Kimono

The kimono (着物, きもの)[1] is a traditional Japanese garment. The word "kimono", which actually means a "thing to wear" (ki "wear" and mono "thing"),[2] has come to denote these full-length robes. The standard plural of the word kimono in English is kimonos,[3] but the unmarked Japanese plural kimono is also used. The kimono is always worn for important festivals or formal occasions. It is a formal style of clothing associated with politeness and good manners.

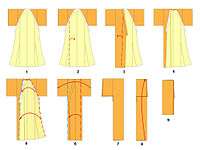

Kimono have T-shaped, straight-lined robes worn so that the hem falls to the ankle, with attached collars and long, wide sleeves. Kimono are wrapped around the body, always with the left side over the right (except when dressing the dead for burial)[4] and are secured by a sash called an obi, which is tied at the back. Kimono are generally worn with traditional footwear (especially zōri or geta) and split-toe socks (tabi).[5]

Today, kimono are most often worn by women, particularly on special occasions. Traditionally, unmarried women wore a style of kimono called furisode,[5] with almost floor-length sleeves, on special occasions. A few older women and even fewer men still wear the kimono on a daily basis. Men wear the kimono most often at weddings, tea ceremonies, and other very special or very formal occasions. Professional sumo wrestlers are often seen in the kimono because they are required to wear traditional Japanese dress whenever appearing in public.[6]

History

.jpg)

Chinese fashion had a huge influence on Japan from the Kofun period to the early Heian period as a result of mass immigration from the continent and a Japanese envoy to Tang Dynasty. During Japan's Heian period (794–1192 AD), the kimono became increasingly stylized, though one still wore a half-apron, called a mo, over it.[5] During the Muromachi age (1392–1573 AD), the Kosode, a single kimono formerly considered underwear, began to be worn without the hakama (trousers, divided skirt) over it, and thus began to be held closed by an obi "belt".[5] During the Edo period (1603–1867 AD), the sleeves began to grow in length, especially among unmarried women, and the Obi became wider, with various styles of tying coming into fashion.[5] Since then, the basic shape of both the men’s and women’s kimono has remained essentially unchanged. Kimonos made with exceptional skill from fine materials have been regarded as great works of art.[5]

The formal kimono was replaced by the more convenient Western clothes and yukata as everyday wear. After an edict by Emperor Meiji,[9] police, railroad men and teachers moved to Western clothes. The Western clothes became the army and school uniform for boys. After the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, kimono wearers often became victims of robbery because they could not run very fast due to the restricting nature of the kimono on the body and geta clogs. The Tokyo Women's & Children's Wear Manufacturers' Association (東京婦人子供服組合) promoted Western clothes. Between 1920 and 1930 the sailor outfit replaced the undivided hakama in school uniforms for girls. The 1932 fire at Shirokiya's Nihonbashi store is said to have been the catalyst for the decline in kimonos as everyday wear. Kimono-clad Japanese women did not wear underwear and several women refused to jump into safety nets because they were ashamed of being seen from below. (It is, however, suggested, that this is an urban myth.)[10][11] The national uniform, Kokumin-fuku, a type of Western clothes, was mandated for males in 1940.[12][13][14] Today most people wear Western clothes and wear the breezier and more comfortable yukata for special occasions.

In the Western world, kimono-styled women's jackets, similar to a casual cardigan,[15] gained public attention as a popular fashion item in 2014.[16]

Textiles and manufacture

Kimonos for men should fall approximately to the ankle without tucking. A woman's kimono has additional length to allow for the ohashori, the tuck that can be seen under the obi, which is used to adjust the kimono to the wearer. An ideally tailored kimono has sleeves that fall to the wrist when the arms are lowered.

