Polish złoty

| Polish złoty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polski złoty (Polish) | |||||

| |||||

| ISO 4217 code | PLN | ||||

| Central bank | National Bank of Poland | ||||

| Website |

www | ||||

| User(s) |

| ||||

| Inflation | -1.3% | ||||

| Source | [1] (April 2015) | ||||

| Subunit | |||||

| 1/100 | Grosz | ||||

| Symbol | zł | ||||

| Grosz | gr | ||||

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency belong(s) to the Slavic languages. There is more than one way to construct plural forms. | ||||

| Coins | 1gr, 2gr, 5gr, 10gr, 20gr, 50gr, 1zł, 2zł, 5zł | ||||

| Banknotes | 10zł, 20zł, 50zł, 100zł, 200zł | ||||

| Mint | Mennica Polska | ||||

| Website |

www | ||||

The złoty (pronounced [ˈzwɔtɨ];[2] sign: zł; code: PLN), which literally means "golden", is the currency of Poland. The modern złoty is subdivided into 100 groszy (singular: grosz, alternative plural forms: grosze; groszy). The recognized English form of the word is zloty, plural zloty or zlotys.[3] The currency sign, zł, is composed of Polish small letters z and ł (Unicode: U+007A z LATIN SMALL LETTER Z & U+0142 ł LATIN SMALL LETTER L WITH STROKE).

As a result of inflation in the early 1990s, the currency underwent redenomination. Thus, on January 1, 1995, 10,000 old złotych (PLZ) became one new złoty (PLN). Since then, the currency has been relatively stable, with an exchange rate fluctuating between 3-5 złoty for a United States dollar.

History

Before złoty

The predecessor of złoty, as it is thought by historians, were the Polish mark(hrywna) and a kopa. Hrywna was a currency that was equivalent to ca. 210 g of silver, in the XI century. It was used somewhere to the XIV century, when it gave place to the Kraków hrywna, approx. 198 g of silver. At the same time, first as the complement to hrywna, and then as the main currency, came a grosz and a kopa. Poland made grosz as the imitation of the Prague groschen, the idea of kopa came from Czechs as well. A hrywna was worth 48 groszy, a kopa cost 60 groszy.

First złoty

Kingdom of Poland and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The złoty (golden) is a traditional Polish currency unit dating back to the Middle Ages. Initially, in the 14th and 15th centuries, the name was used for all kinds of foreign gold coins used in Poland, most notably Venetian and Hungarian ducats. One złoty at the very beginning of their introduction cost 12-14 groszy, however, groszy had less and less silver as the time passed. In 1496 the Sejm approved the creation of a national currency, the złoty, and its value was set at 30 groszy, a coin minted since 1347 and modelled on the Prague groschen. The 1:30 proportion stayed(1/2 of a kopa), but grosz was cheaper and cheaper. In the beginning of the XVI century the production of 1 złoty was worth 32 groszy, by the middle of the same century it was 50 groszy.

Coins of Poland after the monetary reform of 1526-1528:

- szeląg(shilling) cost ⅓ grosza;

- półgrosz, which cost ½ grosza, was removed;

- grosz was the base of the Polish currency(introduced in 1367);

- półtorak (1½ grosze) was circulating from 1614 to 1660;

- dwojak (2 grosze) was produced sporadically, mainly at the reign of John II Casimir Vasa;

- trojak (3 grosze) was made from 1528;

- czworak (4 grosze) were circulating in 1565-68;

- szóstak (6 groszy) were introduced in 1528 and stopped circulating in 1764;

- ort (18 groszy) were minted from 1609 to 1756;

- półkopek (1 złoty) was made from 1564 to till 1841. The first coin(with the weight of 6.726 g that had only 3.36 g of silver) was minted in Vilnius. The coin initially showed the nominal of 30 groszy(XXX). From 1663 the coin was called złoty, or as well "tymf", called so because the designer was the German Andreas Tymf, or złotówka.

| Golden coins of the XIV century[4] | The golden coin of the XIV century | |

|---|---|---|

Latin: "DEI GRATIA REX POLONIÆ", "KAZIMIRVS PRIMUS"("From the God's will, the King of Poland", "Kazimierz I") |

Latin: «GROSI CRACOVIENSESS» («Kraków grosz») |

40 ducates of Sigismund III Vasa; Latin: "Poloniæ et Svegiæ rex"(The King of Poland and Sweden) |

The name złoty (sometimes referred to as the florin) was used for a number of different coins, including the 30 groszy coin called the polski złoty, the czerwony złoty (Red złoty) and the złoty reński (the R

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

hine guilder), which were in circulation at the time. However, the value of the Polish złoty dropped over time relative to these foreign coins and it became a silver coin, with the foreign ducats eventually circulating at approximately 5 złotych.

