Yangtze

| Yangtze (长江) | |

| Cháng Jiāng | |

Dusk on the middle reaches of the Yangtze River (Three Gorges) | |

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Yalong, Min, Tuo, Jialing, Han |

| - right | Wu, Yuan, Zi, Xiang, Gan, Huangpu |

| Cities | Yibin, Luzhou, Chongqing, Wanzhou, Yichang, Jingzhou, Yueyang, Wuhan, Jiujiang, Anqing, Tongling, Wuhu, Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Nantong, Shanghai |

| Source | Geladaindong Peak |

| - location | Tanggula Mountains, Qinghai |

| - elevation | 5,042 m (16,542 ft) |

| - coordinates | 33°25′44″N 91°10′57″E / 33.42889°N 91.18250°E |

| Mouth | East China Sea |

| - location | Shanghai, and Jiangsu |

| - coordinates | 31°23′37″N 121°58′59″E / 31.39361°N 121.98306°ECoordinates: 31°23′37″N 121°58′59″E / 31.39361°N 121.98306°E |

| Length | 6,300 km (3,915 mi) [1] |

| Basin | 1,808,500 km2 (698,266 sq mi) [2] |

| Discharge | |

| - average | 30,166 m3/s (1,065,302 cu ft/s) [3] |

| - max | 110,000 m3/s (3,884,613 cu ft/s) [4][5] |

| - min | 2,000 m3/s (70,629 cu ft/s) |

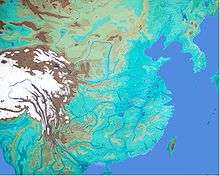

The course of the Yangtze River through China

| |

| Chang Jiang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 长江 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 長江 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "The Long River" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yangtze River | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 扬子江 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 揚子江 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | འབྲི་ཆུ་ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Yangtze River (English pronunciation: /ˈjæŋtsi/ or /ˈjɑːŋtsi/), known in China as the ![]() Cháng Jiāng (literally: "Long River") or the

Cháng Jiāng (literally: "Long River") or the ![]() Yángzǐ Jiāng, is the longest river in Asia and the third-longest in the world. It flows for 6,300 kilometers (3,915 mi) from the glaciers on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in Qinghai eastward across southwest, central and eastern China before emptying into the East China Sea at Shanghai. The river is the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It drains one-fifth of the land area of the People's Republic of China (PRC) and its river basin is home to one-third of the country's population.[6] The Yangtze is also one of the biggest rivers by discharge volume in the world.

Yángzǐ Jiāng, is the longest river in Asia and the third-longest in the world. It flows for 6,300 kilometers (3,915 mi) from the glaciers on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in Qinghai eastward across southwest, central and eastern China before emptying into the East China Sea at Shanghai. The river is the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It drains one-fifth of the land area of the People's Republic of China (PRC) and its river basin is home to one-third of the country's population.[6] The Yangtze is also one of the biggest rivers by discharge volume in the world.

The Yangtze River plays a large role in the history, culture and economy of China. The prosperous Yangtze River Delta generates as much as 20% of the PRC's GDP. The Yangtze River flows through a wide array of ecosystems and is itself habitat to several endemic and endangered species including the Chinese alligator, the finless porpoise, the Chinese paddlefish, the (possibly extinct) Yangtze River dolphin or baiji, and the Yangtze sturgeon. For thousands of years, the river has been used for water, irrigation, sanitation, transportation, industry, boundary-marking and war. The Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River is the largest hydro-electric power station in the world.[7][8]

In recent years, the river has suffered from industrial pollution, agricultural run-off, siltation, and loss of wetland and lakes, which exacerbates seasonal flooding. Some sections of the river are now protected as nature reserves. A stretch of the Yangtze flowing through deep gorges in western Yunnan is part of the Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In mid-2014 the Chinese government announced it was building a multi-tier transport network, comprising railways, roads and airports, to create a new economic belt alongside the river.[9]

Names

Chinese

Because the source of the Yangtze was not ascertained until modern times, the Chinese have given different names to lower and upstream sections of the river.[10][11]

"Yangtze" was actually the name of Chang Jiang for the lower part from Nanjing to the river mouth at Shanghai. However, due to the fact that western missionaries carried out their activities mainly in this area and were familiar with the name of this part of Chang Jiang, "Yangtze river" was used to refer to the whole Chang Jiang in English language. It should be noted that in modern Chinese, Yangtze is still used to call the lower part of Chang Jiang from Nanjing to the river mouth. Yangtze never stands for the whole Chang Jiang.

Chang Jiang – "Long River"

Chang Jiang (长江/長江) is the modern Chinese name for the lower 2,884 km (1,792 mi) of the Yangtze from its confluence with the Min River at Yibin in Sichuan Province to the river mouth at Shanghai. Chang Jiang literally means the "Long River." In antiquity, this stretch of the Yangtze was simply called Jiang 江,[12] a character that combines the water radical 氵 with the homophone 工 (now pronounced gōng, but *kˤoŋ in Old Chinese[13]). Krong was probably a word in the Austroasiatic language of local peoples such as the Yue and is similar to *krong in Proto-Vietnamese and krung in Mon, all meaning "river".[14] By the Han Dynasty, Jiang had come to mean any river in Chinese, and this river was distinguished as the "Great River" 大江 (Dàjiāng). The epithet 長 (or the simplified 长), which means "long", was first formally applied to the river during the Six Dynasties period.

Various sections of Chang Jiang have local names. From Yibin to Yichang, the river through Sichuan and Chongqing Municipality is also known as the Chuan Jiang (川江, p Chuānjiāng) or "Sichuan River." In Hubei Province, the river is also called the Jing Jiang (荆江, p Jīngjiāng) or the "Jing River" after Jingzhou. In Anhui Province, the river takes on the local name Wan Jiang after the shorthand name for Anhui, wan (皖). And Yangzi Jiang t 揚子江s 扬子江, p Yángzǐjiāng) or the "Yangzi River", from which the English name Yangtze is derived, is the local name for the Lower Yangtze in the region of Yangzhou. The name likely comes from an ancient ferry crossing called Yangzi or Yangzijin (揚子 or 揚子津, p Yángzǐ or Yángzǐjīn).[15][16][17] Europeans who arrived in the Yangtze Delta region applied this local name to the entire river.[10]

Jinsha Jiang – "Gold Sands River"

The Jinsha River (金沙江, lit. "Gold Dust"[18] or "Golden-Sanded River"[19]) is the name for 2,308 km (1,434 mi) of the Yangtze from Yibin upstream to the confluence with the Batang River near Yushu in Qinghai Province. From Antiquity until the Ming Dynasty, this stretch of the river was believed to be a tributary of the Yangtze while the Min River was thought to be the main course of the river above Yibin. In the Tribute to Yu, written in the Fifth Century BCE, this section is called the Hei Shui 黑水 or the "Black Water." The name "Jinsha" originates in the Song dynasty when the river attracted large numbers of gold prospectors. Gold prospecting along the Jinsha continues to this day.[20] Prior to the Song dynasty, other names were used including, for example Lújiāng (瀘江) from the Three Kingdoms period.[21]

Tongtian River

The Tongtian River (通天河, lit. "River Passing Through Heaven") describes the 813 km (505 mi) section from Yushu up to the confluence with the Dangqu River. The name comes from a fabled river in the Journey to the West. In antiquity, it was called the Yak River. In Mongolian, this section is known as the Murui-ussu (lit. "Winding Stream").[22] and sometimes confused with the nearby Baishui.[11]

Tuotuo River

The Tuotuo River (沱沱河, p Tuótuó Hé, lit. "Tearful River"[23] is the official headstream of the Yangtze, and flows 358 km (222 mi) from the glaciers of the Gelaindong Massif in the Tanggula Mountains of southwestern Qinghai to the confluence with the Dangqu River to form the Tongtian River.[24]) In Mongolian, this section of the river known as the Ulaan Mörön or the "Red River".

The Tuotuo one of three main headstreams of the Yangtze. The Dangqu River (当曲, p Dāngqū) is the actual geographic headwater of the Yangtze. The name is derived the Tibetan for "Marsh River" (འདམ་ཆུ, w 'Dam Chu). The Chumar River (楚玛尔河) is the Chinese name for the northern headwater of the Yangtze, which flows from the Hoh Xil Mountains in Qinghai into the Tongtian. Chumar is Tibetan for the "Red River."

English

The river was called Quian (江) and Quiansui (江水) by Marco Polo[26] and appeared on the earliest English maps as Kian or Kiam,[27][28] all recording dialects which preserved forms of the Middle Chinese pronunciation of 江 as Kæwng.[12] By the mid-19th century, these romanizations had standardized as Kiang; Dajiang, e.g., was rendered as "Ta-Kiang". "Keeang-Koo",[29] "Kyang Kew",[30] "Kian-ku",[31] and related names derived from mistaking the Chinese term for the mouth of the Yangtze (江口, p Jiāngkǒu) as the name of the river itself.

