Wood finishing

Wood finishing refers to the process of refining or protecting a wooden surface, especially in the production of furniture where typically it represents between 5 and 30% of manufacturing costs.[1][2]

Finishing is the final step of the manufacturing process that gives wood surfaces desirable characteristics, including enhanced appearance and increased resistance to moisture and other environmental agents. Finishing can also make wood easier to clean[3] and influence other wood properties, for example tonal qualities of musical instruments and hardness of flooring.[4][5] In addition, finishing provides a way of giving low-value woods the appearance of ones that are expensive and difficult to obtain.

Planning the finish (thinking ahead)[6]

Finishing of wood requires careful planning to ensure that the finished piece looks attractive, performs well in service and meets safety and environmental requirements.[6] Planning for finishing begins with the design of furniture.[6] Care should be taken to ensure that edges of furniture are rounded so they can be adequately coated and are able to resist wear and cracking. Careful attention should also be given to the design and strength of wooden joints to ensure they do not open-up in service and crack the overlying finish.[7] Care should also be taken to eliminate recesses in furniture, which are difficult to finish with some systems, especially UV-cured finishes.[8]

Planning for wood finishing also involves thinking about the properties of the wood that you are going to finish, as these can greatly affect the appearance and performance of finishes, and also the type of finishing system that will give the wood the characteristics you are seeking.[6] For example, woods that show great variation in colour between sapwood and heartwood or within heartwood may require a preliminary staining step to reduce colour variation.[9] Alternatively, the wood can be bleached to remove the natural colour of the wood and then stained to the desired colour.[10][11] Wood’s that are coarse textured such oaks and other ring-porous hardwoods may need to be filled before they are finished to ensure the coating can bridge the pores and resist cracking. The pores in ring porous woods preferentially absorb pigmented stain and advantage can be taken of this to highlight the wood’s grain.[7] Some tropical woods such as rosewood (Dalbergia nigra), cocobolo (Dalbergia retusa) and African padauk (Pterocarpus soyauxii) contain extractives such as quinones or stilbenes retard the curing of unsaturated polyester and UV-cured acrylate coatings and other finishing systems should be used with these species.[12][13][14]

Planning for wood finishing also involves thinking the production process influences finishing. Careful handling of the wood is needed to avoid dents, scratches and soiling with dirt.[6] Wood should be marked for cutting using pencil rather than ink, however, avoid hard or soft pencil; HB is recommend for face work; 2H for joint work.[6] Care should be taken to avoid squeeze-out of glue from joints because the glue will reduce absorption of stain and finish. Any excess glue should be carefully removed to avoid further damage to the wood. Wood’s moisture content affects staining of wood.[15] Changes in wood moisture content can result in swelling and shrinkage of wood which can stress and crack coatings. Both problems can be avoided by stored wood indoors in an environment where it can equilibrate to a recommended moisture content (6 to 8%) that is similar to that of the intended end use of the furniture.[7]

Finally, consideration needs to be given to whether the finished wood will come into content with food, in which case a food safe finish should be used,[16] local environmental regulations governing the use of finishes,[17] and recycling of finished wood at the end of its life.[18]

Sanding

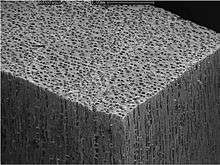

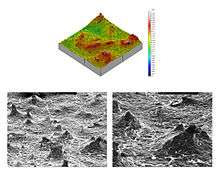

Sanding is carried out before finishing to remove defects from the wood surface that will affect the appearance and performance of finishes that are subsequently applied to the wood.[7] These defects include cutter marks and burns, scratches and indentations, small glue spots and raised grain.[7] Sanding should not be used to eliminate larger defects such as gouges, and various forms of discolouration.[7] Other techniques are used to remove these defects (see below).

