Wuhan

| Wuhan 武汉市 | |

|---|---|

| Sub-provincial city | |

|

From top: Wuhan and the Yangtze River, Yellow Crane Tower, Wuhan Custom House, and Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge | |

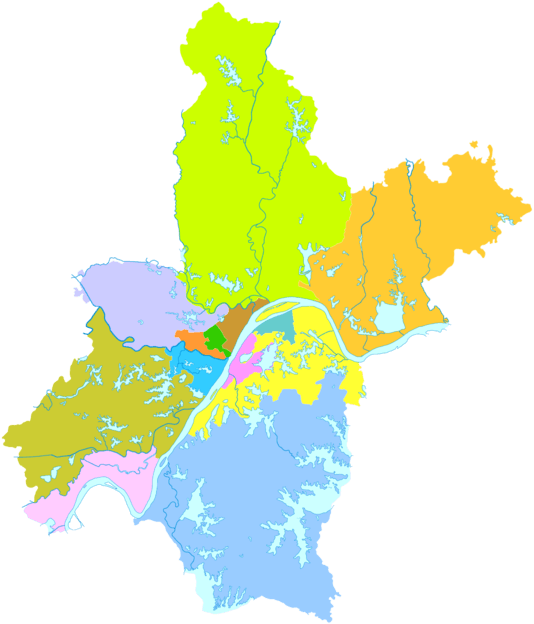

Location of Wuhan City jurisdiction in Hubei | |

Wuhan Location in China | |

| Coordinates: 30°35′N 114°17′E / 30.583°N 114.283°ECoordinates: 30°35′N 114°17′E / 30.583°N 114.283°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Hubei |

| County-level divisions | 13 |

| Township divisions | 153 |

| Settled | 1500 BC |

| Government | |

| • Party Secretary | Ruan Chengfa |

| • Mayor | Wan Yong (万勇) |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 8,494.41 km2 (3,279.71 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 37 m (121 ft) |

| Population (2013)[2] | |

| • Total | 10,220,000 |

| • Density | 1,200/km2 (3,100/sq mi) |

| 2013 | |

| Time zone | China Standard (UTC+8) |

| Postal code | 430000–430400 |

| Area code(s) | 0027 |

| GDP[3] | 2014 |

| - Total |

CNY 1.01 trillion USD 161 billion (8th) |

| - Per capita |

CNY 98,527 USD 15,764(nominal) 28,718(ppp) (11th) |

| - Growth |

|

| License plate prefixes |

鄂A 鄂O (police and authorities) |

| City trees | metasequoia |

| City flowers | plum blossom |

| Website |

www |

| Wuhan | |||||||||||||||||||

|

"Wuhan" in simplified and traditional characters | |||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Wǔhàn | ||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Wuhan | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Wu[chang] and Han[kou]" | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Wuhan is the capital of Hubei province,[4] China, and is the most populous city in Central China.[5] It lies in the eastern Jianghan Plain at the intersection of the middle reaches of the Yangtze and Han rivers. Arising out of the conglomeration of three cities, Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang, Wuhan is known as "Jiusheng Tongqu (the nine provinces' leading thoroughfare)"; it is a major transportation hub, with dozens of railways, roads and expressways passing through the city and connecting to major cities in Mainland China. Because of its key role in domestic transportation, Wuhan was sometimes referred to as the "Chicago of China."[6][7]

Holding sub-provincial status,[8] Wuhan is recognized as the political, economic, financial, cultural, educational and transportation center of central China.[5] The city of Wuhan, first termed as such in 1927, has a population of 10,220,000 people (as of 2013).[2] In the 1920s, Wuhan was the national capital of a leftist Kuomintang (KMT) government led by Wang Jingwei in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek,[9] as well as wartime capital in 1937.[10][11] At the 2010 census, its built-up (or metro) area made of 8 out of 10 urban districts (all but Xinzhou and Hannan not yet conurbated) was home to 8,821,658 inhabitants.[12]

History

With a 3,500-year-long history, Wuhan is one of the most ancient and civilized metropolitan cities in China. During the Han dynasty, Hanyang became a fairly busy port. In the winter of 208/9, one of the most famous battles in Chinese history and a central event in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms—the Battle of Red Cliffs—took place in the vicinity of the cliffs near Wuhan.[13] Around that time, walls were built to protect Hanyang (AD 206) and Wuchang (AD 223). The latter event marks the foundation of Wuhan. In AD 223, the Yellow Crane Tower (黄鹤楼) was constructed on the Wuchang side of the Yangtze River. Cui Hao, a celebrated poet of the Tang dynasty, visited the building in the early 8th century; his poem made it the most celebrated building in southern China.[14] The city has long been renowned as a center for the arts (especially poetry) and for intellectual studies. Under the Mongol rulers (Yuan dynasty), Wuchang was promoted to the status of provincial capital; by the dawn of the 18th century, Hankou had become one of China's top four most important towns of trade.

In the late 19th century, railroads were extended on a north–south axis through the city, making Wuhan an important transshipment point between rail and river traffic. Also during this period foreign powers extracted mercantile concessions, with the riverfront of Hankou being divided up into foreign-controlled merchant districts. These districts contained trading firm offices, warehouses, and docking facilities.

On October 10, 1911, Sun Yat-sen's followers launched the Wuchang Uprising,[15] which led to the collapse of the Qing dynasty,[16] as well as the establishment of the Republic of China.[17] Wuhan was the capital of a leftist Kuomintang government led by Wang Jingwei, in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek during the 1920s.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War and following the fall of Nanking in December 1937, Wuhan had become the provisional capital of China's Kuomintang government, and became another focal point of pitched air battles beginning in early 1938 between modern monoplane bomber and fighter aircraft of the Imperial Japanese forces and the Chinese Air Force, which included support from the Soviet Volunteer Group in both planes and personnel, as U.S. support in war materials waned.[18] As the battle raged on through 1938, Wuhan and the surrounding region had become the site of the Battle of Wuhan. After being taken by the Japanese in late 1938, Wuhan became a major Japanese logistics center for operations in southern China. In December 1944, the city was largely destroyed by U.S. firebombing raids conducted by the Fourteenth Air Force. In 1967, civil strife struck the city in the Wuhan Incident as a result of tensions arising out of the Cultural Revolution.

The city has been subject to devastating floods, which are now supposed to be controlled by the ambitious Three Gorges Dam, a project which was completed in 2008.

Opening Hankou as a trading port

During the Second Opium War (known in the West as the Arrow War, 1856–1860), the government of the Qing dynasty was defeated by the western powers and signed the Treaties of Tianjin and the Convention of Peking, which stipulated eleven cities or regions (including Hankou) as trading ports. In December 1858, James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin, High Commissioner to China, led four warships up the Yangtze River in Wuhan to collect the information needed for opening the trading port in Wuhan. And in the spring of 1861, Counselor Harry Parkes and Admiral Herbert were sent to Wuhan to open a trading port. On the basis of the Convention of Peking, Harry Parkes concluded the Hankou Lend-Lease Treaty with Guan Wen, the governor-general of Hunan and Hubei. It brought an area of 30.53 square kilometres (11.79 sq mi) along the Yangtze River (from Jianghan Road to Hezuo Road today) to become a British Concession and permitted Britain to set up its consulate in the concession. Thus, Hankou became an open trading port.

