Central Park jogger case

| Time | 9 pm – 10 pm |

|---|---|

| Date | April 19, 1989 (date of attacks) |

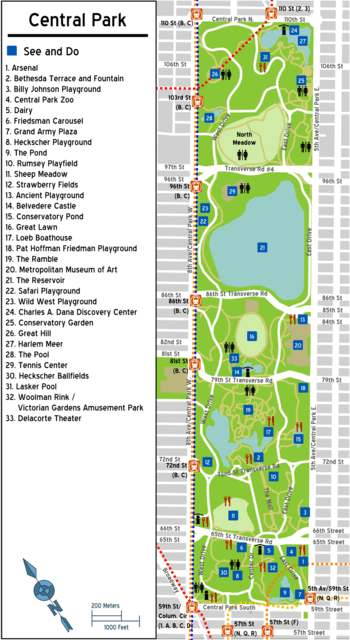

| Location | Central Park, New York City, between 105th Street and 97th Street. |

| Non-fatal injuries | Assault, rape, and sodomy of Trisha Ellen Meili, and assault of others. |

| Accused | 11 suspects were charged. |

| Convicted | 6 suspects pleaded guilty. 5 suspects were tried before juries, and convicted in 1990; the convictions of four were appealed, and upheld on appeal (but the 5 convictions were vacated in 2002; the District Attorney stopped short of saying the 5 were innocent, but withdrew all charges and did not seek a retrial). |

| Charges | Assault, robbery, riot, rape, sexual abuse, and attempted murder. |

| Verdict | The 5 suspects who went to trial received sentences ranging from 5–10 to 5–15 years, and served between 6 and 13 years in prison. |

| Litigation | The 5 who had been convicted at trial sued New York City in 2003 for malicious prosecution, racial discrimination, and emotional distress. The city settled the case for $41 million in 2014. As of December 2014, the 5 were pursuing an additional $52 million in damages from New York State. |

The Central Park jogger case concerned the assault, rape, and sodomy of Trisha Meili, a female jogger, and attacks on others in New York City's Central Park, on April 19, 1989. The attack on the female jogger left her in a coma for 12 days. Meili was a 28-year-old investment banker at the time. The attacks were, according to The New York Times, "one of the most widely publicized crimes of the 1980s."[1]

Five juvenile males—four black and one of Hispanic descent—were tried, variously, for assault, robbery, riot, rape, sexual abuse, and attempted murder. They were convicted of most charges by juries in two separate trials in 1990, and received sentences ranging from five to 15 years. Four of the convictions were appealed; they were affirmed by appellate courts. The defendants spent between six and 13 years in prison.

In 2002, Matias Reyes, a Hispanic male who had been a juvenile at the time of the attack, confessed to raping the jogger, and DNA evidence confirmed his involvement in Meili's rape. He also said he committed the rape alone. Reyes at the time of his confession was a convicted serial rapist and murderer, serving a life sentence. He was not prosecuted for raping Meili, because the statute of limitations had passed by the time Reyes confessed. District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, stopping short of saying the five were innocent, suggested to the court that their convictions related to the assault and rape of Meili and the attacks on others to which they had confessed be vacated (a legal position in which the parties are treated as though no trial has taken place), withdrew all charges, and did not seek a retrial. Their convictions were vacated in 2002.

The five who had been convicted sued New York City in 2003 for malicious prosecution, racial discrimination, and emotional distress. The city refused to settle the suits for a decade under then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg, because the city's lawyers felt they would win. However, after Bill de Blasio became mayor and supported the settlement, the city settled the case for $41 million in 2014. As of December 2014, the five men were pursuing an additional $52 million in damages from New York State in the New York Court of Claims.

Victim

The victim, then 28-year-old Trisha Ellen Meili, lived on East 83rd Street between York Avenue and East End Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. At the time of the attack she was a vice president in the corporate finance department and energy group of the Wall Street investment bank Salomon Brothers.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] At the time of the attack, she weighed less than 100 pounds (45 kg).[9]

Meili was born in Paramus, New Jersey, and raised in affluent Upper St. Clair, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh.[10] She is the daughter and youngest of three children of John, a Westinghouse senior manager, and Jean Meili, a school board member.[2][3][9][11][12] She attended Upper St. Clair High School, graduating in 1978.[3]

Meili was a Phi Beta Kappa economics major at Wellesley College, where she received a B.A. in 1982.[2][10] The Chairman of Wellesley's Economics Department said: "She was brilliant, probably one of the top four or five students of the decade."[1] In 1986, she earned an M.A. from Yale, and an M.B.A. in Finance from the Yale School of Management.[3] She worked from the summer of 1986 on through the time of the attack as an associate and then a vice president in the corporate finance department and energy group of Salomon Brothers.[2][3][4][8][13][14][15]