The key to preparing a defect free surface is to develop a sanding schedule that will quickly eliminate defects and leave the surface smooth enough so that tiny scratches produced by sanding cannot be seen when the wood is finished.[19] A sanding schedule usually begins with sandpaper that is coarse enough to remove larger defects (typically 80 or 100 grit, but sometimes higher if the surface is already quite smooth), and progresses through a series of sandpaper grades that gradually remove the sanding scratches created by the previous sanding steps.[19] A typical sanding schedule prior to wood finishing might involve sanding wood along the grain with the following grades of sandpaper, 80, 100, 120, 150 and finishing with 180 and sometimes 220 grit.[7] The precise sanding schedule is a matter of trial and error because the appearance of a sanded surface depends on the wood you are sanding and the finish that will subsequently be applied to the wood.[19] According to Nagyszalanczy,[19] coarse grained woods with large pores such as oak hide sanding scratches better than fine grained wood and hence with such species it may be possible to use 180 or even 150 grit sandpaper as the final step in the sanding schedule.[19] Conversely, sanding scratches are more easily seen in finer grained, harder woods and also end-grain, and hence, they require finer sandpaper (220 grit) during the final sanding stage.[19] The sandpaper selected for the final sanding stage affects the colour of stained wood, and therefore when staining is part of finishing avoid sanding the wood to a very smooth finish.[7] On the other hand, according to Nagyszalanczy if you are using an oil-based finish, it is desirable to sand the wood using higher grit sandpaper (400 grit) because oil tends to highlight sanding scratches.[19]

Sanding is very good at removing defects at wood surfaces, but it creates a surface that contains minute scratches in the form of microscopic valleys and ridges, and also slivers of wood cell wall material that are attached to the underlying wood.[20][21][22] These sanding ridges and slivers of wood swell and spring-up, respectively, when sanded wood is finished with water-based finishes, creating a rough fuzzy surface. This defect is known as grain raising. It can be eliminated by wetting the surface with water, leaving the wood to dry and then lightly sanding the wood to remove the ‘raised grain’.[19]

Removing Larger Defects

Larger defects that interfere with wood finishing include dent, gouges, splits and glue spots and smears.[7] These defects should also be removed before finishing, otherwise they will affect the quality of the finished furniture or object. However, it is difficult to completely eliminate large defects from wood surfaces.

Removing dents from wood surfaces is quite straightforward as pointed out by.[7] Add a few droplets of demineralized water to the dent and let it soak in. Then put a clean cloth over the dent and place the tip of a hot iron on the cloth that lies immediately above the dent, taking great care not to burn the wood. The transfer of heat from the iron to the wood will cause compressed fibres in the dent to recover their original dimensions. As a result the dent will diminish in size or even disappear completely, although removal of large dents may require a number of wetting and heating cycles. The wood in the recovered dent should then be dried and sanded smooth to match the surrounding wood.

Gouges and holes in wood are more difficult to repair than dents because wood fibres have been cut, torn and removed from the wood. Larger gouges and splits are best repaired by patching the void with a piece of wood that matches the colour and grain orientation of the wood under repair.[7] Patching wood requires skill, but when done properly it is possible to create a repair that is very difficult to see. An alternative to patching is filling (sometimes known as stopping).[7][23] Numerous coloured fillers (putties and waxes) are produced commercially and are coloured to match different wood species. Successful filling of voids in wood requires the filler to precisely match the colour and grain pattern of the wood around the void, which is difficult to achieve in practice. Furthermore, filled voids do not behave like wood during subsequent finishing steps, and they age differently to wood. Hence, repairs to wood using fillers may noticeable.[7] Therefore filling is best used with opaque finishes rather than semitransparent finishes, which allow the grain of the wood to be seen.

Glue smears and droplets are sometimes present around the joints of furniture. They can be removed using a combination of scraping, scrubbing and sanding.[7] These approaches remove surface glue, but not the glue beneath the wood surface. Sub-surface glue will reduce the absorption of stain by wood, and may alter the scratch pattern created by sanding. Both these affects will influence the way in which the wood colors when stains are used to finish the wood. To overcome this problem it may be necessary to locally stain and touch-up areas previously covered by glue to ensure that the finish on such areas matches that of the surrounding wood.[7]

.jpg)

Basic wood finishing procedure

Wood finishing starts with sanding either by hand, typically using a sanding block or power sander, scraping, or planing. Imperfections or nail holes on the surface may be filled using wood putty or pores may be filled using wood filler. Often, the wood's color is changed by staining, bleaching, or any of a number of other techniques.

Once the wood surface is prepared and stained, the finish is applied. It usually consists of several coats of wax, shellac, drying oil, lacquer, varnish, or paint, and each coat is typically followed by sanding.

.jpg)

Finally, the surface may be polished or buffed using steel wool, pumice, rotten stone or other materials, depending on the shine desired. Often, a final coat of wax is applied over the finish to add a degree of protection.

