South African Republic

| South African Republic | ||||||

| Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (Dutch) | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Anthem Transvaalse Volkslied | ||||||

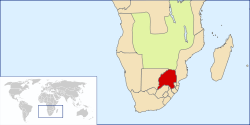

Location of the South African Republic, circa 1890. | ||||||

| Capital | Pretoria | |||||

| Languages | Dutch | |||||

| Religion | Nederduitsch Hervormde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church) | |||||

| Government | Republic | |||||

| President | ||||||

| • | 1857–1863 | Marthinus Wessel Pretorius | ||||

| • | 1883–1902 | Paul Kruger | ||||

| • | 1900–1902 | Schalk Willem Burger (acting) | ||||

| History | ||||||

| • | Established | 17 January 1852 | ||||

| • | First Boer War | 20 December 1881 | ||||

| • | Independence | 27 February 1884 | ||||

| • | Second Boer War | 11 October 1899 | ||||

| • | Treaty of Vereeniging | 31 May 1902 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | 1870[1] | 191,789 km² (74,050 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 1870[1] est. | 120,000 | ||||

| Density | 0.6 /km² (1.6 /sq mi) | |||||

| Currency | Suid-Afrikaanse pond (South African pound) | |||||

| Today part of | | |||||

The South African Republic (Dutch: Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, ZAR), often referred to as the Transvaal and sometimes as the Republic of Transvaal, was an independent and internationally recognised country in Southern Africa from 1852 to 1902. The country defeated the British in what is often referred to as the First Boer War and remained independent until the end of the Second Boer War on 31 May 1902, when it was forced to surrender to the British. The territory of the ZAR became known after this war as the Transvaal Colony. After the outbreak of the First World War a small number of Boers staged the Maritz Rebellion and aligned themselves with the Central Powers in a failed gambit to regain independence.

Name and etymology

Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR)

Constitutionally the name of the country was Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (South African Republic or ZAR). Many people also called the ZAR Transvaal, in reference to the area over (or trans) the Vaal River[2] including the British press and the press in Europe. In fact the name "Transvaal" was later so often used that later the British objected to the use of the real name (The South African Republic). The British pointed out that the Convention of Pretoria of 3 August 1881[3] referred to the 'Transvaal Territory' and that the Transvaal and the South African Republic did not have the same boundaries.[4] However, in the London Convention dated 27 February 1884,[3]:469–474 a subsequent treaty between Britain and the ZAR, Britain acquiesced and reverted to the use of the true name, "The South African Republic".

Transvaal

The name of the South African Republic was of such importance that on 1 September 1900 the British declared by special proclamation that the name of the South African Republic be changed[3]:514 from "South African Republic" to "The Transvaal" and that the entire territory shall henceforth and forever be known as "The Transvaal". This proclamation was issued during the Second Boer War and whilst the ZAR was still an independent country.

On 31 May 1902, the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed, with the South African Government, Orange Free State Government and the British Government which also converted the ZAR into the Transvaal Colony. On 20 May 1903 an Inter Colonial Council[3]:516 was established, to manage the colonies of the British Government. The name "Transvaal" was finally changed in 1994, when the ANC government broke up the Transvaal area and renamed the core, to "Gauteng".

History

Early history

In paleolithic times, between 2.2 to 3.3 million years ago, hominids lived within the geographic area of the ZAR. The earliest hominid bones, between 2.2 to 3.3 million years old, was discovered at Sterkfontein in 1994. In 1938 Paranthropus robustus bones were found at Kromdraai, and during 1947 several more examples of Australopithecus africanus were uncovered in Sterkfontein. The pastoral San People lived on the lands of Southern Africa and they were later joined by Bantu people from North Africa and then Europeans. The Bantu, who displaced the San, were themselves decimated and scattered by the internecine warfare known as the Mfecane which left most of the lands of the ZAR abandoned and vacant. The greater portion of the territory south of the twenty-second parallel of latitude was literally without any inhabitants.[5] With the arrival of the Europeans and their defence of Matabele raids, the Bantu tribes inhabiting the mountains and deserts could settle on open country, make gardens and sleep in safety. The Europeans were masters and owners of the land, but in accordance with the ancient Dutch custom, they permitted each newly settled Bantu community to be governed by its own chief. The Europeans subjected the Bantu community to a kraal tax, which was fully accepted by the Bantu communities and loyally paid while the Europeans provided peace and security, according to historian George McCall Theal.[5]:335

Formation

The Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek came into existence on 17 January 1852[3]:357–359 when the United Kingdom signed the Sand River Convention treaty with about 40,000 Boer people, recognising their independence in the region to the north of the Vaal River. The first president of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek was Marthinus Wessel Pretorius, elected in 1857, son of Boer leader Andries Pretorius, who commanded the Boers to victory at the Battle of Blood River. The capital was established at Potchefstroom and later moved to Pretoria. The parliament was called the Volksraad and had 24 members.