Meili was referred to in most media accounts of the incident at the time simply as the "Central Park Jogger". However, two local TV stations released her name in the days immediately following the attack, and two newspapers aimed at the African-American community, The City Sun and the Amsterdam News, and black-owned talk radio station WLIB continued to do so as the case progressed.[16][17][18] Attorney Alton Maddox, Jr. claimed during a WLIB show that the case was a racist hoax, and questioned whether the jogger had in fact been hurt.[19]

In April 2003, Meili confirmed her identity to the media, published a memoir entitled I Am the Central Park Jogger, and began a career as an inspirational speaker.[20][21] She also works with victims of sexual assault and brain injury in the Mount Sinai sexual assault and violence intervention program.[22] She continues to manifest some physiological after-effects of the assault, including memory loss.[3][23][24][25]

Assault

Between 9 and 10 pm on the night of April 19, 1989, approximately 30 teenage perpetrators committed several attacks, assaults, and robberies in the northernmost part of New York City's Central Park.[26][27] The attacks on Meili and on others in the park that night were, according to The New York Times, "one of the most widely publicized crimes of the 1980s."[1]

Trisha Meili, a 28-year-old investment banker, went for a run on her usual path in Central Park shortly before 9 pm.[27][28][29] While jogging in the park, she was knocked down, dragged or chased nearly 300 feet (91 m), and violently assaulted.[8] She was raped, sodomized, and beaten almost to death.[30] Investigators' best evidence suggested she was attacked between 9:10 and 9:15 pm, on the transverse through the park from East 104th Street toward West 102nd Street, between the park's East Drive and West Drive.[8][29]

She was found naked, gagged, and tied up, covered in mud and blood, about four hours later, at 1:30 am. Meili was discovered in a shallow ravine in a wooded area of the park about 300 feet (91 m) north of the 103rd Street Transverse.[8][29][30][31][32] The first policeman who saw her said: "She was beaten as badly as anybody I've ever seen beaten. She looked like she was tortured."[4]

She was comatose for 12 days.[33] She suffered from severe hypothermia, severe brain damage, Class 4 (the most severe) hemorrhagic shock, and loss of 75–80 per cent of her blood from five deep stab wounds and a gash on one of her thighs, and internal bleeding.[3][25][32][33][34] Her skull had been fractured so badly that her left eye was removed from the eye socket, which in turn was fractured in 21 places, and she suffered as well from facial fractures.[3][25][35] Doctors attributed her survival to the cold weather as well as the cold mud in which she lay in the hours before she was discovered, which reduced her internal swelling.[3]

The initial medical prognosis was that Meili would die.[3] She was given last rites.[25] The police initially listed the attack as a probable homicide.[36] At best, doctors thought that she would remain in a permanent coma due to her injuries. She came out of her coma 12 days after her attack, and spent seven weeks in Metropolitan Hospital in East Harlem. When she emerged from her coma, she was initially unable to talk, read, or walk.[25][30] A month after the attack, she had difficulty recognizing her mother, and was unable to recall what year it was.[37]

She was transferred in early June to Gaylord Hospital, a long-term acute care center in Wallingford, Connecticut, suffering from amnesia, double-vision, and dizziness, and spent six months there working on her rehabilitation.[3][22][33] She was first able to walk again in mid-July.[23] She returned to work eight months after the attack.[38] Remarkably, she largely recovered, with some lingering disabilities related to balance and loss of vision. As a result of the severe trauma, she had no memory of the attack or of any events up to an hour before the assault, nor of the six weeks following the attack.[23]

The crime was unique in the level of public outrage it provoked. New York Governor Mario Cuomo told the New York Post: "This is the ultimate shriek of alarm."[17]

Arrests, interrogations, and confessions

According to a police investigation, the main suspects were gangs of teenagers who would assault strangers as part of an activity that became known as "wilding". New York City detectives said the phrase was used by the suspects themselves to describe their actions to police.[39] This account has been disputed by some journalists, who say that it originated in a police detective's misunderstanding of the suspects' use of the phrase "doing the wild thing", lyrics from rapper Tone Lōc's hit song "Wild Thing".[40][41]

April 19 was a night when such a series of gang attacks occurred. A group of over 30 teenagers, including the suspects, who lived in East Harlem entered Central Park at an entrance in Harlem, near Central Park North, at approximately 9 pm.[8]