.jpg)

French polishing is a finishing method of applying many thin coats of shellac using a rubbing pad, yielding a very fine glossy finish.

Ammonia fuming is a traditional process for darkening and enriching the color of white oak. Ammonia fumes react with the natural tannins in the wood and cause it to change colours.[24] The resulting product is known as "fumed oak".

Types of finishes

There are three major types of finish:[25]

- Evaporative

- Reactive

- Coalescing

Wax is an evaporative finish because it is dissolved in turpentine or petroleum distillates to form a soft paste. After these distillates evaporate, a wax residue is left over.

Reactive finishes may use solvents such as white spirits and naphtha as a base. Varnishes, linseed oil and tung oil are reactive finishes, meaning they change chemically when they cure, unlike evaporative finishes. This chemical change is typically a polymerisation, and the resultant material is less readily dissolved in solvents .

Tung oil and linseed oil are reactive finishes that cure by reacting with oxygen, but do not form a film.

Water based finishes generally fall into the coalescing category.

Comparison of different clear finishes

Clear finishes are intended to make wood look good and meet the demands to be placed on the finish. Choosing a clear finish for wood involves trade-offs between appearance, protection, durability, safety, requirements for cleaning, and ease of application. The following table compares the characteristics of different clear finishes. 'Rubbing qualities' indicates the ease with which a finish can be manipulated to deliver the finish desired. Shellac should be considered in two different ways. It is used thinned with denatured alcohol as a finish and as a way to manipulate the wood's ability to absorb other finishes. The alcohol evaporates almost immediately to yield a finish that will attach to virtually any surface, even glass, and virtually any other finish can be used over it.

-

Linseed oil

-

Shellac

-

2:1 ratio of beeswax and carnauba wax

-

No finish

-

Molten bee wax

-

Shellac and linseed oil

-

Acrylic paint

-

Alkyd

-

Spar varnish

-

Tung oil

-

Tung oil and linseed oil

-

Acrylic varnish

| Appearance | Protection | Durability | Safety | Ease of Application | Reversibility | Rubbing Qualities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wax | Dull, even sheen unless spit polished | Short Term | Needs frequent reapplication | Safe when solvents in paste wax evaporate | Difficult on bare wood | Difficult. Solvents thin wax causing it to penetrate deeper. Sanding creates heat. Scraping recommended | Needs to be buffed for low sheen, buffed with damp pad for high gloss |

| Shellac | From virtually clear (super blond) to a rich orange (garnet) | Fair against water, poor solvent protection | Durable | Safe when solvent evaporates, used as food and pill coating | Clogs spray equipment. Quick solvent flash time makes brushing difficult. Ox or badger/skunk hair brush recommended. Easy to pad, however French Polish is difficult | Completely reversible using alcohol | Excellent |

| Nitrocellulose lacquer | Transparent, good gloss | Decent protection | Soft and somewhat durable | Uses toxic solvents. Good protection is needed, especially if painted | Requires equipment. | Reversible with proper solvents | Excellent soft finish |

| Pre-Cat lacquer | Transparent, all sheens from 5% to 90% | Good general protection against wet and dry heat. | Meets UK and European standards for "general use". | Uses toxic solvents. Spray booth is needed. | Spray application only. | Non-Reversible after 5 days | Excellent general furniture finish used extensively outside USA |

| Conversion varnish | Transparent, good gloss | Excellent protection against many substances | Hard and durable | Uses toxic solvents, including toluene. Breathing protection is needed | Requires spray equipment. Used in professional shops only | Difficult to reverse | Excellent hard finish |

| Boiled linseed oil | Yellow warm glow, pops grain1, darkens with age | Very little | Little | Relatively safe, metallic driers are poisonous, rags may spontaneously combust | Easy, but cure time can be upward of 30 days | Difficult. All saturated wood needs to be removed (planing/sanding/scraping) | Dries hard, can be buffed to high gloss |

| Tung oil | Warm glow, pops grain1, lighter than linseed | Water resistant | Poor | Relatively safe when fully cured. Pure tung oil contains no metallic dryers. Many products labeled tung oil are oil/varnish blends | Difficult. Sanding is required between coats and a partial cure is necessary. Very long finishing schedule for sufficient amount of coats | Difficult. All saturated wood needs to be removed (planing/sanding/scraping) | Dries hard, can be buffed to high gloss |