Independence

The South African Republic became fully independent on the 27 February 1884 when the London Convention was signed. The country independently also entered into various agreements with other foreign countries after that date. On 3 November 1884 the country signed a Postal convention with the government of the Cape Colony and later similarly with the Orange Free State.[3]:477

Expansion

On the November 1859[3]:420–422 the independent Republic of Lijdenburg merged with the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek. On 9 May 1887, burghers from the territories of Stellaland and Goosen[3]:479 (sometimes referred to as Goshen) were granted rights to the ZAR franchise. On the 25th of July 1895 the burghers that took part in the battle at Zoutpansberg,[3]:505 were granted citizenship of the ZAR.

Constitution and laws

The constitution of the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek has been referred to as legally interesting for its time.[6] It contained provisions for the division between the political leadership and office bearers in government administration. The legal system consisted of higher and lower courts and had adopted a jury system. The laws were enforced by the South African Republic Police (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek Politie or ZARP) which were divided into Mounted Police (Rijdende Politie) and Foot Police. On 10 April 1902 the Magistrates Court powers were extended to increase the civil ceiling amounts and to expand criminal jurisdiction to include all criminal cases not punishable by death or banishment. Also established was a Municipal Government, Witwatersrand District court and the High Court of Transvaal.[3]:515

Religion

Initially the State and Church were not separated in the constitution of the ZAR, citizens of the ZAR had to be members of the Dutch Reformed Church. In 1858 these clauses were altered in the constitution to allow for the Volksraad to approve other Dutch Christian churches.[3]:358–359 The Reformed Church was approved by the Volksraad in 1858, which had the effect of allowing Paul Kruger, of the Gereformeerde Kerk to remain a citizen of the ZAR. The Bible itself was also often used to interpret the intention of legal documents. The Bible was also used to interpret a prisoner exchange agreement, reached in terms of the Sand River Convention, between a commando of the ZAR, led by Paul Kruger and a Commando of the Orange Free State. President Boshoff had issued a death sentence over two ZAR citizens, for treason. Paul Kruger argued with President Boshoff that the Bible said punishment does not mean a death sentence and at the prisoner exchange, it was agreed that the accused would be punished if found guilty. After double checking Commandant Paul Kruger's Bible, President Boshoff commuted the sentences to lashes with a sjambok.[7]

Citizenship

Citizenship of the ZAR was legislated by the constitution as well as Law no 7 of 1882, as amended on 23 June 1890.[3]:495 Citizenship was gained by being born in the republic or by naturalization. The voting age was 16 years. Persons not born in the Republic (Foreigners) could become citizens by taking the prescribed oath and procuring the letters of naturalization. The oath involved abandoning, discarding and renouncing all allegiance and subjugation towards foreign sovereignties and in particular their previous citizenship. Foreigners had to have been residing in the Republic for a period of two years, be of good character and have been accepted as member of the Dutch Reformed or Reformed Church. On 20 September 1893 the ZAR Constitution was amended so that two thirds of the Volksraad would have to agree to changes to the citizenship law. This proclamation, number 224, also changed Law no 7 with regards to voting.[3]:501 All citizens who was born in the ZAR or who obtained their franchise prior to 23 June 1890 would have the right to vote for both the first and second volksraad and in all other elections. Citizens who obtained their franchise through naturalization after 23 June 1890, would be able to vote in all elections, except those for the first Volksraad.