The teenagers attacked and beat people as they moved south, on Central Park's East Drive, and on the park's 97th Street Transverse, between 9 pm and 10 pm.[8] Between 105th and 102nd Streets they attacked several bicyclists, hurled rocks at a cab, and attacked a man who was walking whom they knocked to the ground, assaulted, robbed, and left unconscious.[8][29] A schoolteacher out for a run was severely beaten and kicked, between 9:40 and 9:50.[8] Then, at the 97th Street Transverse at the northwest end of the Central Park Reservoir running track, at about 10 pm they attacked another jogger, bludgeoning him in the back of the head with a pipe and stick.[8][42] They pummeled two men into unconsciousness, hitting them with a metal pipe, stones, and punches, and kicking them in the head.[29][35] A police officer testified that one male jogger, who said he had been jumped by four of five black youths, was bleeding so badly he "looked like he was dunked in a bucket of blood."[43]

Responding police scooters and unmarked cars, dispatched at 9:30 pm, apprehended Raymond Santana and Kevin Richardson along with other teenagers at approximately 10:15 on Central Park West and 102nd Street.[8][29][42] Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, and Korey Wise were brought in for questioning later, after having been identified by other youths as participants in or present at some of the attacks.[29][42]

Contrary to normal police procedure, which stipulates that the names of suspects under the age of sixteen are to be withheld, the names of the arrested juveniles were released to the press before any of them had been formally arraigned or indicted, including one 14-year-old who was ultimately not charged.[17] The media's decision to print the names, photos, and addresses of the juvenile suspects while withholding Meili's identity was cited by the editors of the City Sun and the Amsterdam News to explain their own continued use of Meili's name in their coverage of the story.[44]

The five juveniles were interviewed for hours. With a parent or guardian of theirs present, Santana, McCray, and Richardson all made video statements.[45] Wise made a number of statements, on his own, in accordance with the law.[45] Salaam told the police he was 16 years old and showed them identification to prove it, which permitted the police to question him without a parent.[45] After Salaam's mother arrived the police stopped the questioning, but Salaam's admissions were admitted into testimony.[45] In addition, before the raped jogger was even found, one of the other boys the police had rounded up, sitting in the back of a police car, blurted that he "didn't do the murder," but that he knew who did ... Antron McCray, and Kevin Richardson who was sitting beside him agreed, saying "Antron did it".[45] Later, after Raymond Santana was interrogated about the rape and while he was being driven to another precinct, he on his own exclaimed: "I had nothing to do with the rape. All I did was feel her tits."[45]

All five confessed to a number of the attacks committed in the park that night, and implicated one or more of the others.[29][45] None of the five said they themselves actually raped the jogger, but each confessed to being an accomplice to the rape.[29] All five said that they themselves had only helped restrain the jogger, or touched her, while one or more others raped her.[45] Antron McCray said that a "Puerto Rican kid with a hoodie" had been the one who raped the jogger.[29] While he was incarcerated in the Rikers Island jail, Korey Wise told the older sister of a friend of his, according to her testimony, that he'd only held the jogger down.[45]

Yusef Salaam made verbal admissions, but refused to sign a confession or make one on videotape. Salaam was, however, implicated by all of the other four, and convicted.

Six others were charged with committing crimes in the park that night as well. They pleaded guilty, and received sentences of six months to four and a half years.[29]

Salaam's supporters and attorneys charged on appeal that he had been held by police without access to parents or guardians, but as the majority appellate court decision noted, that was because Salaam had initially lied to police in claiming to be 16, and had backed up his claim with a transit pass that indeed (falsely, as it turned out) indicated that he was 16. If a suspect has reached 16 years of age, his parents or guardians no longer have a right to accompany him during police questioning, or to refuse to permit him to answer any questions. When Salaam informed police of his true age, police permitted his mother to be present.[46]

Although the suspects (except Salaam) had confessed on videotape in the presence of a parent or guardian, they retracted their statements within weeks, claiming that they had been intimidated, lied to, and coerced into making false confessions.[47] The detectives had indeed used ruses to convince the suspects to confess, with Salaam confessing to having been present only after he was told that fingerprints were found on the victim's clothing.[48] While the confessions themselves were videotaped, the hours of interrogation that preceded the confessions were not.

Analysis indicated that the DNA collected at the crime scene did not match any of the suspects—and that it had come from a single, as yet unknown person.[47] Since no DNA evidence tied the suspects to the crime, the prosecution's case rested almost entirely on the confessions.[17]

One of the suspects' supporters, Reverend Calvin O. Butts of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, told The New York Times, "The first thing you do in the United States of America when a white woman is raped is round up a bunch of black youths, and I think that's what happened here."[17]

Trials, convictions, sentences, and vacations of sentences

Trials and sentences

In a first trial in August 1990, defendants Yusef Salaam, Antron McCray, and Raymond Santana were acquitted of attempted murder, but convicted of rape, assault, robbery, and riot in the attacks on the jogger and others in Central Park that night.[29] Salaam and McCray were 15 years old, and Santana 14 years old, at the time of the crime,[41] and they received the maximum sentence allowed for juveniles, 5–10 years in a youth correctional facility.[26][49][50] The jury, consisting of four whites, four blacks, four Hispanics, and an Asian, deliberated for ten days before rendering its verdict.[51]