| Alkyd varnish | Not as transparent as lacquer, yellowish/orange tint | Good protection | Durable | Relatively safe, uses petroleum based solvents | Brush or spray. Brushing needs good technique to avoid bubbles & streaks | Can be stripped using paint removers | Fair |

| Polyurethane varnish | Slight ambering, comes in a variety of sheen | Excellent protection against many substances, tough finish | Durable after approx. 7 day curing period | Relatively safe, uses petroleum based solvents | Very easy when thinned and wiped on. Also brushes and sprays well | Can be stripped using paint removers | Easy to rub out with steel wool or synthetic pads to reduce sheen. Because it is soft, it cannot be buffed to a high gloss |

| Water-based polyurethane | Transparent | Good protection. Newer products (2009) also UV stable when noted | Durable after approx. 10 day curing period | Safer than oil-based, fewer volatile organic compounds | Brush or spray. Fast drying demands care in application techniques | Can be stripped using paint removers | Excellent. Acrylic finishes are very hard and can be buffed to an extreme gloss. Use a release agent |

| 2-Part polyurethane | Transparent | Stronger protection than regular polyurethane varnish | Durable once cured, generally less than an hour | low or free of VOCs, nonreactive when cured | generally sprayed, equipment must be cleaned of any mixed product immediately | Irreversible | Sands easily. Sanding not needed between coats |

| Oil-varnish blends (i.e. Danish Oil, Teak oil, "tung oil finish") | Enhances natural figure like a drying oil, but easier to apply and more protective. | Low, but more than pure oil finishes | Fairly durable but not recommended for heavy use items such as table tops | Relatively safe, uses petroleum based solvents | Easy, apply with rags and wipe off. Too many applications can result in sticky build up | Difficult. All saturated wood needs to be removed (planing/sanding/scraping) | Dries hard. can be buffed to a matte finish or to a gloss. Often top coated with paste wax for extra protection |

| Epoxy resin | Thick, high-gloss, and transparent. Some formulations can cloud or yellow with UV exposure | High level of protection | Flexible and durable | Safe when cured | Easy pour-on application for flat surfaces, difficult to apply evenly on more complicated shapes | Cleanable with acetone when liquid. Irreversible once cured | flexibility makes sanding difficult but possible |

1 accentuates visual properties due to differences in wood grain.

Automated wood finishing methods

Manufacturers who mass-produce products implement automated flatline finish systems. These systems consist of a series of processing stations that may include sanding, dust removal, staining, sealer and topcoat applications. As the name suggests, the primary part shapes are flat. Liquid wood finishes are applied via automated spray guns in an enclosed environment or spray cabin. The material then can enter an oven or be sanded again depending on the manufacturer’s setup. The material can also be recycled through the line to apply another coat of finish or continue in a system that adds successive coats depending on the layout of the production line. The systems typically used one of two approaches to production.

Hangline approach

In the hangline approach, wood items being finished are hung by carriers or hangers that are attached to a conveyor system that moves the items overhead or above the floor space. The conveyor itself can be ceiling mounted, wall mounted or supported by floor mounts. A simple overhead conveyor system can be designed to move wood products through several wood finishing processes in a continuous loop. The hangline approach to automated wood finishing also allows the option of moving items up to warmer air at the ceiling level to speed up drying process.

Towline approach

The towline approach to automating wood finishing uses mobile carts that are propelled by conveyors mounted in or on the floor. This approach is useful for moving large, awkward shaped wood products that are difficult or impossible to lift or hang overhead, such as four-legged wood furniture. The mobile carts used in the towline approach can be designed with top platens that rotate either manually or automatically. The rotating top platens allow the operator to have easy access to all sides of the wood item throughout the various wood finishing processes such as sanding, painting and sealing.

See also

References

- ↑ Whaler, J.H. (1972). Furniture finishing textbook. Nashville: Production Publishing Company. p. 3.

- ↑ Cox, Robert M. (2003). Building an industrial wood finish. Madison: Forest Products Society. p. 11. ISBN 1-892529-30-0.

- ↑ Gibbia, S.W. (1981). Wood finishing and refinishing. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 9. ISBN 0-442-24708-7.