Hubei under Zhang Zhidong

In 1889, Zhang Zhidong was transferred from Viceroy of Liangguang (Guangdong and Guangxi provinces) to Viceroy of Huguang (Hunan and Hubei provinces). He governed the province for 18 years, until 1907. During this period, he elucidated the theory of “Chinese learning as the basis, Western learning for application,” known as the ti-yong ideal. He set up many heavy industries, founded Hanyang Steel Plant, Daye Iron Mine, Pingxiang Coal Mine and Hubei Arsenal and set up local textile industries, boosting the flourishing modern industry in Wuhan. Meanwhile, he initiated education reform, opened dozens of modern educational organizations successively, such as Lianghu (Hunan and Hubei) Academy of Classical Learning, Civil General Institute, Military General Institute, Foreign Languages Institute and Lianghu (Hunan and Hubei) General Normal School, and selected a great many students for study overseas, which well promoted the development of China’s modern education. Furthermore, he trained a modern military and organized a modern army including a zhen and a xie (both zhen and xie are military units in the Qing dynasty) in Hubei. All of these laid a solid foundation for the modernization of Wuhan.

Wuchang Uprising

The Wuchang Uprising of October 1911, which overthrew the Qing dynasty, originated in Wuhan.[15] Before the uprising, anti-Qing secret societies were active in Wuhan. In September 1911, the outbreak of the protests in Sichuan forced the Qing authorities to send part of the New Army garrisoned in Wuhan to suppress the rebellion.[19] On September 14 the Literary Society (文學社) and the Progressive Association (共進會), two local revolutionary organizations in Hubei,[19] set up joint headquarters in Wuchang and planned for an uprising. On the morning of October 9, a bomb at the office of the political arrangement exploded prematurely and alerted local authorities.[20] The proclamation for the uprising, beadroll and the revolutionaries’ official seal fell into the hands of Rui Cheng, the governor-general of Hunan and Hubei, who demolished the uprising headquarters the same day and set out to arrest the revolutionaries listed in the beadroll.[20] This forced the revolutionaries to launch the uprising earlier than planned.[15]

On the night of October 10, the revolutionaries fired shots to signal the uprising at the engineering barracks of Hubei New Army.[15] They then led the New Army of all barracks to join the revolution.[21] Under the guidance of Wu Zhaolin, Cai Jimin and others, this revolutionary army seized the official residence of the governor and government offices.[19] Rui Cheng fled in panic into the Chu-Yu Ship. Zhang Biao, the commander of Qing army, also fled the city. On the morning of the 11th, the revolutionary army took the whole city of Wuchang, but leaders such as Jiang Yiwu and Sun Wu disappeared.[15] Thus the leaderless revolutionary army recommended Li Yuanhong, the assistant governor of Qing army, as the commander-in-chief.[22] Li founded the Hubei Military Government, proclaimed the abolition of the Qing rule in Hubei, the founding of the Republic of China and published an open telegram calling for other provinces to join the revolution.[15][19] In the next two months, fourteen other provinces would declare their independence from the Qing government.[23]

As the revolution spread to other parts of the country, the Qing government concentrated loyalist military forces to suppress the uprising in Wuhan. From October 17 to December 1, the revolutionary army and local volunteers defended the city in the Battle of Yangxia against better armed and more numerous Qing forces commanded by Yuan Shikai. Huang Xing (黃興) would arrive in Wuhan in early November to take command of the revolutionary army.[19] After fierce fighting and heavy casualties, Qing forces seized Hankou and Hanyang. But Yuan agreed to halt the advance on Wuchang and participated in peace talks, which would eventually lead to the return of Sun Yat-sen from exile, founding of the Republic of China on January 1, 1912, the abdication of the Last Emperor on February 12, and the formation of a united provisional government in the spring of 1912.[17][24] Through the Wuchang Uprising, Wuhan is known as the birthplace of the Xinhai Revolution, named after the Xinhai year on the Chinese calendar.[25] The city has several museums and memorials to the revolution and the thousands of martyrs who died defending the revolution.

National government moves its capital to Wuhan

In 1926, with the north extension of the Northern Expedition, the center of the Great Revolution shifted from the Pearl River basin to the Yangtze River basin. On November 26, the KMT Central Political Committee decided to move the capital to Wuhan. In middle December, most of the KMT central executive commissioners and national government commissioners arrived in Wuhan, set up the temporary joint conference of central executive commissioners and National Government commissioners, performed the top functions of central party headquarters and National Government, declared they would work in Wuhan on January 1, 1927, and decided to combine the towns of Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang into Wuhan City, called “Capital District”. The national government was in the Nanyang Building in Hankou, while the central party headquarters and other organizations chose their locations in Hankou or Wuchang.[9]

Battle of Wuhan

In early October 1938, Japanese troops moved east and north in the outskirts of Wuhan. As a result, numerous companies and enterprises and large amounts people had to withdraw from Wuhan to the west of Hubei and Sichuan. The KMT navy undertook the responsibility of defending the Yangtze River on patrol and covering the withdrawal. On October 24, while overseeing the waters of the Yangtze River near the town of Jinkou (Jiangxia District in Wuhan) in Wuchang, the KMT gunboat Zhongshan came up against six Japanese aircraft. Though two were eventually shot down, the Zhongshan sank with 25 casualties. Raised from the bottom of the Yangtze River in 1997, and restored at a local shipyard, the Zhongshan has been moved to a purpose-built museum in Wuhan's suburban Jiangxia District, which opened on September 26, 2011.[26]

World War II

As a key center on the Yangtze, Wuhan was an important base for Japanese operations in China. On 18 December 1944, Wuhan was bombed by 77 American Stratofortress bombers that set off a firestorm that destroyed much of the city.[27] For the next three days, Wuhan was bombed by the Americans.[27] The American bombing destroyed all of the docks and warehouses of Wuhan, plus the Japanese air bases in the city while killing thousands of Chinese civilians.[27] The attack on Wuhan helped provide the inspiration for the American fire-bombing of Japan in 1945.[27]

Completion and opening-to-traffic of the First Yangtze River Bridge

The project of building the Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge, also known as the First Yangtze River Bridge, was regarded as one of the key projects during the first five-year plan. The Engineering Bureau of the First Yangtze River Bridge, set up by the Ministry of Railway in April 1953, was responsible for the design and construction of the bridge. The document "Resolutions on Building the First Yangtze River Bridge" was passed in the 203rd conference of State Council on January 15, 1954. The technical conference on the routes of the bridge, held in Hankou on January 15, 1955, determined that the route from Tortoise Hill to Snake Hill was the best choice.

