Zarrin-Kafsh

Zarrin Kafsh also Zarrinkafsh (Persian: زرین کفش, "Golden Shoe") is the name of a Persian tribe in Kordestān of Iranian ("Aryan") origin which took part in the history of the Iranian Kurdistan Province especially the city of Sanandaj under the rule of the Ardalan princes. The families of Zarrinnaal and Zarrinkafsh belong to this tribe.

History

The tribe and family of Zarrin Kafsh named to be descending from Tous-Nowzar, a mythological Persian prince and hero mentioned in Zarathustra's Holy Book Avesta as well as in Ferdowsi's "Book of Kings" Shahnameh. Tous founded with his camp the settlement of the later city of Sanandaj,[1] which became the Zarrin Kafsh tribe's fief, and then capital of the Kurdish Ardalan principality and finally of the Iranian province of Kurdistan.[2] Eleven generations followed Tous in the family tree and their names were Yawar, Kardank, Tiruyeh, Aubid (Avid), Karvan, Karen (Qaren), Veshapur, Nersi, Zahan, Veshapur and Sokhra.[3] Sokhra at least was the father of Gustaham, who was the first one called Zarrin Kafsh.

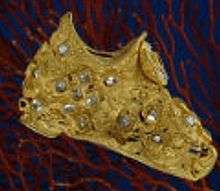

The members of this tribe wear the ‘klut’ (a distinct headgear) and the ‘shala'i’ (a black shawl), which was wrapped around the headgear in a specific way. And they wore shoes stitched with golden silk on their feet, which had been the attribute for royal ancestry. And this was the reason why that tribe was called Zarrin Kafsh i. e. “Golden Shoe”.[4] Until the first half of the 20th century the men and women of this tribe continue to wear shoes with golden silk brocade (golâbtun), symbole of royalty in ancient Persia.[5]

Parthian background

The historical pendant to the House of Tous could be found in a branch of the Parthian Arsacid Dynasty (247 BC to 224 AD), and the dispute between the royal heroes Tous and Godarz "may reflect a rivalry between two powerful Parthian noble houses".[6] Such a war of succession happened when different lines of the Arsacides (Ashkanian) struggled for becoming Great King of the Parthian Empire which was only known by later Persian historians as a kingdom of 18 "petty rulers" (Middle Persian: kadak-khvaday; Arabian: moluk al-tawa'ef).

Therefore, the figure of Tous' opponent Godarz can be identified as the historic “Satrap of Satraps” Gotarzes son of Gev, who occupied the Parthian throne as rival-king Gotarzes II (r. 40 and 45–51), when adopted as legal son by Artabanus II (r. 10-40) and ruled after him and Artabanus' native son Vardanes I (r. 40–45). Gotarzes' own rule was attacked by another Arsacid prince called Meherdates, son of Vonones I (r. 8–11) and grandson of Phraates IV (r. 37–2 BC), who became rival-king as Mithridates (VI) (r. 49–50). But at least this prince failed against Gotarzes, was deposed and mutilated.[7]

In the same way, the House of Tous finds its role model in a branch of the Parthian noble house of Karen, since in both families the very same names and persons appeared up from Karen, son of Karvan, Veshapur I, Nersi, Zahan, Veshapur II and Sokhra.

The House of Karen

The House of Karen (also Karen-Pahlavi) was an aristocratic feudal family of Hyrcania (Mid. Verkana, Pers. Gorgan, which means lit. “Land of the Wolves”), a satrapy situated on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea. The Karens are first attested in the Arsacid era and belong to the so-called Seven Parthian clans or “Seven Houses” (haft khandan), feudal families affiliated with the Parthian and later Sassanian court.[8] The seat of the house lay at Mah Nihawand, about 65 km south of Ecbatana (today Hamadan) in the province of Media. The Karenas claimed descent from Karen (Arab. Qaren), a figure of folklore and son of the equally mythical Kaveh the Blacksmith, called by Ferdowsi Qaren-e Razmzan ("Karen the Warrior") and Qaren-e Gurd ("Karen the Hero"). It is said that Karen became commander of King Manuchehr, and during the reign of King Nowzar fought against the Turanians. When Barman, the son of Visa, one of the Turanian heroes, killed the aged king Kai Kobad, Karen in revenge killed Barman. Finally Karen was one of the seven petty rulers instituted by King Goshtasp (i.e. Vishtaspa - who sometimes is identified with Hystaspes, the father of the historical Darius the Great) as ruler in Mah Nihawand.[9]