Kimonos are traditionally made from a single bolt of fabric called a tan. Tan come in standard dimensions—about 36 centimetres wide and 11.5 metres long[5]—and the entire bolt is used to make one kimono. The finished kimono consists of four main strips of fabric—two panels covering the body and two panels forming the sleeves—with additional smaller strips forming the narrow front panels and collar.[5] Historically, kimonos were often taken apart for washing as separate panels and resewn by hand. Because the entire bolt remains in the finished garment without cutting, the kimono can be retailored easily to fit another person.[5]

The maximum width of the sleeve is dictated by the width of the fabric. The distance from the center of the spine to the end of the sleeve could not exceed twice the width of the fabric. Traditional kimono fabric was typically no more than 36 centimeters (14 inches) wide. Thus the distance from spine to wrist could not exceed a maximum of roughly 68 centimeters (27 inches). Modern kimono fabric is woven as wide as 42 centimeters (17 inches) to accommodate modern Japanese body sizes. Very tall or heavy people, such as sumo wrestlers, must have kimonos custom-made by either joining multiple bolts, weaving custom-width fabric, or using non-standard size fabric.[17]

Traditionally, kimonos are sewn by hand; even machine-made kimonos require substantial hand-stitching. Kimono fabrics are frequently hand-made and -decorated. Techniques such as yūzen dye resist are used for applying decoration and patterns to the base cloth. Repeating patterns that cover a large area of a kimono are traditionally done with the yūzen resist technique and a stencil. Over time there have been many variations in color, fabric and style, as well as accessories such as the obi.

The kimono and obi are traditionally made of hemp, linen, silk, silk brocade, silk crepes (such as chirimen) and satin weaves (such as rinzu). Modern kimonos are widely available in less-expensive easy-care fabrics such as rayon, cotton sateen, cotton, polyester and other synthetic fibers. Silk is still considered the ideal fabric.

Customarily, woven patterns and dyed repeat patterns are considered informal. Formal kimonos have free-style designs dyed over the whole surface or along the hem.[5] During the Heian period, kimonos were worn with up to a dozen or more colorful contrasting layers, with each combination of colors being a named pattern.[5] Today, the kimono is normally worn with a single layer on top of one or more undergarments.

The pattern of the kimono can determine in which season it should be worn. For example, a pattern with butterflies or cherry blossoms would be worn in spring. Watery designs are common during the summer. A popular autumn motif is the russet leaf of the Japanese maple; for winter, designs may include bamboo, pine trees and plum blossoms.

A popular form of textile art in Japan is shibori (intricate tie dye), found on some of the more expensive kimonos and haori kimono jackets. Patterns are created by minutely binding the fabric and masking off areas, then dying it, usually by hand. When the bindings are removed, an undyed pattern is revealed. Shibori work can be further enhanced with yuzen (hand applied) drawing or painting with textile dyes or with embroidery; it is then known as tsujigahana. Shibori textiles are very time-consuming to produce and require great skill, so the textiles and garments created from them are very expensive and highly prized.

Old kimonos are often recycled in: altered to make haori, hiyoku, or kimonos for children; used to patch similar kimono; used for making handbags and similar kimono accessories; and used to make covers, bags or cases for implements, especially for sweet-picks used in tea ceremonies. Damaged kimonos can be disassembled and resewn to hide the soiled areas, and those with damage below the waistline can be worn under a hakama. Historically, skilled craftsmen laboriously picked the silk thread from old kimono and rewove it into a new textile in the width of a heko obi for men's kimono, using a recycling weaving method called saki-ori.

Parts

These terms refer to parts of a kimono:

- Dōura (胴裏): upper lining on a woman's kimono.

- Eri (衿): collar.

- Fuki (袘): hem guard.

- Sode (袖): sleeve below the armhole.

- Obi (帯): a belt used to tuck excess cloth away from the seeing public.

- Maemigoro (前身頃): front main panel, excluding sleeves. The covering portion of the other side of the back, maemigoro is divided into "right maemigoro" and "left maemigoro".

- Miyatsukuchi (身八つ口): opening under the sleeve.