On October 25, 1955, construction began on the bridge proper. The same day in 1957, the whole project was completed and an opening-to-traffic ceremony was held on October 15. The bridge is 1,670 m (5,479.00 ft) long, of which the upper level is a highway with a width of 22.5 m (73.82 ft) and the lower level is a double-line railway with a width of 18 m (59.06 ft). The bridge proper is 1,156 m (3,792.65 ft) long with two pairs of eight piers and nine arches with a space of 128 m (419.95 ft) between each arch. The First Yangtze River Bridge united the Beijing–Hankou Railway with the Guangdong–Hankou Railway into the Beijing–Guangzhou Railway, making Wuhan a thoroughfare to nine provinces in name and in fact.

Geography

| Wuhan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wuhan is in east-central Hubei, at latitude 29° 58'–31° 22' N and longitude 113° 41'–115° 05' E, east of the Jianghan Plain, and is at the confluence of the Hanshui and Yangtze Rivers along the middle reaches of the latter.

The metropolitan area comprises three parts—Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang—commonly called the "Three Towns of Wuhan" (hence the name "Wuhan", combining "Wu" from the first city and "Han" from the other two). The consolidation of these cities occurred in 1927 and Wuhan was thereby established. The parts face each other across the rivers and are linked by bridges, including one of the first modern bridges in China, known as the "First Bridge". It is simple in terrain—low and flat in the middle and hilly in the south, with the Yangtze and Han rivers winding through the city. Wuhan occupies a land area of 8,494.41 square kilometres (3,279.71 sq mi), most of which is plain and decorated with hills and a great number of lakes and pools.

Climate

Wuhan's climate is humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa) with abundant rainfall and four distinctive seasons. Wuhan is known for its oppressively humid summers, when dewpoints can often reach 26 °C (79 °F) or more.[29] Because of its hot summer weather, Wuhan is commonly known as one of the Three Furnaces of China, along with Nanjing and Chongqing.[30] Spring and autumn are generally mild, while winter is cool with occasional snow. The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from 3.7 °C (38.7 °F) in January to 28.7 °C (83.7 °F) in July. Annual precipitation totals 1,269 millimetres (50.0 in), mainly from May to July; the annual mean temperature is 16.63 °C (61.9 °F), the frost-free period lasts 211 to 272 days. With monthly possible sunshine percentage ranging from 31 percent in March to 59 percent in August, the city proper receives 1,929 hours of bright sunshine annually. Extremes since 1951 have ranged from −18.1 °C (−1 °F) on 31 January 1977 to 39.6 °C (103 °F) on 1 August 2003 (unofficial record of 41.3 °C (106 °F) was set on 10 August 1934).[31][32]

| Climate data for Wuhan (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.5 (90.5) |

27.9 (82.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.9 (76.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

13.9 (57) |

7.6 (45.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

13.1 (55.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43.4 (1.709) |

58.7 (2.311) |

95.0 (3.74) |

131.1 (5.161) |

164.2 (6.465) |

225.0 (8.858) |

190.3 (7.492) |

111.7 (4.398) |

79.7 (3.138) |

92.0 (3.622) |

51.8 (2.039) |

26.0 (1.024) |

1,268.9 (49.957) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 9.1 | 9.5 | 13.5 | 13.0 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 11.2 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 8.0 | 6.6 | 124.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 76 | 78 | 78 | 77 | 80 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 78 | 76 | 74 | 77.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 106.5 | 102.8 | 115.5 | 151.2 | 181.4 | 179.5 | 232.1 | 241.0 | 176.7 | 161.2 | 144.3 | 136.5 | 1,928.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 33 | 33 | 31 | 39 | 43 | 43 | 54 | 59 | 48 | 46 | 45 | 43 | 43.1 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[28] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

The sub-provincial city of Wuhan has direct jurisdiction over 13 districts:

| Map | District | Chinese | Pinyin | Population (2010 census)[33] |

Area (km²)[1] | Density (/km²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Districts | 6,434,373 | 888.42 | 7,242 | |||

| Jiang'an | 江岸区 | Jiāng'àn Qū | 895,635 | 64.24 | 13,942 | |

| Jianghan | 江汉区 | Jiānghàn Qū | 683,492 | 33.43 | 20,445 | |

| Qiaokou | 硚口区 | Qiáokǒu Qū | 828,644 | 46.39 | 17,863 | |

| Hanyang | 汉阳区 | Hànyáng Qū | 792,183[34] | 108.34 | 7,312 | |

| Wuchang | 武昌区 | Wǔchāng Qū | 1,199,127 | 87.42 | 13,717 | |

| Qingshan | 青山区 | Qīngshān Qū | 485,375 | 68.40 | 7,096 | |

| Hongshan | 洪山区 | Hóngshān Qū | 1,549,917[35] | 480.20 | 3,228 | |

| Suburban and Rural Districts | 3,346,271 | 7,605.99 | 440 | |||

| Dongxihu | 东西湖区 | Dōngxīhú Qū | 451,880 | 439.19 | 1,029 | |

| Hannan | 汉南区 | Hànnán Qū | 114,970 | 287.70 | 400 | |

| Caidian | 蔡甸区 | Càidiàn Qū | 410,888 | 1,108.10 | 371 | |

| Jiangxia | 江夏区 | Jiāngxià Qū | 644,835 | 2,010.00 | 321 | |

| Huangpi | 黄陂区 | Huángpí Qū | 874,938 | 2,261.00 | 387 | |

| Xinzho | 新洲区 | Xīnzhōu Qū | 848,760 | 1,500.00 | 566 | |

| Water Region (水上地区) | 4,748 | - | - | |||

| Total | 9,785,392 | 8,494.41 | 1,152 | |||

Transportation

Bridges

Wuhan has seven bridges and one tunnel across the Yangtze River. The Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge, also called the First Bridge, was built over the Yangtze River (Chang Jiang) in 1957, carrying the railroad directly across the river between Snake Hill (on the left in the picture below) and Turtle Hill. Before this bridge was built it could take up to an entire day to barge railcars across. Including its approaches, it is 5,511 feet (1,680 m) long, and it accommodates both a double-track railway on a lower deck and a four lane roadway above. It was built with the assistance of advisers from the Soviet Union.

The Second Bridge, a cable-stayed bridge, built of pre-stressed concrete, has a central span of 400 meters; it is 4,678 meters in length (including 1,877 meters of the main bridge) and 26.5 to 33.5 meters in width. Its main bridgeheads are 90 meters high each, pulling 392 thick slanting cables together in the shape of double fans, so that the central span of the bridge is well poised on the piers and the bridge's stability and vibration resistance are ensured. With six lanes on the deck, the bridge is designed to handle 50,000 motor vehicles passing every day. The bridge was completed in 1995.