Following the monetary reform carried out by King Stanisław August Poniatowski, the złoty became Poland's official currency and the exchange rate of 1 złoty to 30 groszy was confirmed. The King came to the system, which had the base of the Kölner mark(233.855 g of pure silver). Each mark was divided in 10 Conventionsthaler of the Holy Roman Empire, and 1 thaler cost 8 złotych(consequently, 1 złoty cost 4 groschen). The system was in place until 1787. Two debasements of the currency occurred in the years before the final partition of Poland.

After the III partition of Poland, the name złoty existed only in Austrian and Russian lands. Prussia had introduced mark instead.

The Kościuszko Insurrection and Russian part of Poland until 1807

On 8 June 1794 the decision of the Polish Supreme Council offered to make the new banknotes as well as the coins. 13 August 1794 was the date when the złoty banknotes were released to public. At the day there was more than 6.65 million złotych given out by the rebels. There were banknotes with the denomination of 5;10;25;50;100;500 and 1000 złotych, as well as 5; 10 groszy, 1 and 4 złoty coins(later banknotes).

However, it didn't last for long: on 8 November, Warsaw was already held by Russiana. Russians discarded all the banknotes and declared them invalid. Russian coins and banknotes replaced the Kościuszko banknotes, but the division on złote and grosze stayed. This can be explained by the fact the Polish monetary system, even in the deep crisis, was better than the Russian stable one, as Poland used the silver standard for coins. That is why Mikhail Speransky offered to come to silver monometalizm("count on the silver ruble") in his work «План финансов»("Financial Plans", 1810) in Russia. He argued that: "...at the same time... forbid any other account in Livonia and Poland, and this is the only way to unify the financial system of these provinces in the Russian system, and as well they will stop, at least, the damage that pulls back our finances for so long."

Duchy of Warsaw

The złoty remained in circulation after the Partitions of Poland and the Duchy of Warsaw issued coins denominated in grosz, złoty and talar (plurals talary and talarów), worth 6 złoty. Talar banknotes were also issued.

Congress Poland

On 19 November(1 December) 1815, the law about the monetary system of the Congress Poland(in Russia), according to which the złoty stayed, but there was a fixed ratio of ruble to złoty: 1 złoty cost 15 silver groszy, while 1 grosz cost ½ silver kopecks. From 1816, the złoty started being issued by the Warsaw mint, nominated in grosze and złote with the Polish writing on it., and as well of the portrait of Alexander ITand/or the Russian Empire's coat of arms:

- 1 and 3 grosze made from copper;(1815–49)

- 5 and 10 groszy out of billon;(1816–55)

- 1, 2, 5 and 10 złotych out of silver;(1816–55)

- 25 and 50 złotych out of gold;(1817–34).

At the same time the kopecks were allowed to be circulated in the Congress Poland. In fact foreign coins circulated(of Austrian Empire and Prussia), and the Polish złoty itself was paradoxically a foreign currency. The coins were as well used in the western part of Russian Empire, legally from 1827(decision of the State Council).

In 1828 the Polish mint was allowed to print banknotes of the denomination of 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 złotych, on the condition of their guaranteed exchange on coins at the will of Saint Petersburg. That meant that there should have been some silver coins that had the value of 1/7 of banknotes in circulation.

November Uprising

At the time of the November Uprising, the rebels released their own "rebellion money" - the golden ducats and silver coins of the denomination of 2 and 5 złotych, with the revolutional coat of arms. 1 złoty coin was as well released as a trial coin. Polish bank under the control of the rebels, having few noble metal resources in the reserves, released the 1 złoty banknote. By August 1831 735 thousand złotych were released as banknotes. After the defeat of the uprising the decisions from 21 November(3 December) and 18(30) December cancelled all the uprising monetary politics. All the coins were to be replaced by Russian coins, but it took a long time till the currency was circulating - only in 1838 the usage of rebel money was banned.

