Yajna

Yajna (IAST: yajña) literally means "sacrifice, devotion, worship, offering", and refers in Hinduism to any ritual done in front of a sacred fire, often with mantras.[1] Yajna has been a Vedic tradition, described in a layer of Vedic literature called Brahmanas, as well as Yajurveda.[2] The tradition has evolved from offering oblations and libations into sacred fire to symbolic offerings in the presence of sacred fire (Agni).[1]

Yajna rituals-related texts have been called the Karma-kanda (ritual works) portion of the Vedic literature, in contrast to Jnana-kanda (knowledge) portion contained in the Vedic Upanishads. The proper completion of Yajna-like rituals was the focus of Mimansa school of Hindu philosophy.[3] Yajna have continued to play a central role in a Hindu's rites of passage, such as weddings.[4] Modern major Hindu temple ceremonies, Hindu community celebrations, or monastic initiations may also include Yajna vedic rites, or alternatively be based on agamic rituals.

Etymology

The word yajna (Sanskrit: यज्ञ; yajña or yajJa) appears in the early Vedic literature, composed in 2nd millennium BCE.[5][6] In Rigveda, Yajurveda and others, it means "worship, devotion to anything, prayer and praise, an act of worship or devotion, a form of offering or oblation, and sacrifice".[5] In post-Vedic literature, the term meant any form of rite, ceremony or devotion with an actual or symbolic offering or effort.[5]

A Yajna included major ceremonial devotions, with or without a sacred fire, sometimes with feasts and community events. It is derived, states Nigal, from the Sanskrit verb yaj, which has a threefold meaning of worship of deities (devapujana), unity (sangatikarana) and charity (dána).[7]

The Sanskrit word is related to the Avestan term yasna of Zoroastrianism. Unlike the Vedic yajna, the Yasna is the name of a specific religious service, not a class of rituals, and they have "to do with water rather than fire".[8][9]

History

Yajna has been a part of an individual or social ritual since the Vedic times. When the ritual fire – the divine Agni, the god of fire and the messenger of gods – were deployed in a Yajna, mantras were chanted.[6] The hymns and songs sung and oblations offered into the fire were a form of hospitality for the Vedic gods.[6] The offerings were carried by Agni to the gods, the gods in return were expected to grant boons and benedictions, and thus the ritual served as a means of spiritual exchange between gods and human beings.[6]

In the Upanishadic times, or after 500 BCE, states Sikora, the meaning of the term Yajna evolved from "ritual sacrifice" performed around fires by priests, to any "personal attitude and action or knowledge" that required devotion and dedication.[6] The oldest Vedic Upanishads, such as the Chandogya Upanishad (~700 BCE) in Chapter 8, for example state,[10]

अथ यद्यज्ञ इत्याचक्षते ब्रह्मचर्यमेव

तद्ब्रह्मचर्येण ह्येव यो ज्ञाता तं

विन्दतेऽथ यदिष्टमित्याचक्षते ब्रह्मचर्यमेव

तद्ब्रह्मचर्येण ह्येवेष्ट्वात्मानमनुविन्दते ॥ १ ॥

What is commonly called Yajna is really the chaste life of the student of sacred knowledge,

for only through the chaste life of a student does he who is a knower find that,

What is commonly called Istam (sacrificial offering) is really the chaste life of the student of sacred knowledge,

for only having searched with chaste life of a student does one find Atman (Soul, Self) || 1 ||

The later Vedic Upanishads expand the idea further by suggesting that Yoga is a form of Yajna (devotion, sacrifice).[11] The Shvetashvatara Upanishad in verse 1.5.14, for example, uses the analogy of Yajna materials to explain the means to see one's soul and God, with inner rituals and without external rituals.[11][12] It states, "by making one's own body as the lower friction sticks, the syllable Om as the upper friction sticks, then practicing the friction of meditation, one may see the Deva who is hidden, as it were".[12]

Vedic practices

Vedic (Shrauta) yajnas are typically performed by four priests of the Vedic priesthood: the hotar, the adhvaryu, the udgatar and the brahmin.[13] The functions associated with the priests were:[14]