The name Blue River began to be applied in the 18th century,[27] apparently owing to a former name of the Dam Chu[32] or Min[34] and to analogy with the Yellow River,[36][37] but it was frequently explained in early English references as a 'translation' of Jiang,[38][39] Jiangkou,[29] or Yangzijiang.[40] Very common in 18th- and 19th-century sources, the name fell out of favor due to growing awareness of its lack of any connection to the river's Chinese names[19][41] and to the irony of its application to such a muddy waterway.[41][42]

The 1615 Latin account of the Jesuit missions to China included descriptions of the "Iansu" and "Iansuchian".[43] The posthumous account's translation of the name as "Son of the Ocean"[43][44] shows that Ricci, who by the end of his life was fluent in literary Chinese, was introduced to it as the homophonic 洋子江 rather than the 'proper' 揚子江. Further, although railroads and the Shanghai concessions subsequently turned it into a backwater, Yangzhou was the lower river's principal port for much of the Qing Dynasty, directing Liangjiang's important salt monopoly and connecting the Yangtze with the Grand Canal to Beijing. (That connection also made it one of the Yellow River's principal ports between the floods of 1344 and the 1850s, during which time the Yellow River ran well south of Shandong and discharged into the ocean only a few hundred kilometres away from the mouth of the Yangtze.[19][31]) By 1800, English cartographers such as Aaron Arrowsmith had adopted the French style of the name[45] as Yang-tse or Yang-tse Kiang.[46] The British diplomat Thomas Wade emended this to Yang-tzu Chiang as part of his formerly popular romanization of Chinese, based on the Beijing dialect instead of Nanjing's and first published in 1867. The spellings Yangtze and Yangtze Kiang was a compromise between the two methods adopted at the 1906 Imperial Postal Conference in Shanghai, which established postal romanization. Hanyu Pinyin was adopted by the PRC's First Congress in 1958, but it was not widely employed in English outside mainland China prior to the normalization of diplomatic relations between the United States and the PRC in 1979; since that time, the spelling Yangzi has also been used.

Tibetan

The source and upper reaches of the Yangtze are located in ethnic Tibetan areas of Qinghai.[47] In Tibetan, the Tuotuo headwaters are the Machu (རྨ་ཆུ་, w rMa-chu, lit. "Red River" or (perhaps "Wound-[like Red] River?")). The Tongtian is the Drichu (འབྲི་ཆུ་, w 'Bri Chu, lit. "River of the Female Yak"; transliterated into Chinese as 直曲, p Zhíqū).

Geography

The river originates from several tributaries, two of which have claims to be the source. The PRC government has recognized the source of the Tuotuo tributary at the base of a glacier lying on the west of Geladandong Mountain in the Dangla Mountain Range on the eastern part of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. However, the geographical source (i.e., longest river distance from the sea) lies in wetlands at 32°36′14″N 94°30′44″E / 32.60389°N 94.51222°E and 5,170 m (16,960 ft) above sea level at the head of the Dan Qu tributary.[48] These tributaries join and the river then runs eastward through Qinghai (Tsinghai), turning southward down a deep valley at the border of Sichuan (Szechwan) and Tibet to reach Yunnan. In the course of this valley, the river's elevation drops from above 5,000 m (16,000 ft) to less than 1,000 m (3,300 ft). The headwaters of the Yangtze are situated at an elevation of about 4,900 m (16,100 ft). In its descent to sea level, the river falls to an altitude of 305 m (1,001 ft) at Yibin, Sichuan, the head of navigation for riverboats, and to 192 m (630 ft) at Chongqing (Chungking). Between Chongqing and Yichang (I-ch'ang), at an altitude of 40 m (130 ft) and a distance of about 320 km (200 mi), it passes through the spectacular Yangtze Gorges, which are noted for their natural beauty but are dangerous to shipping.

It enters the basin of Sichuan at Yibin. While in the Sichuan basin, it receives several mighty tributaries, increasing its water volume significantly. It then cuts through Mount Wushan bordering Chongqing and Hubei to create the famous Three Gorges. Eastward of the Three Gorges, Yichang is the first city on the Yangtze Plain.

After entering Hubei, the Yangtze receives water from a number of lakes. The largest of these lakes is Dongting Lake, which is located on the border of Hunan and Hubei provinces, and is the outlet for most of the rivers in Hunan. At Wuhan, it receives its biggest tributary, the Han River, bringing water from its northern basin as far as Shaanxi.

At the northern tip of Jiangxi, Lake Poyang, the biggest freshwater lake in China, merges into the river. The river then runs through Anhui and Jiangsu provinces, receiving more water from innumerable smaller lakes and rivers, and finally reaches the East China Sea at Shanghai.

Four of China's five main freshwater lakes contribute their waters to the Yangtze River. Traditionally, the upstream part of the Yangtze River refers to the section from Yibin to Yichang; the middle part refers to the section from Yichang to Hukou County, where Lake Poyang meets the river; the downstream part is from Hukou to Shanghai.

The origin of the Yangtze River has been dated by some geologists to about 45 million years ago in the Eocene,[49] but this dating has been disputed. .[50]

-

The glaciers of the Tanggula Mountains, the source of the Yangtze River

-

The Tuotuo River, a headwater stream of the Yangtze River, known in Tibetan as Maqu, or the "Red River"

-

The first turn of the Yangtze at Shigu (石鼓) in Yunnan Province, where the river turns 180 degrees from south- to north-bound

-

The Jinsha River in Yunnan

-

The Tiger Leaping Gorge near Lijiang downstream from Shigu

-

Qutang Gorge, one of the Three Gorges

-

Wu Gorge, one of the Three Gorges

-

Xiling Gorge, one of the Three Gorges

Characteristics

The Yangtze flows into the East China Sea and was navigable by ocean-going vessels up 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from its mouth even before the Three Gorges Dam was built. As of June 2003, this dam spans the river, flooding Fengjie, the first of a number of towns affected by the massive flood control and power generation project. This is the largest comprehensive irrigation project in the world and has a significant impact on China's agriculture. Its proponents argue that it will free people living along the river from floods that have repeatedly threatened them in the past and will offer them electricity and water transport—though at the expense of permanently flooding many existing towns (including numerous ancient cultural relics) and causing large-scale changes in the local ecology.

Opponents of the dam point out that there are three different kinds of floods on the Yangtze River: floods which originate in the upper reaches, floods which originate in the lower reaches, and floods along the entire length of the river. They argue that the Three Gorges dam will actually make flooding in the upper reaches worse and have little or no impact on floods which originate in the lower reaches. Twelve hundred years of low water marks on the river were recorded in the inscriptions and the carvings of carp at Baiheliang, now submerged.

The Yangtze is flanked with metallurgical, power, chemical, auto, building materials and machinery industrial belts and high-tech development zones. It is playing an increasingly crucial role in the river valley's economic growth and has become a vital link for international shipping to the inland provinces. The river is a major transportation artery for China, connecting the interior with the coast.

The river is one of the world's busiest waterways. Traffic includes commercial traffic transporting bulk goods such as coal as well as manufactured goods and passengers. Cargo transportation reached 795 million tons in 2005.[51][52] River cruises several days long, especially through the beautiful and scenic Three Gorges area, are becoming popular as the tourism industry grows in China.

Flooding along the river has been a major problem. The rainy season in China is May and June in areas south of Yangtze River, and July and August in areas north of it. The huge river system receives water from both southern and northern flanks, which causes its flood season to extend from May to August. Meanwhile, the relatively dense population and rich cities along the river make the floods more deadly and costly. The most recent major floods were the 1998 Yangtze River Floods, but more disastrous were the 1954 Yangtze River Floods, killing around 30,000 people.

History

Geologic history

Although the mouth of the Yellow River has fluctuated widely north and south of the Shandong peninsula within the historical record, the Yangtze has remained largely static. Based on studies of sedimentation rates, however, it is unlikely that the present discharge site predates the late Miocene (c. 11 Ma).[53] Prior to this, its headwaters drained south into the Gulf of Tonkin along or near the course of the present Red River.[54]

Early history

The Yangtze River is important to the cultural origins of southern China. Human activity has been verified in the Three Gorges area as far back as 27,000 years ago,[55] and by the 5th millennium BC, the lower Yangtze was a major population center occupied by the Hemudu and Majiabang cultures, both among the earliest cultivators of rice. By the 3rd millennium BC, the successor Liangzhu culture showed evidence of influence from the Longshan peoples of the North China Plain.[56] A study of Liangzhu remains found a high prevalence of haplogroup O1, linking it to Austronesian and Daic populations;[57] the same study found the rare haplogroup O3d at a Daxi site on the central Yangtze, indicates possible connection with the Hmong, although "only small traces" of haplogroup O3d remains in Hmong today.[58] What is now thought of as Chinese culture developed along the more fertile Yellow River basin; the "Yue" people of the lower Yangtze possessed very different traditions – blackening their teeth, cutting their hair short, tattooing their bodies, and living in small settlements among bamboo groves[59] – and were considered barbarous by the northerners.