At the same time the question arose about the future of the Polish złoty, as well as about drastically limiting of the Polish banking autonomy. The Russian finance minister Georg von Cancrin suggested to "count all in rubles, not florins". Under "florins" złoty was meant.

The Warsaw mint issued grosz and złoty until 1832, when it began to issue coins denominated in both Polish and Russian currencies. From 1842, the Warsaw mint issued regular type Russian coins along with some coins denominated in both grosz and kopeck. In 1850, the last coins bearing Polish denominations were minted. Between 1835 and 1846, the Free City of Kraków also issued a currency, the Kraków złoty.

Currencies of Congress Poland - Ruble and Mark

From 1850, the only currency issued for use in Congress Poland was the rubel consisting of Russian currency and notes of the Bank Polski. The monetary system of Congress Poland was unified with the Russian Empire following the failed January Uprising in 1863. However, the gold coins remained in use until the early 20th century, much like other gold coins of the epoch, most notably gold roubles (dubbed świnka, or piggy) and sovereigns. Following occupation of the Congress Poland by Germans during World War I in 1917, the rubel was replaced by the marka (plurals marki and marek), a currency initially equivalent to the German Papiermark.

Second złoty

Second Republic

The złoty was reintroduced as Poland's currency by Władysław Grabski in 1924, following the hyperinflation and monetary chaos of the years after World War I. It replaced the marka at a rate of 1 złoty = 1,800,000 marek and was subdivided into 100 groszy. The złoty was pegged at 0.1687 grams pure gold. 1 1939-złoty = 8 2004-złoty.

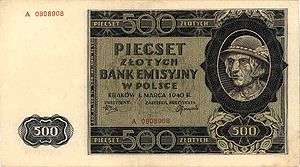

General Government

On December 15, 1939, the new Bank Emisyjny was established by the General Government, itself set up by Nazi Germany. In May 1940, old banknotes of 1924–1939 were stamped by the new entity. The money exchange was limited per individual, the limits varied according to the status of the person (Pole, Jew, etc.). The fixed exchange rate 1 Reichsmark = 2 złote was established. A new issue of notes appeared in 1941. The General Government also issued coins using similar designs to earlier types but with cheaper metals.

Lublin Poland

New złoty banknotes were introduced after July 22, 1944 by the Narodowy Bank Polski. They circulated until 1950.

Third złoty

In 1950, a new złoty (PLZ) was introduced, replacing all earlier issues at a rate of one hundred to one. The new banknotes were dated 1948, while the new coins were dated 1949. Initially by law from 1950 1 złoty (zł) = 0.222168 g of pure gold, see also Dziennik Ustaw 50, 459. From January 1, 1990 it was a convertible currency.

Between 1950 and 1990, a unit known as the złoty dewizowy (which can be roughly translated as the foreign exchange złoty) was used as an artificial currency for calculation purposes only. It existed because at the time the złoty was not convertible and its official rate of exchange was set by the Government, and there existed several exchange rates depending on the purpose of the transaction and who was exchanging, i.e. a given amount in złoty could be exchanged for say US dollars at one of several official exchange rates depending on what was to be bought for the hard currency and the company that was buying foreign exchange; it worked similarly when a company had some earnings in Western currency and wanted (or needed) to convert them into złotych. The exchange rate did not depend on the amount being converted. Visitors from countries outside of the Soviet Bloc were offered a particularly poor exchange rate. Concurrently, the private black-market exchange rate contrasted sharply with the official government exchange rate until the end of Communist rule in 1989 when official rates were tied to market rates.

Fourth złoty

The new Polish złoty (PLN) is the unofficial name of the current currency of Poland, introduced on January 1, 1995 as a result of the redenomination of the old currency. The official name of the Polish currency did not change since the Polish currency law of 1950 (DZ.U nr 50. poz. 459 with later changes), which defines the official currency as the złoty, up to one million denominated notes remains in effect. The redenomination rate was 10,000 old Polish złoty to 1 new Polish złoty. The issuing bank is the National Bank of Poland. See also original law from 7 July 1994 Dziennik Ustaw Nr 84, 386