Racism

The constitution promoted racialism as it treated European (white) people differently from Native (black) people. Although slavery was illegal in the constitution and foreigners (white and black) were both discriminated against, black foreigners had fewer rights than their white counterparts. Black and Asian foreigners could never become citizens of the ZAR, at this time in history, this was very similar to many other European countries as well as in the new world. Discrimination on the basis of race was prevalent in the ZAR and black British subjects were forced to reside in ghettos outside cities with Asian and black races, whilst white races were free to live anywhere. One of the justifications often used by the ZAR Government for its institutional racism was that "sanitation and regard to public health necessitated that measure of segregation".[8]

Language and culture

Language

The language spoken and written by the citizens of the ZAR was high Dutch. This high Dutch was carried over into the Transvaal Colony and later the Union of South Africa. Up to 1925, the high Dutch language was still in use. In fact there were four main languages: High Dutch, Low or South African Dutch (Afrikaans), High Afrikaans, and English.[9] After 1925, High Dutch was removed and only Afrikaans and English remained as official languages. On 3 October 1884 the Volksraad stated that they had reason to believe that in certain schools impure Dutch was being used. The Volksraad issued Proclamation 207 and compelled the Superintendent of Education to apply the language law[10] enforcing the exclusive use of the Dutch Language.[3]:477 On the 30 July 1888 the high Dutch language was declared the only language[3]:481–482 to be used in the country, not only in government but also in schools, trade and general use. All other languages were declared "foreign".[11] These changes to the ZAR laws made the use of all other foreign languages illegal in the ZAR. Use of any foreign language was subject to criminal penalty[3]:483 and fine of 20 ZAR Pond for each offense. The British similarly had declared English to be the only language spoken in the Cape Colony some decades earlier to outlaw[12] the Dutch Language. The discovery of gold in 1885 led to a major influx of foreigners. By 1896 the language of government and citizens remained Dutch but in many market places, shops and homes the English language was spoken.[13]

Boer Wars

War with Mapela and Makapaan, 1854

Hendrik Potgieter was elected at the assembly of 1849 as Commandant General for life and it became necessary, to avoid strife, to appoint three commandants general all possessing equal powers.[7]:41 Commandant General A.W.J. Pretorius became Commandant General of the Potchefstroom and Rustenburg districts. On the 16th of December 1852 Commandant General Potgieter died and his son, Piet Potgieter, was appointed in his stead as Commandant General of the Lydenburg and Zoutpansberg districts of the ZAR. There were some disputes over cattle which Mapela was raising on behalf of Potgieter and earlier Commandant Scholtz had confiscated a large amount of rifles, ammunition, rifle repair equipment and materials of war from the home of English missionary, Reverend Livingstone. Livingstone admitted to storing these for Secheli and by this he was acting in breach of the Sand River Convention of 1852, which prescribed that neither arms nor ammunition should be supplied to the natives.[7]:40 In 1853, the brother of Hendrik Potgieter, Herman Potgieter was called to Mapela to come and cull the elephant population.[7]:42 When Potgieter arrived, Maphela took Potgieter, his son, his groom and a few other burghers to show them where the elephants were. On the way, Mapela and hundreds of natives attacked the Potgieter party. They killed Andries Potgieter, the son of Herman Potgieter and then dragged Potgieter up a hill, where they proceeded to skin him alive. They stopped once they had torn the entrails from his body.[7]:43 At the same time of these events, Makapaan attacked and killed an entire convoy of woman and children traveling to Pretoria. The two chiefs had concluded an agreement to murder all the Europeans in their respective districts[7]:44 and to keep the cattle that they were raising for the Europeans. General Piet Potgieter set out with 100 men from Zoutpansberg and Commandant General Pretorius left Pretoria with 200 men. After the commandos met up, they first attacked Makapaan and the natives were driven back to their caves in the mountains where they lived before. The Boers held them at siege in their caves and eventually hundreds of women and children came out.

Orphan children of the native tribes were "ingeboekt" at "autorisatie voor den landrost" or translated into English, "booked in" strictly controlled by legal process, at appointed Boer families to look after them until they came of age.[7]:47 (The administration was similar to the system of indentured workers, (which was simply another form of slavery) with the exception that children so registered had to be released at age 16) The commando would return all such children to the nearest landrost district, for registration and allocation to a Boer family. As there were slavers and other criminals dealing in children any burgher found in possession of an unregistered minor child was guilty of a criminal offense. These children were also often called "oorlams" in reference to being overly used to the Dutch culture, and in reference to a hand raised orphan sheep, or "hanslam". These children, even after their 16th birthday, and being free to come and go as they please, never re-connected with their own culture and own language and except for surviving and being cared for in terms of food and shelter, were basically forcefully divorced from their native tribe forever.

Among the casualties of this war was Commandant General Potgieter.[7]:46 The natives were armed with rifles and were good shots. The general was killed by native sniper on the ridge of a trench and his body recovered by then commandant Paul Kruger whilst under heavy fire from the natives. What remained of the joint commando, now under command of General Pretorius focussed their attention on Mapela. By the time the commando had reached Mapela, the natives had fled. A few wagons, bloody clothes, chests and other goods were discovered at a kop near Mapela's town. Mapela and his soldiers escaped and with their rifles and ammunition intact and Mapela was only captured much later, in 1858.

