Beta-galactosidase

| β-galactosidase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.png) β-galactosidase from Penicillum sp. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 3.2.1.23 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9031-11-2 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / EGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| galactosidase, beta 1 | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | GLB1 |

| Alt. symbols | ELNR1 |

| Entrez | 2720 |

| HUGO | 4298 |

| OMIM | 230500 |

| RefSeq | NM_000404 |

| UniProt | P16278 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 3 p22.3 |

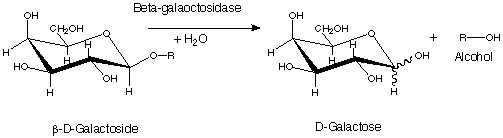

β-galactosidase, also called lactase, beta-gal or β-gal, is a glycoside hydrolase enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of β-galactosides into monosaccharides through the breaking of a glycosidic bond. β-galactosides include carbohydrates containing galactose where the glycosidic bond lies above the galactose molecule. Substrates of different β-galactosidases include ganglioside GM1, lactosylceramides, lactose, and various glycoproteins.[1]

Properties and functions

β-galactosidase is an exoglycosidase which hydrolyzes the β-glycosidic bond formed between a galactose and its organic moiety. It may also cleave fucosides and arabinosides but with much lower efficiency. It is an essential enzyme in the human body. Deficiencies in the protein can result in galactosialidosis or Morquio B syndrome. In E. coli, the lacZ gene is the structural gene for β-galactosidase; which is present as part of the inducible system lac operon which is activated in the presence of lactose when glucose level is low. β-galactosidase synthesis stops when glucose levels are sufficient.[2]

Beta-galactosidase has many homologues based on similar sequences. A few are evolved beta-galactosidase (EBG), beta-glucosidase, 6-phospho-beta-galactosidase, beta-mannosidase, and lactase-phlorizin hydrolase. Although they may be structurally similar, they all have different functions.[3] Beta-gal is inhibited by L-ribose, non-competitive inhibitor iodine, and competitive inhibitors phenylthyl thio-beta-D-galactoside (PETG), D-galactonolactone, isopropyl thio-beta-D-galactoside (IPTG), and galactose.[4]

β-galactosidase is important for organisms as it is a key provider in the production of energy and a source of carbons through the break down of lactose to galactose and glucose. It is also important for the lactose intolerant community as it is responsible for making lactose-free milk and other dairy products. Many adult humans lack the lactase enzyme, which has the same function of beta-gal, so they are not able to properly digest dairy products. Beta-galactose is used in such dairy products as yogurt, sour cream, and some cheeses which are treated with the enzyme to break down any lactose before human consumption. In recent years, beta-galactosidase has been researched as a potential treatment for lactose intolerance through gene replacement therapy where it could be placed into the human DNA so individuals can break down lactose on their own.[5][6]

Structure

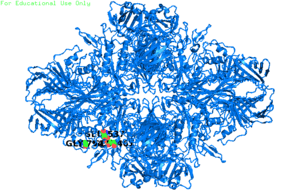

The 1,024 amino acids of E. coli β-galactosidase were first sequenced in 1970,[7] and its structure determined twenty-four years later in 1994. The protein is a 464-kDa homotetramer with 2,2,2-point symmetry.[8] Each unit of β-galactosidase consists of five domains; domain 1 is a jelly-roll type barrel, domain 2 and 4 are fibronectin type III-like barrels, domain 5 a β-sandwich, while the central domain 3 is a TIM-type barrel.

The third domain contains the active site.[9] The active site is made up of elements from two subunits of the tetramer, and disassociation of the tetramer into dimers removes critical elements of the active site. The amino-terminal sequence of β-galactosidase, the α-peptide involved in α-complementation, participates in a subunit interface. Its residues 22-31 help to stabilize a four-helix bundle which forms the major part of that interface, and residue 13 and 15 also contributing to the activating interface. These structural features provide a rationale for the phenomenon of α-complementation, where the deletion of the amino-terminal segment results in the formation of an inactive dimer.

