Wobble base pair

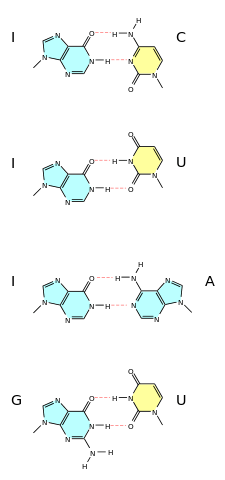

A wobble base pair is a pairing between two nucleotides in RNA molecules that does not follow Watson-Crick base pair rules.[1] The four main wobble base pairs are guanine-uracil (G-U), hypoxanthine-uracil (I-U), hypoxanthine-adenine (I-A), and hypoxanthine-cytosine (I-C). In order to maintain consistency of nucleic acid nomenclature, "I" is used for hypoxanthine because hypoxanthine is the nucleobase of inosine;[2] nomenclature otherwise follows the names of nucleobases and their corresponding nucleosides (e.g., "G" for both guanine and guanosine). The thermodynamic stability of a wobble base pair is comparable to that of a Watson-Crick base pair. Wobble base pairs are fundamental in RNA secondary structure and are critical for the proper translation of the genetic code.

Brief history

In the genetic code, there are 43 = 64 possible codons (tri-nucleotide sequences). For translation, each of these codons requires a tRNA molecule with a complementary anticodon. If each tRNA molecule paired with its complementary mRNA codon using canonical Watson-Crick base pairing, then 64 types (species) of tRNA molecule would be required. In the standard genetic code, three of these 64 mRNA codons (UAA, UAG and UGA) are stop codons. These terminate translation by binding to release factors rather than tRNA molecules, so canonical pairing would require 61 species of tRNA. Since most organisms have fewer than 45 species of tRNA,[3] some tRNA species must pair with more than one codon. In 1966, Francis Crick proposed the Wobble hypothesis to account for this. He postulated that the 5' base on the anticodon, which binds to the 3' base on the mRNA, was not as spatially confined as the other two bases, and could, thus, have non-standard base pairing.[4] Crick creatively named it for the small amount of play that occurs at this third codon position. Movement ("wobble") of the base in the 5' anticodon position is necessary for small conformational adjustments that affect the overall pairing geometry of anticodons of tRNA.[5][6]

As an example, yeast tRNAPhe has the anticodon 5'-GmAA-3' and can recognize the codons 5'-UUC-3' and 5'-UUU-3'. It is, therefore, possible for non-Watson–Crick base pairing to occur at the third codon position, i.e., the 3' nucleotide of the mRNA codon and the 5' nucleotide of the tRNA anticodon.[7]

Wobble hypothesis

These notions led Francis Crick to the creation of the wobble hypothesis, a set of four relationships explaining these naturally occurring attributes.

- The first two bases in the codon create the coding specificity, for they form strong Watson-Crick base pairs and bond strongly to the anticodon of the tRNA.

- When reading 5' to 3' the first nucleotide in the anticodon (which is on the tRNA and pairs with the last nucleotide of the codon on the mRNA) determines how many nucleotides the tRNA actually distinguishes.

If the first nucleotide in the anticodon is a C or an A pairing is specific and acknowledges original Watson-Crick pairing, that is only one specific codon can be paired to that tRNA. If the first nucleotide is U or G, the pairing is less specific and in fact two bases can be interchangeably recognized by the tRNA. Inosine displays the true qualities of wobble, in that if that is the first nucleotide in the anticodon then any of three bases in the original codon can be matched with the tRNA. - Due to the specificity inherent in the first two nucleotides of the codon, if one amino acid codes for multiple anticodons and those anticodons differ in either the second or third position (first or second position in the codon) then a different tRNA is required for that anticodon.

