Grand Army of the Republic

The "Grand Army of the Republic" (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (U.S. Navy), Marines and the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service who served in the American Civil War for the Northern/Federal forces. Founded in 1866 in Decatur, Illinois, and growing to include hundreds of posts (local community units) across the nation, (predominately in the North, but also a few in the South and West), it was dissolved in 1956 when its last member, Albert Woolson (1850–1956) of Duluth, Minnesota, died. Linking men through their experience of the war, the G.A.R. became among the first organized advocacy groups in American politics, supporting voting rights for black veterans, promoting patriotic education, help to make Memorial Day a national holiday, lobbying the United States Congress to establish regular veterans' pensions, and supporting Republican political candidates. Its peak membership, at more than 490,000, was in 1890, a high point of various Civil War commemorative and monument dedication ceremonies. It was succeeded by the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (S.U.V.C.W.), composed of male descendants of Union Army and Union Navy veterans.

History

After the end of American Civil War, various state and local organizations were formed for veterans to network and maintain connections with each other. Many of the veterans used their shared experiences as a basis for fellowship. Groups of men began joining together, first for camaraderie and later for political power. Emerging as most influential among the various organizations during the first post-war years, was the Grand Army of the Republic, founded on April 6, 1866, on the principles of "Fraternity, Charity and Loyalty," in Decatur, Illinois, by Dr. Benjamin F. Stephenson.

The G.A.R. initially grew and prospered as a de facto political arm of the Republican Party during the heated political contests of the Reconstruction era. The commemoration of Union Army and Navy veterans, black and white, immediately became entwined with partisan politics. The G.A.R. promoted voting rights for then called "Negro"/"Colored" black veterans, as many white veterans recognized their demonstrated patriotism and sacrifices, providing one of the first racially integrated social/fraternal organizations in America. Black veterans, who enthusiastically embraced the message of equality, shunned black veterans' organizations in preference for racially inclusive/integrated groups. But when the Republican Party's commitment to reform in the South gradually decreased, the G.A.R.'s mission became ill-defined and the organization floundered. The G.A.R. almost disappeared in the early 1870s, and many state-centered divisions - named "departments" and local posts ceased to exist.[2]

In his General Order No. 11, dated May 5, 1868, first G.A.R. Commander-in-Chief, General John A. Logan declared May 30 to be Memorial Day (also referred to for many years as "Decoration Day"), calling upon the G.A.R. membership to make the May 30 observance an annual occurrence. Although not the first time war graves had been decorated, Logan's order effectively established "Memorial Day" as the day upon which Americans now pay tribute to all our nation's war casualties, missing-in-action, and deceased veterans. As decades passed, similarly-inspired commemorations also spread across the South as "Confederate Memorial Day" or "Confederate Decoration Day", usually in April, led by organizations of Southern soldiers in the parallel United Confederate Veterans.[3]

In the 1880s, the Union veterans organization revived under new leadership that provided a platform for renewed growth, by advocating Federal pensions for veterans. As the organization revived, black veterans joined in significant numbers and organized local posts. The national organization, however, failed to press the case for similar pensions for black soldiers. Most black troops never received any pension or remuneration for wounds incurred during their Civil War service.[4]

The G.A.R. was organized into "Departments" at the state level and "Posts" at the community level, and military-style uniforms were worn by its members. There were posts in every state in the U.S., and several posts overseas.[4]

The pattern of establishing departments and local posts was later used by other American military veterans' organizations, such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars (organized originally for Spanish–American and Philippines Wars [formerly referred to as the "Philippine Insurrection"]) and the later American Legion (for the First World War and later expanded to include subsequent World War II, Korean, Vietnam and Middle Eastern wars).

The G.A.R.'s political power grew during the latter part of the 19th century, and it helped elect several United States presidents, beginning with the 18th, Ulysses S. Grant, and ending with the 25th, William McKinley. Five Civil War veterans and members (Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Benjamin Harrison, and McKinley) were elected President of the United States; all were Republicans. (The sole post-war Democratic president was Grover Cleveland, the 22nd and 24th chief executive.) For a time, candidates could not get Republican presidential or congressional nominations without the endorsement of the G.A.R. veterans voting bloc.

