Winter Olympic Games

| Olympic Games Jeux olympiques (French)[1] |

|---|

|

| Main topics |

| Games |

| Winter Olympic Games | |

|---|---|

| |

|

The Olympic flame in Sochi during the 2014 Winter Olympics. | |

| Games | |

| Sports (details) | |

The Winter Olympic Games (French: Jeux olympiques d'hiver)[nb 1] is a major international sporting event that occurs once every four years. Unlike the Summer Olympics, the Winter Olympics feature sports practiced on snow and ice. The first Winter Olympics, the 1924 Winter Olympics, was held in Chamonix, France. The original five sports (broken into nine disciplines) were bobsleigh, curling, ice hockey, Nordic skiing (consisting of the disciplines military patrol,[nb 2] cross-country skiing, Nordic combined, and ski jumping), and skating (consisting of the disciplines figure skating and speed skating).[nb 3] The Games were held every four years from 1924 until 1936, after which they were interrupted by World War II. The Olympics resumed in 1948 and was again held every four years. Until 1992, the Winter and Summer Olympic Games were held in the same years, but in accordance with a 1986 decision by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to place the Summer and Winter Games on separate four-year cycles in alternating even-numbered years, the next Winter Olympics after 1992 was in 1994.

The Winter Games have evolved since its inception. Sports and disciplines have been added and some of them, such as Alpine skiing, luge, short track speed skating, freestyle skiing, skeleton, and snowboarding, have earned a permanent spot on the Olympic program. Others (such as curling and bobsleigh) have been discontinued and later reintroduced, or have been permanently discontinued (such as military patrol, though the modern Winter Olympic sport of biathlon is descended from it).[nb 2] Still others, such as speed skiing, bandy and skijoring, were demonstration sports but never incorporated as Olympic sports. The rise of television as a global medium for communication enhanced the profile of the Games. It created an income stream, via the sale of broadcast rights and advertising, which has become lucrative for the IOC. This allowed outside interests, such as television companies and corporate sponsors, to exert influence. The IOC has had to address several criticisms, internal scandals, the use of performance-enhancing drugs by Winter Olympians, as well as a political boycott of the Winter Olympics. Nations have used the Winter Games to showcase the claimed superiority of their political systems.

The Winter Olympics has been hosted on three continents by eleven different countries. The United States has hosted the Games four times (1932, 1960, 1980, 2002); France has been the host three times (1924, 1968, 1992); Austria (1964, 1976), Canada (1988, 2010), Japan (1972, 1998), Italy (1956, 2006), Norway (1952, 1994), and Switzerland (1928, 1948) have hosted the Games twice. Germany (1936), Yugoslavia (1984), and Russia (2014) have hosted the Games once. The IOC has selected Pyeongchang, South Korea, to host the 2018 Winter Olympics and Beijing, China, to host the 2022 Winter Olympics. No country in the southern hemisphere has hosted or even been an applicant to host the Winter Olympics; the major challenge preventing one hosting the games is the dependence on winter weather, and the traditional February timing of the games falls in the middle of the southern hemisphere summer.

Twelve countries – Austria, Canada, Finland, France, Great Britain, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States – have sent athletes to every Winter Olympic Games. Six of those – Austria, Canada, Finland, Norway, Sweden and the United States – have earned medals at every Winter Olympic Games, and only one – the United States – has earned gold at each Games. Germany and Japan have been banned at times from competing in the Games.