Future

Conditions of Poland's joining the European Union (in May 2004) oblige the country to eventually adopt the euro, though not at any specific date and only after Poland meets the necessary stability criteria. Serious discussions of joining the Eurozone have ensued.[5][6][7] However, article 227[8] of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland will need to be amended first,[9] so it seems unlikely that Poland will adopt the euro before 2019.[10] Public opinion research by CBOS from March 2011 shows that 60% of Poles are against changing their currency. Only 32% of Poles want to adopt the euro, compared to 41% in April 2010.[11]

Coins

First złoty coins

In the late 18th century, coins were issued in denominations of 1⁄3, 1⁄2, 1, 3, 6, 7 1⁄2, 10 and 15 groszy, 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8 złotych. The 1⁄3 and 1⁄2 grosz were denominated as the solidus and polgrosz, whilst the 7 1⁄2 and 15 groszy (copper) were denominated as 1 and 2 silver groschen. Coins up to 3 grosz were minted in copper, those between 6 and 15 grosz were billon whilst the denominations from 1 złoty upward were in silver.

The Duchy of Warsaw issued copper 1 and 3 grosze, billon 5 and 10 groszy and silver 1⁄6, 1⁄3 and 1 talar. After 1816, the Congress Poland issued copper 1 and 3 grosze, billon 5 and 10 groszy, silver 1, 2, 5 and 10 złotych, and gold 25 and 50 złotych. During the insurrection of 1831, coins were minted for 3 and 10 groszy, 2 and 5 złotych.

Between 1832 and 1834, coins denominated in both Polish and Russian currencies were issued, for 1 złoty (15 kopeck), 2 złote (30 kopeck), 5 złotych (3⁄4 ruble), 10 złotych (1 1⁄2 ruble) and 20 złotych (3 ruble). These were issued, along with the copper and billon coins, until 1841. In 1842, Russian coins were introduced, supplemented by 40 groszy (20 kopeck) and 50 groszy (25 kopeck) coins. These two coins were issued until 1850.

Second złoty coins

In 1924, coins were introduced in denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 groszy, 1 and 2 złote. The lowest three denominations were first minted in brass, then in bronze. The 10, 20 and 50 groszy were in nickel, with the higher denominations in silver. Gold 10 and 20 złotych coins were minted in 1925. Silver 5 złotych coins were introduced in 1928. The size of the silver coins was reduced in 1932, a move accompanied by the introduction of silver 10 złotych coins. During the German occupation of World War II, 1, 5, 10 and 20 groszy coins were issued (dated 1923) in zinc and 50 groszy (dated 1938) in nickel plated iron or iron.

Third złoty coins

In 1950, coins were issued for 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 groszy and 1 złoty. All denominations were minted in aluminium. Previously (1949) the 5 groszy was minted in bronze, the denominations above 5 groszy minted in cupro-nickel and 1 and 2 groszy were in aluminium. From 1957, aluminium coins for 5, 10, 20 and 50 groszy and 1 złoty were issued, with aluminium 2 and 5 złotych introduced in 1958. Cupro-nickel 10 and 20 złotych followed in 1959 and 1973, respectively. Brass 2 and 5 złotych were introduced in 1975, reverting to aluminium in 1989. In 1990, 1 (aluminium), 10, 20, 50 and 100 złotych coins were issued, although they saw little circulation due to the high inflation occurring at that time.

Fourth złoty coins

Coins were introduced in 1995 (dated from 1990) in denominations of 1, 2, 5 (colloquially called miedziaki corresponding to its copper colour or dziady as coins with very low value and identified with poor people), 10, 20 and 50 groszy, 1 (colloquially called złotówka), 2 (colloquially called dwójka) and 5 złotych (colloquially called piątka). The 1, 2, and 5 groszy are minted in brass, and the 10, 20 and 50 groszy and 1 złoty in cupro-nickel, whilst the 2 and 5 złotych are bimetallic. 10, 20, 25, 50, 100, 200 and 500 złotych coins also exist and are legal tender, but are not in normal circulation. The 5, 10, 20 złotych coins are often made of silver whilst the 25, 50, 100, 200, 500 złotych coins are made of gold. They are minted by the Mint of Poland and issued by the Bank of Poland for the main purpose of numismatics. Until 2014, commemorative 2 zl coins were issued every year, an average of 20 annually, made of Nordic Gold; they are legal tender, but not recommended for circulation. In 2014, the Polish Mint introduced new versions of the 1, 2, and 5 groszy minted in brass-plated steel.