With membership strictly limited to "veterans of the late unpleasantness," the GAR encouraged the formation of Allied Orders to aid them in various works. Numerous male organizations jousted for the backing of the GAR, and the political battles became quite severe until the GAR finally endorsed the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War as its heir. Although a male organization, the GAR admitted a woman member in 1897. Sarah Emma Edmonds served in the 2nd Michigan Infantry as a disguised man named Franklin Thompson from May 1861 until April 1863. In 1882, she collected affidavits from former comrades in an effort to petition for a veteran's pension which she received in July 1884. Edmonds was only a member for a brief period as she died September 5, 1898; however she was given a funeral with military honors when she was reburied in Houston in 1901.[5]Another female admitted to the GAR was Kady Brownell, who served in the Union Army with her husband Robert at the First Battle of Bull Run and the Battle of New Berne. Kady was admitted as a member in 1870 to the Post Elias Howe Jr. in Bridgeport, Connecticut.[6]

The GAR reached its largest enrollment in 1890, with 490,000 members. It held an annual "National Encampment" every year from 1866 to 1949. At that final encampment in Indianapolis, Indiana, the few surviving members voted to retain the existing officers in place until the organization's dissolution; Theodore Penland of Oregon, the GAR's Commander at the time, was therefore its last. In 1956, after the death of the last member, Albert Woolson, the GAR was formally dissolved.[2]

Memorials, honors and commemorations

Memorials to the Grand Army of the Republic include a commemorative postage stamp, a U.S. highway, and physical memorials in numerous communities throughout the United States:

- U.S. Route 6 is known as the Grand Army of the Republic Highway for its entire length.[7]

- At the final encampment in 1949, the Post Office Department issued a three-cent commemorative postage stamp.[8] Two years later, it printed a virtually identical stamp for the final reunion of the United Confederate Veterans.[9]

- Modesto, California: Memorial lot in Modesto Pioneer Cemetery contains 36 graves, a wooden cenotaph and two cannons were erected as a monument in 1907. The wooden cenotaph was replaced with a granite obelisk in 1924.[10]

- Oakland, California: GAR plot and monument dedicated in 1893 in Mountain View Cemetery, 5000 Piedmont Avenue.[11]

- Sacramento, California: GAR memorial and many grave sites in the Sacramento Historic City Cemetery (aka Old City Cemetery).[12]

- San Jose, California: GAR lot in Oak Hill Cemetery.[13]

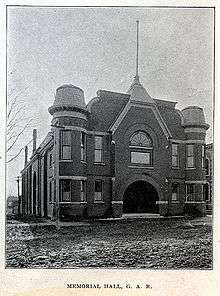

- Rockville, Connecticut: The New England Civil War Museum is maintained by Alden Skinner Camp 45 Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. The museum is within Memorial Hall, which was dedicated to the GAR veterans by the former city of Rockville.[14]

- Washington, D.C.: A memorial honoring founder Benjamin F. Stephenson, M.D., stands near the National Archives Building and the Navy Memorial (38°53′37″N 77°01′18″W / 38.893565°N 77.021558°W[15][16]). The GAR Memorial Foundation erected the monument using funds appropriated by the U.S. Congress in 1907 and dedicated the work in 1909.[17]

- Chicago, Illinois:

- GAR memorial and several gravesites in Union Ridge Cemetery in the Norwood Park neighborhood.[18]

- The current Chicago Cultural Center was formerly the dual-purposed Chicago Public Library and GAR Meeting Hall. Completed in 1897, it occupies property on Michigan Avenue at Randolph Street donated by the GAR.[19]

- Decatur, Illinois: GAR section with approximately 570 graves and monument in Greenwood Cemetery[20]

- Hoopeston, Illinois: GAR memorial and many gravesites Floral Hill Cemetery.

- Minier, Illinois: GAR monument erected in 1888 by the John Hunter GAR Post 168[21]

- Murphysboro, Illinois: A cemetery with the graves of several GAR members who were former slaves originally from Tennessee is southwest of the town.

- Palatine Township, Illinois: re-dedicated the Grand Army Memorial Plot at Hillside Cemetery on August 16, 2015.[22]

- River Forest, Illinois: Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Woods which is part of the Forest Preserves of Cook County.