Sports

Chapter 1, article 6 of the 2007 edition of the Olympic Charter defines winter sports as "sports which are practised on snow or ice."[6] Since 1992 a number of new sports have been added to the Olympic programme; which include short track speed skating, snowboarding, freestyle and moguls skiing. The addition of these events has broadened the appeal of the Winter Olympics beyond Europe and North America. While European powers such as Norway and Germany still dominate the traditional Winter Olympic sports, countries such as South Korea, Australia and Canada are finding success in the new sports. The results are more parity in the national medal tables, more interest in the Winter Olympics and higher global television ratings.[7]

Current sport disciplines

| Sport | Years | Events | Medal events contested in 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpine skiing | Since 1936 | 10 | Men's and women's downhill, super G, giant slalom, slalom, and combined.[8] |

| Biathlon | Since 1960Note 3 | 11 | Sprint (men: 10 km; women: 7.5 km), the individual (men: 20 km; women: 15 km), pursuit (men: 12.5 km; women: 10 km), relay (men: 4x7.5 km; women: 4x6 km; mixed: 2x7.5 km+2x6 km), and the mass start (men: 15 km; women: 12.5 km).[9] |

| Bobsleigh | 1924–1956 1964–present |

3 | Four-man race, two-man race and two-woman race.[10] |

| Cross-country skiing |

Since 1924 | 12 | Men's sprint, team sprint, 30 km pursuit, 15 km, 50 km and 4x10 km relay; women's sprint, team sprint, 15 km pursuit, 10 km, 30 km and 4x5 km relay.[11] |

| Curling | 1924 1998–present |

2 | Men's and women's tournaments.[12] |

| Figure skating | Since 1924Note 1 | 5 | Men's and women's singles; pairs; ice dancing and team event.[13] |

| Freestyle skiing | Since 1992 | 10 | Men's and women's moguls, aerials, ski cross, superpipe, and slopestyle.[14] |

| Ice hockey | Since 1924Note 2 | 2 | Men's and women's tournaments.[15] |

| Luge | Since 1964 | 4 | Men's and women's singles, men's doubles, team relay.[16] |

| Nordic combined | Since 1924 | 3 | Men's 10 km individual normal hill, 10 km individual large hill and team.[17] |

| Short track speed skating |

Since 1992 | 8 | Men's and women's 500 m, 1000 m, 1500 m; women's 3000 m relay; and men's 5000 m relay.[18] |

| Skeleton | 1928; 1948 Since 2002 |

2 | Men's and women's events.[19] |

| Ski jumping | Since 1924 | 4 | Men's individual large hill, team large hill.;[20] men's and women's individual normal hill. |

| Snowboarding | Since 1998 | 10 | Men's and women's parallel, giant slalom, half-pipe, snowboard cross, and slopestyle.[21] |

| Speed skating | Since 1924 | 12 | Men's and women's 500 m, 1000 m, 1500 m, 5000 m, and team pursuit; women's 3000 m; men's 10,000 m.[22] |

^ Note 1. Figure skating events were held at the 1908 and 1920 Summer Olympics.

^ Note 2. A men's ice hockey tournament was held at the 1920 Summer Olympics.

^ Note 3. The IOC's website now treats Men's Military Patrol at the 1924 games as an event within the sport of Biathlon.[nb 2]

Demonstration events

Demonstration sports have historically provided a venue for host countries to attract publicity to locally popular sports by having a competition without granting medals. Demonstration sports were discontinued after 1992.[23] Military patrol, a precursor to the biathlon, was a medal sport in 1924 and was demonstrated in 1928, 1936 and 1948, becoming an official sport in 1960.[24] The special figures figure skating event was only contested at the 1908 Summer Olympics.[25] Bandy (Russian hockey) is a sport popular in the Nordic countries and Russia. In the latter it's considered a national sport.[26] It was demonstrated at the Oslo Games.[27] Ice stock sport, a German variant of curling, was demonstrated in 1936 in Germany and 1964 in Austria.[28] The ski ballet event, later known as ski-acro, was demonstrated in 1988 and 1992.[29] Skijöring, skiing behind dogs, was a demonstration sport in St. Moritz in 1928.[27] A sled-dog race was held at Lake Placid in 1932.[27] Speed skiing was demonstrated in Albertville at the 1992 Winter Olympics.[30] Winter pentathlon, a variant of the modern pentathlon, was included as a demonstration event at the 1948 Games in Switzerland. It was composed of cross-country skiing, shooting, downhill skiing, fencing and horse riding.[9]

History

Early years

at the 1908 Olympics.