Emission

The emission of zloty and grosz coins are shown in the tables.[12]

| Year/coin | 5 zł | 2 zł | 1 zł | 50 gr | 20 gr | 10 gr | 5 gr | 2 gr | 1 gr |

| 1990 | 20,240,000 | 29,152,000 | 25,100,000 | 43,055,000 | 70,240,000 | 34,400,000 | 29,140,000 | ||

| 1991 | 60,080,000 | 99,120,000 | 75,400,000 | 123,164,300 | 171,040,000 | 97,410,000 | 79,000,000 | ||

| 1992 | 102,240,000 | 116,000,000 | 106,100.001 | 210,000,005 | 103,784,000 | 157,000,003 | 362,000,000 | ||

| 1993 | 20,904,000 | 84,240,008 | 20,280,101 | 80,780,000 | |||||

| 1994 | 112,896,033 | 79,644,000 | 69,956,000 | ||||||

| 1995 | 122,880,020 | 99,740,122 | 101,600,113 | 102,280,109 | |||||

| 1996 | 52,940,003 | 29,745,000 | |||||||

| 1997 | 59,755,000 | 92,400,002 | 103,080,002 | ||||||

| 1998 | 52,500,000 | 62,695,000 | 93,472,002 | 154,840,050 | 257,640,003 | ||||

| 1999 | 25,985,000 | 47,040,000 | 99,024,000 | 187,900,000 | 203,970,000 | ||||

| 2000 | 52,135,000 | 104,060,000 | 75,600,000 | 94,500,000 | 210,100,000 | ||||

| 2001 | 41,980,001 | 62,820,000 | 67,368,000 | 84,000,000 | 210,000,020 | ||||

| 2002 | 10,500,000 | 10,500,000 | 67,200,000 | 83,910,000 | 240,000,000 | ||||

| 2003 | 20,400,000 | 31,500,000 | 48,000,000 | 80,000,000 | 250,000,000 | ||||

| 2004 | 40,000,025 | 70,500,000 | 62,500,000 | 100,000,000 | 300,000,000 | ||||

| 2005 | 5,000,000 | 37,000,025 | 94,000,000 | 113,000,000 | 163,003,250 | 375,000,000 | |||

| 2006 | 5,000,000 | 35,000,000 | 40,000,000 | ||||||

| 2007 | 20,000,000 | 68,000,000 | 100,000,000 | 116 000 000 | 160 000 000 | 330,000,000 | |||

| 2008 | 5,000,000 | 15,000,000 | 5,000,000 | 13,000,000 | 91,000,000 | 103,000,000 | 107,000,000 | 172,000,000 | 316,000,000 |

| 2009 | 59,000,000 | 62,000,000 | 34,000,000 | 57,000,000 | 133,000,000 | 146,000,000 | 160,000,000 | 222,000,000 | 338,000,000 |

| 2010 | 30 000 000 | 15,000,000 | 3,000,000 | 12,000,000 | 45,000,000 | 62,000,000 | 100,000,000 | 120,000,000 | 150,000,000 |

| 2011 | 10,000,000 | 15,000,000 | 80,000,000 | 90,000,000 | 150,000,000 | 270,000,000 | |||

| 2012 | 10,000,000 | 12,000,000 | 38,000,000 | 136,000,000 | 60,000,000 | 100,000,000 | 365,000,000 | ||

| 2013 | 21,000,000 | 30,000,000 | 36,000,000 | 142,000,000 | 88,000,000 | 150,000,000 | 323,000,000 | ||

| 2014 | 28,000,000 | 35,250,000 | 28,400,000 | 46,000,000 | 88,000,000 | 96,004,500 | 137,084,750 | 420,924,900 | |

| 2015 | 38,040,000 | 34,350,000 | 39,000,000 | 44,010,000 | 78,030,000 | 112,050,000 | 115,050,000 | 129,870,000 | 388,560,000 |

Banknotes

First złoty banknotes

In 1794, treasury notes were issued in denominations of 5 and 10 groszy, 1 złoty, 4 złote, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 złotych. The Duchy of Warsaw issued notes for 1, 2 and 5 talarów.

