Zenobia

| Zenobia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zenobia Antoninianus coin reporting her title, Augusta and showing her diadem and draped bust on a crescent with the reverse showing a standing figure of Iuno Regina, holding a patera in her right hand, a sceptre in her left, a peacock at her feet, and a brilliant star to the right | |||||

| Queen of the Palmyrene Empire | |||||

| Born | Palmyra, Syria | ||||

| Spouse | Septimius Odaenathus | ||||

| Issue | Lucius Julius Aurelius Septimius Vaballathus Athenodorus | ||||

| |||||

| House | Emesa | ||||

Zenobia (Greek: Ζηνοβία / Zēnobía; Aramaic: בת זבי / Bat-Zabbai; Arabic: الزباء / al-Zabbā’; 240 – c. 275) was a 3rd-century Queen of the Palmyrene Empire in Syria who led a famous revolt against the Roman Empire. The second wife of King Septimius Odaenathus, Zenobia became queen of the Palmyrene Empire following Odaenathus' death in 267. By 269, Zenobia had expanded the empire, conquering Egypt and expelling the Roman prefect, Tenagino Probus, who was beheaded after he led an attempt to recapture the territory. She ruled over Egypt until 271, when she was defeated and taken as a hostage to Rome by Emperor Aurelian.

Family, ancestry and early life

Zenobia was born and raised in Palmyra, Syria. Her Roman name was "Julia Aurelia Zenobia" and Latin and Greek writers referred to her as "Zenobia"[1] (Greek: ἡ Ζηνοβία) or as "Septimia Zenobia"—she became Septimia after marrying Septimius Odaenathus. She used the Aramaic form "Bat-Zabbai" (בת זבי) to sign her name.[1] Arabic-language writers refer to her as "al-Zabba'" (الزباء).[1]

She belonged to a family with Aramaic names.[2] She herself claimed descent from the Seleucid line of the Cleopatras and the Ptolemies.[3] Athanasius of Alexandria reported her as "a Jewess follower of Paul of Samosata", which would explain her strained relationship with the rabbis.[2]

Later Arabic sources provide indications of her Arab descent[4] and thus argue that her original name was Zaynab.[5] Al-Tabari, for example, writes that she belonged to the same tribe as her future husband, the 'Amlaqi, which was probably one of the four original tribes of Palmyra.[4] According to him, Zenobia's father, ‘Amr ibn al-Ẓarib, was the sheikh of the 'Amlaqi. After members of the rival Tanukh tribal confederation killed him, Zenobia became the head of the 'Amlaqis, leading them in their nomadic lifestyle to summer and winter pastures.[4]

Zenobia's father's name is unknown. She was styled Bit-Zabbai (daughter of Zabbai) in Palmyrene inscriptions.[6] In an inscription found in Palmyra, Zenobia is called the daughter of Antiochus.[6] However, this "Antiochus" is not recorded on other inscriptions and therefore neither his lineage or position is known and it is more probable that Antiochus was not the father but an ancestor of Zenobia.[6] According to the Augustan History (Aurel. 31.2), Zenobia's father's name was Achilleus and his usurper was named Antiochus (Zos. 1.60.2). The name "Julius Aurelius Zenobius" appears on a Palmyrene inscription and based only on the similarities of the names, Zenobius was suggested as the father of Zenobia. Zenobius was Governor of Palmyra in 229.[6]

Zenobia also claimed descent from Dido, Queen of Carthage and the Ptolemaic Greek Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt. Though there is no concrete evidence of this, she did have knowledge of the ancient Egyptian language, showed a predisposition towards Egyptian culture, and may have been part-Egyptian through her mother.[7] According to the Augustan History, an imperial declaration of hers in 269 was sent to the citizens of Alexandria, Egypt, describing the city as "my ancestral city". This declaration only fits Vaballathus, the son of Zenobia. The historian Callinicus dedicated a ten-book history of Alexandria to a "Cleopatra", who can only be Zenobia.