A predecessor, the Nordic Games, were organized by General Viktor Gustaf Balck in 1901 and were held again in 1903 and 1905 and then every fourth year thereafter until 1926.[31] Balck was a charter member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and a close friend of Olympic Games founder Pierre de Coubertin. He attempted to have winter sports, specifically figure skating, added to the Olympic program but was unsuccessful until the 1908 Summer Olympics in London, United Kingdom.[31] Four figure skating events were contested, at which Ulrich Salchow (10-time world champion) and Madge Syers won the individual titles.[32][33]

Three years later, Italian count Eugenio Brunetta d'Usseaux proposed that the IOC stage a week of winter sports included as part of the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden. The organizers opposed this idea because they desired to protect the integrity of the Nordic Games and were concerned about a lack of facilities for winter sports.[34][35][36] The idea was resurrected for the 1916 Games, which were to be held in Berlin, Germany. A winter sports week with speed skating, figure skating, ice hockey and Nordic skiing was planned, but the 1916 Olympics was cancelled after the outbreak of World War I.[35]

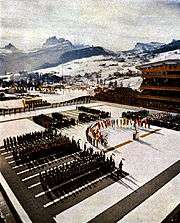

The first Olympics after the war, the 1920 Summer Olympics, were held in Antwerp, Belgium, and featured figure skating and an ice hockey tournament.[35] Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey were banned from competing in the Games. At the IOC Congress held the following year it was decided that the host nation of the 1924 Summer Olympics, France, would host a separate "International Winter Sports Week" under the patronage of the IOC. Chamonix was chosen to host this "week" (actually 11 days) of events. The Games proved to be a success when more than 250 athletes from 16 nations competed in 16 events.[37] Athletes from Finland and Norway won 28 medals, more than the rest of the participating nations combined.[38] Germany remained banned until 1925, and instead hosted a series of games called Deutsche Kampfspiele, starting with the Winter edition of 1922 (which predated the first Winter Olympics). In 1925 the IOC decided to create a separate Olympic Winter Games and the 1924 Games in Chamonix was retroactively designated as the first Winter Olympics.[35][37]

St. Moritz, Switzerland, was appointed by the IOC to host the second Olympic Winter Games in 1928.[39] Fluctuating weather conditions challenged the hosts. The opening ceremony was held in a blizzard while warm weather conditions plagued sporting events throughout the rest of the Games.[40] Because of the weather the 10,000 metre speed-skating event had to be abandoned and officially cancelled.[41] The weather was not the only noteworthy aspect of the 1928 Games: Sonja Henie of Norway made history when she won the figure skating competition at the age of 15. She became the youngest Olympic champion in history, a distinction she would hold for 74 years.[42]

The next Winter Olympics was the first to be hosted outside of Europe. Seventeen nations and 252 athletes participated.[43] This was less than in 1928 as the journey to Lake Placid, United States, was a long and expensive one for most competitors who had little money in the midst of the Great Depression. The athletes competed in fourteen events in four sports.[43] Virtually no snow fell for two months before the Games, and it was not until mid-January that there was enough snow to hold all the events.[44] Sonja Henie defended her Olympic title and Eddie Eagan, who had been an Olympic champion in boxing in 1920, won the gold in the men's bobsleigh event to become the first, and so far only, Olympian to have won gold medals in both the Summer and Winter Olympics.[43]

The German towns of Garmisch and Partenkirchen joined to organise the 1936 edition of the Winter Games, held on 6–16 February.[45] This would be the last time the Summer and Winter Olympics were held in the same country in the same year. Alpine skiing made its Olympic debut, but skiing teachers were barred from entering because they were considered to be professionals.[28] Because of this decision the Swiss and Austrian skiers refused to compete at the Games.[28]

