Yellowtail trumpeter

| Yellowtail trumpeter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Suborder: | Percoidei |

| Superfamily: | Percoidea |

| Family: | Terapontidae |

| Genus: | Amniataba |

| Species: | A. caudavittata |

| Binomial name | |

| Amniataba caudavittata (Richardson, 1844) | |

| | |

| Range of the Yellowtail trumpeter | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The yellowtail trumpeter, Amniataba caudavittata, (also known as the flagtailed terapon,[1] yellowtail grunter and yellow-tailed perch[2]) is a common species of coastal marine fish of the grunter family, Terapontidae. The yellowtail trumpeter is native to Australia and Papua New Guinea, ranging from Cape Leeuwin in Western Australia along the north coast to Bowen, Queensland,[2] and along the southern coast of Papua New Guinea.[3]

Taxonomy

The yellowtail trumpeter is one of three species in the genus Amniataba, which is one of fifteen genera in the grunter family, Terapontidae. The grunters are Perciformes in the suborder Percoidei.[4] Despite its common name, the yellowtail trumpeter has no relation to the 'true' trumpeters of the family Latridae.

The species was first described by Richardson in 1844 as Terapon caudavittatus, before he republished the species under the names Datnia caudavittata, Amphitherapon caudavittatus, and the currently accepted binomial name of Amniataba caudavittata.[3] Castelnau redescribed it once again as Therapon bostockii in 1873.[1] All names except Amniataba caudavittata are invalid under the ICZN rules.

Description

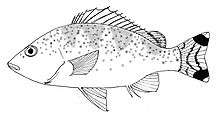

The yellowtail trumpeter can grow to a maximum length of 28 cm, but it is usually around 15 cm. The body is deep in profile and is compressed laterally. The upper jaw is slightly longer than the lower. The first gill arch has 6 to 8 gill rakers on the upper limb and 12 or 13 on the lower. The dorsal fin has 12 or 13 spines and 8 to 10 soft rays; the spinous part of the dorsal fin is curved, with the fifth spine being the longest, and the final spine the shortest. The anal fin has 3 spines and 8 or 9 soft rays, with the second anal-fin spine longer than the third, but shorter than the longest anal-fin rays. The pored scales in the lateral line number 46 to 54 with 7 to 9 rows of scales above the lateral line and 17 to 19 below it.[1]

The upper body is grey and spotted, and the lower has only light pigmentation. Some individuals have 5 or 6 incomplete vertical bars extending from around the dorsal fin to the level of the pectoral fins. The fins are generally yellow in colour, with varied dusting and blotching. The spinous dorsal fin has irregular spotting and a faint duskiness distally, but does not exhibit a distinct patch of dark pigmentation. The soft dorsal fin is dusky at the base. The spinous portion of anal fin is also slightly dusky. The caudal fin is spotted basally, with a distinct black blotch across each lobe.[1]

Habitat

The species is known to tolerate a very wide range of salinites, from fresh river waters to hypersaline waters found in some areas of Shark Bay.[5] It often inhabits estuarine waters along the Western Australian coast,[6] as well as sand and seagrass beds in inshore and offshore waters of the continental shelf.

Biology

The yellowtail trumpeter is a seasonal inhabitant of many estuaries in Western Australia, with the species most abundant in summer due to substantial recruitment of juveniles following the spawning period in early summer.[7] During colder months, it tends to move into deeper offshore waters to avoid the large influxes of fresh water entering the estuaries from upland river systems.[8]

Evidence suggests that the yellowtail trumpeter naturally hybridises with another species of freshwater terapontid, Leiopotherapon unicolor, on occasion.[9]

Diet

The fish is a benthic omnivore, preying mainly on algae, crustaceans, and polychaetes. Its diet changes with age; older fish eat more polychaetes.[8]

Life cycle

The fish usually reaches sexual maturity at the end of its second year, with some larger fish maturing after only one year. The fish spawn in estuaries. The population of the Swan River in Western Australia spawns in the upper reaches of the estuary between November and January, producing an average of 310,000 eggs in a season. The spawning period is associated with a lull in the freshwater influx of the river, resulting in fairly stable salinity and temperature regimes.[10]

The mature, unfertilised eggs of the yellowtail trumpeter are small and spherical, having an average diameter of 560 μm. The larva is pelagic and characterized by an elongate body, which becomes deeper and more laterally compressed during development.[10] The species grows seasonally, with growth only occurring in the warmer months of the year. The yellowtail trumpeter can live over 3 years.[8]

Importance to humans

The yellowtail trumpeter is of minor commercial importance throughout its range, caught with handlines, seines, and other inshore fishing gear.[1] It is not considered particularly good as food, and is considered a nuisance by many recreational fishermen who target bream in local estuaries.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carpenter, Kent E.; Volker H. Niem, eds. (2001). FAO species identification guide for fishery purposes. The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific. Volume 5. Bony fishes part 3 (Menidae to Pomacentridae) (PDF). Rome: FAO. p. 3308. ISBN 92-5-104587-9.

- 1 2 3 Hutchins, B.; Swainston, R. (1986). Sea Fishes of Southern Australia: Complete Field Guide for Anglers and Divers. Melbourne: Swainston Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 1-86252-661-3.

- 1 2 Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2007). "Amniataba caudavittata" in FishBase. September 2007 version.

- ↑ "Amniataba caudavittata". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 08 September 2007. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Molony, B.W.; G.O. Parry (2006). "Predicting and managing the effects of hypersalinity on the fish community in solar salt fields in north-western Australia". Journal of Applied Ichthyology 22 (2): 109–118. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0426.2006.00714.x.

- ↑ Potter, I.C.; Chalmer, P. N.; Tiivel, D. J.; et al. (December 2000). "The fish fauna and finfish fishery of the Leschenault Estuary in south-western Australia" (– Scholar search). Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 83 (4): 481–501. ISSN 0035-922X. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Hoeksema, S.D.; I.C. Potter (2006). "Diel, seasonal, regional and annual variations in the characteristics of the ichthyofauna of the upper reaches of a large Australian microtidal estuary". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 67 (3): 503–520. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2005.12.003.

- 1 2 3 Wise, B.S.; Potter, I. C.; Wallace, J. H (1994). "Growth, movements and diet of the terapontid Amniataba caudavittata in an Australian estuary". Journal of Fish Biology 45 (6): 917–931. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1994.tb01062.x.

- ↑ Morgan, David L.; Howard S. Gill (2006). "Osteology of the first dorsal fin in two terapontid fishes, Leiopotherapon unicolor (Gunther, 1859) and Amniataba caudavittata (Richardson, 1845), from Western Australia: evidence for hybridisation?". Records of the Western Australian Museum 23 (2): 133–144. ISSN 0312-3162.

- 1 2 Potter, I.C.; Neira, F.J.; Wise, B.S.; Wallace, J.H. (1994). "Reproductive biology and larval development of the terapontid Amniataba caudavittata, including comparisons with reproductive strategies of other estuarine teleosts in temperate western Australia". Journal of Fish Biology 45 (1): 57–74. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1994.tb01286.x.