- Springfield, Illinois:

- Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Museum, located at 629 South 7th Street is owned and maintained by the Woman's Relief Corps Auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic.[23]

- The Daughters of Union Veterans of the Civil War donated a sundial that was dedicated on the grounds of the Illinois State Capitol September 8, 1940, during the 74th Encampment of the GAR.[24]

- Watseka, Illinois: GAR Cemetery, established for the Williams Post 25, has a memorial and statue as prominent features at the entrance.<ref name=""Watseka">"GAR Cemetery". Find A Grave. Retrieved 2011-05-31.</ref>

- Valparaiso, Indiana: The Memorial Opera House was constructed by the local GAR chapter in 1893.[25]

- Des Moines, Iowa: In 1922, a banner created for the GAR encampment was declared a permanent memorial and suspended in the rotunda of the Iowa State Capitol.[26] A sundial was dedicated to the GAR on grounds of the Iowa State Capitol during the 1938 encampment.[27]

- Eldora, Iowa: GAR memorial of a metal soldier atop a granite base costing $3,000 was erected in 1885 in the center of the town square. It was relocated on the site in 1890 to accommodate construction of the courthouse. It has since been relocated to a site east of the courthouse and restored in 1985.[28]

- Red Oak, Iowa: GAR memorial of a bronze soldier atop a granite base was dedicated in 1907 near grave sites in Evergreen Cemetery.[29]

- Mt. Pleasant, Iowa: GAR monument and grave sites in the pioneer Hickory Grove Cemetery, junction of Hwy 218 & 185th St.[30]

- Redfield, Iowa: The Marshall GAR Hall was restored in 2008 and houses a small museum.[31]

- Waterloo, Iowa: The Grand Army of the Republic meeting hall has been restored and is operated as a meeting hall and museum by the City of Waterloo. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.[32][33]

- Baxter Springs, Kansas: GAR monument and 163 gravesites in the Baxter Springs City Cemetery[34]

- Topeka, Kansas: The GAR Memorial Hall at 120 SW 10th Avenue was dedicated May 27, 1914, housed the Kansas State Historical Society until 1995 when the society moved to larger quarters. After restoration, the structure became home to the Attorney General and Secretary of State offices in 2000.[35]

- Covington, Kentucky: GAR Monument in the Linden Grove Cemetery erected in 1929.[36]

- Chalmette, Louisiana: Chalmette National Cemetery in Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve contains a monument and the graves of approximately 12,000 Union Soldiers from the Civil War[37]

- Baltimore, Maryland: A sundial at Warren Avenue and Henry Street in the Federal Hill neighborhood was dedicated in 1933.[38]

- Rockland, Massachusetts: Hartstuff Post 74 was dedicated January 30, 1900. Portions of the wooden structure were restored between 1990 and 1999 and the structure is currently home of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War Camp 50.[39]

- Algonac, Michigan: Bronze statue of a soldier on a granite base was erected in 1905 in Boardwalk Park on St. Clair River Drive.[40]

- Bay City, Michigan:

- A monument of Whitney granite on a base of the same was erected in 1893 in Pine Ridge Cemetery in a section dedicated as Soldier's Rest. Pine Ridge Cemetery is located on the SE corner of Tuscola and Ridge Rd[41]

- In 1902, an 8-inch Howitzer siege gun cannon was added to the Soldier's Rest section of Pine Ridge to guard the soldiers.[42]

- Detroit, Michigan: Grand Army of the Republic Building was completed in 1890 as a meeting place for the local chapter of the GAR. When membership dwindled in the 1930s, the group deeded the property to the City of Detroit who paid a portion of the construction costs. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986 and was vacant for many years.[43] In November 2011, the software company Mindfield acquired the building and, through the summer of 2013, spent over $1,000,000 on restoration.[44] In addition to Mindfield, the building now houses an upscale restaurant.[45]

- Flint, Michigan: Two Parrott rifles occupy the lawn of the Genesee County Courthouse. In 2003, the Governor Henry H. Crapo Camp of SUVCW restored the bases and held a re-dedication ceremony.[46]

- Grand Rapids, Michigan

- A zinc fountain depicting a soldier at parade rest atop a carved column was dedicated in 1885 at the intersection of Fulton, Monroe and Division. It was restored and rededicated in October 2003.[47]