The Central Yangtze valley was home to sophisticated Neolithic Cultures.[60] Later on it was the earliest part of the Yangtze valley to be integrated into the North Chinese cultural sphere. North Chinese people were active there from the Bronze Age.[61]

In the lower Yangtze, two Yue tribes, the Gouwu in southern Jiangsu and the Yuyue in northern Zhejiang, display increasing Zhou (i.e., North Chinese) influence from the 9th century BC. Traditional accounts[62] credit these changes to northern refugees (Taibo and Zhongyong in Wu and Wuyi in Yue) who assumed power over the local tribes, though these are generally assumed to be myths invented to legitimate them to other Zhou rulers. As the kingdoms of Wu and Yue, they were famed as fishers, shipwrights, and sword-smiths. Adopting Chinese characters, political institutions, and military technology, they were among the most powerful states during the later Zhou. In the middle Yangtze, the state of Jing seems to have begun in the upper Han River valley a minor Zhou polity, but it adapted to native culture as it expanded south and east into the Yangtze valley. In the process, it changed its name to Chu.[63]

Whether native or nativizing, the Yangtze states held their own against the northern Chinese homeland: some lists credit them with three of the Spring and Autumn Period's Five Hegemons and one of the Warring States' Four Lords. They fell in against themselves, however. Chu's growing power led its rival Jin to support Wu as a counter. Wu successfully sacked Chu's capital Ying in 506 BC, but Chu subsequently supported Yue in its attacks against Wu's southern flank. In 473 BC, King Goujian fully annexed Wu and moved his court to its eponymous capital at modern Suzhou. In 333 BC, Chu finally united the lower Yangtze by annexing Yue, whose royal family was said to have fled south and established the Minyue kingdom in Fujian. Qin was able to unite China by first subduing Ba and Shu on the upper Yangtze in modern Sichuan, giving them a strong base to attack Chu's settlements along the river.

The state of Qin conquered the central Yangtze region, previous heartland of Chu, in 278 BC, and incorporated the region into its expanding empire. Qin then used its connections along the Yangtze River the Xiang River to expand China into Hunan, Jiangxi and Guangdong, setting up military commanderies along the main lines of communication. At the collapse of the Qin Dynasty, these southern commanderies became the independent Nanyue Empire under Zhao Tuo while Chu and Han vied with each other for control of the north.

From the Han Dynasty, the region of the Yangtze River became more and more important to China's economy. The establishment of irrigation systems (the most famous one is Dujiangyan, northwest of Chengdu, built during the Warring States period) made agriculture very stable and productive. The Qin and Han empires were actively engaged in the agricultural colonization of the Yangtze lowlands, maintaining a system of dikes to protect farmland from seasonal floods.[64] By the Song dynasty, the area along the Yangtze had become among the wealthiest and most developed parts of the country, especially in the lower reaches of the river. Early in the Qing dynasty, the region called Jiangnan (that includes the southern part of Jiangsu, the northern part of Zhejiang, and the southeastern part of Anhui) provided 1/3–1/2 of the nation's revenues.

The Yangtze has long been the backbone of China's inland water transportation system, which remained particularly important for almost two thousand years, until the construction of the national railway network during the 20th century. The Grand Canal connects the lower Yangtze with the major cities of the Jiangnan region south of the river (Wuxi, Suzhou, Hangzhou) and with northern China (all the way from Yangzhou to Beijing). The less well known ancient Lingqu Canal, connecting the upper Xiang River with the headwaters of the Guijiang, allowed a direct water connection from the Yangtze Basin to the Pearl River Delta.[65]

Historically, the Yangtze became the political boundary between north China and south China several times (see History of China) because of the difficulty of crossing the river. This occurred notably during the Southern and Northern Dynasties, and the Southern Song. Many battles took place along the river, the most famous being the Battle of Red Cliffs in 208 AD during the Three Kingdoms period.

The Yangtze was the site of naval battles between the Song dynasty and Jurchen Jin during the Jin–Song wars. In the Battle of Caishi of 1161, the ships of Emperor Hailing clashed with the Song fleet on the Yangtze. Song soldiers fired bombs of lime and sulphur using trebuchets at the Jurchen warships. The battle was a Song victory that halted the invasion by the Jin.[66][67] The Battle of Tangdao was another Yangtze naval battle from the same year.

Politically, Nanjing was the capital of China several times, although most of the time its territory only covered the southeastern part of China, such as the Wu kingdom in the Three Kingdoms period, the Eastern Jin Dynasty, and during the Southern and Northern Dynasties and Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms periods. Only the Ming occupied most parts of China from their capital at Nanjing, though it later moved the capital to Beijing. The ROC capital was located in Nanjing in the periods 1911–12, 1927–37, and 1945–49.

Age of steam

The first merchant steamer in China, the Jardine, was built to order for the firm of Jardine Matheson in 1835. She was a small vessel intended for use as a mail and passenger carrier between Lintin Island, Macao and Whampoa. However, after several trips, the Chinese authorities, for reasons best known to themselves, prohibited her entrance into the river. Lord Palmerston, the British Foreign Secretary who personified gunboat diplomacy, decided to wage war on China mainly on the "suggestions" of Jardine Matheson. In mid-1840, a large fleet of warships appeared on the China coast, and with the first cannon fire aimed at a British ship, the Royal Saxon, the British started the First Opium War. The Imperial Government, forced to surrender, gave in to the demands of the British. British military superiority was clearly evident during the armed conflict. British warships, constructed using such innovations as steam power combined with sail and the use of iron in shipbuilding, wreaked havoc on coastal towns; such ships (like the Nemesis) were not only virtually indestructible but also highly mobile and able to support a gun platform with very heavy guns. In addition, the British troops were armed with modern muskets and cannons, unlike the Qing forces. After the British took Canton, they sailed up the Yangtze and took the tax barges, a devastating blow to the Empire as it slashed the revenue of the imperial court in Beijing to just a small fraction of what it had been.

In 1842, the Qing authorities sued for peace, which concluded with the Treaty of Nanjing signed on a gunboat in the river, negotiated in August of that year and ratified in 1843. In the treaty, China was forced to pay an indemnity to Britain, open five ports to Britain, and cede Hong Kong to Queen Victoria. In the supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, the Qing empire also recognized Britain as an equal to China and gave British subjects extraterritorial privileges in treaty ports.

U.S. and French conflicts

The US, at the same time, wanting to protect its interests and expand trade, ventured the USS Wachusett six-hundred miles up the river to Hankow in about 1860, while the USS Ashuelot, a sidewheeler, made her way up the river to Yichang in 1874. The first USS Monocacy, a sidewheel gunboat, began charting the Yangtze River in 1871. The first USS Palos, an armed tug, was on Asiatic Station into 1891, cruising the Chinese and Japanese coasts, visiting the open treaty ports and making occasional voyages up the Yangtze River. From June to September 1891, anti-foreign riots up the Yangtze forced the warship to make an extended voyage as far as Hankow, 600 miles upriver. Stopping at each open treaty port, the gunboat cooperated with naval vessels of other nations and repairing damage. She then operated along the north and central China coast and on the lower Yangtze until June 1892. The cessation of bloodshed with the Taiping Rebellion, Europeans put more steamers on the river. The French engaged the Chinese in war over the rule of Vietnam. The Sino-French Wars of the 1880s emerged with the Battle of Shipu having French cruisers in the lower Yangtze.

The China Navigation Company was an early shipping company founded in 1876 in London, initially to trade up the Yangtze River from their Shanghai base with passengers and cargo. Chinese coastal trade started shortly after and in 1883 a regular service to Australia was initiated. Most of the company's ships were seized by Japan in 1941 and services did not resume until 1946. Robert Dollar was a later shipping magnate, who became enormously influential moving Californian and Canadian lumber to the Chinese and Japanese market.

Yichang, or Ichang, 1,600 km (990 mi) from the sea, is the head of navigation for river steamers; oceangoing vessels may navigate the river to Hankow, a distance of almost 1,000 km (almost 600 mi) from the sea. For about 320 km (200 mi) inland from its mouth, the river is virtually at sea level.

The Chinese Government, too, had steamers. It had its own naval fleet, the Nanyang Fleet, which fell prey to the French fleet. The Chinese would rebuild its fleet, only to be ravaged by another war with Japan (1895), Revolution (1911) and ongoing inefficiency and corruption. Chinese companies ran their own steamers, but were second tier to European operations at the time.

