Horizontal coordinate system

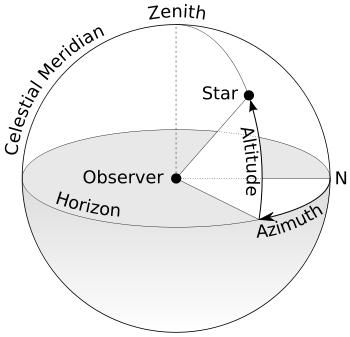

The horizontal coordinate system is a celestial coordinate system that uses the observer's local horizon as the fundamental plane. It is expressed in terms of altitude (or elevation) angle and azimuth.

Definition

This coordinate system divides the sky into the upper hemisphere where objects are visible, and the lower hemisphere where objects cannot be seen since the Earth obstructs vision. The great circle separating hemispheres is called celestial horizon or rational horizon. The celestial horizon can be defined as "the great circle on the celestial sphere whose plane is normal to the local gravity vector". In practice, the horizon can be defined as the plane tangent to a still liquid surface such as a pool of mercury.[1] The pole of the upper hemisphere is called the zenith. The pole of the lower hemisphere is called the nadir.[2]

There are two independent horizontal angular coordinates:

- Altitude (Alt), sometimes referred to as elevation, is the angle between the object and the observer's local horizon. For visible objects it is an angle between 0 degrees to 90 degrees.

- Alternatively, zenith distance, the distance from directly overhead (i.e. the zenith) may be used instead of altitude. The zenith distance is the complement of altitude (i.e. 90°-altitude).

- Azimuth (Az), that is the angle of the object around the horizon, usually measured from the north increasing towards the east. Exceptions are, for example, ESO's FITS convention where it is measured from the south increasing towards the west, or the FITS convention of the SDSS where it is measured from the south increasing towards the east.

The horizontal coordinate system is sometimes also called the az/el system,[3] the Alt/Az system, or the altazimuth system[4] (from the name of the altazimuth mount for telescopes, whose two axes follow altitude and azimuth).

Calculation

More details on the computation of azimuth and zenith angle can be found at Solar azimuth angle and Solar zenith angle.

General observations

The horizontal coordinate system is fixed to the Earth, not the stars. Therefore, the altitude and azimuth of an object in the sky changes with time, as the object appears to drift across the sky with the rotation of the Earth. In addition, because the horizontal system is defined by the observer's local horizon, the same object viewed from different locations on Earth at the same time will have different values of altitude and azimuth.

Horizontal coordinates are very useful for determining the rise and set times of an object in the sky. When an object's altitude is 0°, it is on the horizon. If at that moment its altitude is increasing, it is rising, but if its altitude is decreasing, it is setting. However, all objects on the celestial sphere are subject to diurnal motion, which is always from east to west. One can determine whether altitude is increasing or decreasing by instead considering the azimuth of the celestial object:

- if the azimuth is between 0° and 180° (north–east–south), it is rising.

- if the azimuth is between 180° and 360° (south–west–north), it is setting.

There are the following special cases:

- As seen from the north pole all directions are south, and from the south pole all directions are north, so the azimuth is undefined in both locations. Viewed from either pole, a star (or any object with fixed equatorial coordinates) has constant altitude, and therefore never rises or sets. The Sun, Moon, and planets can rise or set over the span of a year when viewed from the poles because their declinations are constantly changing.

- As seen from the equator, objects on the celestial poles stay at fixed points on the horizon.

Note that the above considerations are strictly speaking true for the geometric horizon only. That is, the horizon as it would appear for an observer at sea level on a perfectly smooth Earth without an atmosphere. In practice the apparent horizon has a slight negative altitude due to the curvature of the Earth, the value of which gets more negative as the observer ascends higher above sea level. In addition, atmospheric refraction causes celestial objects very close to the horizon to appear about half a degree higher than they would if there were no atmosphere.

See also

References

- ↑ Young, Andrew T.; Kattawar, George W.; Parviainen, Pekka (1997), "Sunset science. I. The mock mirage", Applied Optics 36 (12): 2689–2700

- ↑ Schombert, James. "Earth Coordinate System". University of Oregon Department of Physics. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ hawaii.edu

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica entry on “horizon system”