World War II

World War II interrupted the celebrations of the Winter Olympics. The 1940 Games had been awarded to Sapporo, Japan, but the decision was rescinded in 1938 because of the Japanese invasion of China. The Games were moved to Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, but the German invasion of Poland in 1939 forced the complete cancellation of the 1940 Games.[46] Due to the ongoing war the 1944 Games, originally scheduled for Cortina D'Ampezzo, Italy, were cancelled.[47]

1948 to 1960

St. Moritz was selected to host the first post-war Games in 1948. Switzerland's neutrality had protected the town during World War II and most of the venues were in place from the 1928 Games, which made St. Moritz a logical choice. It became the first city to host a Winter Olympics twice.[48] Twenty-eight countries competed in Switzerland, but athletes from Germany and Japan were not invited.[49] Controversy erupted when two hockey teams from the United States arrived, both claiming to be the legitimate U.S. Olympic hockey representative. The Olympic flag presented at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp was stolen, as was its replacement. There was unprecedented parity at these Games, during which 10 countries won gold medals—more than any Games to that point.[50]

The Olympic Flame for the 1952 Games in Oslo, was lit in the fireplace by skiing pioneer Sondre Nordheim and the torch relay was conducted by 94 participants entirely on skis.[51][52] Bandy, a popular sport in the Nordic countries, was featured as a demonstration sport, though only Norway, Sweden and Finland fielded teams. Norwegian athletes won 17 medals, which outpaced all the other nations.[53] They were led by Hjalmar Andersen who won three gold medals in four events in the speed skating competition.[54]

After not being able to host the Games in 1944, Cortina d'Ampezzo was selected to organise the 1956 Winter Olympics. At the opening ceremonies the final torch bearer, Guido Caroli, entered the Olympic Stadium on ice skates. As he skated around the stadium his skate caught on a cable and he fell, nearly extinguishing the flame. He was able to recover and light the cauldron.[55] These were the first Winter Games to be televised and the first Olympics ever broadcast nationwide, though no television rights would be sold until the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome.[56] The Cortina Games were used to test the feasibility of televising large sporting events.[56] The Soviet Union made its Olympic debut and had an immediate impact, winning more medals than any other nation.[57] Chiharu Igaya won the first Winter Olympics medal for Japan and the continent of Asia, when he placed second in the slalom.[58]

The IOC awarded the 1960 Olympics to Squaw Valley, United States. Since the village was underdeveloped, there was a rush to construct infrastructure and sports facilities like an ice arena, speed-skating track, and a ski-jump hill.[59][60] The opening and closing ceremonies were produced by Walt Disney.[61] The Squaw Valley Olympics had a number of notable firsts: it was the first Olympics to have a dedicated athletes' village, it was the first to use a computer (courtesy of IBM) to tabulate results, and the first to feature female speed skating events. The bobsleigh events were absent for the only time, because the organising committee found it too expensive to build the bobsleigh run.[61]

1964 to 1980

The Austrian city of Innsbruck was the host in 1964. Although Innsbruck was a traditional winter sports resort, warm weather caused a lack of snow during the Games and the Austrian army was asked to transport snow and ice to the sport venues.[61] Soviet speed-skater Lidia Skoblikova made history by sweeping all four speed-skating events. Her career total of six gold medals set a record for Winter Olympics athletes.[61] Luge was first contested in 1964, although the sport received bad publicity when a competitor was killed in a pre-Olympic training run.[62][63]

Held in the French town of Grenoble, the 1968 Winter Olympics were the first Olympic Games to be broadcast in colour. There were 37 nations and 1,158 athletes competing in 35 events.[64] Frenchman Jean-Claude Killy became only the second person to win all the men's alpine skiing events. The organising committee sold television rights for $2 million, which was more than double the price of the broadcast rights for the Innsbruck Games.[65] Venues were spread over long distances requiring three athletes' villages. The organisers claimed this was required to accommodate technological advances. Critics disputed this, alleging that the layout was necessary to provide the best possible venues for television broadcasts at the expense of the athletes.[65]

