Sycee

A sycee /saɪˈsiː/[1] was a type of silver or gold ingot currency used in China until the 20th century. The name derives from the Cantonese word meaning "fine silk"[2] (presumably Chinese: 細絲; pinyin: xìsī; Cantonese Yale: saisì), as quality silver was supposed to have a silky sheen.[3] In Chinese, they are called yuanbao (simplified Chinese: 元宝; traditional Chinese: 元寶; pinyin: yuánbǎo, abbreviation of Kaiyuan tongbao).

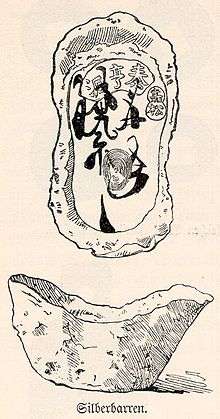

Sycee were made by individual silversmiths for local exchange; consequently, the shape and amount of extra detail on each ingot were highly variable. Square and oval shapes were common, but boat, flower, tortoise and others are known.

Sycees were not denominated or made by a central mint. Their value—like the value of the various silver coins and little pieces of silver in circulation at the end of the Qing dynasty—was determined by experienced moneyhandlers (shroffs), who estimated the appropriate discount based on the purity of the silver and evaluated the weight in taels and the progressive decimal subdivisions of the tael (mace, candareen and cash).

History

Sycees were first used as a medium for exchange as early as the Qin Dynasty (3rd century BC). During the Tang Dynasty, a standard bi-metallic system of silver and copper coinage was codified with 10 silver coins equal to 1,000 copper cash coins.[4] Tang-dynasty coins were inscribed and named Kaiyuan tongbao (開元通寶; "[era's] inaugural circulating treasures");[5][6] later abbreviated to yuan-bao, the name was applied to other non-coin forms of currency. Yuanbao was spelt yamboo[7][8] and yambu[9][10] in the 19th-century English-language literature on Xinjiang and the trade between Xinjiang and British India.

Paper money and bonds started to be used in China in the 9th century. However, due to monetary problems such as enormous local variations in monetary supply and exchange rates, rapid changes in the relative value of silver and copper, coin fraud, inflation, and political uncertainty with changing regimes, until the time of the Republic payment by weight of silver was the standard practice, and merchants carried their own scales with them. Most of the so-called "opium scales" seen in museums were actually for weighing payments in silver. The tael was still the basis of the silver currency and sycees remained in use until the end of the Qing Dynasty. Common weights were 50 taels, 10 taels, and 5 down to 1 tael.

When foreign silver coins began to circulate in China in the later 16th century, they were initially considered a type of "quasi-sycee" and imprinted with seals just as sycees were.[11]

Contemporary uses

-

Chinese New Year sycee decoration

-

Paper yuanbao burned at a grave

Today, imitation gold sycees are used a symbol of prosperity among Chinese people. They are frequently displayed during Chinese New Year, representing a fortunate year to come. Reproduction or commemorative gold sycees continue to be minted as collectibles.

Another form of imitation yuanbao – made by folding gold- or silver-colored paper – can be burned at ancestors' graves during the Ghost Festival, along with imitation paper money.

Even after currency standard changed in Republican times, the old usage of denominating value by equivalent standard weight of silver survived in Cantonese slang in the common term for a ten-cent and a five-cent piece, e.g., chat fen yi (七分二 "seven candareens, two cash") or saam fen luk (三分六 "three candareens and six cash").

See also

References

- ↑ "sycee". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) Also [more rarely spelt] sisee, seze; first attested in the early 18th century.

- ↑ Morse, Hosea Ballou. Piry, A. Théophile. [1908] (1908). The Trade and Administration of the Chinese Empire. Longmans, Green, and co publishing. Page 148. Digitized text on Google Books, no ISBN

- ↑ Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. Sungkyunkwan University, the Academy of East Asian Studies. 2008. p. 133.

In South China, a good-quality silver ingot was thought to possess a shiny veneer reminiscent of silk.

- ↑ Lockhart, James Haldane Stewart (1975). The Lockhart Collection of Chinese Copper Coins. Quarterman Publications. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-88000-056-7.

the theory is that 1000 copper cash are equal to 10 silver and 1 gold.

- ↑ Louis, François. Chinese Coins (PDF). p. 226.

- ↑ "Bronze Kaiyuan tongbao coin". Explore Highlights. British Museum.

The characters Kai yuan mean 'new beginning', while tong bao means 'circulating treasure' or 'coin'.

- ↑ Shaw, R.B. (1872–1873), "Miscellaneous notes on Eastern Turkestan", Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London (Edward Stanford) 17: 196

- ↑ Bell, James (1836), A System of Geography, Popular and Scientific: Or A Physical, Political, and Statistical Account of the World and Its Various Divisions 6, A. Fullarton and Company, p. 632

- ↑ Millward, James A. (1998), Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864, Stanford University Press, p. 62, ISBN 0804729336

- ↑ "Shoe of Gold" in Hobson-Jobson, p. 830

- ↑ Foreign Silver Coins and Chinese Sycee at Sycee-on-line.com

- Cribb, Joe. A Catalogue of Sycee in the British Museum: Chinese Silver Currency Ingots c. 1750–1933. British Museum Press, London, 1992.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sycee. |

- Examples of Chinese silver sycee (images)

- Sycee On Line

- Chinese Sycee History at Sycee-on-line.com

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||