- The minimum requirement to satisfy all possible codons (61 excluding three stop codons) is 32 tRNAS. That is 31 tRNA's for the amino acids and one initiation codon.[8]

tRNA base pairing schemes

The original wobble pairing rules, as proposed by Crick. Watson-Crick base pairs are shown in bold, wobble base pairs in italic:[note 1]

| tRNA 5' anticodon base | mRNA 3' codon base |

|---|---|

| A | U |

| C | G |

| G | C or U |

| U | A or G |

| I | A or C or U |

Revised pairing rules[9]

| tRNA 5' anticodon base | mRNA 3' codon base |

|---|---|

| G | U,C |

| C | G |

| k2C | A |

| A | U,C,(A),G |

| unmodified U | U,(C),A,G |

| xm5s2U,xm5Um,Um,xm5U | A,(G) |

| xo5U | U,A,G |

| I | A or C or U |

Biological importance

Aside from the obvious necessity of wobble, that our bodies have a limited amount of tRNAs and wobble allows for broad specificity, wobble base pairs have been shown to facilitate many biological functions, most clearly proven in the bacteria E. coli. In fact, in a study of E. coli's tRNA for alanine there is a wobble base pair that determines whether the tRNA will be aminoacylated. When a tRNA reaches an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase, the job of the synthetase is to join the t-shaped RNA with its amino acid. These aminoacylated tRNA's go on to the translation of an mRNA transcript, and are the fundamental elements that connect to the codon of the amino acid.[1] The necessity of the wobble base pair is illustrated through experimentation where the Guanine- Uracil pairing is changed to its natural Guanine- Cytosine pairing. Oligoboronucleotides were synthesized on a Gene Assembler Plus, and then spread across a DNA sequence known to code a tRNA for Alanine, 2D-NMR's are then run on the products of these new tRNA's and compared to the wobble tRNA's. The results indicate that with that wobble base pair changed, structure is also changed and an alpha helix can no longer be formed. The alpha helix was the recognizable structure for the aminoacyl tRNA synthetase and thus the synthetase does not connect the amino acid Alanine with the tRNA for Alanine. This wobble base pairing is essential for the use of the amino acid Alanine in E. Coli and its significance here would imply significance in many related species.[10] More information can be seen on aminoacyl tRNA synthetase and the genomes of E. Coli tRNA at External links 4 and 5, Information on Aminoacyl tRNA Synthetases and Genomic tRNA Database.

Mutation

A synonymous codon is one that despite a small mutation codes for the same amino acid. In the case of leucine, it has six codons that it will respectively identify as leucine, so if the original codon on the DNA sequence was C-U-A and there was a small mutation in the DNA sequence that led to a C-U-U codon, then leucine would still recognize that codon and translate the mRNA transcript. Codons in that sense are said to be synonymous.[11] In most cases, if the last nucleotide in the codon is changed it generally codes for the same amino acid. Occasionally, if one uses the last example of leucine one sees that if the C-U-A codon is changed to U-U-A it still codes for leucine. These would also be synonymous codons and show that even a base as important as the first can be changed, and because of Wobble the same amino acid anticodon will still be paired with the resulting codon.[12] Wobble cannot indirectly correct some mutations; many times a base pair is changed, and the codon codes for a different amino acid, creating mutations in the whole genome. If the mutation is for an amino acid with similar qualities, such as hydrophobic or polar tendencies, then there is a strong possibility that the resulting protein will resemble much of the same structure. But in cases like sickle-cell disease there is a single nucleotide polymorphism that results in an amino acid switch from glutamine to valine and that yields an entirely sickled red blood cell with limited capacity to carry oxygen.