The second trial ended in December 1990.[29] Kevin Richardson, 14 years old at the time of the crime, was convicted of attempted murder, rape, assault, and robbery in the attacks on the joggers and others in the park, and sentenced to 5–10 years. Korey Wise, 16 years old at the time of the crime, was acquitted of those charges, but convicted of sexual abuse, assault, and riot in the attack on the jogger and others in the park, and sentenced to 5–15 years.[29] After the verdict, Wise shouted at the prosecutor: "You’re going to pay for this. Jesus is going to get you. You made this up."[52]

The jogger, who took the stand, said: "I'll tell you what—I didn't feel wonderful about the boys' defense attorneys, especially the one who cross-examined me. He was right in front of my face and, in essence, calling me a slut by asking questions like 'When's the last time you had sex with your boyfriend?'"[23] Wise's lawyer had also asked her whether she had been assaulted by men in her life, suggested that a man she knew may have attacked her, and implied her injuries were not as severe as they had been made out to be.[53]

Jurors interviewed after the trial said that they were not convinced by the confessions, but were impressed by the physical evidence introduced by the prosecutors: semen, grass, dirt, and two hairs "consistent with" the victim's hair[26]:6 recovered from Richardson's underpants.[54] Richardson received a sentence of 5–10 years, and Wise, who had been tried as an adult, a sentence of 5–15 years. Four of the convictions were affirmed on appeal, while Santana did not appeal.[26][29]

The five defendants spent between six and thirteen years in prison.[55] After they got out of prison, Santana sold drugs and was sent back to prison, Wise was re-arrested on another matter, and McCray moved away.[56]

The case attracted nationwide attention and was the subject of many articles and books, both during the trials and after the convictions.[57]

Convictions vacated

In 2001, convicted serial rapist and murderer Matias Reyes, a Puerto-Rican-born male serving a life sentence for other crimes, but not, at that point, associated by the police with the attack on Meili, met Wise in an upstate New York prison, the Auburn Correctional Facility.[45][58] Subsequently, Reyes declared in 2002 that he had assaulted and raped the jogger that night, when he was 17. He said that he had acted alone.[59][60] At the time of the attack, he was working at an East Harlem bodega on Third Avenue and 102nd Street, and living in a van on the street.[60][61] He provided a detailed account of the attack, details of which were corroborated by other evidence.[26] The DNA evidence confirmed his participation in the rape, identifying him as the sole contributor of the semen found in and on the victim "to a factor of one in 6,000,000,000 people".[26] DNA analysis of the strands of hair found in Richardson's underpants established that the hair did not belong to the victim.[62] The victim had been tied up with her T-shirt in a distinctive fashion that Reyes used again on later victims.[26] Reyes was not prosecuted because the statute of limitations had passed, and thus his admissions did not place him at further risk.[45][63] Reyes had been convicted of raping four other women and killing one of them, and a defense psychiatrist in his trial had concluded that Reyes was not capable of telling the truth.[45] Some investigators in the district attorney's office nevertheless theorized that Reyes and the five convicted youths were all involved in the attack on the jogger.[64]

Reyes's confession, plus DNA evidence confirming his participation in the rape, led the district attorney's office to recommend vacating the convictions of the defendants originally found guilty and sentenced to prison. Supporters of the five defendants again claimed their confessions had been coerced. An examination of the inconsistencies between their confessions led the prosecutor to question the veracity of their confessions. District Attorney Robert M. Morgenthau's office wrote:

A comparison of the statements reveals troubling discrepancies. ... The accounts given by the five defendants differed from one another on the specific details of virtually every major aspect of the crime—who initiated the attack, who knocked the victim down, who undressed her, who struck her, who held her, who raped her, what weapons were used in the course of the assault, and when in the sequence of events the attack took place. ... In many other respects the defendants' statements were not corroborated by, consistent with, or explanatory of objective, independent evidence. And some of what they said was simply contrary to established fact.[26]

District Attorney Morgenthau stopped short of saying the five were innocent, but he withdrew all charges and did not seek a retrial.[65] Based on Reyes' confession, the DNA evidence, and the unreliable nature of the confessions, Morgenthau recommended that the convictions be vacated. In light of the "extraordinary circumstances" of the case, the prosecutor recommended that the court vacate not only the convictions related to the assault and rape of Meili, but also the convictions for the other crimes that night to which the defendants had confessed. His rationale was that the defendants' confessions to the other crimes were made at the same time and in the same statements as those related to the attack on Meili. Had the newly discovered evidence been available at the original trials, it might have made the juries question whether any part of the defendants' confessions were trustworthy.[26] Morgenthau's recommendation to vacate the convictions was strongly opposed by Linda Fairstein, who had overseen the original prosecution but had since left the District Attorney's Office.[47] The five defendants' convictions were vacated by New York Supreme Court Justice Charles J. Tejada on December 19, 2002. As Morgenthau recommended, Tejada's order vacated the convictions for all the crimes of which the defendants had been convicted.[66]