Navigation on the upper river

Steamers came late to the upper river, the section stretching from Yichang to Chongqing. Freshets from Himalayan snowmelt created treacherous seasonal currents. But summer was better navigationally and the three gorges, described as an "150-mile passage which is like the narrow throat of an hourglass", posed hazardous threats of crosscurrents, whirlpools and eddies, creating significant challenges to steamship efforts. Furthermore, Chongqing is 700 – 800 feet above sea level, requiring powerful engines to make the upriver climb. Junk travel accomplished the upriver feat by employing 70 - 80 trackers, men hitched to hawsers who physically pulled ships upriver through some of the most risky and deadly sections of the three gorges.[68] Achibald John Little took an interest in Upper Yangtze navigation when in 1876, the Chefoo Convention opened Chongqing to consular residence but stipulated that foreign trade might only commence once steamships had succeeded in ascending the river to that point. Little formed the Upper Yangtze Steam Navigation Co., Ltd. and built Kuling but his attempts to take the vessel further upriver than Yichang were thwarted by the Chinese who were concerned about the potential loss of transit duties, competition to their native junk trade and physical damage to their crafts caused by steamship wakes. Kuling was sold to China Merchants Steam Navigation Company for lower river service. In 1890, the Chinese government agreed to open Chongqing to foreign trade as long as it was restricted to native crafts. In 1895, the Treaty of Shimonoseki provided a provision which opened Chongqing fully to foreign trade. Little took up residence in Chongqing and built Leechuan, to tackle the gorges in 1898. In March Leechuan completed the upriver journey to Chongqing but not without the assistance of trackers. Leechuan was not designed for cargo or passengers and if Little wanted to take his vision one step further, he required an expert pilot.[69] In 1898, Little persuaded Captain Samuel Cornell Plant to come out to China to lend his expertise. Captain Plant had just completed navigation of Persia's Upper Karun River and took up Little's offer to assess the Upper Yangtze on Leechuan at the end of 1898. With Plant's design input, Little had SS Pioneer built with Plant in command. In June 1900, Plant was the first to successfully pilot a merchant steamer on the Upper Yangtze from Yichang to Chongqing. Pioneer was sold to British Royal Navy after its first run due to threat from the Boxer Rebellion and renamed HMS Kinsha. Germany's steamship effort that same year on SS Suixing ended in catastrophe. On Suixing's maiden voyage, the vessel hit a rock and sunk, killing its captain and ending realistic hopes of regular commercial steam service on the Upper Yangtze. In 1908, local Sichuan merchants and their government partnered with Captain Plant to form Sichuan Steam Navigation Company becoming the first successful service between Yichang and Chongqing. Captain Plant designed and commanded its two ships, SS Shutung and SS Shuhun. Other Chinese vessels came onto the run and by 1915, foreign ships expressed their interest too. Plant was appointed by Chinese Maritime Customs Service as First Senior River Inspector in 1915. In this role, Plant installed navigational marks and established signaling systems. He also wrote Handbook for the Guidance of Shipmasters on the Ichang-Chungking Section of the Yangtze River, a detailed and illustrated account of the Upper Yangtze's currents, rocks, and other hazards with navigational instruction. Plant trained hundreds of Chinese and foreign pilots and issued licenses and worked with the Chinese government to make the river safer in 1917 by removing some of the most difficult obstacles and threats with explosives. In August 1917, British Asiatic Petroleum became the first foreign merchant steamship on the Upper Yangtze. Commercial firms, Robert Dollar Company, Jardine Matheson, Butterfield and Swire and Standard Oil added their own steamers on the river between 1917 - 1919. Between 1918 -1919, Sichuan warlord violence and escalating civil war put Sichuan Steam Navigational Company out of business.[70] Shutung was commandeered by warlords and Shuhun was brought down river to Shanghai for safekeeping.[71] In 1921, when Captain Plant died tragically at sea while returning home to England, a Plant Memorial Fund was established to perpetuate Plant's name and contributions to Upper Yangtze navigation. The largest shipping companies in service, Butterfield & Swire, Jardine Matheson, Standard Oil, Mackenzie & Co., Asiatic Petroleum, Robert Dollar, China Merchants S.N. Co. and British-American Tobacco Co., contributed alongside international friends and Chinese pilots. In 1924, a 50-foot granite pyramidal obelisk was erected in Xintan, on the site of Captain Plant's home, in a Chinese community of pilots and junk owners. One face of the monument is inscribed in Chinese and another in English. Though recently relocated to higher ground ahead of the Three Gorges Dam, the monument still stands overlooking the Upper Yangtze River near Yichang, a rare collective tribute to a westerner in China.[72][73]

Until 1881, the India and China coastal and river services were operated by several companies. In that year, however, these were merged into the Indo-China Steam Navigation Company Ltd, a public company under the management of Jardine's. The Jardine company pushed inland up the Yangtsze River on which a specially designed fleet was built to meet all requirements of the river trade. For many years, this fleet gave unequalled service. Jardine's established an enviable reputation for the efficient handling of shipping. As a result, the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company invited the firm to attend to the Agency of their Shire Line which operated in the Far East. Standard Oil ran the tankers Mei Ping, Mei An and Mei Hsia, which were all destroyed on December 12, 1937 when Japanese warplanes bombed and sank the U.S.S. Panay. One of the Standard Oil captains who survived this attack had served on the Upper River for 14 years.[74]

Navy ships

With the Treaty Ports, the European powers and Japan were allowed to float navy ships into China's internal waters. The British, Americans and French did this. A full international fleet featured on Chinese waters: Austro-Hungarian, Portuguese, Italian, Russian and German navy ships came to Shanghai and the treaty ports. The Japanese engaged in open war with the Chinese twice, and Russians twice, over conquest of the Chinese Qing Empire—in the First and Second Sino-Japanese War 1895, and 1905; and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. Incidentally, both the French and Japanese navies were heavily involved in running opium and narcotics to Shanghai, where it was refined into morphine. It was then transhipped by liner back to Marseille and France (i.e. French Connection) for processing in Germany and eventual sale in the U.S. or Europe.

In 1909 the gunboat USS Samar changed station to Shanghai, where she regularly patrolled the lower Yangtze River up to Nanking and Wuhu. Following an anti-foreign riots in Changsha in April 1910, which destroyed a number of missions and merchant warehouses, Samar sailed up the Yangtze River to Hankow and then Changsa to show the flag and help restore order. The gunboat was also administratively assigned to the Asiatic Fleet that year, which had been reestablished by the Navy to better protect, in the words of the Bureau of Navigation, "American interests in the Orient." After returning to Shanghai in August, she sailed up river again the following summer, passing Wuhu in June but then running aground off Kichau on July 1, 1911.

After staying stuck in the mud for two weeks, Samar broke free and sailed back down river to coal ship. Returning upriver, the gunboat reached Hankow in August and Ichang in September where she wintered over owing to both the dry season and the outbreak of rebellion at Wuchang in October 1911. Tensions eased and the gunboat turned downriver in July 1912, arriving at Shanghai in October. Samar patrolled the lower Yangtze after fighting broke out in the summer 1913, a precursor to a decade of conflict between provincial warlords in China. In 1919, she was placed on the disposal list at Shanghai following a collision with a Yangtze River steamer that damaged her bow.

The Spanish boats were replaced in the 1920s by the Luzon and Mindanao were the largest, USS Oahu and Panay next in size, and Guam and Tutuila the smallest. China in the first fifty years of the 20th century, was in low-grade chaos. Warlords, revolutions, natural disasters, civil war and invasions contributed. Yangtze boats were involved in the Nanking Incident in 1927 when the Communists and Nationalists broke into open war. The Chiang Kai-shek's massacre of the Communists in Shanghai in 1927 furthered the unrest, U.S. Marines with tanks were landed. River steamers were popular targets for both Nationalists and Communists, and peasants who would take periodic pot-shots at vessels. During the course of service the second USS Palos protected American interests in China down the entire length of the Yangtze, at times convoying U.S. and foreign vessels on the river, evacuating American citizens during periods of disturbance and in general giving credible presence to U.S. consulates and residences in various Chinese cities. In the period of great unrest in central China in the 1920s, Palos was especially busy patrolling the upper Yangtze against bands of warlord soldiers and outlaws. The warship engaged in continuous patrol operations between Ichang and Chungking throughout 1923, supplying armed guards to merchant ships, and protecting Americans at Chungking while that city was under siege by a warlord army.