In 1836, the Bank Kassowy Królestwa Polskiego issued notes for 10, 50 and 100 złotych. The Bank Polski issued notes dated 1830 and 1831 in denominations of 1, 5, 50 and 100 złotych, whilst assignats for 200 and 500 złotych were issued during the insurrection of 1831. From 1841, the Bank Polski issued notes denominated in rubel.

Second złoty banknotes

In 1924, along with provisional notes (overprints on old, bisected notes) for 1 and 5 groszy, the Ministry of Finance issued notes for 10, 20 and 50 groszy, whilst the Bank Polski introduced 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 złotych. From 1925, the Ministry of Finance issued 2 and 5 złotych notes, before they were replaced by silver coins, and the Bank Polski issued 5, 10, 20 and 50 złotych notes, with 100 złotych only reintroduced in 1932. In 1936, the Bank Polski issued 2 złote notes, followed in 1938 by Ministry of Finance notes for 1 złoty.

In 1939, the General Government overprinted 100 złotych notes for use before, in 1940, the Bank Emisyjny w Polsce was set up and issued notes for 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 złotych. After liberation, notes (dated 1944) were introduced by the Narodowy Bank Polski for 50 grosz, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 złotych, with 1000 złotych notes added in 1945.

| Second złoty banknotes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picture | Denomination | Size | Color | Obverse | Reverse | Date of print | Date of withdrawal | ||

.jpg) | | |

| | |

2 zł | 102 мм x 63 мм | Dark gray | Denomination and portrait of a Doubravka of Bohemia |

Denomination and Coat of Arms of Poland | 1936 | 1940 | |

.jpg) | | |

| | |

5 zł | 144 мм x 78 мм | Navy blue | Denomination and portrait of a woman |

Bank of Poland caption | 1930 | ||

| | |

| | |

10 zł | 160 мм x 80 мм | Light brown | Denomination in the center and images of saints | Three figures: a woman with a model ship, a worker and a farmer | 1929 | ||

| | |

| | |

20 zł | 163 мм x 86 мм | Gray, blue | Portrait of Emilia Plater and sculpture of a woman with two children | Wawel Castle and Wawel Cathedral | 1936 | ||

| | |

| | |

50 zł | 188 мм x 99 мм | Green, blue and brown | Denomination in the center and images of a farmer and a worker | Images of memorable buildings in Warsaw | 1929 | ||

| | |

| | |

100 zł | 175 мм x 98 мм | Brown | Portrait of Prince Józef Poniatowski | An oak representing the history of Poland | 1934 | ||

Third złoty banknotes

In 1950, new notes (dated 1948), were introduced for 2 złote, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 złotych. 1000 złotych notes were added in 1962. 200 and 2000 złotych notes were added in 1976 and 1977, followed by 5000 złotych notes in 1982. The late 1980s and early 1990s saw high inflation in Poland and led to the introduction of notes in denominations of 10,000 (in 1987), 20,000 (1989), 50,000 (1989), 100,000 (1990), 200,000 (1989), 500,000 (1990), 1,000,000 (1991) and 2,000,000 złotych (1992). A possible 5,000,000 zlotych banknotes with the portrait of Marshall Jozef Pilsudski was in planning, but scrapped after the fall of Communism. These notes (and coins of course) were valid (with the exception of the 200,000 one) until the end of 1996. They could be exchanged at the National Bank of Poland (and some banks obligated to it by the NBP) until December 31, 2010; they are no longer legal tender.

Fourth złoty banknotes

In 1995, notes were introduced in denominations of 10 (colloquially called dycha), 20, 50, 100 (colloquially called stówa or stówka) and 200 złotych. Since 2006 several commemorative banknotes for collectors have been issued.

On September 24, 2013, the National Bank of Poland presented new banknotes in denominations of 10, 20, 50 and 100 złotych. The designs of the originals have remained unchanged, but the security features have been improved, such as, among others, an outdoor field watermark, enhanced security on both front and back, and the introduction of an opaque paint. The new banknotes were put into circulation on April 7, 2014. On June 23, 2015, a new banknote of 200 złotych was presented, which is planned for introduction in February 2016 and also announced plans of introduction of a new denomination of 500 złotych with Jan III Sobieski in 2017. All old banknotes from the 1994 series are valid indefinitely.[13]

| First series, "Sovereigns of Poland", (1994)[14] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Watermark | Description | Date of | ||||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | printing | issue | annul | |||