Reaction

β-galactosidase can catalyze two different reactions in organisms. In one, it can go through a process called transgalactosylation to make allolactose, creating a positive feedback loop for the production of β-gal. It can also hydrolyze lactose into galactose and glucose which will proceed into glycolysis.[10] The active site of β-galactosidase catalyzes the hydrolysis of its disaccharide substrate via "shallow" (nonproductive site) and "deep" (productive site) binding. Galactosides such as PETG and IPTG will bind in the shallow site when the enzyme is in "open" conformation while transition state analogs such as L-ribose and D-galactonolactone will bind in the deep site when the conformation is "closed".[4]

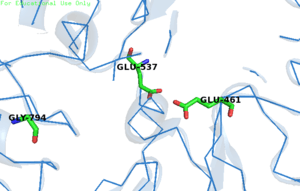

The enzymatic reaction consists of two chemical steps, galactosylation (k2) and degalactosylation (k3). Galactosylation is the first chemical step in the reaction where Glu461 donates a proton to a glycosidic oxygen, resulting in galactose covalently bonding with Glu537. In the second step, degalactosylation, the covalent bond is broken when Glu461 accepts a proton, replacing the galactose with water. Two transition states occur in the deep site of the enzyme during the reaction, once after each step. When water participates in the reaction, galactose is formed, otherwise, when D-glucose acts as the acceptor in the second step, transgalactosylation occurs .[4] It has been kinetically measured that single tetramers of the protein catalyze reactions at a rate of 38,500 ± 900 reactions per minute.[10] Monovalent potassium ions (K+) as well as divalent magnesium ions (Mg2+) are required for the enzyme's optimal activity. The beta-linkage of the substrate is cleaved by a terminal carboxyl group on the side chain of a glutamic acid.

In E. coli, Glu-461 was thought to be the nucleophile in the substitution reaction.[11] However, it is now known that Glu-461 is an acid catalyst. Instead, Glu-537 is the actual nucleophile,[12] binding to a galactosyl intermediate. In humans, the nucleophile of the hydrolysis reaction is Glu-268.[13] Gly794 is important for β-gal activity. It is responsible for putting the enzyme in a "closed", ligand bounded, conformation or "open" conformation, acting like a "hinge" for the active site loop. The different conformations ensure that only preferential binding occurs in the active site. In the presence of a slow substrate, Gly794 activity increased as well as an increase in galactosylation and decrease in degalactosylation.[4]

Uses

The β-galactosidase assay is used frequently in genetics, molecular biology, and other life sciences.[14] An active enzyme may be detected using X-gal, which forms an intense blue product after cleavage by β-galactosidase, and is easy to identify and quantify. It is used for example in blue white screen.[15] Its production may be induced by a non-hydrolyzable analog of allolactose, IPTG, which binds and releases the lac repressor from the lac operator, thereby allowing the initiation of transcription to proceed.

It is commonly used in molecular biology as a reporter marker to monitor gene expression. It also exhibits a phenomenon called α-complementation which forms the basis for the blue/white screening of recombinant clones. This enzyme can be split in two peptides, LacZα and LacZΩ, neither of which is active by itself but when both are present together, spontaneously reassemble into a functional enzyme. This property is exploited in many cloning vectors where the presence of the lacZα gene in a plasmid can complement in trans another mutant gene encoding the LacZΩ in specific laboratory strains of E. coli. However, when DNA fragments are inserted in the vector, the production of LacZα is disrupted, the cells therefore show no β-galactosidase activity. The presence or absence of an active β-galactosidase may be detected by X-gal, which produces a characteristic blue dye when cleaved by β-galactosidase, thereby providing an easy means of distinguishing the presence or absence of cloned product in a plasmid. In studies of leukaemia chromosomal translocations, Dobson and colleagues used a fusion protein of LacZ in mice,[16] exploiting β-galactosidase's tendency to oligomerise to suggest a potential role for oligomericity in MLL fusion protein function.[17]

In 1995, Dimri et al. proposed a new isoform for beta-galactosidase with optimum activity at pH 6.0 (Senescence Associated beta-gal or SA-beta-gal)[18] which would be specifically expressed in senescence (the irreversible growth arrest of cells). Specific quantitative assays were even developed for its detection.[19][20][21] However, it is now known that this is due to an overexpression and accumulation of the lysosomal endogenous beta-galactosidase,[22] and its expression is not required for senescence. Nevertheless, it remains the most widely used biomarker for senescent and aging cells, because it is reliable and easy to detect.