The 1972 Winter Games, held in Sapporo, Japan, were the first to be hosted outside North America or Europe. The issue of professionalism became contentious during the Sapporo Games. Three days before the Games IOC president Avery Brundage threatened to bar a number of alpine skiers from competing because they participated in a ski camp at Mammoth Mountain in the United States. Brundage reasoned that the skiers had financially benefited from their status as athletes and were therefore no longer amateurs.[66] Eventually only Austrian Karl Schranz, who earned more than all the other skiers, was not allowed to compete.[67] Canada did not send teams to the 1972 or 1976 ice hockey tournaments in protest of their inability to use players from professional leagues.[68] Francisco Fernández Ochoa became the first (and only) Spaniard to win a Winter Olympic gold medal; he triumphed in the slalom.[69]

The 1976 Winter Olympics had been awarded in 1970 to Denver, United States, but in November 1972 the voters of the state of Colorado voted against public funding of the games by a 3 to 2 margin.[70][71] The IOC turned to offer the Games to Vancouver-Garibaldi, British Columbia, which had been a candidate for the 1976 Games. However, a change in provincial government brought in an administration which did not support the Olympic bid, so the offer was rejected. Salt Lake City, a candidate for the 1972 Games, offered itself, but the IOC opted to ask Innsbruck, which had maintained most of the infrastructure from the 1964 Games. With half the time to prepare for the Games as intended, Innsbruck accepted the invitation to replace Denver in February 1973.[72] Two Olympic flames were lit because it was the second time the Austrian town had hosted the Games.[72] The 1976 Games featured the first combination bobsleigh and luge track, in neighbouring Igls.[69] The Soviet Union won its fourth consecutive ice hockey gold medal.[72]

In 1980 the Olympics returned to Lake Placid, which had hosted the 1932 Games. The first boycott of a Winter Olympics occurred in 1980 when Taiwan refused to participate after an edict by the IOC mandated that they change their name and national anthem.[73] The IOC was attempting to accommodate China, who wished to compete using the same name and anthem that had been used by Taiwan.[73] American speed-skater Eric Heiden set either an Olympic or world record in each of the five events he competed in.[74] Hanni Wenzel won both the slalom and giant slalom and her country, Liechtenstein, became the smallest nation to produce an Olympic gold medallist.[75] In the "Miracle on Ice" the American hockey team beat the favoured Soviets, and then went on to win the gold medal.[76][nb 4]

1984 to 1998

Sapporo, Japan, and Gothenburg, Sweden, were front-runners to host the 1984 Winter Olympics. It was therefore a surprise when Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, was selected as host.[79] The Games were well-organised and displayed no indication of the war that would engulf the country eight years later.[80] A total of 49 nations and 1,272 athletes participated in 39 events. Host nation Yugoslavia won its first Olympic medal when alpine skier Jure Franko won a silver in the giant slalom. Another sporting highlight was the free dance performance of British ice dancers Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean. Their performance to Ravel's Boléro earned the pair the gold medal after achieving unanimous perfect scores for artistic impression.[80]

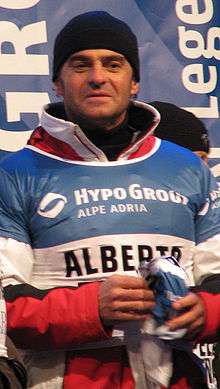

In 1988, the Canadian city of Calgary hosted the first Winter Olympics to span 16 days.[81] New events were added in ski-jumping and speed skating; while future Olympic sports curling, short track speed skating and freestyle skiing made their appearance as demonstration sports. For the first time the speed skating events were held indoors, on the Olympic Oval. Dutch skater Yvonne van Gennip won three gold medals and set two world records, beating skaters from the favoured East German team in every race.[82] Her medal total was equalled by Finnish ski jumper Matti Nykänen, who won all three events in his sport. Alberto Tomba, an Italian skier, made his Olympic debut by winning both the giant slalom and slalom. East German Christa Rothenburger won the women's 1,000 metre speed skating event. Seven months later she would earn a silver in track cycling at the Summer Games in Seoul, to become the only athlete to win medals in both a Summer and Winter Olympics in the same year.[81]