- Okumi (衽): front inside panel on the front edge of the left and right, excluding the sleeve of a kimono. Until the collar, down to the bottom of the dress goes, up and down part of the strip of cloth. Have sewn the front body. It is also called "袵".

- Sode (袖): sleeve.[5]

- Sodeguchi (袖口): sleeve opening.

- Sodetsuke (袖付): kimono armhole.

- Susomawashi (裾回し): lower lining.

- Tamoto (袂): sleeve pouch.

- Tomoeri (共衿): over-collar (collar protector).

- Uraeri (裏襟): inner collar.

- Ushiromigoro (後身頃): back main panel, excluding sleeves, covering the back portion. They are basically sewn back-centered and consist of "right ushiromigoro" and "left ushiromigoro", but for wool fabric, the ushiromigoro consists of one piece.

Cost

A woman's kimono may easily exceed US$10,000;[18] a complete kimono outfit, with kimono, undergarments, obi, ties, socks, sandals, and accessories, can exceed US$20,000. A single obi may cost several thousand dollars. However, most kimonos owned by kimono hobbyists or by practitioners of traditional arts are far less expensive. Enterprising people make their own kimono and undergarments by following a standard pattern, or by recycling older kimonos. Cheaper and machine-made fabrics can substitute for the traditional hand-dyed silk. There is also a thriving business in Japan for second-hand kimonos, which can cost as little as ¥500 (about $6). Women's obi, however, mostly remain an expensive item. Although simple patterned or plain colored ones can cost as little as ¥1,500 (about $18), even a used obi can cost hundreds of dollars, and experienced craftsmanship is required to make them. Men's obi, even those made from silk, tend to be much less expensive, because they are narrower, shorter and less decorative than those worn by women.

Styles

Kimonos range from extremely formal to casual. The level of formality of women's kimono is determined mostly by the pattern of the fabric, and color. Young women's kimonos have longer sleeves, signifying that they are not married, and tend to be more elaborate than similarly formal older women's kimono.[5] Men's kimonos are usually one basic shape and are mainly worn in subdued colors. Formality is also determined by the type and color of accessories, the fabric, and the number or absence of kamon (family crests), with five crests signifying extreme formality.[5] Silk is the most desirable, and most formal, fabric. Kimonos made of fabrics such as cotton and polyester generally reflect a more casual style.

Women's kimono

Many modern Japanese women lack the skill to put on a kimono unaided: the typical woman's kimono outfit consists of twelve or more separate pieces that are worn, matched, and secured in prescribed ways, and the assistance of licensed professional kimono dressers may be required. Called upon mostly for special occasions, kimono dressers both work out of hair salons and make house calls.

Choosing an appropriate type of kimono requires knowledge of the garment's symbolism and subtle social messages, reflecting the woman's age, marital status, and the level of formality of the occasion.

Furisode

Furisode (振袖) literally translates as swinging sleeves—the sleeves of furisode average between 39 and 42 inches (110 cm) in length. Furisode are the most formal kimono for unmarried women, with colorful patterns that cover the entire garment. They are usually worn at coming-of-age ceremonies (seijin shiki) and by unmarried female relatives of the bride at weddings and wedding receptions.

Hōmongi

Hōmongi (訪問着) literally translates as visiting wear. Characterized by patterns that flow over the shoulders, seams and sleeves, hōmongi rank slightly higher than their close relative, the tsukesage. Hōmongi may be worn by both married and unmarried women; often friends of the bride will wear hōmongi at weddings (except relatives) and receptions. They may also be worn to formal parties.

Pongee Hōmongi were made to promote kimono after WWII. Since Pongee Hōmongi are made from Pongee, they are considered casual wear.

Iromuji

Iromuji (色無地) are colored kimono that may be worn by married and unmarried women. They are mainly worn to tea ceremonies. The dyed silk may be figured (rinzu, similar to jacquard), but has no differently colored patterns. It comes from the word "muji" which means plain or solid and "iro" which means color.