The British Royal Navy had a series of Insect class gunboats which patrolled between Chungking and Shanghai. Cruisers and destroyers and Fly class vessels also patrolled. The most infamous incident was when USS Panay and HMS Bee in 1937, were dive-bombed by Japanese aeroplanes during the notorious Nanking Massacre. The Westerners were forced to leave the Yangtze River with the Japanese takeover in 1941. The former steamers were either sabotaged or pressed into Japanese or Chinese service. Probably the most curious incident involved HMS Amethyst in 1949 during the Chinese Civil War between Kuomintang and People's Liberation Army forces; and led to the award of the Dickin Medal to the ship's cat Simon.

Hydrology

Periodic floods

Tens of millions of people live in the floodplain of the Yangtze valley, an area that naturally floods every summer and is habitable only because it is protected by river dikes. The floods large enough to overflow the dikes have caused great distress to those who live and farm there. Floods of note include 1931, 1935, 1954, 1998.

The 1931 Central China floods or the Central China floods of 1931 were a series of floods that occurred in the Republic of China. The floods are generally considered among the deadliest natural disasters ever recorded, and almost certainly the deadliest of the 20th century (when pandemics and famines are discounted). Estimates of the total death toll range from 145,000 to between 3.7 million and 4 million.

The Yangtze again flooded in 1935, causing great loss of life.

From June to September 1954, the Yangtze River Floods were a series of catastrophic floodings that occurred mostly in Hubei Province. Due to unusually high volume of precipitation as well as an extraordinarily long rainy season in the middle stretch of the Yangtze River late in the spring of 1954, the river started to rise above its usual level in around late June. Despite efforts to open three important flood gates to alleviate the rising water by diverting it, the flood level continued to rise until it hit the historic high of 44.67 m in Jingzhou, Hubei and 29.73 m in Wuhan. The number of dead from this flood was estimated at around 33,000, including those who died of plague in the aftermath of the disaster.

The 1998 Yangtze River floods (1998年中国洪水) was a major flood that lasted from middle of June to the beginning of September 1998 in the People's Republic of China at the Yangtze River.[75] The event was considered the worst Northern China flood in 40 years.[76] In the summer of 1998, China experienced massive flooding of parts of the Yangtze River, resulting in 3,704 dead, 15 million homeless and $26 billion in economic loss.[77] Other sources report a total loss of 4150 people, and 180 million people were affected.[76] A staggering 25 million acres (100,000 km2) were evacuated, 13.3 million houses were damaged or destroyed. The floods caused $26 billion in damages.[76]

Degradation of the river

Beginning in the 1950s dams and thousands of kilometres of dykes were built for flood control, land reclamation, irrigation and for the control of diseases vectors such as blood flukes that caused Schistosomiasis. More than a hundred lakes were thus cut off from the main river.[78] There were gates between the lakes that could be opened during floods. However, farmers and settlements encroached on the land next to the lakes although it was forbidden to settle there. When floods came, it proved impossible to open the gates since it would have caused substantial destruction.[79] Thus the lakes partially or completely dried up. For example, Baidang Lake shrunk from 100 square kilometers (39 sq mi) in the 1950s to 40 square kilometers (15 sq mi) in 2005. Zhangdu Lake dwindled to one quarter of its original size. Natural fisheries output in the two lakes declined sharply. Only a few large lakes, such as Poyang Lake and Dongting Lake, remained connected to the Yangtze. Cutting off the other lakes that had served as natural buffers for floods increased the damage done by floods further downstream. Furthermore, the natural flow of migratory fish was obstructed and biodiversity across the whole basin decreased dramatically. Intensive farming of fish in ponds spread using one type of carp who thrived in eutrophic water conditions and who feeds on algae, causing widespread pollution. The pollution was exacerbated by the discharge of waste from pig farms as well as of untreated industrial and municipal sewage.[78][80] In September 2012, the Yangzte river near Chongqing turned red from pollution.[81] The erection of the Three Gorges Dam has created an impassable "iron barrier" that has led to a great reduction in the biodiversity of the river. Yangtze sturgeon use seasonal changes in the flow of the river to signal when is it time to migrate. However, these seasonal changes will be greatly reduced by dams and diversions. Other animals facing immediate threat of extinction are the Baiji Dolphin, finless porpoise and the Yangtze Alligator. These animals numbers went into freefall from the combined effects of accidental catches during fishing, river traffic, habitat loss and pollution. In 2006 the baiji dolphin went extinct; the world lost an entire genus.[82]

Reconnecting lakes

In 2002 a pilot program was initiated to reconnect lakes to the Yangtze with the objective to increase biodiversity and to alleviate flooding. The first lakes to be reconnected in 2004 were Zhangdu Lake, Honghu Lake, and Tian'e-Zhou in Hubei province on the middle Yangtze. In 2005 Baidang Lake in Anhui Province was also reconnected.[80]

Reconnecting the lakes improved water quality and fish were able to migrate from the river into the lake, replenishing their numbers and genetic stock. The trial also showed that reconnecting the lake reduced flooding. The new approach also benefitted the farmers economically. Pond farmers switched to natural fish feed, which helped them breed better quality fish that can be sold for more, increasing their income by 30%. Based on the successful pilot project, other provincial governments emulated the experience and also reestablished connections to lakes that had previously been cut off from the river. In 2005 a Yangtze Forum has been established bringing together 13 riparian provincial governments to manage the river from source to sea.[83] In 2006 China’s Ministry of Agriculture made it a national policy to reconnect the Yangtze River with its lakes. As of 2010, provincial governments in five provinces and Shanghai set up a network of 40 effective protected areas, covering 16,500 km2 (6,400 sq mi). As a result, populations of 47 threatened species increased, including the critically endangered Yangtze alligator. In the Shanghai area, reestablished wetlands now protect drinking water sources for the city. It is envisaged to extend the network throughout the entire Yangtze to eventually cover 102 areas and 185,000 km2 (71,000 sq mi). The mayor of Wuhan announced that six huge, stagnating urban lakes including the East Lake (Wuhan) would be reconnected at the cost of US$2.3 billion creating China’s largest urban wetland landscape.[78][84]

Major cities along the river

Crossings

Until 1957, there were no bridges across the Yangtze River from Yibin to Shanghai. For millennia, travelers crossed the river by ferry. On occasions, the crossing may have been dangerous, as evidenced by the Zhong’anlun disaster (October 15, 1945).

The river stood as a major geographic barrier dividing northern and southern China. In the first half of the 20th century, rail passengers from Beijing to Guangzhou and Shanghai had to disembark, respectively, at Hanyang and Pukou, and cross the river by steam ferry before resuming journeys by train from Wuchang or Nanjing West.

After the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, Soviet engineers assisted in the design and construction of the Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge, a dual-use road-rail bridge, built from 1955 to 1957. It was the first bridge across the Yangtze River. The second bridge across the river was built a single-track railway bridge built upstream in Chongqing in 1959. The Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge, also a road-rail bridge, was the first bridge to cross the lower reaches of the Yangtze, in Nanjing. It was built after the Sino-Soviet Split and did not receive foreign assistance. Road-rail bridges were then built in Zhicheng (1971) and Chongqing (1980).

Bridge-building slowed in the 1980s before resuming in the 1990s and accelerating in the first decade of the 21st century. The Jiujiang Yangtze River Bridge was built in 1992 as part of the Beijing-Jiujiang Railway. A second bridge in Wuhan was completed in 1995. By 2005, there were a total of 56 bridges and one tunnel across the Yangtze River between Yibin and Shanghai. These include some of the longest suspension and cable-stayed bridges in the world on the Yangtze Delta: Jiangyin Suspension Bridge (1,385 m, opened in 1999), Runyang Bridge (1,490 m, opened 2005), Sutong Bridge (1,088 m, opened 2008). The rapid pace of bridge construction has continued. The city of Wuhan now has six bridges and one tunnel across the Yangtze.

A number of power line crossings have also been built across the river.

-

Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge, the first bridge crossing Yangtze, was completed in 1957.

-

The Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge, a beam bridge, was completed in 1968.

-

The Jiujiang Yangtze River Bridge, an arch bridge, was completed in 1992.

-

The Yichang Yangtze Highway Bridge, a suspension bridge near the Gezhouba Dam lock, was completed in 1996.

-

The Sutong Yangtze River Bridge, between Nantong and Suzhou, was one of the longest cable-stayed bridges in the world when it was completed in 2008.

-

The Caiyuanba Bridge, an arch bridge in Chongqing, was completed in 2007.

-

The cable-stayed Anqing Yangtze River Bridge at Anqing, was completed in 2005.

Dams

As of 2007, there are two dams built on the Yangtze river: Three Gorges Dam and Gezhouba Dam. Several dams are being constructed on the upper portion of the river, the Jinsha River.