The Third Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge was completed in September 2000. Located 8.6 kilometres (5.3 miles) southwest of the First Bridge, construction of Baishazhou Bridge started in 1997. With an investment of over 1.4 billion yuan (about 170 million U.S. dollars), the bridge, which is 3,586 meters long and 26.5 meters wide, has six lanes and has a capacity of 50,000 vehicles a day. The bridge is expected to serve as a major passage for the future Wuhan Ring Road, enormously easing the city's traffic and aiding local economic development.

The Yangluo Bridge carries Wuhan's Ring Road across the Yangtze in the city's eastern suburbs (connecting the Hongshan District with the Xinzhou District). It was opened on December 26, 2007.

The Wuhan Tianxingzhou Yangtze River Bridge crosses the Yangtze in the northeastern part of the city, downstream of the Second bridge. Its name is due to the Tianxing Island (Tianxingzhou), above which it crosses the river. Built at the cost of 11 billion yuan, the 4,657-meter cable suspension bridge was opened on December 26, 2009,[36] in time for the opening of the Wuhan Railway Station. It is a combined road and rail bridge, and carries the Wuhan–Guangzhou High-Speed Railway across the river.

Railways

Presently, the city of Wuhan is served by three major railway stations: the Hankou Railway Station in Hankou, the Wuchang Railway Station in Wuchang, and the new Wuhan Railway Station, located in a newly developed area east of the East Lake (Hongshan District). As the stations are many miles apart, it is important for passengers to be aware of the particular station(s) used by a particular train.

The (original) Hankou Station was the terminus for the Jinghan Railway from Beijing, while the Wuchang Station was the terminus for the Yuehan Railway to Guangzhou. But since the construction of the First Yangtze Bridge and the linking of the two lines into the Jingguang Railway, both Hankou and Wuchang stations have been served by trains going to all directions, which contrasts with the situation in such cities as New York or Moscow, where different stations serve different directions.

With the opening of the Hefei-Wuhan high-speed railway on April 1, 2009,[37] Wuhan became served by high-speed trains with Hefei, Nanjing, and Shanghai; several trains a day now connect the city with Shanghai, getting there in under 6 hours. As of the early 2010, most of these express trains leave from the Hankou Railway Station.

In 2006, construction began on the new Wuhan Railway Station with 11 platforms, located on the northeastern outskirts of the city. In December 2009, the station was opened, as China unveiled its second high-speed train with scheduled runs from Guangzhou to Wuhan. Billed as the fastest train in the world, it can reach a speed of 394 km/h (244.82 mph). The travel time between the two cities has been reduced from ten and a half hours to just three. Later, the rail service extended north to Beijing.[38]

As of 2011, the new Wuhan Railway Station is primarily used by the Wuhan-Guangzhou high-speed trains, while most regular trains to other destinations continue to use the Hankou and Wuchang stations.

Construction work is carried out on several lines of the new Wuhan Metropolitan Area Intercity Railway, which will eventually connect Wuhan's three main rail terminals with several stations throughout the city's outer areas and farther suburbs, as well as with the nearby cities of Xianning, Huangshi, Huanggang, and Xiaogan. The first line of the system, the one to Xianning, will open at the end of 2013.

The main freight railway station and marshalling yard of the Wuhan metropolitan area is the gigantic Wuhan North Railway Station (武汉北站; 30°47′16.81″N 114°18′27.02″E / 30.7880028°N 114.3075056°E), with 112 tracks and over 650 switches. It is located in Hengdiang Subdistrict (横店街道) of Huangpi District, located 20 km (12 mi) north of the Wuhan Station and 23 km (14 mi) from Hankou Station.

Public transit

When Wuhan Metro opened in September 2004, Wuhan became the fifth Chinese city with a metro system (after Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Guangzhou).[39] The first 10.2 kilometres (6.3 mi)-long line (10 stations) is an elevated rail (and therefore called 'light rail' in Chinese terminology). It runs from Huangpu to Zongguan in the downtown area of the Hankou District, and it is the first one in the country to use a communication-based train control system (a Moving Block signalling system, provided by Alcatel). The designed minimum interval is only 90 seconds between two trains and it features driverless operation.[39] Phase 2 of this line will extend the length to 28.8 km (17.90 mi) with 26 stations in total. It plans to start revenue service on July 28, 2010.[40]

Metro Line 2 opened on December 28, 2012, extending total system length to 56.85 km (35.32 mi). This is the first Metro line crossing the Yangtze River (Chang Jiang).

Line 4 opened on December 28, 2013, connecting Wuhan Railway Station and Wuchang Railway Station. All three main railway stations of the city were connected by the metro lines. Plans also exist to extend the metro's Line 2 to Wuhan Tianhe Airport by 2015.

Airport

Opened in April 1995, Wuhan Tianhe International Airport is one of the busiest airports in central China and it is located 26 kilometres (16 mi) north of Wuhan. It has also been selected as China's fourth international hub airport after Beijing Capital International Airport, Shanghai-Pudong and Guangzhou Baiyun. A second terminal was completed in March 2008, having been started in February 2005 with an investment of CNY 3.372 billion. International flights to neighboring Asian countries have also been enhanced, including direct flights to Tokyo and Nagoya, Japan.

Highway

Tourist sites

- Wuchang has the largest lake within a city in China, the East Lake, as well as the South Lake. The east lake in Wuhan is 6 times the size of the west lake in Hangzhou. The total area is more than 80 km2 (31 sq mi) of which the lake is covering an area of 33 km2 (13 sq mi). In the spring time the shores of East Lake become a garden of flowers with the Mei blossoms as the king and the Cherry Blossom as the queen among the species. Another famous flower is the lotus. The lake has a long history and especially the Chu Kingdom is well represented around East Lake. At East Lake you find fascinating gardens like the Mei Blossom Garden, Forest of the Birds, Cherry Blossom Garden and monuments from ancient times, beautiful hills and green nature. Moreover, in the Moshan Botanic Garden there are all possible types of plum blossoms, as well as lotus flowers.

- The Hubei Provincial Museum: With over 200,000 valued artifacts, this is one of the leading museums in China. Especially the artefacts from the tomb of Marquis Yi (Zenghouyi), who lived in the 5th century B.C., is a world unique treasure. The bell chime of Zeng Hou Yi is a bronze instrument performed 2430 years ago in ancient China (Warring States Period), and was discovered in the Zenghou Yi Tomb in Lei Gutun, a place near Suizhou, Hubei province in 1978. The whole chime weighs 5 tons, can perfectly play sound which was heard 2430 years ago, and was considered "The Eighth Wonder of the World".

- The Rock and Bonsai Museum includes a mounted platybelodon skeleton, many unique stones, a quartz crystal the size of an automobile, and an outdoor garden with miniature trees in the penjing ("Chinese Bonsai") style.

