Zone of possible agreement

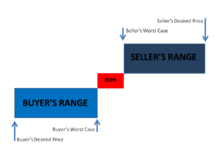

The zone of possible agreement (ZOPA), or "bargaining range",[1] describes the intellectual zone in sales and negotiations between two parties where an agreement can be met which both parties can agree to. Within this zone, an agreement is possible. Outside the zone no amount of negotiation will yield an agreement.

For example, take a person willing to lend money at a certain interest rate over a certain period of time and a person wanting to borrow money at a certain rate. If both parties can agree a rate and period then a ZOPA can be established.

An understanding of your ZOPA is critical for a successful negotiation. To determine whether there is a ZOPA both parties must explore each other’s interests and values. This should be done early in the negotiation and be adjusted as more information is learned. Once you discover your ZOPA there is a great chance you’ll come to an agreement.

Identifying a ZOPA

To determine whether there is a positive bargaining zone each party must understand their bottom line or worst case price. For example, Paul is selling his car and refuses to sell it for less than $5,000 (his worst case price). Sarah is interested and negotiates with Paul. If she offers him anything higher than $5,000 there is a positive bargaining zone, if she is unwilling to pay more than $4,500 there is a negative bargaining zone.

A ZOPA exists if there is an overlap between each party’s reservation price (bottom line). A negative bargaining zone is when there is no overlap. With a negative bargaining zone both parties may (and should) walk away.

Overcoming a negative bargaining zone

A negative bargaining zone may be overcome by “enlarging the pie.” In Integrative negotiations when dealing with a variety of issues and interests, parties that combine interests to create value reach a far more rewarding agreement. Behind every position there are usually more common interests than conflicting ones.[2]

In the example above Sarah is unwilling to pay more than $4,500 and Paul won’t accept anything less than $5,000. However, Sarah may be willing throw in some skis she received as a gift but never used. Paul, who was going to use some of the car money to buy some skis, agrees. Paul accepted less than his bottom line because value was added to the negotiation. Both parties “win.”

A negotiator should always start considering both parties' ZOPA at the earliest stage of his or her preparations and constantly refine and adjust these figures as the process proceeds. Remember, “for every interest there usually exists several possible solutions that could satisfy it.”[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Spangler, Brad. "Zone of Possible Agreement (ZOPA)." Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: June 2003 <http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/zopa>

- 1 2 Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes (New York: Penguin Books, 1983) pg 42.

- Roy J. Lewicki, John Minton, David Saunders, "Zone of Potential Agreement" in Negotiation, 3rd Edition. Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin-McGraw Hill, 1999.

- Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes (New York: Penguin Books, 1983).