- Oak Hill Cemetery at 1100 Eastern Avenue, SE contains an obelisk and the graves of several members of the Custer Post No. 5.[48]

- Bemidji, Minnesota: GAR memorial in Greenwood Cemetery.[49]

- Detroit Lakes, Minnesota: GAR Park, 317 Washington Avenue. The GAR Park was rededicated on April 15, 2015.[50]

- Grand Meadow, Minnesota: GAR Hall/Museum. Booth Post No. 130 was once a meeting hall for members of the Grand Army of the Republic. The hall is believed to be one of only two remaining in Minnesota and is located on South Main Street between First Avenue SW and Second Avenue SW. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places because of its architectural and social significance.[51]

- Hastings, Minnesota: Peller Post 89 purchased one-half acre of land for a cemetery in 1905. It holds graves of Civil War and Spanish–American War veterans.[52] In 1998, local VFW post 1210 restored the cemetery.[53]

- Litchfield, Minnesota: The hall of Frank Daggett Post 35 has been preserved and houses a GAR museum.[53]

- St. Paul, Minnesota: A memorial obelisk capped by a bronze statue stands at the intersection of John Ireland Boulevard and Summit Avenue. The statue gazes toward the capitol building to the east and was erected in 1903 at a cost of $9,000. It was created by artist John K. Daniels and bears a dedication to "Josias R. King the first man to volunteer in the 1st MN infantry" and commemorates all who fought.[54]

- Carthage, Missouri: Park Cemetery contains a lot with several burials from the Stanton Post No. 16 with a large granite monument[55]

- Laclede, Missouri: Grove and Cole Streets; Bronze soldier atop a granite base inscribed with a dedication to the Phil Kearny Post No. 19[56]

- Omaha, Nebraska: Forest Lawn Memorial Park holds a GAR memorial and many grave sites.[57]

- South Lyndeborough, New Hampshire: The Hartshorn Memorial Cannon was named and dedicated by the Harvey Holt Post, Grand Army of the Republic, in 1902. The cannon was previously located outside the GAR's headquarters, Citizens' Hall, before being moved to the village common in 1934.[58]

- Asbury Park, New Jersey: Monument at Grand and Cookman Avenues erected by C.K. Hall Post 41.[59]

- Atlantic City, New Jersey: Monument at Providence and Capt. O'Donnell Parkway erected by the Joe Hooker Post 32.[59]

- Camden, New Jersey: Plot of the William B. Hatch Post 37 with monument in Evergreen Cemetery.[59]

- Egg Harbor, New Jersey: General Stahel Post 62 plot in the Egg Harbor City Cemetery.[59]

- Jersey City, New Jersey:

- Bayview – New York Bay Cemetery — Monument and plot of Van Houten Post #3 and Ladies Relief Post #16, 44 graves including William Winterbottom, Medal of Honor recipient.[60][61]

- Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Goddess of Victory bronze by Philip Martiny, at City Hall, 280 Grove Street[62]

- Manchester Township, New Jersey: GAR memorial at Oakdale Street and Wellington Avenue.[59]

- Port Norris, New Jersey: GAR Cemetery of the John Shinn Post 6.[59]

- Toms River, New Jersey: Monument at Wellington Avenue and Oakdale Street consisting of a small peristyle, flagpole and two cannons[63]

- Washington, New Jersey: Inscribed windows commemorating the John F. Reynolds GAR Post 66 donated during construction of the First Methodist Episcopal Church (now The United Methodist Church in Washington) in 1896.

- Bath, New York: Memorial in Nondaga Cemetery, erected by Custer Post 81 in 1916 in observance of Memorial Day.[64]

- Buffalo, New York: Soldiers and Sailors Monument dedicated in Lafayette Square in 1884. By 1889, the monument began to list and was reconstructed.[65]

- New York, New York:

- Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn was dedicated in 1926 and forms the entrance to Prospect Park. It contains a triumphal arch and other monuments.[66]

- In Midtown Manhattan, Grand Army Plaza contains a statue of General Sherman.