Komon

Komon (小紋) means "fine pattern". The term refers to kimono with a small, repeated pattern throughout the garment. This style is more casual and may be worn around town, or dressed up with a formal obi for a restaurant. Both married and unmarried women may wear komon.

Edo komon

Edo komon (江戸小紋) is a type of komon characterized by tiny dots arranged in dense patterns that form larger designs. The Edo komon dyeing technique originated with the samurai class during the Edo period. A kimono with this type of pattern is of the same formality as an iromuji, and when decorated with kamon, may be worn as visiting wear (equivalent to a tsukesage or hōmongi).

Mofuku

Mofuku is formal mourning dress for men or women. Both men and women wear kimono of plain black silk with five kamon over white undergarments and white tabi. For women, the obi and all accessories are also black. Men wear a subdued obi and black and white or black and gray striped hakama with black or white zori.

The completely black mourning ensemble is usually reserved for family and others who are close to the deceased.

Tomesode

Irotomesode

Irotomesode (色留袖) are single-color kimono, patterned only below the waistline. Irotomesode with five family crests are the same as formal as kurotomesode, and are worn by married and unmarried women, usually close relatives of the bride and groom at weddings and a medal ceremony at the royal court. An irotomesode may have three or one kamon. Those use as a semi-formal kimono at a party and conferment.

Kurotomesode

Kurotomesode (黒留袖) is a black kimono patterned only below the waistline. They are the most formal kimono for married women. They are often worn by the mothers of the bride and groom at weddings. Kurotomesode usually have five kamon printed on the sleeves, chest and back of the kimono.

Tsukesage

Tsukesage (付け下げ) has more modest patterns that cover a smaller area—mainly below the waist—than the more formal hōmongi. They may also be worn by married women. The differences from homongi is the size of the pattern, seam connection, and not same clothes at inside and outside at hakke As demitoilet, not used in important occasion, but light patterned homongi is more highly rated than classic patterned tsukesage. General tsukesage is often used for parties, not ceremonies.

Uchikake

Uchikake (打掛) is a highly formal kimono worn only by a bride or at a stage performance. The uchikake is often heavily brocaded and is supposed to be worn outside the actual kimono and obi, as a sort of coat. One therefore never ties the obi around the uchikake. It is supposed to trail along the floor, this is also why it is heavily padded along the hem. The uchikake of the bridal costume is either white or very colorful often with red as the base colour.

Susohiki / Hikizuri

The susohiki is usually worn by geisha or by stage performers of the traditional Japanese dance. It is quite long, compared to regular kimono, because the skirt is supposed to trail along the floor. Susohiki literally means "trail the skirt". Where a normal kimono for women is normally 1.5–1.6 m (4.9–5.2 ft) long, a susohiki can be up to 2 m (6.6 ft) long. This is also why geisha and maiko lift their kimono skirt when walking outside, also to show their beautiful underkimono or "nagajuban" (see below).[19]

Jūnihitoe

Jūnihitoe (十二単) is an extremely elegant and highly complex kimono that was only worn by Japanese court-ladies. The jūnihitoe consist of various layers which are silk garments, with the innermost garment being made of white silk. The total weight of the jūnihitoe could add up to 20 kilograms. An important accessory was an elaborate fan, which could be tied together by a rope when folded. Today, the jūnihitoe can only be seen in museums, movies, costume demonstrations, tourist attractions or at certain festivals. These robes are one of the most expensive items of Japanese clothing. Only the Imperial Household still officially uses them at some important functions.

Men's kimono

In contrast to women's kimono, men's kimono outfits are far simpler, typically consisting of five pieces, not including footwear.

Men's kimono sleeves are attached to the body of the kimono with no more than a few inches unattached at the bottom, unlike the women's style of very deep sleeves mostly unattached from the body of the kimono. Men's sleeves are less deep than women's kimono sleeves to accommodate the obi around the waist beneath them, whereas on a woman's kimono, the long, unattached bottom of the sleeve can hang over the obi without getting in the way.