Evolutionary importance

Codon bias is the tendency of codons to prefer one particular codon for an amino acid over all the others. So in the case of Leucine, it has 6 codons, 1 of those in the genome being respectively favored would be the definition of codon bias.[13] In many studies, most specifically known was the research efforts of a Bioinformatics and Proteomics Institute at the University of Toledo, it has been proven that a Guanine and Cytosine rich genome is preferred from an evolutionary standpoint. In this study they measured the Codon Adaptation Index, which is the geometric weight of the specific codon over the whole geometric weight of the genome, and found the CAI's for every codon among separate sets of organisms, namely humans, zebrafish, mice, and chickens. The results indicated that the codons with the highest CAI's represented the preferred codon, or the codon that receives the bias, and that these were codons rich in Guanine and Cytosine. The most apparent evidence of this was in Leucine which showed that the two codons which began with Uracil represented a much smaller percentage than the codons that began with Cytosine. This and many other examples set forth in the research demonstrated a tend toward Guanine and Cytosine in the genome and that these bases were evolutionarily superior and that held constant across all genomes.[14]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ These relationships can be further observed, as well as full codons and anticodons in the correct reading frame at: SBDR. "Genetic Code and Amino Acid Translation". Society for Biomedical Diabetes Research. Society for Biomedical Diabetes Research.

References

- 1 2 Campbell, Neil; Reece, Jane B. (2011). Biology (9th ed.). Boston: Benjamin Cummings. pp. 339–342. ISBN 0321558235.

- ↑ Kuchin, Sergei (19 May 2011). "Covering All the Bases in Genetics: Simple Shorthands and Diagrams for Teaching Base Pairing to Biology Undergraduates". Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education (American Society for Microbiology) 12 (1): 64–66. doi:10.1128/jmbe.v12i1.267. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

The correct name of the base in inosine (which is a nucleoside) is hypoxanthine, however, for consistency with the nucleic acid nomenclature, the shorthand [I] is more appropriate...

- ↑ Lowe, Todd; Chan, Patricia (18 April 2011). "Genomic tRNA Database". University of California, Santa Cruz. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Crick, F.H.C. (August 1966). "Codon—anticodon pairing: The wobble hypothesis" (PDF). Journal of Molecular Biology 19 (2): 548–555. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(66)80022-0. PMID 5969078. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Mathews, Christopher K.; Van Holde, K.E.; Appling, Dean; et al., eds. (2012). Biochemistry (4th ed.). Toronto: Prentice Hall. p. 1181. ISBN 978-0-13-800464-4.

- ↑ Voet, Donald; Voet, Judith (2011). Biochemistry (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1360–1361. ISBN 9780470570951.

- ↑ Varani, Gabriele; McClain, William H (July 2000). "The G·U wobble base pair". EMBO Reports 1 (1): 18–23. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvd001. PMC 1083677. PMID 11256617.

- ↑ Cox, Michael M.; Nelson, David L. (2013). "Protein Metabolism: Wobble Allows Some tRNA's to Recognize More than One Codon". Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (6th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. 1108–1110. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Murphy IV, Frank V; Ramakrishnan, V (21 November 2004). "Structure of a purine-purine wobble base pair in the decoding center of the ribosome". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 11 (12): 1251–1252. doi:10.1038/nsmb866. PMID 15558050. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Limmer, Stefan; Reif, Bernd; Ott, Gunther; Arnold, Lubos; Sprinzl, Mathias (19 February 1996). "NMR Evidence for Helix Geometry Modifications by a G-U Wobble Base Pair in the Acceptor Arm of E. Coli tRNA". FEBS.

- ↑ Miller, Kenneth; Levine, Joseph (1 January 2006). Prentice-Hall Biology (1st ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131662554.

- ↑ Hartwell, L.; Hood, L.; Goldberg, M.; Reynolds, A. (2011). Genetics: From Genes to Genomes (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 007352526X.

- ↑ Das, G.; Lyngdoh, D. (28 November 2007). "Can configuration of solitary wobble base pairs determine the specificity and degeneracy of the genetic code? Clues from molecular orbital modelling studies". Elsevier. Theochem (851).

- ↑ Nabiyouni, M.; Prakash, A.; Fedorov, A. (17 January 2013). "Vertebrate codon bias indicates a highly GC-rich ancestral genome". Elsevier (January): 1–7.

External links

- tRNA, the Adaptor Hypothesis and the Wobble Hypothesis

- Wobble base-pairing between codons and anticodons

- Genetic Code and Amino Acid Translation

- Information of Aminoacyl tRNA Synthetases

- Genomic tRNA Database