- ↑ Jaić, Milan, and Tanja Palija. "The impact of the top coating on the mechanical properties of lacquered wood surfaces." Glasnik Sumarskog fakulteta

- ↑ Bongova, M.; Urgela, Stanislav (1999-01-01). "Surface coating influence on elastic properties of spruce wood by means of holographic vibration mode visualization" 3820: 103–110. doi:10.1117/12.353047.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hatchard, Den (1992). Wood Finishing: Step-by-step techniques. Ramsbury, Marlborough: The Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1852235826.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Flexner, Bob (1999-01-01). Understanding Wood Finishing: How to Select and Apply the Right Finish. Reader's Digest. ISBN 9780762101917.

- ↑ Iseghem, Lawrence C. Van (June 2006). "Wood Finishing with UV-Curable Coatings" (PDF). RADTECH REPORT.

- ↑ Newell, Adnah Clifton (1940-01-01). Coloring, Finishing and Painting Wood. Manual arts Press.

- ↑ Vanderwalker, Fred Norman (1940-01-01). Wood Finishing, Plain and Decorative: Methods, Materials, and Tools for Natural, Stained, Varnished, Waxed, Oiled, Enameled, and Painted Finishes. Antiqued, Stippled, Streaked and Rough Glazed Finishes. Stain Making Formulas. F. J. Drake & Company.

- ↑ Crump, Derrick (1992-01-01). The Complete Guide to Wood Finishes. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671796693.

- ↑ Sandermann, Wilhelm; Dietrichs, Hans-Hermann; Puth, Martin (1960-02-01). "Über die Trocknungsinhibierung von Lackanstrichen auf Handelshölzern". Holz als Roh- und Werkstoff (in German) 18 (2): 63–75. doi:10.1007/BF02615619. ISSN 0018-3768.

- ↑ Farmer, Robert Harvey (1967-06-01). Chemistry in the utilization of wood. Pergamon Press.

- ↑ Kumar, R. N.; Al-Mahdi, Haider Osma; Scherzer, T.; Sonntag, J. von (2002-06-26). "Influence of Wood Extracts on the Uv Curing of Acrylate Coatings". Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A 39 (7): 657–666. doi:10.1081/MA-120004510. ISSN 1060-1325.

- ↑ Evans, Philip D.; Cullis, Ian. "A Note on the Effect of Wood Moisture Content and Clear Coating on the Color of Veneer Panels Stained with Solvent-Borne Stain". Forest Products Journal 60 (3): 273–275. doi:10.13073/0015-7473-60.3.273.

- ↑ Press, Taunton; Woodworking, Fine (1999-01-01). Finishes & Finishing Techniques: Professional Secrets for Simple and Beautiful Finishes from Fine Woodworking. Taunton Press. ISBN 9781561582983.

- ↑ "Case study project: The use of low-VOC/HAP coatings at wood furniture manufacturing facilities. Report for March 1995 March 1999" (PDF). National Service Center for Environmental Publications (NSCEP). Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- ↑ Parikka-Alhola, Katriina (2008-12-01). "Promoting environmentally sound furniture by green public procurement". Ecological Economics 68 (1–2): 472–485. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.05.004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Nagyszalanczy, Sandor (1997-01-01). The Wood Sanding Book: A Guide to Abrasives, Machines, and Methods. Taunton Press. ISBN 9781561581757.

- ↑ Nakamura, G-I, Takachio, H. 1961. An experiment on the roughness and stability of sanded surface. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 7:41-45.

- ↑ Marra, G.G. 1943. An analysis of the factors responsible for raised grain on the wood of oak following sanding and staining. Transactions of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers 65:177-185.

- ↑ Koehler, A. 1932. Some observations on raised grain. Transactions of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers 54:27-30.

- ↑ Hayward, Charles H. (1974-09-01). Staining and Polishing. Sterling Publishing Company, Incorporated. ISBN 9780877490074.

- ↑ "Fuming white oak".

- ↑ http://www.ukworkshop.co.uk/forums/difference-between-lacquer-and-varnish-t39510.html

- Michael Dresdner (1992). The Woodfinishing Book. Taunton Press. ISBN 1-56158-037-6

- Bob Flexner (1994). Understanding Wood Finishing: How to Select and Apply the Right Finish. Rodale Press ISBN 0-87596-566-0

External links

- Shellac Application

- Finishes on Antique Wood Furniture

- To Refinish or Not to Refinish (Antique Furniture)

- Finishing for First-Timers

- Oil Finishes

- Homeshop finishes that work