In the modern era, the principal distinctions between men's kimono are in the fabric. The typical men's kimono is a subdued, dark color; black, dark blues, greens, and browns are common. Fabrics are usually matte. Some have a subtle pattern, and textured fabrics are common in more casual kimono. More casual kimono may be made in slightly brighter colors, such as lighter purples, greens and blues. Sumo wrestlers have occasionally been known to wear quite bright colors such as fuchsia.

The most formal style of kimono is plain black silk with five kamon on the chest, shoulders and back. Slightly less formal is the three-kamon kimono.

Accessories and related garments

- Datejime (伊達締め) or datemaki (伊達巻き)

- A wide undersash used to tie the nagajuban and the outer kimono and hold them in place.

- Eri-sugata (衿姿)

- A detached collar that can be worn instead of a nagajuban in summer, when it can be too hot to comfortably wear a nagajuban. It replaces the nagajuban collar in supporting the kimono's collar.

- Fundoshi (褌)

- The traditional Japanese undergarment (G-string codpiece) for adult males, made by a length of cotton.

- Geta (下駄)

- Wooden sandals worn by men and women with yukata. One unique style is worn solely by geisha.

- Hakama (袴)

- A divided (umanoribakama) or undivided skirt (andonbakama) which resembles a wide pair of trousers, traditionally worn by men but contemporarily also by women in less formal situations. A hakama typically is pleated and fastened by ribbons, tied around the waist over the obi. Men's hakama also have a koshi ita, which is a stiff or padded part in the lower back of the wearer. Hakama are worn in several budo arts such as aikido, kendo, iaidō and naginata. Hakama are often worn by women at college graduation ceremonies, and by Miko on shinto shrines. Depending on the pattern and material, hakama can range from very formal to visiting wear.

- Hanten (袢纏)

- The worker's version of the more formal haori. Often padded for warmth, as opposed to the somewhat lighter happi.

- Haori (羽織)

- A hip- or thigh-length kimono-like jacket, which adds formality to an outfit. Haori were originally worn only by men, until it became a fashion for women in the Meiji period. They are now worn by both men and women. . The jinbaori (陣羽織) was specifically made for armoured samurai to wear.

- Haori-himo (羽織紐)

- A tasseled, woven string fastener for haori. The most formal color is white.

- Happi (法被)

- A type of haori traditionally worn by shop keepers and is now associated mostly with festivals.

- Hiyoku (ひよく)

- A type of under-kimono, historically worn by women beneath the kimono. Today they are only worn on formal occasions such as weddings and other important social events. High class kimonos may have extra layers of lining to emulate the appearance of hiyoku worn beneath.

- Juban (襦袢) and Hadajuban (肌襦袢)

- A thin garment similar to an undershirt. It is worn under the nagajuban.[20][21]

- Jittoku (十徳)

- Sometimes called a jittoku haori, is a type of haori worn only by men. Jittoku are only made of unlined ro or sha silk gauze regardless of the season. It falls to the hip, and has sewn himo made of the same fabric as the main garment. While a haori has a small sleeve opening like that of a kimono, a jittoku is fully open at the wrist side. Jittoku do not have mon. Jittoku originated in the Kamakura period (1185-1333 CE), and by the Edo period (1603-1868) they were worn with kimono by male doctors, monks, Confucian scholars and tea ceremony masters as kinagashi (as a replacement for hakama). In the modern day they are worn as kinagashi mainly by male practitioners of tea ceremony who have achieved a sufficiently high rank.

- Nagajuban (長襦袢)

- A kimono-shaped robe worn by both men and women beneath the main outer garment.[22] Since silk kimono are delicate and difficult to clean, the nagajuban helps to keep the outer kimono clean by preventing contact with the wearer's skin. Only the collar edge of the nagajuban shows from beneath the outer kimono.[23] Many nagajuban have removable collars, to allow them to be changed to match the outer garment, and to be easily washed without washing the entire garment. While the most formal type of nagajuban are white, they are often as beautifully ornate and patterned as the outer kimono. Since men's kimono are usually fairly subdued in pattern and color, the nagajuban allows for discreetly wearing very striking designs and colors.[24]

- Kanzashi (簪)

- Hair ornaments worn by women. Many different styles exist, including silk flowers, wooden combs, and jade hairpins.