_note.jpg) |

10 zł | 120 × 60 mm | As portrait | Mieszko I | Silver denar coin during the reign of Mieszko I | 25 March 1994 | 1 January 1995 | current | |

|

20 zł | 126 × 63 mm | Bolesław I the Brave | Silver denar coin during the reign of Bolesław I Chrobry | |||||

|

50 zł | 132 × 66 mm | Casimir III the Great | White Eagle from the royal seal of Casimir III the Great and the regalia of Poland: sceptre and globus cruciger | |||||

|

100 zł | 138 × 69 mm | Władysław II Jagiełło | Shield bearing a White Eagle from the tombstone of Władysław II Jagiełło, coat of the Teutonic Knights and the Grunwald Swords | 1 June 1995 | ||||

|

200 zł | 144 × 72 mm | Sigismund I the Old | Eagle intertwined with the letter S in a hexagon, from the Sigismund's Chapel | |||||

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixels per millimeter. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | |||||||||

| Second series, "Sovereigns of Poland", (2012) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Watermark | Description | Date of | ||||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | printing | issue | annul | |||

| 10 zł | 120 × 60 mm | As portrait | Mieszko I | Silver denar coin during the reign of Mieszko I | 5 January 2012 | 7 April 2014 | current | ||

| 20 zł | 126 × 63 mm | Bolesław I the Brave | Silver denar coin during the reign of Bolesław I Chrobry | ||||||

| 50 zł | 132 × 66 mm | Casimir III the Great | White Eagle from the royal seal of Casimir III the Great and the regalia of Poland: sceptre and globus cruciger | ||||||

| 100 zł | 138 × 69 mm | Władysław II Jagiełło | Shield bearing a White Eagle from the tombstone of Władysław II Jagiełło, coat of the Teutonic Knights and the Grunwald Swords | ||||||

| 200 zł | 144 × 72 mm | Sigismund I the Old | Eagle intertwined with the letter S in a hexagon, from the Sigismund's Chapel | 30 March 2015 | 12 February 2016 | ||||

| 500 zł | 150 × 75 mm | As portrait ? | John III Sobieski | ? | ? | 2017 (TBA) | planned | ||

These images are to scale at 0.7 pixels per millimeter. For table standards, see the banknote specification table.