- Jiqing Street (吉庆街) holds many roadside restaurants and street performers during the evening, and is the site of a Live Show with stories of events on this street by contemporary writer Chi Li.

- The Lute Platform in Hanyang was where the legendary musician Yu Boya is said to have played. This is the birthplace of the renowned legend of seeking a soul mate through “high mountains and flowing water”. According to the story of 知音 (zhi yin, "understanding music"), Yu Boya played for the last time over the grave of his friend Zhong Ziqi, then smashed his lute because the only person able to appreciate his music was dead.[41]

- Some luxury riverboat tours begin here after a flight from Beijing or Shanghai, with several days of flatland cruising and then climbing through the Three Gorges with passage upstream past the Gezhouba and Three Gorges dams to the city of Chongqing. With the completion of the dam a number of cruises now start from the upstream side and continue west, with tourists traveling by motor coach from Wuhan.

- The Yellow Crane Tower (Huanghelou) is presumed to have been first built in approximately 220 AD. The tower has been destroyed and reconstructed numerous times, and was burned last according to some sources in 1884. The tower underwent complete reconstruction in 1981. The reconstruction utilized modern materials and added an elevator, while maintaining the traditional design in the tower's outward appearance.

- Happy Valley Wuhan amusement park, opened in 2012.

- Chu River and Han Street, a popular shopping district located in Wuchang with many tourist attractions, including Han Show theater, Madame Tussauds, and Movie Culture Park, etc. This project was initiated as a water connecting channel between East Lake and Shahu Lake.

- Wuhan, capital city of the Hubei Province, is a popular shopping and culinary tourist destination for both Chinese nationals and overseas visitors.

Economy

Wuhan is a sub-provincial city. In 2012, the city's GDP exceeded 800 billion CNY, growing at an annual rate of 11.4 percent. GDP is split almost evenly between the city's industrial and service sectors.[42] GDP per capita was approximately 64,000 CNY[43] as of 2009. In 2013, the city's annual average disposable income was 23,738.09 CNY, which is expected to increase by 14 percent over the next year.[42]

Wuhan has attracted foreign investment from over 80 countries, with 5,973 foreign-invested enterprises established in the city with a total capital injection of $22.45 billion USD.[42] Among these, about 50 French companies have operations in the city, representing over one third of French investment in China, and the highest level of French investment in any Chinese city.[44] The municipal government offers various preferential policies to encourage foreign investment, including tax incentives, discounted loan interest rates and government subsidies.

Wuhan is an important center for economy, trade, finance, transportation, information technology, and education in China. Its major industries include optic-electronic, automobile manufacturing, iron and steel manufacturing, new pharmaceutical sector, biology engineering, new materials industry and environmental protection. Wuhan Iron and Steel (Group) Co. and Dongfeng-Citroen Automobile Co., Ltd headquartered in the city. Environmental sustainability is highlighted in Wuhan's list of emerging industries, which include energy efficiency technology and renewable energy.[42]

Wuhan is one of the cities with the most competitive force for domestic trade in China. Wuhan, close next to Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou in its volume of retail, is among the top list of China's metropolises. Wuhan Department Store, Zhongshang Company, Hanyang Department Store, and Central Department Store enjoy highest reputation and are Wuhan's four major commercial enterprises and listed companies. Hanzhengjie Small Commodities Market has been prosperous for hundreds of years and enjoys a worldwide reputation.

There are 35 higher educational institutions including the well-known Wuhan University, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 3 state-level development zones and many enterprise incubators. Wuhan ranks third in China in overall strength of science and technology.[45]

Industrial zones

Major industrial zones in Wuhan include:

Wuhan Donghu New Technology Development Zone is a national level high-tech development zone. Optical-electronics, telecommunications, and equipment manufacturing are the core industries of Wuhan East Lake High-Tech Development Zone (ELHTZ) while software outsourcing and electronics are also encouraged. ELHTZ is China's largest production centre for optical-electronic products with key players like Changfei Fiber-optical Cables (the largest fiber-optical cable maker in China), and Fenghuo Telecommunications. Wuhan Donghu New Technology Development Zone also represents the development centre for China's laser industry with key players such as HUST Technologies and Chutian Laser being based in the zone.[46]

- Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone

Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone is a national level industrial zone incorporated in 1993.[47] Its current zone size is about 10–25 square km and it plans to expand to 25–50 square km. Industries encouraged in Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone include Auto-mobile Production/Assembly, Biotechnology/Pharmaceuticals, Chemicals Production and Processing, Food/Beverage Processing, Heavy Industry, and Telecommunications Equipment.

- Wuhan Export Processing Zone

Wuhan Export Processing Zone was established in 2000. It is located in Wuhan Economic and Technology Development Zone, planned to cover 2.7 sq km of land. The first 0.7 sq km area has been launched.[48]

- Wuhan Optical Valley (Guanggu) Software Park

Wuhan Optical Valley (Guanggu) Software Park is located in Wuhan Donghu New Technology Development Zone. Wuhan Optics Valley Software Park is jointly developed by East Lake High-Tech Development Zone and Dalian Software Park Co., Ltd.[49] The planned area is 0.67 km2 with total floor area of 600,000 square meters. The zone is 8.5 km (5.28 mi) away from the 316 National Highway and is 46.7 km (29.02 mi) away from the Wuhan Tianhe Airport.

- Wuhan Biolake

Biolake is an industry base established in 2008 in the Optics Valley of China. Located in East Lake New Technology Development Zone of Wuhan, Biolake covers 15 km2 (5.8 sq mi), and has six parks including Bio-innovation Park, Bio-pharma Park, Bio-agriculture Park, Bio-manufacturing Park, Medical Device Park and Medical Health Park, to accommodate both research activities and living.[50][51][52][53][54]

Education and scientific research

Wuhan contains three national development zones and four scientific and technological development parks, as well as numerous enterprise incubators, over 350 research institutes, 1470 hi-tech enterprises, and over 400,000 experts and technicians.

