intuitionists.[1]

Proof

The following proof is attributed to Julius König.[2]

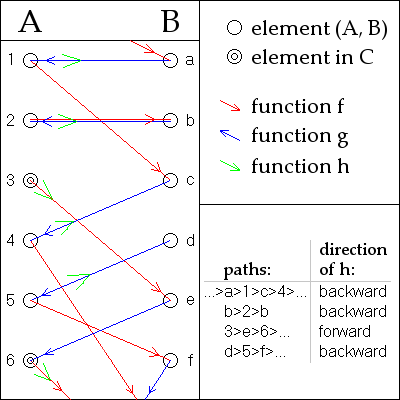

Assume without loss of generality that A and B are disjoint. For any a in A or b in B we can form a unique two-sided sequence of elements that are alternately in A and B, by repeatedly applying and to go right and and to go left (where defined).

For any particular a, this sequence may terminate to the left or not, at a point where or is not defined.

By the fact that and are injective functions, each a in A and b in B is in exactly one such sequence to within identity: if an element occurs in two sequences, all elements to the left and to the right must be the same in both, by the definition of the sequences. Therefore, the sequences form a partition of the (disjoint) union of A and B. Hence it suffices to produce a bijection between the elements of A and B in each of the sequences separately, as follows:

Call a sequence an A-stopper if it stops at an element of A, or a B-stopper if it stops at an element of B. Otherwise, call it doubly infinite if all the elements are distinct or cyclic if it repeats. See the picture for examples.

- For an A-stopper, the function is a bijection between its elements in A and its elements in B.

- For a B-stopper, the function is a bijection between its elements in B and its elements in A.

- For a doubly infinite sequence or a cyclic sequence, either or will do ( is used in the picture).

Original proof

An earlier proof by Cantor relied, in effect, on the axiom of choice by inferring the result as a corollary of the well-ordering theorem.[3] The argument given above shows that the result can be proved without using the axiom of choice.

Furthermore, there is a proof which uses Tarski's fixed point theorem.[4]

History

The traditional name "Schröder–Bernstein" is based on two proofs published independently in 1898. Cantor is often added because he first stated the theorem in 1887, while Schröder's name is often omitted because his proof turned out to be flawed while the name of Richard Dedekind, who first proved it, is not connected with the theorem. According to Bernstein, Cantor had suggested the name equivalence theorem (Äquivalenzsatz).[5]

- 1887 Cantor publishes the theorem, however without proof.[6][5]

- 1887 On July 11, Dedekind proves the theorem (not relying on the axiom of choice)[7] but neither publishes his proof nor tells Cantor about it. Ernst Zermelo discovered Dedekind's proof and in 1908[8] he publishes his own proof based on the chain theory from Dedekind's paper Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen?[5][9]

- 1895 Cantor states the theorem in his first paper on set theory and transfinite numbers. He obtains it as an easy consequence of the linear order of cardinal numbers.[10][11] However, he couldn't prove the latter theorem, which is shown in 1915 to be equivalent to the axiom of choice by Friedrich Moritz Hartogs.[5][12]

- 1896 Schröder announces a proof (as a corollary of a theorem by Jevons).[13]

- 1896 Schröder publishes a proof sketch[14] which, however, is shown to be faulty by Alwin Reinhold Korselt in 1911[15] (confirmed by Schröder).[5][16]

- 1897 Bernstein, a 19 years old student in Cantor's Seminar, presents his proof.[17][18]

- 1897 Almost simultaneously, but independently, Schröder finds a proof.[17][18]

- 1897 After a visit by Bernstein, Dedekind independently proves the theorem a second time.

- 1898 Bernstein's proof (not relying on the axiom of choice) is published by Émile Borel in his book on functions.[19] (Communicated by Cantor at the 1897 International Congress of Mathematicians in Zürich.) In the same year, the proof also appears in Bernstein's dissertation.[20][5]

Both proofs of Dedekind are based on his famous memoir Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen? and derive it as a corollary of a proposition equivalent to statement C in Cantor's paper,[10] which reads A ⊆ B ⊆ C and |A|=|C| implies |A|=|B|=|C|. Cantor observed this property as early as 1882/83 during his studies in set theory and transfinite numbers and was therefore (implicitly) relying on the Axiom of Choice.

See also

- Myhill isomorphism theorem

- Schröder–Bernstein theorem for measurable spaces

- Schröder–Bernstein theorems for operator algebras

- Schröder–Bernstein property

Notes

- ↑ Ettore Carruccio (2006). Mathematics and Logic in History and in Contemporary Thought. Transaction Publishers. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-202-30850-0.

- ↑ J. König (1906). "Sur la théorie des ensembles". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences. 143: 110–112.

- ↑ Georg Cantor (1895). "Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre (1)". Mathematische Annalen. 46: 481–512. doi:10.1007/bf02124929.