Despite the analysis conducted by the District Attorney's Office, New York City detectives maintained that the defendants had "most likely" been Reyes' accomplices in the assault and rape of Meili.[67] The two doctors who treated her after she was attacked stated that some of her injuries were not consistent with Reyes' claim that he acted alone.[65][68] (Their statements were contradicted at the 1990 trial by a forensic pathologist and by the New York City chief medical examiner in 2002, both of whom concluded it was impossible to tell from the victim's injuries how many people had participated in the assault).[69] Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly complained that Morgenthau's staff had denied his detectives access to "important evidence" needed to conduct a thorough investigation.[66] This claim notwithstanding, no indictments, convictions or disciplinary actions were ever taken against District Attorney's office staff members.

All of the defendants had completed their prison sentences at the time of Tejada's order, which only had the effect of clearing their names. However one defendant, Santana, remained in jail, convicted of a later, unrelated crime, though his attorney said that his sentence in that case had been extended because of his conviction in the Meili attack. All five were removed from New York State's sex offender registry.[66][70][71]

Armstrong Report

New York City Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly commissioned a panel of three lawyers in 2002 to review the case.[72] The panel was made up of two prominent lawyers, Michael F. Armstrong, the former chief counsel to the Knapp Commission which had investigated New York City police corruption in the 1970s, and Jules Martin, a New York University Vice President, as well as Stephen Hammerman, deputy police commissioner for legal affairs.[45][72][73][74][75] The panel issued a 43-page report in January 2003.[72]

The panel disputed Reyes's claim that he alone had raped the jogger.[45][72][73] The panel said his confession may have been motivated by prison threats (Wise was a member of the Bloods gang), or by a desire to transfer to a more desirable prison; after he confessed, he was re-admitted to a small, more desirable prison from which he had been thrown out.[45][72][73] It insisted there was "nothing but his uncorroborated word" that he acted alone.[72] Armstrong said the panel believed: "the word of a serial rapist killer is not something to be heavily relied upon."[72]

The report concluded that the five men whose convictions had been vacated had "most likely" participated in the beating and rape of the jogger and that that the "most likely scenario" was that "both the defendants and Reyes assaulted her, perhaps successively."[45][72] The report said it was most likely that the defendants attacked the jogger, and Reyes, drawn by her screams, "either joined in the attack as it was ending or waited until the defendants had moved on to their next victims before descending upon her himself, raping her and inflicting upon her the brutal injuries that almost caused her death."[45][72]

The report insisted that the confessions of the five defendants had not been coerced.[72][73] It noted that some of the defendants repeated their confessions in parole hearings subsequent to their convictions.[72] The report said as to inconsistencies in the defendants' statements that they were "fully explored" in pretrial hearings, and

"We believe the inconsistencies contained in the various statements were not such as to destroy their reliability. On the other hand, there was a general consistency that ran through the defendants' descriptions of the attack on the female jogger: she was knocked down on the road, dragged into the woods, hit and molested by several defendants, sexually abused by some while others held her arms and legs, and left semiconscious in a state of undress."[72][73]

"It seems impossible to say that they weren't there at all, because they knew too much," Armstrong said in an interview.[76]

Lawsuits against city and state by men whose convictions were vacated

In 2003, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana Jr., and Antron McCray sued the city for $250 million for malicious prosecution, racial discrimination, and emotional distress.[77] The city refused for a decade to settle the suits, saying that "the confessions that withstood intense scrutiny, in full and fair pretrial hearings and at two lengthy public trials" established probable cause.[78] New York City lawyers under then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg felt they would win the case.[55]

While running for mayor of New York City in 2013, Bill de Blasio pledged to settle the case if he were to win.[79] Filmmaker Ken Burns said in a November 2013 interview that Mayor–elect de Blasio had agreed to settle the lawsuit.[80]

A settlement in the case for $41 million, supported by Mayor De Blasio, was approved by a federal judge on September 5, 2014.[81] Santana, Salaam, McCray, and Richardson will each receive $7.1 million from the city for their years in prison, while Wise will receive $12.2 million. The city did not admit to any wrongdoing in the settlement.[82] The settlement averaged roughly $1 million for each year of imprisonment for the men.[83]

