Within the Law (play)

| Within the Law | |

|---|---|

|

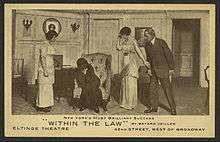

Advertising postcard for Within the Law | |

| Written by | Bayard Veiller |

| Date premiered | September 11, 1912[note 1] |

| Place premiered | Eltinge 42nd Street Theatre |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | Drama |

Within the Law is a play written by Bayard Veiller. It is the story of a woman who is wrongly accused of stealing and sent to prison. Upon her release, she sets up a gang that engages in shady activities that are just "within the law". After the police try to entrap her, she is mistakenly accused again, this time for murder, but she is vindicated when the real killer confesses.

Veiller used his experience as a crime reporter to develop the play, but he was initially unable to find a producer for it. He finally settled on selling the rights to the play, along with two others he had written, for a fixed fee. After an unsuccessful run in Chicago, it became a huge hit on Broadway in 1912–1913, running for 541 performances. It was subsequently performed by multiple road companies and adapted as a movie five times. Although it was one of the biggest hits of its era, Veiller got relatively little income from it due to his decision to sell it for a lump sum.

Plot

In the first act, word comes to the department store owned Edward Gilder that one of his former sales clerks, Mary Turner, has been convicted for stealing and given a three-year prison sentence. Gilder is pleased because he had asked the judge to make her an "example" to other employees. Turner asks to speak with Gilder before she goes to prison. While Gilder waits for her arrival, his store detective detains another woman, a customer, for stealing. This woman is the wife of a prominent banker, so rather than have her arrested, Gilder apologizes to her and lets her go. Turner arrives and tells Gilder she has been wrongly convicted. Although she says she never stole, she pleads with Gilder to increase the wages of his clerks, so no one who works there will be forced to steal. Gilder rejects her arguments, and she leaves for prison swearing revenge on him for his treatment of her.

Upon getting out of prison, she sets up a gang that engages in shady activities that are just within the boundaries of the law. She also marries the son of the owner of the store where she used to work. A member of the gang attempts to rob the home of Turner's new father-in-law at the urging of a police stooge attempting to entrap the gang. When the stooge reveals the plot, the gang member kills him, leaving Turner and her new husband at the scene to be found by the police. It seems that Turner may go to prison again, but she is saved when the guilty party confesses that she had no involvement in the crimes.[1][note 2]

History

Veiller began writing the play under the title The Miracle, which he later revised to The Case of Mary Turner and finally to Within the Law. In 1911 he took it to the Selwyn brothers (Archie and Edgar Selwyn), who brokered plays, to find a producer for it. Several prominent producers considered it, including David Belasco, George M. Cohan, Charles Frohman, Sam Harris, and Henry Wilson Savage. It was repeatedly rejected. The production duo of Louis Dreyfus and Herman Fellner took an option on the play, but they ran into financial difficulties and the option lapsed.[2][3][4]

Seeing few prospects for his work, Veiller offered to sell the rights to Within the Law and two other plays to the Selwyns for a flat fee of $3,750 (about $537,000 in 2013 dollars).[5] They eventually agreed. Soon after the play attracted the interest of producer William A. Brady. Brady asked George Broadhurst to make some script revisions, then staged a production in Chicago that opened in the spring of 1912. After a few weeks of unsuccessful results, Brady was disillusioned with the play and offered to sell the rights back to the Selwyns. The brothers bought it under the auspices of one of their businesses, the American Play Company. They were joined by several partners: Lee Shubert (who already had a share of the play as Brady's partner on the Chicago production), Albert H. Woods, and Crosby Gaige. Brady got $10,000 (about $1,337,000 in 2013 dollars),[5] enough to cover his costs for the Chicago production, but a tiny fraction of what the play would later earn.[2][3][4][6]