- The Hotri recites invocations and litanies drawn from the Rigveda.[15]

- The Adhvaryu is the priest's assistant and is in charge of the physical details of the ritual like measuring the ground, building the altar explained in the Yajurveda. The adhvaryu offers oblations.[15]

- The Udgatri is the chanter of hymns set to melodies and music (sāman) drawn from the Samaveda. The udgatar, like the hotar, chants the introductory, accompanying and benediction hymns.[15]

- The Brahmin is the superintendent of the entire performance, and is responsible for correcting mistakes by means of supplementary verses.

There were usually one, or three, fires lit in the center of the offering ground. Oblations are offered into the fire. Among the ingredients offered as oblations in the yajna are ghee, milk, grains, cakes and soma.[16] The duration of a yajna depends on its type, some last only a few minutes whereas, others are performed over a period of hours, days or even months. Some yajnas were performed privately, while others were community events.[16][17] In other cases, yajnas were symbolic, such as in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad hymn 3.1.6, where "the mind is the Brahmin of sacrifice" and the goal of sacrifice was complete release and liberation (moksha).[15]

The benedictions proffered ranged from long life, gaining friends, health and heaven, more prosperity, to better crops.[18][19] For example,

May my rice plants and my barley, and my beans and my sesame,

and my kidney-beans and my vetches, and my pearl millet and my proso millet,

and my sorghum and my wild rice, and my wheat and my lentils,

prosper by sacrifice (Yajna).— White Yajurveda 18.12, [20]

Yajnas, where milk products, fruits, flowers, cloth and money are offered, are called homa or havanam. A typical Hindu marriage involves a Yajna, where Agni is taken to be the witness of the marriage.[21]

Methods

_Hindu_puja%2C_yajna%2C_yagna%2C_Havanam_in_progress.jpg)

The Vedic yajna ritual is performed in modern era in a square altar called Vedi (Bedi in Nepal), set in a mandapa or mandala or kundam, wherein wood is placed along with oily seeds and other combustion aids.[22] However, in ancient times, the square principle was incorporated into grids to build large complex shapes for community events.[23] Thus a rectangle, trapezia, rhomboids or "large falcon bird" altars would be built from joining squares.[23][24] The geometric ratios of these Vedi altar, with mathematical precision and geometric theorems, are described in Shulba Sutras, one of the precursors to the development of mathematics in ancient India.[23] The offerings are called Samagri (or Yajāka, Istam). The proper methods for the rites are part of Yajurveda, but also found in Riddle Hymns (hymns of questions, followed by answers) in various Brahmanas.[22] When multiple priests are involved, they take turns as in a dramatic play, where not only are praises to gods recited or sung, but the dialogues are part of a dramatic representation and discussion of spiritual themes.[22]

The Vedic sacrifice (yajna) is presented as a kind of drama, with its actors, its dialogues, its portion to be set to music, its interludes, and its climaxes.

The Brahmodya Riddle hymns, for example, in Shatapatha Brahmana's chapter 13.2.6, is a yajna dialogue between a Hotri priest and a Brahmin priest, which would be played out during the yajna ritual before the attending audience.

Who is that is born again?

It is the moon that is born again.

And what is the great vessel?

The great vessel, doubtless, is this world.

Who was the smooth one?

The smooth one, doubtless, was the beauty (Sri, Lakshmi).

What is the remedy for cold?