Exchange rates

| Year | USD | EUR | DEM | GBP | CHF | JPY |

| 1990 | 9500,00 | 12070,50 | 5864,19 | 16862,50 | 6884,05 | 6545,00 |

| 1991 | 10584,26 | 13088,29 | 6378,62 | 18 652,81 | 7379,05 | 7872,35 |

| 1992 | 13630,12 | 17662,35 | 8761,51 | 24009,90 | 9742,76 | 10777,66 |

| 1993 | 18164,84 | 21204,91 | 10975,20 | 27274,86 | 12308,00 | 16416,00 |

| 1994 | 22726,95 | 26913,49 | 14049,60 | 34772,23 | 16670,93 | 22416,00 |

| Re-denomination | ||||||

| 1995 | 2,4244 | 3,1358 | 1,6928 | 3,8257 | 2,0545 | 0,0258 |

| 1996 | 2,6965 | 3,3774 | 1,7920 | 4,2154 | 2,1826 | 0,0248 |

| 1997 | 3,2808 | 3,7055 | 1,8918 | 5,3751 | 2,2627 | 0,0272 |

| 1998 | 3,4937 | 3,9231 | 1,9888 | 5,7907 | 2,4149 | 0,0268 |

| 1999 | 3,9675 | 4,2270 | 2,1612 | 6,4197 | 2,6413 | 0,0350 |

| 2000 | 4,3464 | 4,0110 | 2,0508 | 6,5787 | 2,5747 | 0,0403 |

| 2001 | 4,0939 | 3,6685 | end 1,9558 | 5,8971 | 2,4298 | 0,0337 |

| 2002 | 4,0795 | 3,8557 | – | 6,1293 | 2,6288 | 0,0329 |

| 2003 | 3,8889 | 4,3978 | – | 6,3570 | 2,8911 | 0,0339 |

| 2004 | 3,6540 | 4,5340 | – | 6,6904 | 2,9370 | 0,0337 |

| 2005 | 3,2348 | 4,0254 | – | 5,8833 | 2,5999 | 0,0294 |

| 2006 | 3,1025 | 3,8951 | – | 5,7116 | 2,4761 | 0,0266 |

| 2007 | 2,7667 | 3,7829 | – | 5,5310 | 2,3035 | 0,0235 |

| 2008 | 2,3708 | 3,4908 | – | 4,2200 | 2,2291 | 0,0234 |

| 2009 | 3,1175 | 4,3276 | – | 4,8563 | 2,8665 | 0,0333 |

| 2010 | 3,0179 | 3,9939 | – | 4,6587 | 2,8983 | 0,0345 |

| 2011 | 2,9636 | 4,1190 | – | 4,7463 | 3,3474 | 0,0373 |

| 2012 | 3,2581 | 4,1852 | – | 5,1605 | 3,4724 | 0,0409 |

| 2013 | 3,1608 | 4,1975 | – | 4,9437 | 3,4100 | 0,0324 |

| Current PLN exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From XE: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From fxtop.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From Currency.Wiki: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

Name and plural forms

The name złoty is pronounced like zwoti. There are two plural forms: złote (zwoteh) and złotych (zwotikh), which usage is based on old polish system of singular, double and plural form. The correct usage of plural forms is as following:

- 1 złoty/grosz

- 2…4; 22…24; 32…34 (…), 102…104, 122…124, 132…134, (…) złote/grosze

- 0, 5…21; 25…31; 35…41 (…); 95…101; 105…121; 125…131; (…) złotych/groszy

and so on, e.g. 1,000,000 złotych; 1,000,002 złote; 1,000,011 złotych; 1,000,024 złote. Fractions should be rendered along with word złotego and grosza, e.g. 0.1 złotego; 2.5 złotego etc. It is customary in Poland to use space (non-breaking) for digit grouping (“thousands separator”) and comma for separating fractions from whole numbers; cf. decimal mark.

Here one can find general rules for declension of cardinal (among others) numerals in Polish: classes one, few, many and other for “złoty” are złoty, złote, złotych, złotego respectively and for “grosz” are grosz, grosze, groszy, grosza respectively.

See also

- Commemorative coins of Poland

- Economy of Poland

- Historical coins and banknotes of Poland

- Poland and the euro

- Polish coins and banknotes

Footnotes

- ↑ Kozłowski, Mariusz (15 April 2015). "Komentarz MG: inflacja w marcu 2015 r.". Ministerstwo Gospodarki RP. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑ The nominative plural, used for numbers ending in 2, 3 and 4 (except those in 12, 13 and 14), is złote [ˈzwɔtɛ]; the genitive plural, used for all other numbers, is złotych [ˈzwɔtɨx]

- ↑ American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 3rd ed., p. 2078.

- ↑ "Краковский грош чеканенный в 14 веке" (in Polish). www.historiapieniadza.pl. Archived from the original on 2012-01-26. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- ↑ "Poland may hold euro referendum in 2010-Deputy PM". Forbes. September 18, 2008. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Poland may push back euro rollout to 2012". The Guardian (London). Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Poland may push back euro rollout to 2012". BizPoland. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2nd April 1997, as published in Dziennik Ustaw (Journal of Laws) No. 78, item 483". Parliament of the Republic of Poland. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Polish charter must change before ERM-2". fxstreet.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ↑ Sobczyk, Marcin (May 18, 2011). "Poland Backtracks on Euro Adoption". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ↑ "CBOS za przyjęciem euro 32 proc. Polaków, przeciw 60 proc.". bankier.pl. March 28, 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ http://www.nbp.pl/home.aspx?f=/banknoty_i_monety/monety_obiegowe/naklady_emisji.html

- ↑ http://www.biztok.pl/waluty/500-zl-jednak-powstanie-jest-deklaracja-nbp_a21607

- ↑ National Bank of Poland - Internet Information Service

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Money of Poland. |

- Banknotes issued by the NBP

- Coins issued by the NBP

- A fan-shaped 10 złoty commemorative coin released in 2004

- National Bank of Poland – Schedule of exchange rates

- "English" counterfeit banknote 500 zloty 1940 issued by Bank Emisyjny

- Chosen Polish banknotes

- Polish Zloty coins catalog information

- A numismatic catalog with over 650 Polish coins

- "NBP Safe" - official app dedicated to Polish money

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.gif)