Woods brought the play to his newly built Eltinge 42nd Street Theatre in New York, where it was the venue's debut production. The show opened at the Eltinge in September 1912 and did not leave for over a year, becoming the biggest hit of the 1912-1913 Broadway season. After flubbing an important line on opening night, an actress bemoaned to Veiller that she had "ruined" his play. Reflecting on the production's critical and financial success in his autobiography, Veiller wished that more actresses had "ruined" his plays in this way.[7] Veiller earned no royalties, having sold his rights for a fixed fee. However, the Selwyns did not want to develop a reputation for taking advantage of authors, so they offered him a stipend of $100 per week for the Broadway run, and $50 per week for each road company (about $13,000 and $6,500 in 2013 dollars).[2][5] It was Veiller's first hit as a playwright.[4][8]

Productions

The play debuted at the Princess Theatre in Chicago on April 6, 1912. William A. Brady produced, and he had George Broadhurst make revisions to the script.[6] It closed on June 22, 1912.

The first and most successful Broadway production opened at the Eltinge 42nd Street Theatre on September 11, 1912. Holbrook Blinn directed the production and used Veiller's original script, without the changes made by Broadhurst. It was the first show ever staged at the Eltinge. It ran for 541 performances and did not close until December 1913.[6][9]

After the production closed at the Eltinge, multiple road companies were launched. Nine different companies toured North America, while another opened in the United Kingdom.[2]

A Broadway revival was staged in 1928, with Clifford Brook and Mabel Brownell directing. It opened at the Cosmopolitan Theatre on March 5, 1928, but closed after just 16 performances.[10]

Cast and characters

The play's protagonist and lead female role is Mary Turner, a shopgirl who becomes a criminal mastermind. Grace George initially accepted the part for the Chicago production, but changed her mind during rehearsals and decided she did not want to play the leader of a criminal gang. Emily Stevens took on the role instead.[2]

For the Broadway production, Jane Cowl was cast as Turner. Cowl specialized in portraying tearful women[11] and considered her skills well-adapted for the role.[12] Helen Ware filled in for Cowl when she took a brief vacation from the production's long run.[13]

Actor William B. Mack appeared in both the Chicago and Broadway productions, both times playing Joe Garson, the gang member responsible for the shooting.

The characters and cast from the Broadway production are given below:

| Character | Broadway first run cast[14] | Other notable performers[15] |

|---|---|---|

| Tom Tupper | Edward Bolton | |

| Richard Gilder | Orme Caldara | Charles Ray (1928 revival) |

| Dacey | John Camp | |

| Mary Turner | Jane Cowl; Helen Ware[13] | Emily Stevens (1912 Chicago production);[2] Violet Heming (1928 revival) |

| Thomas | Arthur Ebbetts | |

| Eddie Griggs | Kenneth Hill | Stanley Logan (1928 revival) |

| Dan | Frederick Howe | |

| George Demarest | Brandon Hurst | |

| Sarah | Georgia Lawrence | |

| Joe Garson | William B. Mack | Robert Warwick (1928 revival) |

| Edward Gilder | Dodson Mitchell | |

| Agnes Lynch | Florence Nash | Claudette Colbert (1928 revival) |

| Williams | Joseph Nickson | |

| William Irwin | William A. Norton | |

| "Chicago Red" | Arthur Paulding | |

| Smithson | S. V. Phillips | |

| Inspector Burke | Wilton Taylor | Frank Shannon (1928 revival) |

| Helen Morris | Catherine Tower | Peggy Allenby (1928 revival) |

| Fannie | Martha White | |

| Detective Sergeant Cassidy | John Willard | |

Reception

Reviews

The Broadway production received positive reviews. The reviewer for The New York Times called it "an exciting entertainment of the most vivid kind", praising the writing and the performances.[1] A review in Brooklyn Life called the story "extremely interesting and well told" and said there was "not a weak spot in the cast".[16]

Box office

Although it received positive reviews, the Chicago production was not a commercial success.