The remedy for cold, doubtless, is fire.— Shatapatha Brahmana, 13.2.6.10-18[25]

Yajna during weddings

Agni and yajna play a central role in Hindu weddings. Various mutual promises between the bride and groom are made in front of the fire, and the marriage is completed by actual or symbolic walk around the fire. The wedding ritual of Panigrahana, for example, is the 'holding the hand' ritual[26] as a symbol of their impending marital union, and the groom announcing his acceptance of responsibility to four deities: Bhaga signifying wealth, Aryama signifying heavens/milky way, Savita signifying radiance/new beginning, and Purandhi signifying wisdom. The groom faces west, while the bride sits in front of him with her face to the east, he holds her hand while the Rig vedic mantra is recited in the presence of fire.[4][27]

The Saptapadi (Sanskrit for seven steps/feet), is the most important ritual in Hindu weddings, and represents the legal part of Hindu marriage.[28] The couple getting married walk around the Holy Fire (Agni), and the yajna fire is considered a witness to the vows they make to each other.[29] In some regions, a piece of clothing or sashes worn by the bride and groom are tied together for this ceremony. Each circuit around the fire is led by either the bride or the groom, varying by community and region. Usually, the bride leads the groom in the first circuit. The first six circuits are led by the bride, and the final one by the groom.[30] With each circuit, the couple makes a specific vow to establish some aspect of a happy relationship and household for each other. The fire altar or the Yajna Kunda is square.

Types

Kalpa Sutras lists the following yajna types:[31]

- The Pakayajnas — They are the aṣtaka, sthālipāka, parvana, srāvaṇi, āgrahayani, caitri and āsvīyuji. These yajnas involve consecrating cooked items.

- Soma Yajnas — Agnistoma, atyagnistoma, uktya, shodasi, vājapeya, atirātra and aptoryama are the Soma Yajnas.

- Havir Yajnas — They are the agniyādhāna, agni hotra, Darśa-Pūrṇamāsa, āgrayana, cāturmāsya, niruudha paśu bandha, sautrāmaṇi. These involve offering havis or oblations.

- The five panca mahā Yajñās, which are mentioned below.

- Vedavratas, which are four in number, done during Vedic education.

- The remaining sixteen Yajnas, which are one-time samskāras or "rituals with mantras", are Sanskara (rite of passage): garbhādhānā, pumsavana, sīmanta, jātakarma, nāmakaraṇa, annaprāśana, chudākarma/caula, niskramana, karnavedha, vidyaarambha, upanayana, keshanta, snātaka and vivāha, nisheka, antyeshti. These are specified by the gṛhya sūtrās.

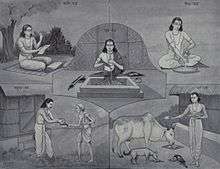

Pancha Mahayajnas

The Yajurveda describes five great Yajnas or the Pancha Mahayajnas (Taittiriya Shakha 2.10 of the Krishna Yajurveda) for an individual:[32]

- Brahmayajna — study of scriptures, learning and self-development; and teaching others. This is the most important yajna.

- Devayajna — Meditation during sandhyavandanam, praying and worship of the devas by pouring oblations into the sacred fire.

- Pitriyajna — offering tarpana libations in respect and gratitude to ancestors or pitrs.

- Manushyayajna — Caring for, looking after and feeding fellow humans.

- Bhutayajna — Caring for nature and all life. Cows, ants and birds are commonly fed.

The rituals pertaining to the three Śrautagnis are described in the Śrauta Sutras. Their performers are called Śrautins. Fourteen of the 21 compulsory yajnas are performed in the Śrautagnis. They are called Garhapatya, Ahavaniya and Dakshinagni and collectively called the tretagni.[33]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 SG Nigal (1986), Axiological Approach to the Vedas, Northern Book, ISBN 978-8185119182, pages 80-81

- ↑ Laurie Patton (2005), The Hindu World (Editors: Sushil Mittal, Gene Thursby), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772273, pages 38-39

- ↑ Randall Collins (1998), The Sociology of Philosophies, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674001879, page 248

- 1 2 Hindu Saṁskāras: Socio-religious Study of the Hindu Sacraments, Rajbali Pandey (1969), see Chapter VIII, ISBN 978-8120803961, pages 153-233

- 1 2 3 Monier Monier-Williams, Sanskrit English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-8120831056 (Reprinted in 2011), pages 839-840

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jack Sikora (2002), Religions of India, iUniverse, ISBN 978-0595247127, page 86

- ↑ Nigal, p. 81.