The 1992 Games were the last to be held in the same year as the Summer Games.[83] They were hosted in the French Savoie region in the city of Albertville, though only 18 events were held in the city. The rest of the events were spread out over the Savoie.[83] Political changes of the time were reflected in the Olympic teams appearing in France: this was the first Games to be held after the fall of Communism and the dismantling of the Berlin Wall, and Germany competed as a single nation for the first time since the 1964 Games; former Yugoslavian republics Croatia and Slovenia made their debuts as independent nations; most of the former Soviet republics still competed as a single team known as the Unified Team, but the Baltic States made independent appearances for the first time since before World War II.[84] At 16 years old, Finnish ski jumper Toni Nieminen made history by becoming the youngest male Winter Olympic champion.[85] New Zealand skier Annelise Coberger became the first Winter Olympic medallist from the southern hemisphere when she won a silver medal in the women's slalom.

In 1986 the IOC had voted to separate the Summer and Winter Games and place them in alternating even-numbered years. This change became effective for the 1994 Games, held in Lillehammer, Norway, which became the first Winter Olympics to be held separate from the Summer Games.[86] After the division of Czechoslovakia in 1993 the Czech Republic and Slovakia made their Olympic debuts.[87] The women's figure skating competition garnered media attention when American skater Nancy Kerrigan was injured on 6 January 1994, in an assault planned by the ex-husband of opponent Tonya Harding.[88] Both skaters competed in the Games, but the gold medal was won by Oksana Baiul. She became Ukraine's first Olympic champion.[89][90] Johann Olav Koss of Norway won three gold medals, coming first in all of the distance speed skating events.[91]

The 1998 Winter Olympics were held in the Japanese city of Nagano and were the first Games to host more than 2,000 athletes.[92] The men's ice hockey tournament was opened to professionals for the first time. Canada and the United States, with their many NHL players, were favoured to win the tournament.[92] Neither won any hockey medals however, as the Czech Republic prevailed.[92] Women's ice hockey made its debut and the United States won the gold medal.[93] Bjørn Dæhlie of Norway won three gold medals in Nordic skiing. He became the most decorated Winter Olympic athlete with eight gold medals and twelve medals overall.[92][94] Austrian Hermann Maier survived a crash during the downhill competition and returned to win gold in the super-g and the giant slalom.[92] A wave of new world records were set in speed skating because of the introduction of the clap skate.[95]

2002 to 2010

The 2002 Winter Olympics were held in Salt Lake City, United States, hosting 77 nations and 2,399 athletes in 78 events in 7 sports.[96] These games were the first to take place since 11 September 2001, which meant a higher degree of security to avoid a terrorist attack. The opening ceremonies of the games saw signs of the aftermath of the events of that day, including the flag that flew at Ground Zero, NYPD officer Daniel Rodríguez singing "God Bless America", and honor guards of NYPD and FDNY members.

German Georg Hackl won a silver in the singles luge, becoming the first athlete in Olympic history to win medals in the same individual event in five consecutive Olympics.[96] Canada achieved an unprecedented double by winning both the men's and women's ice hockey gold medals.[96] Canada became embroiled with Russia in a controversy that involved the judging of the pairs figure skating competition. The Russian pair of Yelena Berezhnaya and Anton Sikharulidze competed against the Canadian pair of Jamie Salé and David Pelletier for the gold medal. The Canadians appeared to have skated well enough to win the competition, yet the Russians were awarded the gold. The judging broke along Cold War lines with judges from former Communist countries favouring the Russian pair and judges from Western nations voting for the Canadians. The only exception was the French judge, Marie-Reine Le Gougne, who awarded the gold to the Russians. An investigation revealed that she had been pressured to give the gold to the Russian pair regardless of how they skated; in return the Russian judge would look favourably on the French entrants in the ice dancing competition.[97] The IOC decided to award both pairs the gold medal in a second medal ceremony held later in the Games.[98] Australian Steven Bradbury became the first gold medallist from the southern hemisphere when he won the 1,000 metre short-track speed skating event.[99]