Tributaries

The Yangtze River has over 700 tributaries. The major tributaries (listed from upstream to downstream) with the locations of where they join the Yangtze are:

- Yalong River (Panzhihua, Sichuan Province)

- Min River (Yibin, Sichuan Province)

- Tuo River (Luzhou, Sichuan Province)

- Chishui River (Southwest China)(Hejiang, Sichuan Province)

- Jialing River (Chongqing)

- Wu River (Fuling, Chongqing)

- Qing Jiang (Yidu, Hubei Province)

- Yuan River (Dongting Lake)

- Lishui River(Dongting Lake)

- Zi River(Dongting Lake)

- Xiang River (Yueyang, Hunan)

- Han River (Wuhan, Hubei)

- Gan River (near Jiujiang, Jiangxi Province.)

- Shuiyang River (Dangtu, Anhui Province)

- Qingyi River(Wuhu, Anhui Province)

- Chao Lake water system (Chaohu, Anhui Province)

- Tai Lake water system (Shanghai)

-

Lake Dongting and the Yuan, Zi, Li, and Xiang Rivers in Hunan Province

-

Jialing River in eastern Sichuan Province and Chongqing Municipality

-

Min River in central Sichuan

-

Yalong River in western Sichuan

Protected areas

- Sanjiangyuan ("Three Rivers' Sources") National Nature Reserve in Qinghai

- Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan

Wildlife

The Yangtze River has a high species richness, including many endemics, but today many of these are seriously threatened by human activities.[85]

Fish

As of 2011, 416 fish species are known from the Yangtze basin, including 362 that strictly are freshwater species. The remaining are also known from salt or brackish waters, such as the river's estuary or the East China Sea. This makes it one of the most species rich rivers in Asia and by far the most species rich in China (in comparison, the Pearl River has almost 300 fish species and the Yellow River 150).[85] 178 fish species are endemic to the Yangtze River Basin.[85] Many are only found in some section of the river basin and especially the upper reach (above Yichang, but below the headwaters in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau) is rich with 279 species, including 147 Yangtze endemics and 97 strict endemics (found only in this part of the basin). In contrast, the headwaters, where the average altitude is above 4,500 m (14,800 ft), are only home to 14 highly specialized species, but 8 of these are endemic to the river.[85] The largest orders in the Yangtze are Cypriniformes (280 species, including 150 endemics), Siluriformes (40 species, including 20 endemics), Perciformes (50 species, including 4 endemics), Tetraodontiformes (12 species, including 1 endemic) and Osmeriformes (8 species, including 1 endemic). No other order has more than four species in the river and one endemic.[85]

Many Yangtze fish species have declined drastically and 65 were recognized as threatened in the 2009 Chinese red list.[86] Among these are two that are considered entirely extinct (Anabarilius liui liui and Atrilinea macrolepis), two that are extinct in the wild (Anabarilius polylepis and Schizothorax parvus) and five that er critically endangered (Chinese paddlefish, Euchiloglanis kishinouyei, Megalobrama elongata, Schizothorax longibarbus and Leiocassis longibarbus).[86] Additionally, both the Yangtze sturgeon and Chinese sturgeon are considered critically endangered by the IUCN. The survival of these two sturgeon may rely on the continued release of captive bred specimens.[87][88] The Chinese sturgeon and Chinese paddlefish are the largest fish in the river and among the largest freshwater fish in the world, reaching lengths of 5 m (16 ft) and 7 m (23 ft) respectively.[89][90] Although listed as critically endangered rather than extinct by both the Chinese red list and IUCN, the continued survival of the Chinese paddlefish is questionable. Surveys conducted between 2006 and 2008 by ichthyologists failed to catch any, but two probable specimens were recorded with hydroacoustic signals.[91] The last definite record was a 3.6 m-long (12 ft) specimen caught during illegal fishing in 2007; despite attempts to keep it alive, it died shortly afterwards.[92]

The largest threats to the Yangtze native fish are overfishing and habitat loss (such as building of dams and land reclamation), but pollution, destructive fishing practices (such as fishing with dynamite or poison) and introduced species also cause problems.[85] About 2⁄3 of the total freshwater fisheries in China are in the Yangtze Basin,[93] but a drastic decline in size of several important species has been recorded, as highlighted by data from lakes in the river basin.[85] Some experts recommend a 10-year fishing moratorium to allow the remaining populations to recover.[94] Dams present another serious problem, as several species in the river perform breeding migrations and most of these are non-jumpers, meaning that normal fish ladders designed for salmon are ineffective.[85] For example, the Gezhouba Dam blocked the migration of the paddlerfish and two sturgeon,[87][88][90] while also effectively splitting the Chinese high fin banded shark population into two[95] and causing the extirpation of the Yangtze population of the Japanese eel.[96] In an attempt of minimizing the effect of the dams, the Three Gorges Dam has released water to mimic the (pre-dam) natural flooding and trigger the breeding of carp species downstream.[97] In addition to dams already built in the Yangtze basin, several large dams are planned and these may present further problems for the native fauna.[97]

While many fish species native to the Yangtze are seriously threatened, others have become important in fish farming and introduced widely outside their native range. A total of 26 native fish species of the Yangtze basin are farmed.[94] Among the most important are four Asian carp: grass carp, black carp, silver carp and bighead carp. Other species that support important fisheries include northern snakehead, Chinese perch, Takifugu pufferfish (mainly in the lowermost sections) and predatory carp.[85]

Other animals

Due to commercial use of the river, tourism, and pollution, the Yangtze is home to several seriously threatened species of large animals (in addition to fish): the finless porpoise, baiji (Yangtze River dolphin), Chinese alligator, Yangtze giant softshell turtle and Chinese giant salamander. This is the only other place besides the United States that is native to an alligator and paddlefish species. In 2010, the Yangtze population of finless porpoise was 1000 individuals. In December 2006, the Yangtze River dolphin was declared functionally extinct after an extensive search of the river revealed no signs of the dolphin's inhabitance.[99] In 2007, a large, white animal was sighted and photographed in the lower Yangtze and was tentatively presumed to be a baiji.[100] However, as there have been no confirmed sightings since 2004, the baiji is presumed to be functionally extinct at this time.[101] "Baijis were the last surviving species of a large lineage dating back seventy million years and one of only six species of freshwater dolphins". It has been argued that the extinction of the Yangtze River dolphin was a result of the completion of the Three Gorges Dam, a project that has affected many species of animals and plant life found only in the gorges area.[102]

Numerous species of land mammals are found in the Yangtze valley, but most of these are not directly associated with the river. Three exceptions are the semi-aquatic Eurasian otter, water deer and Père David's deer.[103]

In addition to the very large and exceptionally rare Yangtze giant softshell turtle, several smaller turtle species are found in the Yangtze basin, its delta and valleys. These include the Chinese box turtle, yellow-headed box turtle, Pan's box turtle, Yunnan box turtle, yellow pond turtle, Chinese pond turtle, Chinese stripe-necked turtle and Chinese softshell turtle, which all are considered threatened.[105]

More than 160 amphibian species are known from the Yangtze basin, including the worlds largest, the critically endangered Chinese giant salamander.[106] It has declined drastically due to hunting (it is considered a delicacy), habitat loss and pollution.[104] The polluted Dian Lake, which is part of the upper Yangtze watershed (via Pudu River), is home to several highly threatened fish, but was also home to the Yunnan lake newt. This newt has not been seen since 1979 and is considered extinct.[107][108] In contrast, the Chinese fire belly newt from the lower Yangtze basin is one of the few Chinese salamander species to remain common and it is considered Least Concern by the IUCN.[108][109][110]

The Yangtze basin contains a large number of freshwater crab species, including several endemics.[111] A particularly rich genus in the river basin is the potamid Sinopotamon.[112]

See also

- Category: Tributaries of the Yangtze River

- List of rivers in China

- Northern and Southern China, traditionally divided by the Huai River but sometimes considered to separate at the Yangtze

- South-North Water Transfer Project

- Steamboats on the Yangtze River

- Yangtze River Crossing

- Ship lifts in China

- Rediscovering the Yangtze River

- Yangtze Service Medal

References

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica: Yangtze River http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9110538/Yangtze-River

- ↑ Zhang Zengxin; Tao Hui; Zhang Qiang; Zhang Jinchi; Forher, Nicola; Hörmann, Georg. "Moisture budget variations in the Yangtze River Basin, China, and possible associations with large-scale circulation". Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment (Springer Berlin/Heidelberg) 24 (5): 579–589. doi:10.1007/s00477-009-0338-7.