As of December 2014, the five men were pursuing an additional $52 million in damages from New York State in the New York Court of Claims, before Judge Alan Marin.[55] Speaking of the second suit, against the state, Santana said: "When you have a person who has been exonerated of a crime, the city provides no services to transition him back to society. The only thing left is something like this — so you can receive some type of money so you can survive."[55]

Documentary film

The daughter of documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and her husband David McMahon premiered The Central Park Five, a documentary film about the case, at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2012.[56][84] It was inspired by Sarah Burns' undergraduate thesis on racism in media coverage of the event.[85] Sarah Burns had worked for a summer as a paralegal in the office of one of the lawyers handling a lawsuit on behalf of those convicted of assaulting and raping the jogger.[56]

Ken Burns, who has compared the case to that of the Scottsboro Boys,[86] said he hoped the film would push the city to settle the case against it.[58]

On September 12, 2012, attorneys for New York City subpoenaed the production company for access to the original footage in connection with its defense of the federal lawsuit brought by some of the convicted youths against the city.[87] Celeste Koeleveld, the city's executive assistant corporation counsel for public safety, justified the subpoena on the grounds that the film had "crossed the line from journalism to advocacy" for the wrongly convicted men.[87] In February 2013, U.S. Judge Ronald L. Ellis quashed the city's subpoena.[88]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- 1 2 3 M. A. Farber (July 17, 1990). "'Smart, Driven' Woman Overcomes Reluctance". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 "Jogger Reluctantly Surrenders Privacy in Court". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 17, 1990.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Mackenzie Carpenter (March 29, 2003). "Central Park jogger writes book about her life since attack; 'How the hell did I survive?'", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

- 1 2 3 "CNN Larry King Weekend; Encore Presentation: Interview With Trisha Meili". CNN. May 3, 2003.

- ↑ "Central Park jogger tells her story in Greenfield". SentinelSource.com.

- ↑ "Trisha Meili: About Trisha". centralparkjogger.org.

- ↑ "I am the Central Park Jogger". MSNBC.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jim Dwyer and Kevin Flynn, "New Light on Jogger's Rape Calls Evidence Into Question", The New York Times

- 1 2 Linda Lee (April 27, 2003). "A Night Out With/Trisha Meili – Something to Celebrate". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Mark Kriegel (April 1, 2013). "Lived a dream life". New York Daily News.

- ↑ Mackenzie Carpenter (March 29, 2003). "Central Park jogger writes book about her life since attack". Post-Gazette. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ↑ Mackenzie Carpenter (May 13, 2003). "Central Park Jogger's recovery illustrates brain's amazing capabilities". Post-Gazette. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Central Park jogger tells her story in Greenfield". SentinelSource.com.

- ↑ "Trisha Meili: About Trisha". centralparkjogger.org.

- ↑ "‘I am the Central Park Jogger’". MSNBC.

- ↑ "Women Under Assault", Newsweek

- 1 2 3 4 5 Didion, Joan (January 17, 1991). "Sentimental Journeys". New York Review of Books. Retrieved June 21, 2007. This essay has also been published in Didion's non-fiction collection After Henry (1992).

- ↑

- ↑ Hate Crimes: Criminal Law & Identity Politics. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Trisha Meili". centralparkjogger.com.

- ↑ Meili, Trisha (2003). I am the Central Park Jogger. Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-4437-0.

- 1 2 Tara Parker-Pope (April 20, 2009). "Central Park Jogger Still Running 20 Years Later". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 "Oprah Interviews the Central Park Jogger". Oprah.com.

- ↑ "A Night Out With/Trisha Meili – Something to Celebrate". The New York Times. April 27, 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "There's a recipe for resilience". USA Today.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Affirmation in Response to Motion to Vacate Judgment of Conviction: The People of the State of New York -against- Kharey Wise, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, and Raymond Santana, Defendants" (PDF). Robert M. Morgenthau, District Attorney, New York County. December 5, 2002. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- 1 2 "Youths Rape and Beat Central Park Jogger". The New York Times. April 21, 1989.

- ↑ "LCCC grads hear healing story from Central Park jogger". Times Leader.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- 1 2 3 Stephen Robinson (April 27, 2003). "She was so badly beaten, the priest administered last rites". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ "Central Park Revisited". New York.

- 1 2 Ben Sherwood. The Survivors Club.

- 1 2 3 "Victim in 'Central Park Jogger' case brings her lessons to high school". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ "Raped N.y. Jogger Still in Coma Woman Was Stabbed 5 Times in Head Fighting Teen Attackers". Philadelphia Daily News.

- 1 2 Adam J. Jackson. The Flipside.

- ↑ "-". The Tuscaloosa News.

- ↑ "Risen from Near Death, the Central Park Jogger Makes Her Day in Court One to Remember". People.

