Cedilla

| ̧ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cedilla | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A̧ | a̧ |

| B̧ | b̧ |

| Ç | ç |

| Ḉ | ḉ |

| Ç̇ | ç̇ |

| Ḑ | ḑ |

| Ȩ | ȩ |

| Ȩ̇ | ȩ̇ |

| Ḝ | ḝ |

| Ə̧ | ə̧ |

| Ɛ̧ | ɛ̧ |

| Ģ | ģ |

| Ḩ | ḩ |

| I̧ | i̧ |

| Ɨ̧ | ɨ̧ |

| Ķ | ķ |

| Ļ | ļ |

| M̧ | m̧ |

| Ņ | ņ |

| O̧ | o̧ |

| Ɔ̧ | ɔ̧ |

| Q̧ | q̧ |

| Ŗ | ŗ |

| Ş | ş |

| ſ̧ | ß̧ |

| Ţ | ţ |

| U̧ | u̧ |

| X̧ | x̧ |

| Z̧ | z̧ |

A cedilla (/sᵻˈdɪlə/ si-DIL-ə; from Spanish), also known as cedilha (from Portuguese) or cédille (from French), is a hook or tail ( ¸ ) added under certain letters as a diacritical mark to modify their pronunciation. In Catalan, French, and Portuguese, it is used only under the c, and the entire letter is called respectively c trencada (i.e. "broken C"), c cédille, and c cedilhado (or c de cedilha, colloquially).

Origin

The tail originated in Spain as the bottom half of a miniature cursive z. The word "cedilla" is the diminutive of the Old Spanish name for this letter, ceda (zeta).[1] Modern Spanish, however, no longer uses this diacritic, although it is used in Portuguese,[2] Catalan, Occitan, and French, which gives English the alternative spellings of cedille, from French “cédille”, and the Portuguese form cedilha. An obsolete spelling of cedilla is cerilla.[2] The earliest use in English cited by the Oxford English Dictionary[2] is a 1599 Spanish-English dictionary and grammar.[3] Chambers’ Cyclopædia[4] is cited for the printer-trade variant ceceril in use in 1738.[2] The main use in English is not universal and applies to loan words from French and Portuguese such as "façade", "limaçon" and "cachaça" (often typed "facade", "limacon" and "cachaca" because of lack of ç keys on Anglophone keyboards).

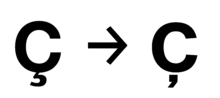

With the advent of modernism, the calligraphic nature of the cedilla was thought somewhat jarring on sans-serif typefaces, and so some designers instead substituted a comma design, which could be made bolder and more compatible with the style of the text.[lower-alpha 1] This can add to confusion as the use of commas as opposed to cedillas varies by language.

C

The most frequent character with cedilla is "ç" ("c" with cedilla, as in façade). It was first used for the sound of the voiceless alveolar affricate /ts/ in old Spanish and stems from the Visigothic form of the letter "z" (ꝣ), whose upper loop was lengthened and reinterpreted as a "c", whereas its lower loop became the diminished appendage, the cedilla.

It represents the "soft" sound /s/, the voiceless alveolar sibilant, where a "c" would normally represent the "hard" sound /k/ (before "a", "o", "u", or at the end of a word) in English and in certain Romance languages such as Catalan, Galician, French (where ç appears in the name of the language itself, français), Ligurian, Occitan, and Portuguese. In Occitan, Friulian and Catalan ç can also be found at the beginning of a word (Çubran, ço) or at the end (braç).

It represents the voiceless postalveolar affricate /tʃ/ (as in English "church") in Albanian, Azerbaijani, Crimean Tatar, Friulian, Kurdish, Tatar, Turkish (as in çiçek, çam, çekirdek, Çorum), and Turkmen. It is also sometimes used this way in Manx, to distinguish it from the velar fricative.

In the International Phonetic Alphabet, ⟨ç⟩ represents the voiceless palatal fricative.