Evolved beta-galactosidase

Some species of bacteria, including E. coli, have additional β-galactosidase genes. A second gene, called evolved β-galactosidase (ebgA) gene was discovered when strains with the lacZ gene deleted (but still containing the gene for galactoside permease, lacY), were plated on medium containing lactose (or other 3-galactosides) as sole carbon source. After a time, certain colonies began to grow. However, the EbgA protein is an ineffective lactase and does not allow growth on lactose. Two classes of single point mutations dramatically improve the activity of ebg enzyme toward lactose.[23][24] and, as a result, the mutant enzyme is able to replace the lacZ β-galactosidase.[25] EbgA and LacZ are 50% identical on the DNA level and 33% identical on the amino acid level.[26] The active ebg enzyme is an aggregate of ebgA -gene and ebgC-gene products in a 1:1 ratio with the active form of ebg enzymes being an α4 β4 hetero-octamer.[27]

References

- ↑ Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- ↑ Garrett, Reginald (2013). Biochemistry. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 1001. ISBN 978-1133106296.

- ↑ "Glycoside hydrolase, family 1, beta-glucosidase (IPR017736) < InterPro < EMBL-EBI". www.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Juers, Douglas H.; Hakda, Shamina; Matthews, Brian W.; Huber, Reuben E. (2003-11-01). "Structural Basis for the Altered Activity of Gly794 Variants of Escherichia coli β-Galactosidase†". Biochemistry. 42 (46): 13505–13511. ISSN 0006-2960. PMID 14621996. doi:10.1021/bi035506j.

- ↑ Salehi, Siamak; Eckley, Lorna; Sawyer, Greta J.; Zhang, Xiaohong; Dong, Xuebin; Freund, Jean-Noel; Fabre, John W. (2009-01-01). "Intestinal lactase as an autologous beta-galactosidase reporter gene for in vivo gene expression studies". Human Gene Therapy. 20 (1): 21–30. ISSN 1557-7422. PMID 20377368. doi:10.1089/hum.2008.101.

- ↑ Ishikawa, Kazuhiko; Kataoka, Misumi; Yanamoto, Toshiaki; Nakabayashi, Makoto; Watanabe, Masahiro; Ishihara, Satoru; Yamaguchi, Shotaro (2015-07-01). "Crystal structure of β-galactosidase from Bacillus circulans ATCC 31382 (BgaD) and the construction of the thermophilic mutants". FEBS Journal. 282 (13): 2540–2552. ISSN 1742-4658. doi:10.1111/febs.13298.

- ↑ Fowler AV, Zabin I (October 1970). "The amino acid sequence of beta galactosidase. I. Isolation and composition of tryptic peptides". J. Biol. Chem. 245 (19): 5032–41. PMID 4918568.

- ↑ Jacobson, R. H.; Zhang, X. -J.; Dubose, R. F.; Matthews, B. W. (1994). "Three-dimensional structure of β-galactosidase from E. Coli". Nature. 369 (6483): 761–766. PMID 8008071. doi:10.1038/369761a0.

- ↑ Matthews BW (June 2005). "The structure of E. coli beta-galactosidase". C. R. Biol. 328 (6): 549–56. PMID 15950161. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2005.03.006.

- 1 2 Juers, Douglas H.; Matthews, Brian W.; Huber, Reuben E. (2012-12-01). "LacZ β-galactosidase: Structure and function of an enzyme of historical and molecular biological importance". Protein Science. 21 (12): 1792–1807. ISSN 1469-896X. PMC 3575911

. PMID 23011886. doi:10.1002/pro.2165.

. PMID 23011886. doi:10.1002/pro.2165. - ↑ Gebler JC, Aebersold R, Withers SG (June 1992). "Glu-537, not Glu-461, is the nucleophile in the active site of (lac Z) beta-galactosidase from Escherichia coli". J. Biol. Chem. 267 (16): 11126–30. PMID 1350782.

- ↑ Yuan J, Martinez-Bilbao M, Huber RE (April 1994). "Substitutions for Glu-537 of beta-galactosidase from Escherichia coli cause large decreases in catalytic activity". Biochem. J. 299 (Pt 2): 527–31. PMC 1138303

. PMID 7909660.