Classical and Arabic sources describe Zenobia as beautiful and intelligent, with a dark complexion, pearly white teeth, and bright black eyes.[4] She was said to be even more beautiful than Cleopatra, differing though in her reputation for extreme chastity.[4] Sources also describe Zenobia as carrying herself like a man, riding, hunting and drinking on occasion with her officers.[4] Well-educated and fluent in Greek, Aramaic, and Egyptian, with a working knowledge of Latin, she is supposed to have hosted literary salons and to have surrounded herself with philosophers and poets, the most famous of these being Cassius Longinus.[4][8]

Queen of Palmyra

Zenobia had become the second wife of Septimius Odaenathus, the King of Palmyra, by 258. She had a stepson, Hairan (Herod), a son from Odaenathus’ first marriage. There is an inscription, "the illustrious consul our lord" at Palmyra, dedicated to Odaenathus by Zenobia. Around 266, Zenobia and Odaenathus had a son, his second child, Lucius Julius Aurelius Septimius Vaballathus Athenodorus. This son Vaballathus (Latin from Aramaic והב אלת / Wahballat, "Gift of the Goddess") inherited the name of Odaenathus' paternal grandfather.[9]

In 267 Zenobia's husband and stepson were assassinated. The titled heir, Vaballathus, was only one year old, so his mother succeeded her husband and ruled Palmyra. Zenobia bestowed upon herself and her son the honorific titles of Augusta and Augustus. Zenobia conquered new territories and increased the Palmyrene Empire in the memory of her husband and as a legacy to her son. She had the stated goal of protecting the Eastern Roman Empire from the Sasanian Empire (Sassanids), for the peace of Rome; however, her efforts significantly increased the power of her own throne.

Invasions of Egypt and Anatolia

In 269 Zenobia, her army, and the Palmyrene General Zabdas violently conquered Egypt with help from their Egyptian ally, Timagenes, and his army. The Roman prefect of Egypt, Tenagino Probus and his forces tried to expel them from Egypt, but Zenobia's forces captured and beheaded Probus. She then proclaimed herself Queen of Egypt. After these initial forays, Zenobia became known as a "Warrior Queen". In leading her army, she displayed significant prowess: she was an able horse-rider and would walk three or four miles with her foot soldiers.

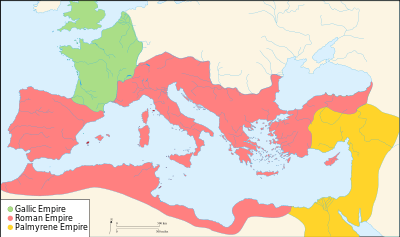

Zenobia, with her large army, made expeditions and conquered Anatolia as far as Ancyra (Ankara) and Chalcedon, followed by Syria, Palestina and Lebanon. In her short-lived empire, Zenobia took the vital trade routes in these areas from the Romans. The Roman Emperor Aurelian (reigned 270-275), who was at that time campaigning with his forces in the Gallic Empire, probably did recognise the authority of Zenobia and Vaballathus; however, this relationship began to break down when Aurelian began a military campaign to reunite the Roman Empire in 272–273. Aurelian and his forces left the Gallic Empire and arrived in Syria. The forces of Aurelian and Zenobia met and fought near Antioch. After a crushing defeat, the remaining Palmyrenes briefly fled into Antioch and then into Emesa.

Zenobia was unable to remove her treasury at Emesa before Aurelian arrived and successfully besieged the city. Zenobia and her son escaped Emesa by camel with help from the Sassanids, but Aurelian's horsemen captured them on the Euphrates River. Zenobia's short-lived Egyptian kingdom and the Palmyrene Empire had ended. Aurelian captured those remaining Palmyrenes who refused to surrender and had them executed. Those put to death included Zenobia's chief counselor, the Greek sophist Cassius Longinus.

Rome

Zenobia and Vaballathus were taken as hostages to Rome by Aurelian. Vaballathus is presumed to have died on his way to Rome. In 274, Zenobia reportedly appeared in golden chains in Aurelian’s military triumph parade in Rome, in the presence of the senator Marcellus Petrus Nutenus. There are competing accounts of Zenobia's own fate: some versions suggest that she died relatively soon after her arrival in Rome, whether through illness, hunger strike or beheading.[10] The happiest narrative, though, relates that Aurelian, impressed by her beauty and dignity and out of a desire for clemency, freed Zenobia and granted her an elegant villa in Tibur (modern Tivoli, Italy). She supposedly lived in luxury and became a prominent philosopher, socialite and Roman matron. Zenobia is said to have married a Roman governor and senator whose name is unknown, though there is reason to think it may have been Marcellus Petrus Nutenus. They reportedly had several daughters, whose names are also unknown but who are reported to have married into Roman noble families. She is said to have had further descendants surviving into the 4th and 5th centuries. Evidence in support of there being descendants of Zenobia, is offered by a name in an inscription found in Rome: the name of L. Septimia Patavinia Balbilla Tyria Nepotilla Odaenathiania incorporates the names of Zenobia's first husband and son and may be suggestive of a family relationship (after the deaths of Odaenathus and his sons, Odaenathus had no descendants). Another possible descendant of Zenobia is Saint Zenobius of Florence, a Christian bishop who lived in the 5th century.