S

The character "ş" represents the voiceless postalveolar fricative /ʃ/ (as in "show") in several languages, including many belonging to the Turkic languages, and included as a separate letter in their alphabets:

- Turkish

- For example, it is used in Turkish words and names like Eskişehir, Şımarık, Hasan Şaş, Rüştü Reçber etc.

- Azerbaijani

- Crimean Tatar

- Gagauz

- Tatar

- Turkmen

- Romanian (substitution use when S-comma [Ș] was missing from pre-3.0 Unicode standards, and older standards, still frequent, but an error)

- Kurdish

- In HTML character entity references

Şandşcan be used.

Latvian

Comparatively, some consider the diacritics on the Latvian consonants "ģ", "ķ", "ļ", "ņ", and formerly "ŗ" to be cedillas. Although their Adobe glyph names are commas, their names in the Unicode Standard are "g", "k", "l", "n", and "r" with a cedilla. The letters were introduced to the Unicode standard before 1992, and their names cannot be altered. The uppercase equivalent "Ģ" sometimes has a regular cedilla.

Marshallese

Four letters in Marshallese have cedillas: "ļ", "m̧", "ņ" and "o̧". In standard printed text they are always cedillas, and their omission or the substitution of comma below and dot below diacritics are nonstandard.

As of 2011, many font rendering engines do not display any of these properly, for two reasons:

- "ļ" and "ņ" usually do not display properly at all, because of the use of the cedilla in Latvian. Unicode has precombined glyphs for these letters, but most quality fonts display them with comma below diacritics to accommodate the expectations of Latvian orthography. This is considered nonstandard in Marshallese. The use of a zero-width non-joiner between the letter and the diacritic can alleviate this problem: "ļ" and "ņ" may display properly, but may not; see below.

- "m̧" and "o̧" do not currently exist in Unicode as precombined glyphs, and must be encoded as the plain Latin letters "m" and "o" with the combining cedilla diacritic. Most Unicode fonts issued with Windows do not display combining diacritics properly, showing them too far to the right of the letter, as with Tahoma ("m̧" and "o̧") and Times New Roman ("m̧" and "o̧"). This mostly affects "m̧", and may or may not affect "o̧". But some common Unicode fonts like Arial Unicode MS ("m̧" and "o̧"), Cambria ("m̧" and "o̧") and Lucida Sans Unicode ("m̧" and "o̧") do not have this problem. When "m̧" is properly displayed, the cedilla is either underneath the center of the letter, or is underneath the right-most leg of the letter, but is always directly underneath the letter wherever it is positioned.

Because of these font display issues, it is not uncommon to find nonstandard ad hoc substitutes for these letters. The online version of the Marshallese-English Dictionary (the only complete Marshallese dictionary in existence) displays the letters with dot below diacritics, all of which do exist as precombined glyphs in Unicode: "ḷ", "ṃ", "ṇ" and "ọ". The first three exist in the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, and "ọ" exists in the Vietnamese alphabet, and both of these systems are supported by the most recent versions of common fonts like Arial, Courier New, Tahoma and Times New Roman. This sidesteps most of the Marshallese text display issues associated with the cedilla, but is still inappropriate for polished standard text.

Other diacritics

Languages such as Romanian add a comma (virgula) to some letters, such as ș, which looks like a cedilla, but is more precisely a diacritical comma. This is particularly confusing with letters which can take either diacritic: for example, the consonant /ʃ/ is written as "ş" in Turkish but "ș" in Romanian, and Romanian writers will sometimes use the former instead of the latter because of insufficient font or character-set support.

The Polish letters "ą" and "ę" and Lithuanian letters "ą", "ę", "į", and "ų" are not made with the cedilla either, but with the unrelated ogonek diacritic.