- Kimono slip (着物スリップ kimono surippu)

- [25] The susoyoke and hadajuban combined into a one-piece garment.[26][27]

- Koshihimo (腰紐)

- A narrow sash used to aid in dressing up, often made of silk or wool. They are used to hold virtually anything in place during the process of dressing up, and can be used in many ways depending on what is worn. Some of the karihimos are removed after datejime or obi have been tied, while others remain worn beneath the layers of the dress. The karihimo that is worn around the hips to create the extra fold or ohashori in women's kimono is called koshihimo, literally "hip ribbon".

- Netsuke (根付, 根付け)

- An ornament worn suspended from the men's obi.

- Obi (帯)

- The tie belt worn with kimono.

- Obi-age (帯揚げ)

- The scarf-like sash which is knotted and tied above the obi and tucked into the top of the obi. Worn with the more formal varieties of kimono.

- Samue (作務衣)

- The everyday clothes for a male Zen Buddhist monk, and the favoured garment for shakuhachi players.

- Susoyoke (裾除け)

- A thin half-slip-like piece of underwear worn by women under the nagajuban.[20][28]

- Tabi (足袋)

- Ankle-high, divided-toe socks usually worn with zōri or geta. There also exist sturdier, boot-like jikatabi, which are used for example to fieldwork.

- Waraji (草鞋)

- Straw rope sandals which are mostly worn by monks.

- Yukata (浴衣)

- An unlined kimono-like garment for summer use, usually made of cotton, linen, or hemp. Yukata are strictly informal, most often worn to outdoor festivals, by men and women of all ages. They are also worn at onsen (hot spring) resorts, where they are often provided for the guests in the resort's own pattern.

- Zōri (草履)

- Traditional sandals worn by both men and women, similar in design to flip-flops. Their formality ranges from strictly informal to fully formal. They are made of many materials, including cloth, leather, vinyl and woven grass, and can be highly decorated or very simple.

Layering

In modern-day Japan the meanings of the layering of kimono and hiyoku are usually forgotten. Only maiko and geisha now use this layering technique for dances and subtle erotic suggestion, usually emphasising the back of the neck. Modern Japanese brides may also wear a traditional Shinto bridal kimono which is worn with a hiyoku.

Traditionally kimonos were worn with hiyoku or floating linings. Hiyoku can be a second kimono worn beneath the first and give the traditional layered look to the kimono. Often in modern kimonos the hiyoku is simply the name for the double-sided lower half of the kimono which may be exposed to other eyes depending on how the kimono is worn.

Old-fashioned kimono styles meant that hiyoku were entire under-kimono, however modern day layers are usually only partial, to give the impression of layering.

Care

In the past, a kimono would often be entirely taken apart for washing, and then re-sewn for wearing.[5] This traditional washing method is called arai hari. Because the stitches must be taken out for washing, traditional kimono need to be hand sewn. Arai hari is very expensive and difficult and is one of the causes of the declining popularity of kimono. Modern fabrics and cleaning methods have been developed that eliminate this need, although the traditional washing of kimono is still practiced, especially for high-end garments.

New, custom-made kimono are generally delivered to a customer with long, loose basting stitches placed around the outside edges. These stitches are called shitsuke ito. They are sometimes replaced for storage. They help to prevent bunching, folding and wrinkling, and keep the kimono's layers in alignment.

Like many other traditional Japanese garments, there are specific ways to fold kimono. These methods help to preserve the garment and to keep it from creasing when stored. Kimonos are often stored wrapped in paper called tatōshi.