Georg Cantor (1897). "Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre (2)". Mathematische Annalen. 49: 207–246. doi:10.1007/bf01444205. - ↑ R. Uhl, "Tarski's Fixed Point Theorem", from MathWorld–a Wolfram Web Resource, created by Eric W. Weisstein. (Example 3)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Felix Hausdorff (2002), Egbert Brieskorn; Srishti D. Chatterji; et al., eds., Grundzüge der Mengenlehre (1. ed.), Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, p. 587, ISBN 3-540-42224-2 - Original edition (1914)

- 1 2 Georg Cantor (1887), "Mitteilungen zur Lehre vom Transfiniten", Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik, 91: 81–125

Reprinted in: Georg Cantor (1932), Adolf Fraenkel (Lebenslauf); Ernst Zermelo, eds., Gesammelte Abhandlungen mathematischen und philosophischen Inhalts, Berlin: Springer, pp. 378–439 Here: p.413 bottom - ↑ Richard Dedekind (1932), Robert Fricke; Emmy Noether; Øystein Ore, eds., Gesammelte mathematische Werke, 3, Braunschweig: Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn, pp. 447–449 (Ch.62)

- ↑ Ernst Zermelo (1908), Felix Klein; Walther von Dyck; David Hilbert; Otto Blumenthal, eds., "Untersuchungen über die Grundlagen der Mengenlehre I", Mathematische Annalen, Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 65 (2): 261–281; here: p.271–272, ISSN 0025-5831, doi:10.1007/bf01449999

- ↑ Richard Dedekind (1888), Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen? (2., unchanged (1893) ed.), Braunschweig: Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn

- 1 2 Georg Cantor (1932), Adolf Fraenkel (Lebenslauf); Ernst Zermelo, eds., Gesammelte Abhandlungen mathematischen und philosophischen Inhalts, Berlin: Springer, pp. 285 ("Satz B")

- ↑ Georg Cantor (1895). "Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre (1)". Mathematische Annalen. 46: 481–512 (Theorem see "Satz B", p.484). doi:10.1007/bf02124929.

(Georg Cantor (1897). "Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre (2)". Mathematische Annalen. 49: 207–246. doi:10.1007/bf01444205.) - ↑ Friedrich M. Hartogs (1915), Felix Klein; Walther von Dyck; David Hilbert; Otto Blumenthal, eds., "Über das Problem der Wohlordnung", Mathematische Annalen, Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 76 (4): 438–443, ISSN 0025-5831, doi:10.1007/bf01458215

- ↑ Ernst Schröder (1896). "Über G. Cantorsche Sätze". Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung. 5: 81–82.

- ↑ Ernst Schröder (1898), Kaiserliche Leopoldino-Carolinische Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher, ed., "Ueber zwei Definitionen der Endlichkeit und G. Cantor’sche Sätze", Nova Acta, Halle a. S.: Johann Ambrosius Barth Verlag, 71 (6): 303–376 (proof: p.336–344)

- ↑ Alwin R. Korselt (1911), Felix Klein; Walther von Dyck; David Hilbert; Otto Blumenthal, eds., "Über einen Beweis des Äquivalenzsatzes", Mathematische Annalen, Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 70 (2): 294–296, ISSN 0025-5831, doi:10.1007/bf01461161

- ↑ Korselt (1911), p.295

- 1 2 Oliver Deiser (2010), Einführung in die Mengenlehre - Die Mengenlehre Georg Cantors und ihre Axiomatisierung durch Ernst Zermelo (3rd, corrected ed.), Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 71, 501, ISBN 978-3-642-01444-4, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01445-1

- 1 2 Patrick Suppes (1972), Axiomatic Set Theory (1. ed.), New York: Dover Publications, pp. 95 f., ISBN 0-486-61630-4

- ↑ Émile Borel (1898), Leçons sur la théorie des fonctions, Paris: Gauthier-Villars et fils, pp. 103 ff.

- ↑ Felix Bernstein (1901), Untersuchungen aus der Mengenlehre, Halle a. S.: Buchdruckerei des Waisenhauses

Reprinted in: Felix Bernstein (1905), Felix Klein; Walther von Dyck; David Hilbert, eds., "Untersuchungen aus der Mengenlehre", Mathematische Annalen, Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 61 (1): 117–155, (Theorem see "Satz 1" on p.121), ISSN 0025-5831, doi:10.1007/bf01457734

References

- Proofs from THE BOOK, p. 90. ISBN 3-540-40460-0

- Hinkis, Arie (2013), Proofs of the Cantor-Bernstein theorem. A mathematical excursion, Science Networks. Historical Studies, 45, Heidelberg: Birkhäuser/Springer, ISBN 978-3-0348-0223-9, MR 3026479, doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-0224-6

External links

- Cantor-Schroeder-Bernstein theorem in nLab

- Cantor-Bernstein’s Theorem in a Semiring by Marcel Crabbé.

- This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Schröder-Bernstein_theorem", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.