. PMID 7909660. - ↑ McCarter JD, Burgoyne DL, Miao S, Zhang S, Callahan JW, Withers SG (January 1997). "Identification of Glu-268 as the catalytic nucleophile of human lysosomal beta-galactosidase precursor by mass spectrometry". J. Biol. Chem. 272 (1): 396–400. PMID 8995274. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.1.396.

- ↑ Alexander J. Ninfa, Alexander J. (2009). Fundamental Laboratory Approaches for Biochemistry and Biotechnology. ISBN 978-0-470-47131-9.

- ↑ Beta-Galactosidase Assay (A better Miller) - OpenWetWare

- ↑ Dobson, C. L.; Warren, A. J.; Pannell, R.; Forster, A.; Rabbitts, T. H. (2000). "Tumorigenesis in mice with a fusion of the leukaemia oncogene Mll and the bacterial lacZ gene". EMBO J. 19: 843–851. PMC 305624

. PMID 10698926. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.5.843.

. PMID 10698926. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.5.843. - ↑ Krivtsov, A. V.; Armstrong, S. A. (2007). "MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development". Nature Reviews Cancer. 7 (11): 823–833. PMID 17957188. doi:10.1038/nrc2253.

- ↑ Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O (September 1995). "A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (20): 9363–7. PMC 40985

. PMID 7568133. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363.

. PMID 7568133. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. - ↑ Bassaneze V, Miyakawa AA, Krieger JE (January 2008). "A quantitative chemiluminescent method for studying replicative and stress-induced premature senescence in cell cultures". Anal. Biochem. 372 (2): 198–203. PMID 17920029. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2007.08.016.

- ↑ Gary RK, Kindell SM (August 2005). "Quantitative assay of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity in mammalian cell extracts". Anal. Biochem. 343 (2): 329–34. PMID 16004951. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2005.06.003.

- ↑ Itahana K, Campisi J, Dimri GP (2007). "Methods to detect biomarkers of cellular senescence: the senescence-associated beta-galactosidase assay". Methods Mol. Biol. Methods in Molecular Biology. 371: 21–31. ISBN 978-1-58829-658-0. PMID 17634571. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-361-5_3.

- ↑ Lee BY, Han JA, Im JS, Morrone A, Johung K, Goodwin EC, Kleijer WJ, DiMaio D, Hwang ES (April 2006). "Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase is lysosomal beta-galactosidase". Aging Cell. 5 (2): 187–95. PMID 16626397. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00199.x.

- ↑ Hall, B. G. (1977). "Number of mutations required to evolve a new lactase function in Escherichia coli". Journal of Bacteriology. 129 (1): 540–3. PMC 234956

. PMID 318653.

. PMID 318653. - ↑ Hall, B. G. (1981). "Changes in the substrate specificities of an enzyme during directed evolution of new functions". Biochemistry. 20 (14): 4042–9. PMID 6793063. doi:10.1021/bi00517a015.

- ↑ Hall, B. G. (1976). "Experimental evolution of a new enzymatic function. Kinetic analysis of the ancestral (ebg) and evolved (ebg) enzymes". Journal of Molecular Biology. 107 (1): 71–84. PMID 794482. doi:10.1016/s0022-2836(76)80018-6.

- ↑ Stokes, H. W.; Betts, P. W.; Hall, B. G. (1985). "Sequence of the ebgA gene of Escherichia coli: Comparison with the lacZ gene". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2 (6): 469–77. PMID 3939707.

- ↑ Elliott, A. C.; k, S; Sinnott, M. L.; Smith, P. J.; Bommuswamy, J; Guo, Z; Hall, B. G.; Zhang, Y (1992). "The catalytic consequences of experimental evolution. Studies on the subunit structure of the second (ebg) beta-galactosidase of Escherichia coli, and on catalysis by ebgab, an experimental evolvant containing two amino acid substitutions". The Biochemical Journal. 282 (1): 155–64. PMC 1130902

. PMID 1540130. doi:10.1042/bj2820155.

. PMID 1540130. doi:10.1042/bj2820155.

External links

- beta-Galactosidase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)