The members of the Karen clan mostly were known by their hereditary title of Karen (Qaren), not by their given names. And according to Roman, Armenian and Arabian historians the Karenas descended from the Arsacid royal stock, to be more precise from Arshavir, better known as Great King Phraates IV. The first one, known under this name was Arshavir’s son Karen-Pahlav (Arabian: Qaren al-falhawi; Persian: Qaren-e Pahlavi), meaning literally “Karen the Parthian”. He was commander under the already mentioned Arsacid king Mithridates (VI) and prevailed by Gotarzes II in 50 AD.[10]

Karen's special rivalry with Gotarzes is also an indicator to identify the Parthian Karenas with the House of Tous and its dispute with the House of Godarz. However, the two centuries following his time were the period in which historic facts were mixed with older Iranian myths and transformed into a legendary chivalresque epic in which many historical figures again were mentioned, among them the historical Karen identified as Karen son of Karvan from the House of Tous.[11]

Sassanian background

When the Persian Sassanid Ardashir I (r. 224–240) established himself as “King of Kings” (shahan-shah) meaning emperor of Iran after killing the last Parthian Artabanus IV (r. 213–224) in the Battle of Hormizdagan, the seven purportedly “Parthian” feudal aristocracies of Suren, Waraz, Aspahbadh, Spandiyadh, Mihran, Zik and the Karenas allied with the new founded Sassanian Dynasty which ruled Iran from 224 to 651 AD.[12]

While the clan of Suren were "arch-marshalls" responsible for the army commando, under the Sassanians the Karenas now were well known by name and hold the office of “arch-treasurers” in charge of the empire’s finances. Their most popular members were:

- Peroz Karen-Pahlav, who was their clan's head, strategos or satrap of Shiraz and envoy of Ardashir I to Artabanus IV.

- Ardakhshir Karen-Pahlav, who was a companion of Narseh (r. 293–302).

- Ardawan Karen-Pahlav, who was the army commander (spahbedh) of Shapur II (r. 309–379) and conquered vast territories in Iran’s north for the Sassanids.

- Karen son of Goshtasp Karen-Pahlav, who lived during the time of Yazdgerd I (r. 399–420).

- Parsi Karen-Pahlav son of Borzmehr, who lived under Bahram V (r. 420–438).

- Sokhra called "Zarmehr" was the son of Veshapur and founded a local dynasty in Northern Iran.[13]

The line of Sokhra Zarmehr

1. Sokhra Zarmehr was son of Veshapur II Karen-Pahlav and born in Shiraz, where his family resided, he became “margrave” (marzbān) of Sakastan which is today's Sistan. During the reign of Peroz (r. 459–484), Sokhra was army commander defeating the Armenians headed by Vahan in 483, and then became sometimes regent of the empire or great commander (vuzurg-framandar). After Peroz’ death in 484 AD he took residence in the northern parts of the Sassanid Empire and instituted Balash (r. 484–488) as the royal successor. Under him and his successor Kavadh (r. 488–496 and 498–531), whom he had released from prison, Sokhra Zarmehr was vicegerent of Kabul, Ghazna and Zabol, and then head of political affairs, but finally when becoming too powerful, he was betrayed by King Kavadh, overthrown and handed out to his opponent Shapur Mehran-Pahlav, who killed him on behalf of the king. Sokhra Zarmehr had two sons: Zarmehr (sometimes Borzmehr) and Qaren.[14]

1.1. Zarmehr (537–558) reinstated King Kavadh in 598, and he and his brother fought in the battle against the White Huns (Hephthalites) and supported and aided Khosrau I known as Anushirvan (r. 531–579). For their loyalty Khosrau I gave Zarmehr the fief of Zabolestan and the rulership over Gilan, where his line reigned as Persian vicegerents until 687 AD.[15]

1.2. Qaren got the area of Jebel al-Qaren or Koh-e Qaren (“Mount of Qaren”) in Mazanderan and in 565 AD was made espehbadh (hereditary governor) of Tabaristan (r. 565–602), where his line ruled as Qarenid Dynasty until the end of the ninth century.