Kimono need to be aired out at least seasonally and before and after each time they are worn. Many people prefer to have their kimono dry cleaned. Although this can be extremely expensive, it is generally less expensive than arai hari but may be impossible for certain fabrics or dyes.

References

- ↑ "Kimono". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ "''kimono'' from". Merriam-Webster. 2010-08-13. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ↑ "Kimono | Define Kimono at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ Hanami Web - Inside Japan. All rights reserved. "What Kimono Signifies". HanamiWeb. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Dalby, Liza (2001). Kimono: Fashioning Culture. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295981550. OCLC 46793052.

- ↑ Sharnoff, Lora (1993). Grand Sumo. Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0283-X.

- ↑ Jill Liddell (1989). The Story of the Kimono. E.P. Dutton, p. 28. ISBN 978-0525245742

- ↑ Bardo Fassbender、Anne Peters、Simone Peter、Daniel Högger (2012). The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law. Oxford University Press, p. 477. ISBN 978-0198725220

- ↑ 1871(明治5)年11月12日太政官布告399号

- ↑ Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Old Tokyo: Shirokiya Department Store Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 更新日:2010年11月25日. "戦時衣生活簡素化実施要綱". Ndl.go.jp. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ↑ "国民服令". Geocities.jp. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ↑ "国民服制式特例". Geocities.jp. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ↑ Ruddick, Graham (12 August 2014). "Rise of the kimono, the Japanese fashion taking Britain by storm". The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ Butler, Sarah; Moulds, Josephine; Cochrane, Lauren (12 August 2014). "Kimonos on a roll as high street sees broad appeal of Japanese garment". Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ "男のきもの大全". Kimono-taizen.com. 1999-02-22. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ Hindell, Juliet (May 22, 1999). "World: Asia-Pacific Saving the kimono". BBC. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ http://www.ichiroya.com Archived 2007-11-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Yamanaka, Norio (1982). The Book of Kimono. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International, p. 60. ISBN 0-87011-500-6 (USA), ISBN 4-7700-0986-0 (Japan).

- ↑ Underwear (Hadagi): Hada-Juban. KIDORAKU Japan. Accessed 22 October 2009.

- ↑ Yamanaka, Norio (1982). The Book of Kimono. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International, p. 61. ISBN 0-87011-500-6 (USA), ISBN 4-7700-0986-0 (Japan).

- ↑ Nagajuban undergarment for Japanese kimono

- ↑ Imperatore, Cheryl, & MacLardy, Paul (2001). Kimono Vanishing Tradition: Japanese Textiles of the 20th Century. Atglen, Penn.: Schiffer Publishing. Chap. 3 "Nagajuban—Undergarments", pp. 32–46. ISBN 0-7643-1228-6. OCLC 44868854.

- ↑ A search for "着物スリップ". Rakuten. Accessed 22 October 2009.

- ↑ Yamanaka, Norio (1982). The Book of Kimono. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International, p. 76. ISBN 0-87011-500-6 (USA), ISBN 4-7700-0986-0 (Japan).

- ↑ Underwear (Hadagi): Kimono Slip. KIDORAKU Japan. Accessed 22 October 2009.

- ↑ Underwear (Hadagi): Susoyoke. KIDORAKU Japan. Accessed 22 October 2009.

Further reading

- Milenovich, Sophie (2007). Kimonos. New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-9450-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to kimono. |

| Look up kimono in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kimono buying guide. |

- The Canadian Museum of Civilization - Landscape Kimonos of Itchiku Kubota

- Tokyo National Museum Look for "textiles" under "decorative arts".

- Kyoto National Museum: Textiles

- The Costume Museum: Costume History in Japan

- Kimono Fraise; includes directions on how to put on a kimono

- Immortal Geisha Forums; Comprehensive Resource on Vintage and Modern Kimono Culture

- Love Kimono!; A lot of knowledge of kimono with pictures.

Craft materials

- "Kimono from the V&A Collection". Asia. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- "Fashioning Kimono: Dress in early 20th century Japan". Asia. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-05-13. Retrieved 2007-06-16.