- In Upper Manhattan, the west flagpole on Low Plaza at the entrance of Low Memorial Library on Columbia University's Morningside Heights campus was donated by the Lafayette Post of the Grand Army of the Republic in 1898 and bears the inscription "Love, Cherish, Defend it."[67] (The east pole was donated by the class of 1881 on its twenty-fifth anniversary in 1906.[68])

- Mount Olivet Cemetery in Queens contains the burial lot of the Robert J. Marks Post # 560 of the GAR. In the lot are the graves of 25 veterans, 17 wives and a monument.[69]

- Devils Lake, North Dakota: GAR lot and monument in Devils Lake Cemetery.[70]

- Columbus, Ohio: The Daughters of the Union dedicated a sundial on the grounds of the Ohio State House in 1941, the 75th anniversary of the GAR.[71]

- Portland, Oregon: Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery. Salmon Brown, son of the famous abolitionist John Brown (of the song "John Brown's Body") is buried there.[72]

- Carnegie, Pennsylvania: When the Andrew Carnegie Free Library and Music Hall was constructed in 1901, it included a room to house the Captain Thomas Espy Post Number 153 of the GAR. The room is now preserved with artifacts and records left when the last post member died in the 1930s.[73]

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: GAR museum and library maintained by the Philadelphia Camp Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War in the John Ruan House. The archive holds numerous GAR post records and the museum has a variety of civil war artifacts.[74]

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Soldiers & Sailors Hall dedicated in 1910 as a GAR memorial.[75]

- Titusville, Pennsylvania:, The original charter and other documents from Cornelius S. Chase Post 50, including its handwritten by-laws, are on display at the Cleo J. Ross Post 368 American Legion in Titusville.

- Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: G. A. R. Memorial Junior Senior High School[76]

- Cleveland, Tennessee: The GAR Monument at Fort Hill Cemetery is only one of three GAR memorials in Tennessee.[77]

- Vermont: State Route 15 is known as the Grand Army of the Republic Highway.[78]

- Rutland, Vermont: Memorial Hall dedicated in 1899, served as the library until the 1930s[79]

- Seattle, Washington: The city's five GAR posts established Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery on Capitol Hill, just north of Lake View Cemetery in 1895. In 1922, the groups ceded control to the Seattle Parks Department.[80]

- Snohomish, Washington: GAR Morton Post 110 established Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery was established in 1889 at 8602 Riverview Road. It contains the graves of 200 Civil War veterans.[81] On May 29, 1914, the community dedicated a monument at the northwest corner of the cemetery consisting of an obelisk and statue of a soldier on a base.[82]

- Tacoma, Washington: Oakwood Hill Cemetery has large section containing several hundred GAR veterans who were members of the Custer Post and their wives.[83]

- Columbus, Wisconsin: A bronze figure of a soldier atop a square granite column was erected by the H.M. Brown Post 146 of the GAR at the intersection of West James Street (Highway 60) and Dickason Boulevard (Highway 16), adjacent to the City Hall.[84]

- Madison, Wisconsin: Grand Army of the Republic Conference Room at the Wisconsin State Capitol.[85]

- Necedah, Wisconsin: Flagpole and inscribed tablet in Bay View Cemetery; North Main and Maple Streets[86]

State posts

With the exception of Hawaii, every state had GAR "posts" (forerunners of modern American Legion Halls or VFW Halls), even those of the former Confederacy. The posts were made up of local veterans, many of whom participated in local civic events. As Civil War veterans died or were no longer able to participate in GAR activities, posts consolidated or were disbanded.[87] Posts were assigned a sequential number based on their admission into the state's GAR organization, and most posts held informal names which honored comrades, battles, or commanders; it was not uncommon to have more than one post in a state honoring the same individual (such as Abraham Lincoln) and posts often changed their informal designation by vote of the local membership.

Many states held annual encampments based on the national encampment model. These state encampments filled both a social and political function, as state GAR leaders were elected, political platforms voted upon, and veterans' issues were discussed openly. Much like the national organization, state GAR leaders could wield strong political influence.