Civil War, 1861–1864

Commandant-General Schoeman did not accept the 20 September 1858 proclamation by the Volksraad, where the members of the Christelijk Gereformeerde Church, would be entitled to citizenship of the ZAR. Consequently, Paul Kruger was not accepted as a citizen and disallowed from political intercourse. Acting President van Rensburg called a special meeting of the general council of the Hervormde kerk (Dutch Reformed Church) which then voted in a special resolution to allow members of the Reformed Church access to the franchise.

Sekhukhune War of 1876

In 1876, a war between the ZAR and the Bapedi broke out over cattle theft and land encroachment.[14] The Volksraad declared war on the Pedi leader, Sekhukhune on 16 May 1876. The war only began in July 1876. The president of the ZAR, Burgers led an army of 2000 burghers and was joined by a strong force of Swazi warriors. The Swazis joined the war to aid Mampuru, who was ousted from his position of chieftain by Sekhukhune.[14] One of the early battles occurred at Botsabelo Mission Station on 13 July 1876, against Johannes Dinkwanyane, who was Sekhukhune's brother. The Boer forces were led by Commandant Coetzee and accompanied by Swazi warriors. The Swazi warriors launched a surprise and successful attack while the Boers held back.[14] Seeing this, the Swazis refused to hand over to the Boers any spoils from the battle, thereafter leaving and returning to Swaziland. Dinkwanyane's followers also surrendered after this campaign.[14]

First Boer War, 1880–1881

On 12 April 1877, Britain issued a proclamation called: "ANNEXATION OF THE S.A. REPUBLIC TO THE BRITISH EMPIRE"[3]:448–449 In the proclamation, the British claim that the country is unstable, ungovernable, bankrupt and facing civil war. The unsuccessful annexation did not suspend self-government and attempted to convert the ZAR into a British colony.[3]:448–453

The Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek viewed this proclamation as an act of aggression,[3]:454–455 and resisted. Instead of declaring war, the country decided to send a delegation to United Kingdom and the USA, to protest. This did not have any effect and the First Boer War formally broke out on 20 December 1880. The First Boer War was the first conflict since the American Revolution in which the British had been decisively defeated and forced to sign a peace treaty under unfavourable terms. It would see the introduction of the khaki uniform, marking the beginning of the end of the famous Redcoat. The Battle of Laing's Nek would be the last occasion where a British regiment carried its official regimental colours into battle. The Pretoria Convention of 1881 was signed on 3 August 1881 and ratified on 25 October 1881 by the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek (where the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek is referred to by the name "Transvaal Territory"). The Pretoria Convention of 1881[3]:456–457 was superseded in 1884 by the London Convention,[3]:469–470 and in which the British suzerainty over the South African Republic, was relinquished. The British Government, in the London Convention, accepted the name of the country as The South African Republic. The convention was signed in duplicate, in London on 27 February 1884 by Hercules Robinson, S.JP. Kruger, S.J. Du Toit and N.J. Smit and later ratified by the South African Republic (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) Volksraad.

In 1885 extremely rich gold reefs were discovered in the ZAR. The South African Republic burghers were farmers and not miners and much of the mining fell to immigrants. The immigrants were also referred to as "outlanders" (uitlanders). By 1897 the immigrants had invested over 300 000 000 British Pounds in the ZAR goldfields.

Second Boer War, 1899–1902

Britain first attacked the independent country of South Africa in December 1895, the Jameson Raid. After that failed attack the British started building up massive amounts of troops and resources at the borders of the ZAR. Then they demanded voting rights for the 50,000 British nationals and the 10, 000 other nationals in South Africa, even though none of these nationals were at that time South African citizens. Kruger rejected the British demand and called for the withdrawal of British troops from the ZAR's borders. When the British refused, Kruger declared war against Britain. Britain received assistance from Australia,[16] Canada[17] and New Zealand[18] as well as forces and citizens of colonies like the Colony of Natal and the Cape Colony.

The Second Boer War was a watershed for the British Army in particular and for the British Empire as a whole. The British used concentration camps where women and children were held without adequate food or medical care.[15] The abhorrent conditions in these camps caused the death of 4,177 women and 22,074 children under sixteen; death rates were between 344 and 700 per 1000.[19] There is ![]() Media related to Second Boer War concentration camps at Wikimedia Commons.