- ↑ "Central Park Jogger recalls nothing of attack, but is now 'happy and okay'", Daily News (New York)

- ↑ Pitt, David E. (April 22, 1989). "Jogger's Attackers Terrorized at Least 9 in 2 Hours". The New York Times.

The youths who raped and savagely beat a young investment banker as she jogged in Central Park Wednesday night were part of a loosely organized gang of 32 schoolboys whose random, motiveless assaults terrorized at least eight other people over nearly two hours, senior police investigators said yesterday. Chief of Detectives Robert Colangelo, who said the attacks appeared unrelated to money, race, drugs or alcohol, said that some of the 20 youths brought in for questioning had told investigators that the crime spree was the product of a pastime called wilding.

- ↑ Cooper, Barry Michael (May 9, 1989) "The Central Park Rape" in The Village Voice.

- 1 2 Goldblatt, Mark (December 16, 2002). "Certainties and Unlikelihoods: The Central Park Jogger, 2002". National Review. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

On the night of April 19, 1989, just after 9 o'clock, it is certain, absolutely certain, that Kevin Richardson, 14, Raymond Santana, 14, Yusef Salaam, 15, Antron McCray, 15, and Kharey Wise, 16, ran amok for a half-hour across a quarter-mile stretch of Central Park—chasing after bicyclists, assaulting pedestrians, and (in two separate incidents) pummeling two men into unconsciousness with a metal pipe, stones, punches, and kicks to the head. The teens later confessed on videotape to these attacks—which they couldn't have known about unless they had participated. As recently as this year, Richardson and Santana again acknowledged their roles in these crimes.

- 1 2 3 "Central Park Revisited". New York.

- ↑ "Three Men Assaulted on Evening of 'Wilding'". Beaver County Times. October 12, 1989.

- ↑ Smith, Valerie (1998). Not Just Race, Not Just Gender: Black Feminist Readings. Routledge. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-415-90325-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Edward Conlon (October 19, 2014). "The Myth of the Central Park Five". The Daily Beast.

- ↑ "Detective Cites Coercion of Teen". Associated Press in Albany Times Union. July 24, 1990. p. B6.

Justice Thomas B. Galligan allowed the statements as evidence because Salaam gave police a student transit pass with a false birth date written in. The false birth date indicated Salaam was a year older that he was.

- 1 2 3 Schanberg, Sydney (November 26, 2002). "A Journey Through the Tangled Case of the Central Park Jogger". The Village Voice. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

Every now and again, we get a look, usually no more than a glimpse, at how the justice system really works. What we see before the sanitizing curtain is drawn abruptly down is a process full of human fallibility and error, sometimes noble, more often unfair, rarely evil but frequently unequal, and through it all inevitably influenced by issues of race and class and economic status. In short, it's a lot like other big, unwieldy institutions. Such a moment of clear sight emerges from the mess we know as the case of the Central Park jogger.

- ↑ Chris Smith (October 21, 2002). "Central Park Revisited". New York. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ↑ "The Case of the Central Park Jogger". The New York Times. August 19, 1990.

- ↑ "Shouts of 'Lie' Stun 2d Trial in Jogger Rape". The New York Times. October 23, 1990.

- ↑ The Central Park Jogger Case. ISBN 1625397429.

- ↑ "2 guilty in jog case". Daily News (New York). December 12, 1990.

- ↑ "Lawyer for Defense Questions Central Park Jogger". Eugene Register-Guard.

- ↑ "Jogger Trial Jury Relied on Physical Evidence, Not Tapes". The New York Times. December 13, 1990.

- 1 2 3 4 "Central Park Five seek an additional $52 million after reaching $41 million settlement for wrongful imprisonment in 1989 rape of jogger", Daily News (New York)

- 1 2 3 "NYC is pressed to settle Central Park jogger case". USA Today. April 6, 2013.

- ↑ Sullivan, Timothy, Unequal Verdicts: The Central Park Jogger Trials (1992, Simon & Schuster)(ISBN 067174237X).

- 1 2 "–". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Central Park jogger case settled for $40 million". nhregister.com.

- 1 2 Annaliese Griffin (April 5, 2013). "A Profile of Matias Reyes". Daily News. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ↑ Sarah Burns. The Central Park Five; The Untold Story Behind One of New York City's Most Infamous Crimes.

- ↑ "A Crime Revisited: The Decision; 13 Years Later, Official Reversal in Jogger Attack". The New York Times. December 6, 2002.

- ↑ Michael Howard Saul And Sean Gardiner (June 20, 2014). "'Central Park Five' Agree to $40 Million Wrongful-Conviction Settlement". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "Never raped jogger, ex-con insists". Daily News. New York.

- 1 2 "New York Reaches $40M Settlement in Central Park Jogger Case". NBC News.