See:

- List of Grand Army of the Republic Posts in Kansas

- List of Grand Army of the Republic Posts in Kentucky

In popular culture

John Steinbeck's East of Eden features several references to the Grand Army of the Republic. Despite having very little actual battle experience during his brief military career, cut short by the loss of his leg, Adam Trask's father Cyrus joins the GAR and assumes the stature of "a great man" through his involvement with the organization. At the height of the GAR's influence in Washington, he brags to his son:

| “ | I wonder if you know how much influence I really have. I can throw the Grand Army at any candidate like a sock. Even the President likes to know what I think about public matters. I can get senators defeated and I can pick appointments like apples. I can make men and I can destroy men. Do you know that? | ” |

Later in the book, references are made to the graves of GAR members in California in order to emphasize the passage of time.[88]

Another Nobel Prize winning author, Sinclair Lewis, refers to the GAR in his acclaimed novel Main Street.[89]

Charles Portis's classic novel, True Grit, makes reference to the GAR.[90]

The GAR is briefly mentioned in William Faulkner's novel, The Sound and the Fury.[91]

Willa Cather's short story The Sculptor's Funeral briefly references the GAR.[92]

The GAR is mentioned in the seldom sung second verse of the patriotic song You're a Grand Old Flag.[93]

The GAR is referenced in John McCrae's poem He Is There! which was set to music in 1917 by Charles Ives as part of his cycle Three Songs of the War.[94]

The clone troopers of Star Wars and the army they composed, the Grand Army of the Republic, are both first mentioned in George Lucas's film Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones. The title of "Grand Army of the Republic" for the clone army appears across various other Star Wars media. This clone army first fought in a war that was also their namesake, the Clone Wars, as the largest military force for the Galactic Republic in a civil war against the Confederacy of Independent Systems, who themselves employed a mass-produced army, the Separatist Droid Army.

In Ward Moore's 1953 alternate history novel Bring the Jubilee, the South won the Civil War and became a major world power while the rump United States was reduced to an impoverished dependence. The Grand Army of the Republic is a nationalistic organization working to restore the United States to its former glory through acts of sabotage and terrorism.[95]

See also

- Austin Conrad Shafer, California Department official, with Department commander (photo)

- Charles Sumner Post No. 25, Grand Army of the Republic

- Grand Army of the Republic Hall (disambiguation)

- Grand Army of the Republic Highway

- G. A. R. Memorial Junior Senior High School, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania

- Hamilton County Memorial Building, (Cincinnati, Ohio)

- Joel Minnick Longenecker

- List of Grand Army of the Republic Commanders-in-Chief

- National Association of Army Nurses of the Civil War

- Russell A. Alger

- Sons of Confederate Veterans

- Sons of Union Veterans

- The American Legion

- United Confederate Veterans

- Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States

References

- ↑ 10 U.S.C. § 1123

- 1 2 Knight, Glenn B. "Brief History of the Grand Army of the Republic". suvcw.org. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- ↑ John E. Gilman (1910). "The Grand Army of the Republic". civilwarhome.com. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- 1 2 "A Brief History of the Grand Army of the Republic". Grand Army of the Republic Museum and Library. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ↑ "Sarah Emma Edmonds, Private, December 1841–September 5, 1898". Civil War Trust. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- ↑ "A female comrade of the Grand Army". New York Herald. 16 September 1870. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Richard F. Weingroff (July 27, 2009). "U.S. 6-The Grand Army of the Republic Highway". Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ A. Gibson, Gary (1999). "Remembering the Grand Army of the Republic Fifty Years Later". Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

B. "G.A.R. Issue". National Postal Museum. Retrieved Jan 11, 2014. - ↑ "U.S. Stamps 1951". stampscatalog.info. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ↑ "Grand Army of the Republic". The Historical Marker Database. 29 May 2009. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ "GAR Plot". Mountain View Cemetery. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ "Sacramento Historic City Cemetery Self-Guided Tour". OldCityCemetery.com. 2005. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ↑ "Events". United Veterans Council of Santa Clara County. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ "New England Civil War Museum". NewEnglandCivilWarMuseum.com. 4 December 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ↑ Hybrid satellite image/street map of Stephenson GAR Memorial in Washington, D.C., from WikiMapia