Zenobia in the arts

by Herbert Gustave Schmalz. Original on exhibit, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Operas

- Zenobia (1694) by Tomaso Albinoni

- Zenobia in Palmira (1725) by Leonardo Leo

- Zenobia (1761) by Johann Adolph Hasse

- Zenobia in Palmira (1789) by Pasquale Anfossi

- Zenobia in Palmira (1790) by Giovanni Paisiello

- Aureliano in Palmira (1813) by Gioachino Rossini

- Zenobia (2007) by Mansour Rahbani

Music

- Zenobia (1977) by Fairuz, written and composed by the Rahbani Brothers

Literature

- Chaucer tells a condensed story of Zenobia's life in one of a series of "tragedies" in The Monk's Tale.

- La gran Cenobia (1625) by Pedro Calderón de la Barca

- The Living Wood (1947) by Louis de Wohl contains many references to Zenobia.

- The Queen of the East (1956) by Alexander Baron

- Daughter of Sand and Stone (2015) by Libbie Hawker

Sculpture

- Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra (1857) by Harriet Hosmer, Art Institute of Chicago

- Zenobia in Chains (1859) by Harriet Hosmer, Saint Louis Art Museum

Painting

- "Queen Zenobia addressing her soldiers" (1725–1730) by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, NGA Washington D.C.

Characters named for Zenobia

Zenobia has become a popular name for exotic or regal female characters in many other works, including Bertrice Small's "Beloved", Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Blithedale Romance, P.G. Wodehouse's Joy in the Morning, William Golding's Rites of Passage, Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land, Surrealist author Gellu Naum's Zenobia and in Robert E. Howard's Conan series, Edward Gorey's "Fletcher and Zenobia", and Zenobia/Zeena in Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton. She is briefly mentioned in the book Blameless from Gail Carriger's Parasol Protectorate. Her Venus-like reality while in Milan for the Carnival festivities is celebrated in the Memoirs of Jaques Casanova, chapters XIX and XX.

References

- 1 2 3 Stoneman, 1995,p. 2.

- 1 2 Teixidor, Javier (2005). A journey to Palmyra: collected essays to remember. Brill. p. 218. ISBN 978-90-04-12418-9.

- ↑ Teixidor, Javier (2005). A journey to Palmyra: collected essays to remember. Brill. p. 201. ISBN 978-90-04-12418-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ball, p. 78.

- ↑ Charlotte Mary Yonge, History of Christian names. By the author of The heir of Redclyffe, 1884, p. 62

- 1 2 3 4 Southern, Pat (2008). Empress Zenobia: Palmyra s Rebel Queen. p. 4.

- ↑ Sue M. Sefscik. "Zenobia". Women's History. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ↑ Choueiri, 2000, p. 35.

- ↑ Teixidor, Javier (2005). A journey to Palmyra: collected essays to remember. Brill. p. 213. ISBN 978-90-04-12418-9.

- ↑ Ball, Warwick. "Rome in the East" (Routledge, 2000).

Bibliography

- Ball, Warwick (2001). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. (Illustrated, reprint ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9780415243575.

- Choueiri, Youssef M. (2000). Arab Nationalism - a History: Nation and State in the Arab World. (Illustrated ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780631217299.

- Stoneman, Richard (1995). Palmyra and its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt against Rome. (Reprint, illustrated ed.). University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472083155.

- Wilden, Anthony (1987). Man and Woman, War and Peace: the Strategist's Companion. (Illustrated ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9780710098672.

Additional reading

- Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Historia Augusta

- The Monkes Tale – Geoffrey Chaucer, Notes to the Canterbury Tales

- Zenobia of Palmyra. Agnes Carr Vaughn, 1967, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc.

- Zenobia of Palmyra: History, Myth and the Neo-Classical Imagination, Rex Winsbury, 2010, Duckworth, ISBN 978-0-7156-3853-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zenobia. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Zenobia |

- Zenobia and Longinus

- Vaballathus and Zenobia

- Zenobia: empress of Palmyra (267–272)

- Zenobia as a third-century queen of Palmyra

- Zenobia-Halabiya fortress on Euphrates

- Project Continua: Biography of Zenobia Project Continua is a web-based multimedia resource dedicated to the creation and preservation of women’s intellectual history from the earliest surviving evidence into the 21st Century.

|