- 1 2 3 Saulny, Susan (December 20, 2002). "Convictions and Charges Voided In '89 Central Park Jogger Attack". The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

Thirteen years after an investment banker jogging in Central Park was savagely beaten, raped and left for dead, a Manhattan judge threw out the convictions yesterday of the five young men who had confessed to attacking the woman on a night of violence that stunned the city and the nation. In one final, extraordinary ruling that took about five minutes, Justice Charles J. Tejada of State Supreme Court in Manhattan granted recent motions made by defense lawyers and Robert M. Morgenthau, the Manhattan District Attorney, to vacate all convictions against the young men in connection with the jogger attack and a spree of robberies and assaults in the park that night.

- ↑ McFadden, Robert D. (January 28, 2003). "Boys' Guilt Likely in Rape of Jogger, Police Panel Says". The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

A panel commissioned by the New York City Police Department concluded yesterday that there was no misconduct in the 1989 investigation of the Central Park jogger case, and said that five Harlem men whose convictions were thrown out by a judge last month had most likely participated in the beating and rape of the jogger. The panel also disputed the claim of Matias Reyes, a convicted killer and serial rapist, that he alone had raped the jogger. It was his confession last year that led to a sweeping re-examination of the infamous case by prosecutors, and to a reversal of all the original convictions against the five defendants.

- ↑ Hays, Elizabeth (October 28, 2002). "Protesters Want Trump's Help in Jogger Case". Daily News (New York).

- ↑ Dwyer, Jim (June 24, 2014). "Suit in Jogger Case May Be Settled, but Questions Aren't". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ↑ Innocence Project: Salaam, Richardson, McCray, Santana, Wise

- ↑ ":". Northwestern University Law School.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

- 1 2 3 4 5 Phil Hirschkorn (January 28, 2003). "Police panel slams decision to absolve men in Central Park jogger case". CNN.

- ↑ Jeffrey Ian Ross (2013). Encyclopedia of Street Crime in America. SAGE Publications.

- ↑

- ↑ Joseph Ax (December 6, 2012). "Two decades later, Central Park Jogger rape case lives on". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ The Central Park 5 Want to Settle Lawsuit October 14, 2009

- ↑ Eligon, John (April 19, 2011). "New York Won't Settle Suits in Central Park Jogger Case". The New York Times.

- ↑ Ray Sanchez and Allie Malloy (June 26, 2014). "New York City comptroller approves $40 million settlement for Central Park Five". CNN.

- ↑ Barry, Andrew (November 12, 2013). "Central Park Five Lawsuit: New York City Mayor-Elect Bill De Blasio Agrees To Settle Decade-Long Case Over Wrongful Convictions". International Business Times.

- ↑ "43 Ways Mayor de Blasio Changed New York". New York. December 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Judge Officially OKs Central Park Five's $41 Million Settlement". Gothamist.

- ↑ "New York close to settling Central Park jogger case, reportedly for $40 million". Los Angeles Times. June 20, 2014.

- ↑ Central Park jogger case at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Filmmakers Sarah Burns and David McMahon tell why they made the documentary The Central Park Five.". Daily News. New York.

- ↑ Jensen, Elizabeth (September 10, 2009). "Ken Burns, the Voice of the Wilderness". The New York Times. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- 1 2 Buettner, Russ (October 2, 2012). "City Subpoenas Film Outtakes as It Defends Suit by Men Cleared in '89 Rape". The New York Times. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ↑ Eriq Gardner. "Ken Burns Wins Fight Against New York City Over 'Central Park Five' Research". The Hollywood Reporter.

References

- Gray, Madison (January 8, 2013). "Q&A: The Wrongly Convicted Central Park Five on Their Documentary, Delayed Justice and Why They're Not Bitter". Time.

- Sarah Burns (2011). The Central Park Five: A Chronicle of a City Wilding. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-307-26614-1.

- Connor, Tracy (October 20, 2002) "48 hours: Twisting trail to teens' confessions". Daily News (New York)

- Michael F. Armstrong, et al. (January 27, 2003) "NYPD Review of the Central Park Jogger Case"

- Ryan, Nancy E. (December 5, 2002) "Affirmation in Response to Motion to Vacate Judgement of Conviction". Prosecution's detailed summary of the case.

- Timothy Sullivan (1992). Unequal Verdicts: The Central Park Jogger Trials. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-74237-X.

- McKenna, Thomas (1996). Manhattan North Homicide: Detective First Grade. St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-14010-X.

- O'Shaughnessy, Patrice (April 12, 2009). "Central Park Jogger case forever changed innocent victims & the city". Daily News (New York). Retrieved April 12, 2009. 20-year perspective on this subject

External links

- 11 Years is Too Long to Wait for Resolution

- Central Park Five – NY Daily News

- The Central Park five, again

- In re McRay, Richardson, Santana, Wise and Salaam Litigation