- ↑ "Stephenson Grand Army of the Republic Memorial". dcmemorials.com. 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ "Stephenson Grand Army of the Republic Memorial". Smithsonian American Art Museum, Art Inventories Catalog. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ "Union Ridge Cemetery". Find A Grave. 5 July 2010. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ "The People's Palace: The Story of the Chicago Cultural Center". CityofChicago.org. 1999. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ↑ Lowe, Kenneth (27 May 2011). "Wet conditions fail to stop Greenwood Cemetery ceremony". Herald & Review (Decatur). Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "Civil War Monument, Minier, IL". Waymarking.com. 28 July 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "GAR Dedication Ceremony to Include Civil War Re-Enactors, Historic Canon Firing at Hillside Cemetery". Palatine Patch. July 9, 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- ↑ "National Headquarters GAR Museum". Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Illinois State Capitol-A Walking Tour" (PDF). Illinois Secretary of State. May 2001. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Memorial Opera House". Valparaiso Memorial Opera House. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "The Capitol Today-Third Floor". Iowa Legislature. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "Iowa Profile". State of Iowa. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "History: The Civil War Monument". Hardin County, Iowa. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ↑ "Montgomery County: Red Oak". IowaCivilWarMonuments.com. 30 November 2007. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Henry County-Mt. Pleasant". IowaCivilWarMonuments.com. 30 May 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Dallas County-Redfield". IowaCivilWarMonuments.com. 25 May 2008. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Black Hawk County Memorial Hall". Cedarnet.org. June 23, 2004. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ↑ "Black Hawk County Soldiers Memorial Hall". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ↑ "Baxter Springs City Cemetery Soldiers' Lot". cem.va.gov. 6 January 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ↑ "Schmidt, Kobach to commemorate Memorial Hall Anniversary" (Press release). Kansas Attorney General. 12 October 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). Kenton County Public Library. 17 July 1997. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ "Chalmette National Cemetery". Civilwarhome.com. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "Our Fathers Saved Sundial". Monument City Blog. June 16, 2009. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "Hartsuff Post 74 Grand Army of the Republic Hall". Rockland GAR Hall. 18 December 1998. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

- ↑ "Grand Army of the Republic Monument, Algonac, Michigan". Department of Michigan-Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. 19 March 2006. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ "The Soldier's Monument". Bay City Tribune. 19 August 1893. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- ↑ "Now Guards the Soldier's Rest". Bay City Tribune. 9 March 1902. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- ↑ Nolan, Jenny (January 28, 1997). "The Grand Army of the Republic". The Detroit News. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ↑ Austin, Dan (July 5, 2013). "A preservation battle worth fighting". The Detroit Free Press. p. 11A. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- ↑ Rector, Sylvia (February 12, 2015). "G.A.R. Building's Republic restaurant to open next week". The Detroit Free Press. p. D1.

- ↑ "Monuments & Memorials". Governor Henry H. Crapo Camp No. 145. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- ↑ "Civil War Monument". Grand Rapids Historical Commission. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "Custer Post Cenotaph and Burial Area". National Motorcycle Tour. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- ↑ Miron, Molly (31 May 2011). "Service of remembrance held at Greenwood Cemetery". Bemidji Pioneer (bemidjipioneer.com). Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "G.A.R. Park". City of Detroit Lakes. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- ↑ "The Grand Meadow GAR Hall". Mower County Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ↑ "Hastings Veterans Memorials". Minnesota Department of Veterans Affairs. 2010. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- 1 2 "Goodhue County and Minnesota in the G.A.R.". private Anthony. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ "Soldiers and Sailors Monument". City of St. Paul, Minnesota. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ Onions, Thomas (21 March 2010). "Park Cemetery GAR Memorial". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Fischer, Jr., William (27 July 2013). "Phil Kearny Post No. 19 G.A.R. Memorial". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ "Forest Lawn Walking Tour". Forest Lawn Cemetery Association. March 1999. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form-Citizens Hall" (PDF). National Park Service. 9 December 1999. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "New Jersey Civil War Monuments". Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War-New Jersey. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ "Civil War Veterans Buried in G.A.R. Memorial Plot in Bayview-New York Bay Cemetery, Jersey City". The Hudson County Genealogical & Historical Society. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- ↑ "William Winterbottom". Find a Grave. 19 February 2003. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ↑ "Jersey City, New Jersey". Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, New Jersey Department. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ↑ Intile, John (5 May 2011). "Grand Army Of The Republic Memorial". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Mike Foley (29 June 2009). "GAR Monument (photo)". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ↑ Maryinak, Banjamin R. (2001). "The Soldiers & Sailors Monument in Lafayette Square". Buffalo Architecture and History. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ "Grand Army Plaza". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- ↑ "War Memorial Tour of Columbia". Columbia University. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "'81 Endows University Flagstaff, to Mark Fortieth Anniversary". Columbia Alumni News 12 (33). June–July 1921. p. 538. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "History of Mount Olivet Cemetery". MountOlivetCemeteryNYC.com. Retrieved 2011-04-26.