By the end of 2013, in Wuhan there were 1024 kindergartens with 224.3 thousand children, 590 primary schools with 424 thousand students, 369 general high schools with 314 thousand students, 105 secondary vocational and technical schools with 98.6 students and 80 colleges and universities with 966.4 thousand undergraduates and junior college students, and 107.4 thousand postgraduate students.[55]

Wuhan University, located near East Lake, was founded in 1893 as Ziqiang Institute by Zhang Zhidong and named a national university in 1928. In 2000 three other first-rated universities were merged with the original university, forming a new university with 36 schools in 6 faculties. From the 1950s it has received international students from more than 109 countries.[56] Among its staff, 7 are Chinese Academy of Sciences fellows, and 8 are Chinese Academy of Engineering fellows.[57] Huazhong University of Science and Technology is another Project 985 university in Wuhan. Founded in 1953 as Huazhong Institute of Technology, it combined with three other universities (including former Tongji Medical University founded in 1907) in 2000 to form the new HUST, and has 42 schools and departments covering 12 comprehensive disciplines.[58][59]

Founded in 1958, the Wuhan Branch of Chinese Academy of Sciences is one of the twelve national branches of CAS. It is composed of 9 independent organizations, including the headquarters at Xiaohongshan, Wuchang. It has had a staff of 3900, among which 8 are CAS fellows, and one is a Chinese Academy of Engineering fellow. Up to 2013, the achievements gained by WHB have won 23 National Awards and 778 Provincial Awards.[60] Wuhan Research Institute of Post and Telecommunications (now known as FiberHome Technologies Group) is the national center for optical communication research in China, where the first optical fiber in the country was produced.[61]

Wuhan University of Technology is another major national University in the area. Founded in the year 2000, Wuhan University of Technology is merged from three major universities, Wuhan University of Technology (established in 1948), Wuhan Transportation University (established in 1946) and Wuhan Automotive Polytechnic University (established in 1958). Wuhan University of Technology is one of the leading Chinese universities accredited by the Ministry of Education and one of the universities constructed in priority by the "State Project 211" for Chinese higher education institutions. The University has three main campuses located in the Wuchang District.

Media

The modern newspapers in Wuhan can be dated back to 1866, when Hankow Times, an English newspaper, was founded. Before 1949, more than 50 newspapers and magazines were published by foreigners in Wuhan. Chao-wen Hsin-pao, founded by Ai Xiaomei in 1873, was the first Chinese newspaper appeared in Hankou. During the Northern Expedition era, journalism in Wuhan was pushed to a climax. More than 120 newspapers and periodicals, including national newspapers such as Central Daily News and Republican Daily News, were founded or published there.[62] Chutian Metropolis Daily and Wuhan Evening News are two major local commercial tabloid newspapers. Both of them have entered the list of 100 most widely circulated newspapers of the world.

Culture

Wuhan is one of the birthplaces of the brilliant ancient Chu Culture in China. Han opera, which is the local opera of Wuhan area, was one of China's oldest and most popular operas. During the late Qing dynasty, Han opera, blended with Hui opera, gave birth to Peking opera, the most popular opera in modern China. Therefore, Han opera is called "mother of Peking opera" in China.

Language

Wuhan natives speak a variety of Southwestern Mandarin Chinese. Some of the local Wuhan residents speak the Wuhan dialect (Chinese: 武汉方言), and it differs slightly between regions.

Cuisine

“No need to be particular about the recipes, all food have their own uses. Rice wine and tangyuan are excellent midnight snacks, while fat bream and flowering Chinese cabbages are great delicacies.” Hankou Zhuzhici (an ancient book recording stories about Wuhan) produced during the Daoguang Period of the Qing dynasty, reflects indirectly the eating habits and a wide variety of distinctive snacks with a long history in Wuhan, such as Qingshuizong (a pyramid-shaped dumpling made of glutinous rice wrapped in bamboo or reed leaves) in the Period of the Warring States, Chunbinbian in Northern & Southern dynasties, mung bean jelly in the Sui dynasty, youguo (a deep-fried twisted dough stick) in the Song and Yuan dynasties, rice wine and mianwo in the Ming and Qing dynasties as well as three-delicacy stuffed skin of bean milk, tangbao (steamed dumpling filled with minced meat and gravy) and hot braised noodles in modern times.

Besides the snacks, Hubei cuisine ranks as one of China’s ten major styles of cooking with many representative dishes. With development of more than 2,000 years, Hubei cuisine, originating in Chu Cuisine in ancient times, has developed a lot of distinctive dishes with its own characteristics, such as steamed blunt-snout bream in clear soup, preserved ham with flowering Chinese cabbage, etc.

Guozao is a popular way to say having breakfast in Wuhan. It is generally said that Guangzhou is the paradise for eating and Shanghai for dressing, while Wuhan is a combination of both. Sitting favorably at the heart of China, Wuhan has gathered and mixed together various habits and customs from neighboring cities and provinces in all directions, which gives rise to a saying of concentrating diverse customs from different places.

- Hot and Dry Noodles, Re-gan mian (热干面) consists of long freshly boiled noodles mixed with sesame paste. The Chinese word re means hot and gan means dry. It is considered to be the most typical local food for breakfast.

- Duck's neck or Ya Bozi (鸭脖子) is a local version of this popular Chinese dish, made of duck necks and spices.

- Bean skin or Doupi (豆皮)is a popular local dish with a filling of egg, rice, beef, mushrooms and beans cooked between two large round soybean skins and cut into pieces, structurally like a stuffed pizza without enclosing edges.

- Soup dumpling or Xiaolongtangbao(小笼汤包)is a kind of dumpling with thin skin made of flour, steamed with very juicy meat inside, so that is why it is called Tang (soup) Bao (bun), because every time one takes a bite from it the soup inside spills out.

- A salty doughnut or Mianwo (面窝) is a kind of doughnut with a salty taste. It's much thinner than a common doughnut, and is a typical Wuhan local food.

Notable people

- Yu Boya (俞伯牙) – ancient Chinese musician whose musical composition "Flowing Water" was burned on a CD carried by the U.S. space probe Voyager 1 as a representative of the earth civilization in the hope of being found by extraterrestrial species.

- Wei Brian - Chinese entrepreneur

- Peng Xiuwen – composer and conductor

- Paula Tsui – singer who spent most of her singing career in Hong Kong

- Xu Fan – actress

- Liu Yifei – actress and singer

- Li Yuanhong – former President of the Republic of China.

- Xiong Bingkun (熊秉坤) – soldier who started the Wuhan Uprising in the Chinese Revolution of 1911 which gave birth to the Republic of China, Asia's first democratic country.

- Chang-Lin Tien – seventh Chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley (1990–1997), the first Asian to head a major university in the United States.

- Li Ting – female tennis player, Olympic gold medalist (in woman's doubles, Athens 2004)

- Fu Mingxia – female diver, four-time Olympic gold Medalist (1 in Barcelona 1992, 2 in Atlanta 1996, 1 in Sydney 2000), the only diver that had won gold medals at 3 Olympiads as well as one of the very few divers in the world who are able to win world championship in both platform diving and springboard diving. diver

- Zhou Jihong – woman diving athlete, Olympic gold medalist (Los Angeles 1984), the first Chinese who has won an Olympic gold medal in diving.

- Qiao Hong – woman table tennis player, two-time Olympic gold medalist (in woman's doubles, Barcelona 1992, Atlanta 1996)

- Wu Yi – former Vice-Premier and Minister Of Health of the People's Republic of China[63]

- Xiao Hailiang – Olympic gold medalist (in 3m springboard synchronized diving, Sydney 2000) diver

- Gao Ling – professional badminton player, two-time Olympic gold medalist (Sydney 2000, Athens 2004)

- Li Na – female tennis player, Champion of the French Open 2011 and Australian Open 2014

- Wang Kai – actor

- Chi Li – modern writer

- Zhou Mi – musician, member of the band Super Junior M

- Tang Jieli – AIBA Women's Boxing World Champion[64]

- Tian Yuan – singer and actress

- Samuel David Hawkins - American soldier in the Korean War who was captured by the North, subsequently defected to China at the time of the Korean Armistice Agreement. He worked as a mechanic in Wuhan before returning to the US in 1957.