1.2.1. Sokhra II (Arab. Sufrai) son of Qaren son of Sokhra was instituted by Khosrau I in 572 as governor of Tabaristan.[16]

Qaren II son of the Qarens (Qaren ben Qarinas al-Qarnas) finally held the troop command under Ardashir III (r. 628-629), but in 637 he fled from the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah and was defeated by the Arab Ibn Amir at Ecbatana, today Hamadan. During the Arab invasion the Karenas tried to maintain semi-independence by paying tribute to the Caliphate, and some of the lands of the Karenas appear to have remained independent until the 11th century, after which the House of Karen is no longer attested by name.[17]

Gustaham ben Ashak-e Zarrin Kafsh (lit. Gustaham son of Arsaces the Golden-Shoed, i.e. “from royal stock”) was the first historic person with the name of Zarrinkafsh. When Emperor Khosrau I Anushirvan wanted to subdue the rebellious Bahram, who fled to China, he ordered his wise vizier Buzurjmehr to send a military campaign and said: "I authorize you to appoint whomever you find worthy of leading this campaign and crushing this recreant!" Buzurjmehr chose Gustaham ben Ashak-e Zarrin Kafsh, a renowned Sassanid commander, eminent in that assembly of warriors, and had the Emperor confer upon him a robe of honor. Gustaham was sent at the head of twelve thousand fierce and sanguine troops, with a retinue of very many valiant lords and ferocious and lionhearted veterans, for the correction and chastisement of Bahram, with strict orders to exact also from Bahram an offering in the way of a fine, in addition to the four years’ tribute due in arrears, and in the event of the least show of resistance, to inflict a humiliating defeat upon him, and bring him to Ctesiphon chained and fettered. Gustaham was sternly enjoined not to depart from or mitigate those commands, and on receiving his orders, he made obedience and left for China.[18]

In Sassanid time some mounted generals (savaran) of the Persian army had golden shoes as symbol of their social rank and to distinguish from ordinary soldiers.[19] Thus, because of this royal footwear the commander Gustaham was called "Zarrin Kafsh".

Following the total defeat of the Sassanians by the Muslim Arabs at the Battle of Nihavand 642 AD and the conquest of the north-western part of the Persian province of Media with today’s Kurdistan, his family pledged allegiance to the Caliphate and could still secure some of their domains. Under the Arabs his line was called "Zarrinkafsh ben Naudharan".

Islamic time

Abu al-Fawaris Zarrinkafsh was the next historic person mentioned from the tribe of Zarrin Kafsh. S. Blair wrote that Abu al-Fawaris was a local notable in charge of accounts when the Seljuqs ruled Iran and in the 1090s he was that person who supervised the building work of Shiite tombs built by Majd ol-Molk in the city of Rayy.[20] And H. Kariman added that this Abu al-Fawaris was named Zarrin-kafsh.[21] Old Rayy belongs today to Tehran and was the ancient city of Raga in the former Persian province of Media. In 1117 AD the western part of Media was named Kurdistan, the land of the Kurds. The Seljuq administration divided the region in different Beyliks or fiefdoms ruled by a Beyg or lord. In Kordestān these beyliks were Sulaymaniyah ruled by the Baban clan, Sharazor first ruled by the Ardalan clan and Senneh (Sanandaj) ruled by the Zarrin Kafsh. When in the 16th and 17th century the Ottoman and Safavid empires struggled for superpower over Kurdistan, the Babans allied with the Turks and the Ardalans with the Persians. Thus, in 1517 the Ardalan focussed eastward, made themselves overlords over all other Kurdish tribes there and Hassanabad their capital. Finally when Hassanabad was fully destroyed by Ottoman forces in 1636 they chose Senneh (Sanandaj) as their capital, the original domain of the Zarrin Kafsh tribe. The Zarrin Kafsh were integrated into the Gorani confederacy of the Ardalan principality and their tribal chiefs known under the name Zarrinnaal became officials at the Ardalan court in charge of military administration.[22]

References

- ↑ Ayazi: A’ineh’-ye Sanandaj, 1360, p. 31.

- ↑ Ardalan: Les Kurdes Ardalân, 2004, p. 40.

- ↑ Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, p. 392.

- ↑ Ayazi: A’ineh’-ye Sanandaj, 1360, p. 31.

- ↑ Ardalan: Les Kurdes Ardalân, 2004, fn. 112.

- ↑ Yarshater: "Iranian National History", in: Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3 (1), 2003, p. 460 ff.

- ↑ Bivar: "The Political History of Iran under the Arsacids", in: Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3 (1), 2003, p. 21 ff.

- ↑ Lukonin: "Political, Social and Administrative Institutions", in: Cambridge History of Iran, 3 (2), 2003, p. 704.

- ↑ Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, p. 156.

- ↑ Discussed with further sources in: Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, p. 157; Hübschmann: Armenische Grammatik, 1972, p. 63; Bivar: "The Political History of Iran under the Arsacids", in: Cambridge History of Iran, 3 (1), 2003, p. 21 ff.