- ↑ "Grand Army of the Republic Monument". Center for Heritage Renewal, North Dakota State University. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ "Grand Army of the Republic Sundial Lest We Forget". State of Ohio. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ↑ "Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery". oregonmetro.gov. January 1, 2005. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ "Espy Post Collection". Andrew Carnegie Free Library and Music Hall. 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

- ↑ "History of the Grand Army of the Republic Museum and Library". Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ Ackerman, Jan (13 August 2001). "Soldiers & Sailors hall winning war on neglect". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ "GAR Memorial Junior Senior High School". publicschoolreview.com. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ↑ "Grand Army of the Republic Monument Fort Hill Cemetery". Southeast Tennessee Tourism Association. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ "Vermont Named State Highways and Bridges" (PDF). Vermont Board of Libraries. April 28, 2008. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "History". Rutland Free Library. 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ "GAR Cemetery Park, Seattle, Washington". The Friends of the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery Park. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ "Civil War Cemetery". City of Snohomish. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ Warner (20 October 2010). "Grand Army of the Republic Monument". Snohomish County Tribune. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ Amzie Browning (31 May 1909). "Browning 004". Tacoma Public Library. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- ↑ "Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Inscription". The Historical Marker Database. 7 March 2010. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

- ↑ "Capitol Exterior". Wisconsin.gov. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ↑ "Soldiers Monument". Historical Marker Database. 8 July 2010. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ "List of posts and location by department". Library of Congress. 2001. Retrieved 2014-07-03.

- ↑ "Steinbeck-East of Eden". edstephan.org. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ↑ Lewis, Sinclair (12 April 2006). "XXXV". Main Street (PDF). Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ↑ Portis, Charles (5 December 2010). True Grit. New York: Overlook Press. Retrieved 2015-01-16. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ The Sound snd the Fury-Glossary. University of Mississippi Press. 1996. p. 54. ISBN 0-87805-936-9. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ↑ "The Sculptor's Funeral". Classic Reader. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ↑ George M. Cohan (1906). "You're a Grand Old Flag (Annotated Music)". Library of Congress Performing Arts Encyclopedia. New York, NY: F. A. Mills. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ↑ "He Is There!". Song of America. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- ↑ Moore, Ward (1 January 2009). Bring the Jubilee. Wildside Press. ISBN 978-1434478535. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

Further reading

- Ainsworth, Scott. "Electoral Strength and the Emergence of Group Influence in the Late 1800s The Grand Army of the Republic." American Politics Research 23.3 (1995): 319–338.

- Dearing, Mary R. Veterans in Politics: The Story of the GAR (1974)

- Gannon, Barbara A. The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic (2011) Online

- Jordan, Brian Matthew. Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War (2015)

- McConnell, Stuart. Glorious Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic, 1865–1900 (U of North Carolina Press, 1997) Online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Army of the Republic. |

- GAR page at Library of Congress

- SUVCW official website

- ASUVCW official website

- DUVCW official website

- Grand Army Museum, Lynn, Massachusetts at Essex National Heritage website

- Theodore Penland grave site

- The GAR medal looks similar to the Medal of Honor in photos or on gravestones, see comparison

- Photographs of Members of the Stevens Post, Seattle, Washington

- Grand Army of the Republic Museum and Library, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- The Grand Army of the Republic. Philip R. Schuyler Post, No. 51 records, including membership records, constitution and by-laws, correspondence and minutes of the Philip R. Schuyler Post No. 51, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- The History Tavern

- Geocache on the Memorial Highway

- Grand Army of the Republic Collection – McLean County Museum of History archives (Illinois)

- Theodore C. Cazeau Grand Army of the Republic Collection – Lavery Library, St. John Fisher College, Rochester NY