- ↑ "Main Rivers". National Conditions. China.org.cn. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ↑ https://probeinternational.org/three-gorges-probe/flood-types-yangtze-river Accessed 2011-02-01

- ↑ "Three Gorges Says Yangtze River Flow Surpasses 1998". Bloomberg Businessweek. 2010-07-20. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ↑ . Accessed 10 Sept 2010. (Chinese)

- ↑ "Three Gorges Dam, China : Image of the Day". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ↑ International Rivers, Three Gorges Dam profile, Accessed August 3, 2009

- ↑ "New stimulus measures by China to boost economic growth". Beijing Bulletin. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- 1 2 Jamieson, George. Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. "Yangtsze-Kiang". Cambridge Univ. Press, 1911. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- 1 2 Yule, Henry. The River of Golden Sand: The Narrative of a Journey Through China and Eastern Tibet to Burmah, Vol. 1, p. 35. "Introductory Essay". 1880. Reprint: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- 1 2 Baxter, Wm. H. & Sagart, Laurent. Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction PDF (1.93 MB), p. 56. 2011. Accessed 12 August 2013.

- ↑ Baxter & al. (2011), p. 69 PDF (1.93 MB).

- ↑ Philipsen, Philip. Sound Business: The Reality of Chinese Characters, p. 12. iUniverse (Lincoln), 2005. Accessed 12 August 2013.

- ↑ 安民 [An Min]. 《夜晤扬子津》 ["Yangtze Ferry"]. 23 January 2010. (Chinese)

- ↑ 百度百科 [Baidu Baike]. 《扬子江》 ["Yangtze River"]. Accessed 13 August 2013. (Chinese)

- ↑ E.g., in 文天祥 [Wen Tianxiang]. 《揚子江》 ["Yangzi River"]. 1276. Accessed 13 August 2013. (Chinese)

- ↑ Little, Archibald. The Far East, p. 63. 1905. Reprint: Cambridge Univ. Press (Cambridge), 2010. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 Davis, John. The Chinese: A General Description of the Empire of China and Its Inhabitants, Vol. 1, pp. 132 ff. C. Knight, 1836.

- ↑ (Chinese) 丽江政府部门终下决心 打击金沙江非法淘金 2012-04-17

- ↑ "Baidu Baike: Lujiang". Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ Ravenstein, Ernest & al. (ed.). The Earth and Its Inhabitants, Vol. VII: "East Asia: Chinese Empire, Corea, and Japan", p. 199. D. Appleton & Co. (New York), 1884. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Powers, John & al. Historical Dictionary of Tibet, p. 155. Scarecrow Press (Plymouth), 2012. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- ↑ But note Mei Zuyan who claims the Chinese name merely transliterates a former Tibetan name.[25]

- ↑ 梅祖彦 [Mei Zuyan]. 《晚年随笔》 ["Old Age Essays"], p. 289. "The Changjiang Sanxia Hydro Power Development". 1997. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Pelliot, Paul. Notes on Marco Polo, Vol. 2, p. 818. L'Académie des Inscriptions e Belles-Lettres e avec le Concours du Centre national de la Recherche scientifique (Paris), 1959–1973. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- 1 2 E.g., Moll, Herman. "The Empire of China and island of Japan, agreeable to modern history." Bowles & Bowles (London), 1736. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, 3rd ed. "Kiam". Bell & Macfarquhar (Edinburgh), 1797. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- 1 2 Bell, James. A System of Geography, Popular and Scientific; or a Physical, Political, and Statistical Account of the World and its Various Divisions, Vol. V, Part I, p. 215. "Chinese Tartary". A. Fullarton & Co. (London), 1849. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Tanner, B. "China dividided into it's Great Provinces According to the best Authorities". Mathew Carey (Philadelphia), 1795. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- 1 2 Bridgman, Elijah (ed.) The Chinese Repository, Vol. I, pp. 37 ff. "Review. Ta Tsing Wan-neën Yih-tung King-wei Yu-too,–'A General Geographical Map, with Degrees of Latitude and Longitude, of the Empire of the Ta Tsing Dynasty–May It Last Forever', by Le Mingche Tsinglae". Canton Mission Press (Guangdong), 1833.

- ↑ Mongolian: Xөх Мөрөн, Höh or Kök Mörön.[33]

- ↑ Konstam, Angus. Yangtze River Gunboats 1900–49, p. 17. Osprey Publishing (Oxford), 2012. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Recorded as bearing the local Chinese name of 清水 (Qīngshuǐ), literally meaning "Clear Water[way]".[35]

- ↑ Davenport, Arthur. Report upon the Trading Capabilities of the Country Traversed by the Yunnan Mission, pp. 10 ff. Harrison & Sons (London), 1877.

- ↑ Aloian, Molly. Rivers Around the World: The Yangtze: China's Majestic River, p. 6. Crabtree Publishing Co. (New York), 2010. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Room, Adrian. Placenames of the World, p. 395. 1997. Reprint: McFarland (Jefferson, N.C.), 2003. Accessed 13 August 2013.

- ↑ The Modern Part of an Universal History, from the Earliest Accounts to the Present Time, Vol. XXXVII, p. 57. "Of the Empires of China and Japan". (London), 1783.

- ↑ Wilkes, John. Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, Vol. XI, p. 851. "Koko Nor". J. Adlard (London), 1812.

- ↑ Liber, Nadine. Life. "A Scary Pageant in Peking", p. 60. 4 September 1964. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- 1 2 The St. James's Magazine, Vol. XIV, p. 230. "A Cruise on the Yangtze Kyang". W. Kent & Co. (London), 1865.

- ↑ Moncrieff, A.R.H. The World of To-day: A Survey of the Lands and Peoples of The Globe as Seen in Travel and Commerce, Vol. I, p. 42. Gresham Publishing Co. (London), 1907.

- 1 2 Ricci, Matteo & al. De Christiana Expeditione apud Sinas Suscepta ab Societate Jesu, IV, pp. 365 ff. 1615. Reprint: B. Gualterus (Cologne), 1617. Accessed 14 August 2013. (Latin)

- ↑ Ricci, Matteo & al. Samuel Purchas (trans.) in Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas His Pilgrimes, Vol. XII, p. 305. "A Generall Collection and Historicall representation of the Jesuites entrance into Japon and China, untill their admission in the Royall Citie of Nanquin". 1625. Reprint: MacLehose & Co. (Glasgow), 1906. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- ↑ E.g., in Didier, Robert & al. "L'Empire de la Chine". Boudet (Paris), 1751. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Arrowsmith, Aaron. "Asia". G. Allen (London), 1801. Accessed 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Yang & al. Tibetan Geography, p. 73. China Intercontinental Press, 2004. ISBN 7-5085-0665-0.

- ↑ Wong How Man (2005) New and longer Yangtze source discovered.

- ↑ Richardson N.J.,Densmore A.L.,Seward D. Wipf M. Yong L. (2010). Did incision of the Three Gorges begin in the Eocene? Geology 38: 551-554. doi:10.1130/G30527.1

- ↑ Wang, JT; Li, CA; Yong, Y; Lei, S (2010) Detrital Zircon Geochronology and Provenance of Core Sediments in Zhoulao Town, Jianghan Plain, China. Journal of Earth Science 21 (3): 257-271.

- ↑ Xinhua - English

- ↑ Xinhua - English

- ↑ Métivier, F. & al. "Mass Accumulation Rates in Asia During the Cenozoic". Geophysical Journal International, Vol. 137, No. 2, p. 314. 1999. Accessed 5 December 2013.

- ↑ Clift, Peter. "The Marine Geological Record of Neogene Erosional in Asia: Interpreting the Sedimentary Record to Understand Tectonic and Climatic Evolution in the Wake of India-Asia Collision". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 2006. Accessed 5 December 2013.

- ↑ Nature. "Early Homo and associated artifacts from Asia".

- ↑ Chang, Kwang-chih; Goodenough, Ward H. (1996). "Archaeology of southeastern coastal China and its bearing on the Austronesian homeland". In Goodenough, Ward H. (ed.). Prehistoric settlement of the Pacific. American Philosophical Society. pp. 36–54. ISBN 978-0-87169-865-0.

- ↑ "Y chromosomes of prehistoric people along the Yangtze River.".

- ↑ Li H & al. "Y chromosomes of prehistoric people along the Yangtze River". Human Genetics, Vol. 122, No. 3–4, pp. 383–388. Nov 2007. Accessed 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Hutcheon, Robin. China-Yellow, p. 4. Chinese University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-962-201-725-2.

- ↑ Zhang Chi 張弛, “The Qujialing-Shijiahe Culture in the Middle Yangzi River Valley,” in A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, ed. Anne P. Underhill (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), 510-534; Rowan K. Flad and Pochan Chen, Ancient Central China: Centers and Peripheries along the Yangzi River (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 116–25.

- ↑ Li Liu and Xingcan Chen, State Formation in Early China (London: Duckworth, 2003), 75–79, 116–26; Li Feng, Landscape and Power in Early China: The Crisis and Fall of the Western Zhou, 1045–771 BC (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 322–32.

- ↑ For example, in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian.