- ↑ Hübschmann: Armenische Grammatik, 1972, p. 43 ff.

- ↑ Tabari: Geschichte der Perser und Araber zur Zeit der Sassaniden, 1973, p. 437.

- ↑ Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, p. 157; Hübschmann: Armenische Grammatik, 1972, pp. 41, 45; Tabari: Geschichte der Perser und Araber zur Zeit der Sassaniden, 1973, pp. 683, 878.

- ↑ Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, p. 157, 305, 430; Tabari: Geschichte der Perser und Araber zur Zeit der Sassaniden, 1973, p. 438.

- ↑ Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, pp. 157, 383.

- ↑ Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, p. 157.

- ↑ Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, p. 157.

- ↑ Lakhnavi: "Dastan-e Amir Hamza Sahibqiran", 1855, p. 231; see also: Justi: Iranisches Namenbuch, 1963, p. 371.

- ↑ Farrokh: Sassanian Elite Cavalry, 2005, p. 19; Ferdowsi: Shahnameh, 2010, p. 112.

- ↑ Blair: The monumental inscriptions from early Islamic Iran and Transoxania, 1992, p. 186.

- ↑ Kariman: Rayy-e Bastan, Vol. 2, 1967, p. 419.

- ↑ Ardalan: Les Kurdes Ardalân, 2004, p. 12 ff.; Bruinessen: Agha, Scheich und Staat, 1989, p. 163; Zarrinnaal: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağādi-ye pedari-ye Zarrinna'al, 1967, No. 3-4.

Literature

Ardalan, Shireen: Les Kurdes Ardalân, Geuthner, Paris 2004.

Ayazi, Burhan: A’ineh’-ye Sanandaj, Amir Kabir, Tehran 1360 (1981).

Blair, Sheila S.: The monumental Inscriptions from early Islamic Iran and Transoxania, E.J. Brill, Leiden 1992.

Bivar, A.D.H.: "The Political History of Iran under the Arsacids", in: Cambridge History of Iran, edit. by Ehsan Yarshater, Vol. 3 (1), Cambridge University Press, London 2003, pp. 21–99.

Bruinessen, Martin M. van: Agha, Scheich und Staat. Politik und Gesellschaft Kurdistans, Edition Parabolis, Berlin 1989.

Farrokh, Kaveh: Sassanian Elite Cavalry. AD 224–642, Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2005.

Ferdowsi, Abul-Qasem: Shahnameh ("The Book of the Kings"), edit. by Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh, Reclam Verlag, Stuttgart 2010.

Ghalib Lakhnavi, Navab Mirza Aman Ali Khan (edit.): "Dastan-e Amir Hamza Sahibqiran", Kalkutta: Hakim Salib Press, 1855, in: The Annual of Urdu Studies, Vol. 15, edit. by Prof. M. Umar Memon, Chicago University Press, Chicago 2007, pp. 175–261.

Hübschmann, Heinrich: Armenische Grammatik: 1. Armenische Etymologie, Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 1972.

Justi, Ferdinand: Iranisches Namensbuch, Marburg 1895, reprint: Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 1963. Kariman, Hossein: Rayy-e Bastan, 2 vols., Anjoman-e Athar-e Melli, Tehran 1967.

Lukonin, Vladimir G.: "Political, Social and Administrative Institutions", in: Cambridge History of Iran, edit. by Ehsan Yarshater, Vol. 3 (2), Cambridge University Press, London 2003, pp. 681–747.

Tabari: Geschichte der Perser und Araber zur Zeit der Sassaniden: Aus der Arabischen Chronik des Tabari, trans. by Theodor Nöldeke, Brill Archive, Leiden 1973.

Yarshater, Ehsan: "Iranian National History", in: Cambridge History of Iran, edit. by Ehsan Yarshater, Vol. 3 (1), Cambridge University Press, London 2003, pp. 359–480.

Zarrinnaal, Jafar: Surat-e asāmi-ye ağādi-ye pedari-ye Zarrinna'al, Tehran 1967, No. 1-12.

External links

- http://www.zarrinkafsch-bahman.org

- http://books.google.com/books?hl=de&id=4U0fCVfM8q8C&dq=isbn%3A9789004093676&q=zarrin-kafsh#v=snippet&q=zarrin-kafsh&f=false

- http://www.urdustudies.com/pdf/15/13farooqim.pdf

- https://archive.org/stream/ArmenischeGrammatik/Armenische_Grammatik#page/n75/mode/2up/search/Karen