Twin towns – Sister cities

-

Oita, Japan (1979.09.07)

Oita, Japan (1979.09.07) -

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA (1982.09.08)

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA (1982.09.08) -

Bordeaux, Aquitaine, France (since 1998)[65]

Bordeaux, Aquitaine, France (since 1998)[65] -

St. Louis, Missouri, USA (2004.09.27)

St. Louis, Missouri, USA (2004.09.27) -

Christchurch, New Zealand (2006.04.04)[66]

Christchurch, New Zealand (2006.04.04)[66]  Tijuana, Mexico (since 2013)[67]

Tijuana, Mexico (since 2013)[67] San Francisco, California, USA (2013.11.20)[68]

San Francisco, California, USA (2013.11.20)[68] Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia (since 2015)[69]

Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia (since 2015)[69] Markham, Ontario, Canada (2006.09.12)

Markham, Ontario, Canada (2006.09.12) Manchester, England (1996)

Manchester, England (1996) Chalcis, Greece (2015) [70]

Chalcis, Greece (2015) [70]

Diplomatic representation

There are four countries that have consulates in Wuhan:

The U.S. Consul General, the Honorable Ms. Diane L. Sovereign, was stationed in Wuhan from November 30, 2009 to 2012. The office of the U.S. Consulate General, Central China (located in Wuhan) celebrated its official opening on November 20, 2008 and is the first new American consulate in China in over 20 years.[75][76]

Japan[77] and Russia[78] will establish consular offices in Wuhan.

See also

- List of tallest buildings in Wuhan

- 1954 Yangtze River Floods

- List of cities in the People's Republic of China by population

- List of current and former capitals of subnational entities of China

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

- Phoenix Towers

Notes

- 1 2 "Wuhan Statistical Yearbook 2010" (PDF). Wuhan Statistics Bureau. Retrieved July 31, 2011.p. 15

- 1 2 "2013年武汉市国民经济和社会发展统计公报". Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ↑ "武汉市2010年国民经济和社会发展统计公报". Wuhan Statistics Bureau. May 10, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ↑ "Illuminating China's Provinces, Municipalities and Autonomous Regions". PRC Central Government Official Website. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- 1 2 "Focus on Wuhan, China". The Canadian Trade Commissioner Service. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Foreign News: On To Chicago". Time. June 13, 1938. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ Jacob, Mark (May 13, 2012). "Chicago is all over the place". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ↑ "中央机构编制委员会印发《关于副省级市若干问题的意见》的通知. 中编发[1995]5号". 豆丁网. 1995-02-19. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- 1 2 Stephen R. MacKinnon (2002). Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900-1950. University of Hawaii Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0824825188.

- ↑ "AN AMERICAN IN CHINA: 1936-39 A Memoir". Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ↑ Stephen R. MacKinnon. Wuhan, 1938: War, Refugees, and the Making of Modern China. University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0520254459.

- ↑ "China: Administrative Division of Húbĕi / 湖北省". Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ↑ "The engagement at the Red Cliffs took place in the winter of the 13th year of Jian'an, probably about the end of 208."(de Crespigny 1990:264)

- ↑ Wan: Page 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 戴逸, 龔書鐸. [2002] (2003) 中國通史. 清. Intelligence press. ISBN 962-8792-89-X. pp 86-89.

- ↑ Fenby, Jonathan. [2008] (2008). The History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power. ISBN 978-0-7139-9832-0. pg 107, pg 116, pg 119.

- 1 2 Welland, Sasah Su-ling. [2007] (2007). A Thousand Miles of Dreams: The Journeys of Two Chinese Sisters. Rowman Littlefield Publishing. ISBN 0-7425-5314-0, ISBN 978-0-7425-5314-9. pg 87.

- ↑ http://surfcity.kund.dalnet.se/sino-japanese-1938.htm

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wang, Ke-wen. [1998] (1998). Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture and Nationalism. Taylor & Francis Publishing. ISBN 0-8153-0720-9, ISBN 978-0-8153-0720-4. pp 390-391.

- 1 2 王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 #6 民國. 中華書局. ISBN 962-8885-29-4. pp 3-7.

- ↑ Spence, Jonathan D. [1990] (1990). The Search for Modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30780-8, ISBN 978-0-393-30780-1. pp 250-256.

- ↑ Harrison Henrietta. [2000] (2000). The Making of the Republican Citizen: Political Ceremonies and Symbols in China, 1911-1929. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829519-7, ISBN 978-0-19-829519-8. pp 16-17.

- ↑ Liu, Haiming. [2005] (2005). The Transnational History of a Chinese Family: Immigrant Letters, Family Business and Reverse Migration. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3597-2, ISBN 978-0-8135-3597-5.

- ↑ Bergere, Marie-Claire. Lloyd Janet. [2000] (2000). Sun Yat-sen. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4011-9, ISBN 978-0-8047-4011-1. p 207.

- ↑ 雙十節是? 陸民眾:「國民黨」國慶. Tvbs.com.tw. Retrieved on 2011-10-08.

- ↑ Zhongshan Warship

- 1 2 3 4 Fenby, Jonathan Chiang Kai-Shek China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost, New York: Carroll & Graf, 2004 page 447.

- 1 2 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年) (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ↑ Wunderground Archives (January 9, 2008). "Temperatures in Wuhan". Wunderground. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ↑ 为什么重庆、武汉、南京有“三大火炉”之称? (in Chinese). Guangzhou Popular Science News Net (广州科普资讯网). 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2014-11-12.

- ↑ http://cdc.cma.gov.cn/dataSetLogger.do?changeFlag=dataLogger

- ↑ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ "武汉市2010年第六次全国人口普查主要数据公报". Wuhan Statistics Bureau. May 10, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ↑ includes 208,106 in Wuhan Economic Development Zone (武汉经济技术开发区)

- ↑ includes 396,597 in Donghu New Technology Development Zone (东湖新技术开发区), 67,641 in Donghu Scenic Travel Zone (东湖生态旅游风景区), and 36,245 in Wuhan Chemical Industry Zone (武汉化学工业区)

- ↑ Tianxingzhou highway-railway Bridge in Wuhan opens to traffic. english.cnhubei.com 2009-12-28

- ↑ Two high-speed rail links start April 1

- ↑ [Source: Beijing (AFP, Sat December 26, 7:54 am ET]

- 1 2 "> Asia > China > Wuhan Metro". UrbanRail.Net. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ↑ "武汉建设网-国内最长轻轨今晨贯通 力争7月28日通车". Zdgc.whjs.gov.cn. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ↑ "武汉三大名胜之古琴台 One of the Three Famous Ancient Sites the Lute Platform". Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "China Regional Spotlight: Wuhan, Hubei Province", China Briefing, Shanghai, 27 August 2013.