French

In 1868, Ambroise Firmin-Didot suggested in his book Observations sur l'orthographe, ou ortografie, française (Observations on French Spelling) that French phonetics could be better regularized by adding a cedilla beneath the letter "t" in some words. For example, the suffix -tion this letter is usually not pronounced as (or close to) /t/ in either French or English, but respectively as /sjɔ̃/ and /ʃən/. It has to be distinctly learned that in words such as French diplomatie (but not diplomatique) and English action it is pronounced /s/ and /ʃ/, respectively (but not in active in either language). A similar effect occurs with other prefixes or within words also in French and English, such as partial where t is pronounced /s/ and /ʃ/ respectively. Firmin-Didot surmised that a new character could be added to French orthography. A similar letter, the t-comma, does exist in Romanian, but it has a comma accent, not a cedilla one.

Romanian

The Unicode character for Ţ (T with cedilla) and Ş (S with cedilla) were wrongly implemented in Windows Romanian. In Windows 7, Microsoft corrected the error by replacing T-cedilla with T-comma (Ț) and S-cedilla with S-comma (Ș).

Gagauz

Gagauz uses Ţ (T with cedilla), the only language to do so, and Ş (S with cedilla).

Encodings

Unicode provides precomposed characters for some Latin letters with cedillas. Others can be formed using the cedilla combining character.

| Description | Letter | Unicode | HTML |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cedilla (spacing) | ¸ | U+00B8 | ¸ or ¸ |

| Combining cedilla | ◌̧ | U+0327 | ̧ |

| C with cedilla | Ç ç | U+00C7 U+00E7 | Ç or Ç ç or ç |

| C with cedilla and acute accent | Ḉ ḉ | U+1E08 U+1E09 | Ḉ ḉ |

| Combining small c with cedilla (medieval superscript diacritic)[10] | ◌ᷗ | U+1DD7 | ᷗ |

| D with cedilla | Ḑ ḑ | U+1E10 U+1E11 | Ḑ ḑ |

| E with cedilla | Ȩ ȩ | U+0228 U+0229 | Ȩ ȩ |

| E with cedilla and breve | Ḝ ḝ | U+1E1C U+1E1D | Ḝ ḝ |

| G with cedilla | Ģ ģ | U+0122 U+0123 | Ģ ģ |

| H with cedilla | Ḩ ḩ | U+1E28 U+1E29 | Ḩ ḩ |

| K with cedilla | Ķ ķ | U+0136 U+0137 | Ķ ķ |

| L with cedilla | Ļ ļ | U+013B U+013C | Ļ ļ |

| N with cedilla | Ņ ņ | U+0145 U+0146 | Ņ ņ |

| R with cedilla | Ŗ ŗ | U+0156 U+0157 | Ŗ ŗ |

| S with cedilla | Ş ş | U+015E U+015F | Ş ş |

| T with cedilla | Ţ ţ | U+0162 U+0163 | Ţ ţ |

References

- ↑ For cedilla being the diminutive of ceda, see definition of cedilla, Diccionario de la lengua española, 22nd edition, Real Academia Española (in Spanish), which can be seen in context by accessing the site of the Real Academia and searching for cedilla. (This was accessed 27 July 2006.)

- 1 2 3 4 "cedilla". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Minsheu, John (1599) Percyvall's (R.) Dictionarie in Spanish and English (as enlarged by J. Minsheu) Edm. Bollifant, London, OCLC 3497853

- ↑ Chambers, Ephraim (1738) Cyclopædia; or, an universal dictionary of arts and sciences (2nd ed.) OCLC 221356381

- ↑ Jacquerye, Denis Moyogo. "Cedilla Comma" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "Neue Haas Grotesk". The Font Bureau, Inc. p. Introduction.

- ↑ "Neue Haas Grotesk - Font News". Linotype.com. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "Schwartzco Inc". Christianschwartz.com. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "Akzidenz Grotesk Buch". Berthold/Monotype. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "N3027: Proposal to add medievalist characters to the UCS" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. 2006-01-30.

External links

- ScriptSource — Positioning the traditional cedilla

- Diacritics Project—All you need to design a font with correct accents

- Keyboard Help—Learn how to make world language accent marks and other diacriticals on a computer