- ↑ Lothar von Falkenhausen, Chinese Society in the Age of Confucius (1000–250 BC): The Archaeological Evidence (Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, 2006), 262–88; Constance A. Cook and John S. Major, eds. Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999).

- ↑ Brian Lander, “State Management of River Dikes in Early China: New Sources on the Environmental History of the Central Yangzi Region.” T’oung Pao 100.4-5 (2014): 325–362.

- ↑ Lingqu Canal (Xiang'an County, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Qin Dynasty) (Nomination for the UNESCO Heritage List)

- ↑ Tao, Jing-shen (2002). "A Tyrant on the Yangtze: The Battle of T'sai-shih in 1161". Excursions in Chinese Culture. Chinese University Press. pp. 149–155. ISBN 978-962-201-915-7.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1987). Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology: The Gunpowder Epic, Volume 5, Part 7. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- ↑ Lyman P. Van Slyke, Yangtze, Nature, History and the River, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., Massachusetts, 1988, p.18-19 and 121-123.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 170-172.

- ↑ Polly Shih Brandmeyer, "Cornell Plant, Lost Girls and Recovered Lives - Sino-British Relations at the Human Level in Late Qing and Early Republican China," Journal of Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 54 (2014), p. 106 - 110.

- ↑ "Returns of Trade and Trade Reports 1918," China - The Maritime Customs, published by Order of the Inspector General of Customs.

- ↑ Peter Simpson, "Hell and High Water," South China Morning Post Magazine, October 2, 2011, p.24-30.

- ↑ Plant Memorial Brochure, 20th March 1923, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, Archive Collection, "Papers of Capt. Samuel Cornell Plant," MS/69/123.

- ↑ Mender, P., Thirty Years A Mariner in the Far East 1907-1937, The Memoirs of Peter Mender, A Standard Oil Ship Captain on China's Yangtze River, p.53, ISBN 978-1-60910-498-6

- ↑ Chinanews.com.cn. "Chinanews.com.cn." 98年特大洪水. Retrieved on 2009-08-01.

- 1 2 3 Spignesi, Stephen J. [2004] (2004). Catastrophe!: the 100 greatest disasters of all time. Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-2558-4. p 37.

- ↑ Pbs.org. "Pbs.org." Great wall across the Yangtze. Retrieved on 2009-08-01.

- 1 2 3 WWF UK Case Study 2011 / HSBC:Safeguarding the Yangtze. Celebrating 10 years of conservation success.

- ↑ Ma, Jun (2004). "China's Water Crisis". An International Rivers Network Book. pp. 55–56.

- 1 2 China Daily (July 12, 2005). "Isolated Yangtze lakes reunited with mother river". Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ ABC News (September 7, 2012). "Yangtze River Turns Red and Turns Up a Mystery". Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ↑ Ellen Wohl. A World of Rivers, pg 287.

- ↑ WWF China. "The Yangtze Forum" (PDF). Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ WWF UK. "Where we work:China - the Yangtze". Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ye, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, J;, Zhang, T.; and Xie, S. (2011). Distribution, Endemism and Conservation Status of Fishes in the Yangtze River Basin, China. pp. 41-66 in: Ecosystems Biodiversity, InTech. ISBN 978-953-307-417-7.

- 1 2 Wang, S.; and Xie, Y. (2009). China species red list. Vol. II Vertebrates - Part 1. High Education Press, Beijing, China.

- 1 2 Qiwei, W. (2010). "Acipenser dabryanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- 1 2 Qiwei, W. (2010). "Acipenser sinensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Meadows, D.; and Coll, H. (2013). Status Review Report of Five Foreign Sturgeon. National Marine Fisheries Service, Report to Office of Protected Resources.

- 1 2 Qiwei, W. (2010). "Psephurus gladius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Zhang,; Wei1, Q.W.; Du, H.; Shen, L.; Li, Y.H.; and Zhao, Y. (2009). Is there evidence that the Chinese paddlefish (Psephurus gladius) still survives in the upper Yangtze River? Concerns inferred from hydroacoustic and capture surveys, 2006–2008. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 25(s2): 95-99. DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0426.2009.01268.x.

- ↑ Xinhua (12 January 2007). Chinese Paddlefish Dies in Illegal Fishing. CRIENGLISH.com (China Radio International). Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Liu, J.; and Cao, W. (1992). Fish resources in the Yangtze basin and the strategy for their conservation. Resources and environment in the Yangtze Valley, 1: 17-23.

- 1 2 Yiman, L.; and Zhouyang, D. (4 January 2013). Expert calls for 10-year fishing moratorium on Yangtze River. ChinaDialogue. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Zhang, C.-G.; and Zhao, Y.-H. (2001). Migration of the Chinese sucker (Myxocyprinus asiaticus) in the Yangtze River Basin with discussion on the potential effect of dams on fish. Current Zoology, 47(5): 518-521.

- ↑ Xie, P.; and Chen, Y. (1999). Threats to biodiversity in Chinese inland waters. Ambio, 28: 674-681.

- 1 2 The Nature Conservancy: China, Places We Protect: The Yangtze River. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Xing, J.H. (2010). Chinese Alligator Alligator sinensis. Pp. 5–9 in: Manolis, S.C., and Stevenson, C., eds. (2010). Crocodiles. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Third Edition. IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group: Darwin.

- ↑ "The Chinese river dolphin was functionally extinct". baiji.org. 2006-12-13. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ↑ ScienceMode " River Dolphin Thought to be Extinct Spotted Again in China

- ↑ Rare river dolphin 'now extinct'. BBC News.

- ↑ Ellen Wohl, [A World of Rivers: Environmental Changes on Ten of the World's Great Rivers], p.287.

- ↑ Smith, A.T.; and Xie, Y. (2008). A Guide to the Mammals of China. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. ISBN 978-0-691-09984-2.

- 1 2 AmphibiaWeb (2013). Andrias davidianus. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ↑ van Dijk, P.P.; Iverson, J.B.; Rhodin, A.G.J.; Shaffer, H.B.; and Bour, R. (2014). Turtles of the World, 7th Edition: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution with Maps, and Conservation Status. IUCN/SSC Turtle Taxonomy Working Group.

- ↑ WWF Global: Yangtze River. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Yang Datong, Michael Wai Neng Lau (2004). "Cynops wolterstorffi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- 1 2 Stuart, S.; Hoffman, M.; Chanson, J.; Cox, N.; Berridge, R.; Ramani, P., and Young, B. (2008). Threatened Amphibians of the World. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-96553-41-5

- ↑ Yang Datong, Michael Wai Neng Lau (2004). "Hypselotriton orientalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ AmphibiaWeb (2008). Cynops orientalis . Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Neil Cumberlidge, N.; Ng, P.K.L.; Yeo, D.C.J.; Naruse, T.; Meyer, K.S.; and Esser, L.J. (2011). Diversity, endemism and conservation of the freshwater crabs of China (Brachyura: Potamidae and Gecarcinucidae). Integrative Zoology 6(1): 45-55. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00228.x

- ↑ Fang, F.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Q.; Lin, C.; Sun, Y.; Gao, W.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J.; Ge, F.; and Liu, N. (2013). Patterns of diversity, areas of endemism, and multiple glacial refuges for freshwater crabs of the genus Sinopotamon in China (Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamidae). PLOS ONE. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053143

Further reading

- Carles, William Richard, "The Yangtse Chiang", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Sep., 1898), pp. 225–240; Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers)

- Danielson, Eric N. 2004. Nanjing and the Lower Yangzi, From Past to Present, The New Yangzi River Trilogy, Vol. II. Singapore: Times Editions/Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 981-232-598-0.

- Danielson, Eric N. 2005. The Three Gorges and The Upper Yangzi, From Past to Present, The New Yangzi River Trilogy, Vol. III. Singapore: Times Editions/Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 981-232-599-9.

- Grover, David H. 1992 American Merchant Ships on the Yangtze, 1920-1941. Wesport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers.

- Van Slyke, Lyman P. 1988. Yangtze: nature, history, and the river. A Portable Stanford Book. ISBN 0-201-08894-0

- Winchester, Simon. 1996. The River at the Center of the World: A Journey Up the Yangtze and Back in Chinese Time, Holt, Henry & Company, 1996, hardcover, ISBN 0-8050-3888-4; trade paperback, Owl Publishing, 1997, ISBN 0-8050-5508-8; trade paperback, St. Martins, 2004, 432 pages, ISBN 0-312-42337-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yangtze River (Chang Jiang). |

-

Along the Yangtze River travel guide from Wikivoyage

Along the Yangtze River travel guide from Wikivoyage -

Geographic data related to Yangtze at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Yangtze at OpenStreetMap - Yangtze Three Gorges Gallery

- Yangtze river gallery

- The Yangtse River | Vic in China: Photos and stories about the Yangtse River from families of Victoria University graduates.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|