- ↑ Almanac of Wuhan 2009, ranking 11th in mainland China: Wuhan Bureau of Statistics, Chapter 1 Section 9 http://www.whtj.gov.cn/documents/tjnj2009/1/1-9.htm

- ↑ People's Daily Online (October 25, 2005). "Wuhan absorbs most French investment in China". People's Daily. Retrieved October 23, 2006.

- ↑ 大汉网络 (September 3, 2004). "The Thoroughfare to Nine Provinces-Wuhan City". Cnhubei.com. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Invest in Wuhan-Wuhan East Lake Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone - China Industrial Space". Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Wuhan Economic & Technological Development Zone". Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Wuhan Export Processing Zone". Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Wuhan Optical Valley Software Park". Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Gwinnett Chamber Economic Development signed an MOU with the Wuhan (China) National Bio-industry Base (Biolake)". Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Profile of Biolake". Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Medicilon and Wuhan Biolake successfully organized a bio-pharmaceutical salon". Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "CLSC Partners with Wuhan Biolake for China Office". Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Biolake and the Booming Bio-industry in Central China". Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ 武汉市统计局; 国家统计局武汉调查队. "2013年武汉市国民经济和社会发展统计公报" [2013 Statistic Report of National Economy and Social Development in Wuhan]. 武汉组工网. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Wuhan University". Chinadaily. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Facts & Figures". Wuhan University. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Wuhan: Huazhong University of Science and Technology". Study Abroad in China. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ↑ "History". HUST. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Introduction". CAS Wuhan Branch. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ "FiberHome Technologies Group". China Daily. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ "武汉市志(1840-1985)·新闻志·概述" [Wuhan City Annals 1840-1985·News Media Annals·Introduction]. 武汉市地情文献. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ↑ "#2 Wu Yi Vice Premier, minister of health". Forbes. November 2005.

- ↑ "图文:女子拳击世锦赛落幕 汤洁丽夺80KG级冠军". Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Bordeaux, ouverte sur l'Europe et sur le monde". Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "Wuhan, China : Christchurch City Council". Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "Tijuana, Mexico becomes Wuhan's 20th sister city". Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ "Wuhan and San Francisco establish friendship relation". Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "KK formally establishes relations with Wuhan". Daily Express. 27 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ "Chalcis and Wuhan become sister cities". Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ French Foreign Ministry (August 2, 2012). "Consulat General de France a Wuhan".

- ↑ US Department of State (November 23, 2008). "Consulate General of the United States Wuhan, China".

- ↑ Embassy of the Republic of Korea in China (December 23, 2010). "Welcome to the Embassy of the Republic of Korea in China".

- ↑ UK Government (January 6, 2015). "Consulate General of the United Kingdom Wuhan, China".

- ↑ "U.S. Opens Consulate in China Industry Center Wuhan". Associated Press. November 20, 2008.

- ↑ US Department of State (November 20, 2008). "The United States Consulate General in Wuhan, China Opens on November 20, 2008".

- ↑ "日本计划在汉设领事办事处". Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Putin assures that Russia and China are getting closer". Retrieved September 9, 2015.

References

- Chi, Li (2000). Lao Wuhan (Old Wuhan): Yong Yuan De Lang Man... (part of the "Lao Cheng Shi" series). Nanjing: Jiangsu Meishu Chubanshe.

- Coe, John L. (1962). Huachung University (Huazhong Daxue). New York: United Board for Christian Higher Education.

- Danielson, Eric N. (2005). "The Three Wuhan Cities," pp.1–96 in The Three Gorges and the Upper Yangzi. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish/Times Editions.

- Latimer, James V. (1934). Wuhan Trips: A Book on Short Trips in and Around Hankow. Hankow: Navy YMCA.

- MacKinnon, Stephen R. (2000). "Wuhan's Search for Identity in the Republican Period," in Remaking the Chinese City, 1900–1950, ed. by Joseph W. Esherick. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Rowe, William T. (1984). Hankou: Commerce and Society, 1796–1889. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Rowe, William T. (1988). Hankou: Conflict and Community in a Chinese City, 1796–1895. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Song, Xiaodan and Zhu, Li (1999). Wuhan Jiu Ying (Old Photos of Wuhan). Beijing: Renmin Meishu Chubanshe (People's Fine Arts Publishing House).

- Walravens, Hartmut. "German Influence on the Press in China." - In: Newspapers in International Librarianship: Papers Presented by the Newspaper Section at IFLA General Conferences. Walter de Gruyter, January 1, 2003. ISBN 3110962799, 9783110962796.

- Also available at (Archive) the website of the Queens Library - This version does not include the footnotes visible in the Walter de Gruyter version

- Also available in Walravens, Hartmut and Edmund King. Newspapers in international librarianship: papers presented by the newspapers section at IFLA General Conferences. K.G. Saur, 2003. ISBN 3598218370, 9783598218378.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wuhan. |

- Wuhan Government website

- Wuhan Time

Wuhan travel guide from Wikivoyage

Wuhan travel guide from Wikivoyage

| Preceded by Guangzhou |

Capital of China 1926 |

Succeeded by Nanjing |

| Preceded by Nanjing |

(wartime) Capital of China 1937 |

Succeeded by Chongqing (wartime) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest cities or towns in China Sixth National Population Census of the People's Republic of China (2010) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Shanghai  Beijing |

1 | Shanghai | Shanghai | 20,217,700 | 11 | Foshan | Guangdong | 6,771,900 |  Chongqing  Guangzhou |

| 2 | Beijing | Beijing | 16,858,700 | 12 | Nanjing | Jiangsu | 6,238,200 | ||

| 3 | Chongqing | Chongqing | 12,389,500 | 13 | Shenyang | Liaoning | 5,890,700 | ||

| 4 | Guangzhou | Guangdong | 10,641,400 | 14 | Hangzhou | Zhejiang | 5,578,300 | ||

| 5 | Shenzhen | Guangdong | 10,358,400 | 15 | Xi'an | Shaanxi | 5,399,300 | ||

| 6 | Tianjin | Tianjin | 10,007,700 | 16 | Harbin | Heilongjiang | 5,178,000 | ||

| 7 | Wuhan | Hubei | 7,541,500 | 17 | Dalian | Liaoning | 4,222,400 | ||

| 8 | Dongguan | Guangdong | 7,271,300 | 18 | Suzhou | Jiangsu | 4,083,900 | ||

| 9 | Chengdu | Sichuan | 7,112,000 | 19 | Qingdao | Shandong | 3,990,900 | ||

| 10 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 7,055,071 | 20 | Zhengzhou | Henan | 3,677,000 | ||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||

|