The New York Times review of the Broadway production predicted that the play was "sure of being extremely successful".[1] This prediction was accurate, as the show became a huge hit. The opening night had multiple curtain calls, and by the second night the theater was so packed that Veiller could not enter to watch the performance.[7] In 1914, Walter Reynolds called it "the greatest success of any modern melodrama produced in the metropolis",[6] and in 1915, theater journalist Rennold Wolf said it was possibly "the most profitable play of our generation".[3] By 1917, productions in the United States had taken in revenues of about $2.44 million ($221 million in 2013 dollars).[5][17]

Adaptations

Movies

The play was adapted as a movie five different times from 1916 to 1939:

- 1916 – a short Australian silent film directed by Monte Luke, starring Muriel Starr

- 1917 – an American silent film directed by William P.S. Earle, starring Alice Joyce

- 1923 – an American silent film directed by Frank Lloyd, starring Norma Talmadge

- 1930 – under the title Paid, an American film directed by Sam Wood, starring Joan Crawford

- 1939 – an American film directed by Gustav Machatý, starring Ruth Hussey

Other adaptations

In 1913, H.K. Fly published a novelization of the play, written by Marvin Dana.[18]

The play was adapted for television as an episode of Broadway Television Theatre that aired on June 2, 1952.[19]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 "Within the Law a Vivid Melodrama". The New York Times. September 12, 1912.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Luck of Bayard Veiller". The New York Times. December 10, 1916.

- 1 2 3 Wolf 1915, p. 147

- 1 2 3 Mantle 1938, p. 277

- 1 2 3 4 United States nominal Gross Domestic Product per capita figures follow the Measuring Worth series supplied in Williamson, Samuel H. (2015). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved April 15, 2015. These figures follow the figures as of 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Reynolds 1914, p. 450-451

- 1 2 Veiller 2010, pp. 202–203

- ↑ Kabatchnik 2009, pp. 124–125

- ↑ Henderson & Greene 2008, pp. 147–148

- ↑ Fisher & Londre 2008, p. 522

- ↑ Payne 1977, p. 130

- ↑ Cowl 1914, pp. 443–445

- 1 2 Kilgarif 1913, p. 206

- ↑ Unless otherwise cited, all cast info is from "Within the Law". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ↑ Cast info for 1928 revivial is from "Within the Law". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Plays and Players". Brooklyn Life 46 (1177). September 21, 1912. pp. 7, 32 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Silent Drama" (PDF). The Sunday Oregonian 36 (22). June 3, 1917. p. 4.5.

- ↑ "Within the Law ... From the play of Bayard Veiller". WorldCat. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ↑ Terrace 2013, p. 69

Works cited

- Cowl, Jane (March 1914). "The Sob Part". The Green Book Magazine 11 (3): 441–446.

- Fisher, James & Londre, Felicia Hardison (2008). The A to Z of American Theater: Modernism. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-6884-7.

- Henderson, Mary C. & Greene, Alexis (2008). The Story of 42nd Street: The Theaters, Shows, Characters, and Scandals of the World's Most Notorious Street. Back Stage Books. ISBN 9780823030729.

- Kabatchnik, Amnon (2009). Blood on the Stage, 1925-1950: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6963-9. OCLC 320351782.

- Kilgarif (August 1913). "The Stage: Miss Cowl's Ambition". Neale's Monthly 2 (2): 205–206.

- Mantle, Burns (1938). Contemporary American Playwrights. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company.

- Payne, Ben Iden (1977). A Life in a Wooden O: Memoirs of the Theatre. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02064-3. OCLC 2543000.

- Reynolds, Walter (March 1914). "Bayard Veiller: The Man Who Stuck". The Green Book Magazine 11 (3): 447–451.

- Veiller, Bayard (2010) [1941]. The Fun I've Had. Cornwall, New York: Cornwall Press. ISBN 978-1-4344-0659-0.

- Wolf, Rennold (January 1915). "Some New Chronicles of Broadway". The Green Book Magazine 13 (1): 145–151.

- Terrace, Vincent (2013). Television Specials: 5,336 Entertainment Programs, 1936–2012 (2nd ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7444-8. OCLC 844373010.

External links

- Within the Law at Theatricalia.com

- Within the Law at the Internet Broadway Database

- Text of the novelization at Project Gutenberg