- ↑ Drower, 1944:78

- ↑ Boyce, 1975:147-191

- 1 2 Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 8.5.1, Oxford University Press, page 266

- 1 2 3 Jack Sikora (2002), Religions of India, iUniverse, ISBN 978-0595247127, page 87

- 1 2 Robert Hume, Shvetashvatara Upanishad 1.5.14, Oxford University Press, page 396

- ↑ Mahendra Kulasrestha (2007), The Golden Book of Upanishads, Lotus, ISBN 978-8183820127, page 21

- ↑ Nigal, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 Robert Hume, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 3.1, Oxford University Press, pages 107- 109

- 1 2 Ralph Griffith, The texts of the white Yajurveda EJ Lazarus, page i-xvi, 87-171, 205-234

- ↑ Frits Staal (2009), Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights, Penguin, ISBN 978-0143099864, page 124

- ↑ Michael Witzel (2003), "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism (Editor: Gavin Flood), Blackwell, ISBN 0-631215352, pages 76-77

- ↑ Frits Staal (2009), Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights, Penguin, ISBN 978-0143099864, pages 127-128

- ↑ Ralph Griffith, The texts of the white Yajurveda EJ Lazarus, page 163

- ↑ Hazen, Walter. Inside Hinduism. Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 9780787705862. P. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 ML Varadpande, History of Indian Theatre, Volume 1, Abhinav, ISBN , pages 45-47

- 1 2 3 Kim Plofker (2009), Mathematics in India, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691120676, pages 16-27

- ↑ Ralph Griffith, The texts of the white Yajurveda EJ Lazarus, pages 87-171

- ↑ ML Varadpande, History of Indian Theatre, Volume 1, Abhinav, ISBN , page 48

- ↑ The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M, James G. Lochtefeld (2001), ISBN 978-0823931798, Page 427

- ↑ P.H. Prabhu (2011), Hindu Social Organization, ISBN 978-8171542062, see pages 164-165

- ↑ BBC News article on Hinduism & Weddings, Nawal Prinja (August 24, 2009)

- ↑ Shivendra Kumar Sinha (2008), Basics of Hinduism, Unicorn Books, ISBN 81-7806-155-4,

The two rake the holy vow in the presence of Agni ... In the first four rounds, the bride leads and the groom follows, and in the final three, the groom leads and the bride follows. While walking around the fire, the bride places her right palm on the groom's right palm and the bride's brother pours some unhusked rice or barley into their hands and they offer it to the fire ...

- ↑ Office of the Registrar General, Government of India (1962), Census of India, 1961, v. 20, pt. 6, no. 2, Manager of Publications, Government of India,

The bride leads in all the first six pheras but follows the bridegroom on the seventh

- ↑ Prasoon, Ch.2, Vedang, Kalp.

- 1 2 Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam, ed. India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 79.

- ↑ Agrawala, p. 372.

References

- Agrawala, Vasudeva Sharana. India as known to Pāṇini: a study of the cultural material in the Ashṭādhyāyī. Prithvi Prakashan, 1963.

- Dallapiccola Anna. Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend. ISBN 0-500-51088-1.

- Gyanshruti; Srividyananda. Yajna A Comprehensive Survey. Yoga Publications Trust, Munger, Bihar, India; 1st edition (December 1, 2006). ISBN 8186336478.

- Krishnananda (Swami). A Short History of Religious and Philosophic Thought in India. Divine Life Society, Rishikesh.

- Nigal, S.G. Axiological Approach to the Vedas. Northern Book Centre, 1986. ISBN 81-85119-18-X.

- Prasoon, (Prof.) Shrikant. Indian Scriptures. Pustak Mahal (August 11, 2010). ISBN 978-81-223-1007-8.

- Vedananda (Swami). Aum Hindutvam: (daily Religious Rites of the Hindus). Motilal Banarsidass, 1993. ISBN 81-20810-81-3.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

_Hindu_wedding%2C_Saptapadi_ritual_before_Agni_Yajna.jpg)