Media related to Second Boer War concentration camps at Wikimedia Commons.

The Treaty of Vereeniging was signed on 31 May 1902. The treaty ended the existence of the ZAR and the Orange Free State as independent Boer republics and placed them within the British Empire. The Boers were promised eventual limited self-government, which was granted in 1906 and 1907. The Union of South Africa was established in 1910.

Political structure

Officials

- President of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek

- State Secretary of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek

- State Attorney of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek

Divisions

The country was divided into 17 districts:[13]

- Pretoria district: Pretoria

- Potchefstroom district: Potchefstroom, Ventersdorp, Klerksdorp, Venterskroon, Wolmaranstad

- Rustenburg district: Rustenburg

- Waterberg district: Nylstroom, Hartingsburg

- Zoutpansberg district: Pietersburg, Haenertsburg, Woodbush, Eersteling, Marabastad, Smitsdorp

- Lydenburg district: Lydenburg, Pilgrim's Rest, Barberton, Eureka City, FairView, Moodies, Jamestown

- Middelburg district: Middelburg, Roossenekal

- Heidelberg district: Heidelberg, Johannesburg, Elsburg, Boksburg, Krugersdorp

- Wakkerstroom district: Wakkerstroom, Amersfoort

- Piet Retief district: Piet Retief

- Utrecht district: Utrecht, Luneburg

- Bloemhof district: Christiania, Bloemhof, Schweizer-Reneke

- Marico district: Zeerust, Jacobsdal, Ottoshoop

- Lichtenburg district: Lichtenburg

- Standerton district: Standerton, Bethal

- Ermelo district: Ermelo, Amsterdam, Carolina

- Vryheid district: Vryheid

Flag

The national flag of the ZAR featured three horizontal stripes of red, white, and blue (mirroring the Dutch national flag), with a vertical green stripe at the hoist, and was known as the Vierkleur (lit. four colours). The former national flag of South Africa (from 1927 to 1994) had, as part of a feature contained within its central white bar, a horizontal flag of the Transvaal Republic (ZAR).

See also

References

- 1 2 Alexander Mackay (1870). Manual of modern geography, mathematical, physical, and political. p. 484.

- ↑ Tamarkin (1996). Cecil Rhodes and the Cape Afrikaners. pp. 249–250.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Eybers (1917). Select constitutional documents illustrating South African history 1795–1910. pp. 455–463.

- ↑ Irish University Press Series: British Parliamentary Papers Colonies Africa, (BPPCA Transvaal Vol 37 (1971) No 41 at 267)

- 1 2 THEALE (1894). South Africa - Story of the Nations. pp. 333–334.

- ↑ Entry: South African Law Review1954. Butterworth's South African Law Review, 1954

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kruger, Paul (1902). Memoirs of Paul Kruger. Canada: George R Morang and Co. p. 59.

- ↑ "Origin of the Anglo-Boer War Revealed – C. H. Thomas (originally published in 1899 by Hodder & Stoughton)".

- ↑ Standaard Afrikaans (PDF). Abel Coetzee (Afrikaner Pers). 1948. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

- ↑ (Law number 1, Article 7 of 1882, Locale Wetten der Z.A Rep. I, 1071)

- ↑ (Law articles 1017/1025 dd. 13 Juli 1888 & article 1026/1027, dd. 14 Juli 1888 & article 1030, dd. 16 Juli 1888)

- ↑ Kachru, Braj; Kachru, Yamuna; Nelson, Cecil (2009). The Handbook of World Englishes. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 160–161. ISBN 1405188316.

- 1 2 De Villiers, John (1896). The Transvaal. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 Kinsey, H.W. "THE SEKUKUNI WARS". Military History Journal Vol 2 No 5 - June 1973. Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- 1 2 "HOBHOUSE E - THE BRUNT OF THE WAR - METHUEN & CO (1902)".

- ↑ Australian War Memorial (2008). "Australian Military Statistics". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ↑ Marshall, Robert. "Boer War Remembered". Maclean's.

- ↑ New Zealand History Online (2008). "Brief history – New Zealand in the South African ('Boer') War". New Zealand History. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ↑ Totten, Samuel; Bartrop, Paul R. (2008). "Concentration Camps, South African War". Dictionary of Genocide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9780313346415.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South African Republic. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| ||||||||||||||||||