The Italian city of Turin hosted the 2006 Winter Olympics. It was the second time that Italy had hosted the Winter Olympic Games. South Korean athletes won 10 medals, including 6 gold in the short-track speed skating events. Sun-Yu Jin won three gold medals while her teammate Hyun-Soo Ahn won three gold medals and a bronze.[100] In the women's Cross-Country team pursuit Canadian Sara Renner broke one of her poles and, when he saw her dilemma, Norwegian coach Bjørnar Håkensmoen decided to lend her a pole. In so doing she was able to help her team win a silver medal in the event at the expense of the Norwegian team, who finished fourth.[100][101] Claudia Pechstein of Germany became the first speed skater to earn nine career medals.[100] In February 2009 Pechstein tested positive for "blood manipulation" and received a two-year suspension, which she appealed. The Court of Arbitration for Sport upheld her suspension but a Swiss court ruled that she could compete for a spot on the 2010 German Olympic team.[102] This ruling was brought to the Swiss Federal Tribunal, which overturned the lower court's ruling and precluded her from competing in Vancouver.[103]

In 2003 the IOC awarded the 2010 Winter Olympics to Vancouver, thus allowing Canada to host its second Winter Olympics. With a population of more than 2.5 million people Vancouver is the largest metropolitan area to ever host a Winter Olympic Games.[104] Over 2,500 athletes from 82 countries participated in 86 events.[105] The death of Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili in a training run on the day of the opening ceremonies resulted in the Whistler Sliding Centre changing the track layout on safety grounds.[106] Norwegian cross-country skier Marit Bjørgen won five medals in the six cross-country events on the women's programme. She finished the Olympics with three golds, a silver and a bronze.[107] The Vancouver Games were notable for the poor performance of the Russian athletes. From their first Winter Olympics in 1956 to the 2006 games, a Soviet or Russian delegation had never been outside the top five medal-winning nations. In 2010 they finished sixth in total medals and eleventh in gold medals. President Dmitry Medvedev called for the resignation of top sports officials immediately after the Games.[108] The success of Asian countries stood in stark contrast to the under-performing Russian team, with Vancouver marking a high point for medals won by Asian countries. In 1992 the Asian countries had won fifteen medals, three of which were gold. In Vancouver the total number of medals won by athletes from Asia had increased to thirty-one, with eleven of them being gold. The rise of Asian nations in Winter Olympics sports is due in part to the growth of winter sports programmes and the interest in winter sports in nations such as South Korea, Japan and China.[109][110]

2014

Sochi, Russia, was selected as the host city of the 2014 Winter Olympics over Salzburg, Austria, and Pyeongchang, South Korea. This was the first time since the breakup of the Soviet Union that Russia hosted a Winter Olympics.[111] Over 2800 athletes from 88 countries participated in 98 events. The Olympic Village and Olympic Stadium were located on the Black Sea coast. All of the mountain venues were 50 kilometres (31 mi) away in the alpine region known as Krasnaya Polyana.[111]

The 2014 Winter Olympics, officially the XXII Olympic Winter Games, or the 22nd Winter Olympics, took place from 7 to 23 February 2014.[112]

Future

On 6 July 2011, the IOC selected the city of Pyeongchang, South Korea to host the 2018 Winter Olympics.[113]

The host city for the XXIV Olympic Winter Games, also known as the 2022 Winter Olympics, is Beijing, elected on 31 July 2015, at the 128th IOC Session in Kuala Lumpur. Beijing will be the first city to host both the summer and winter olympics.

Controversy

The process for awarding host city honours came under intense scrutiny after Salt Lake City had been awarded the right to host the 2002 Games.[114] Soon after the host city had been announced it was discovered that the organisers had engaged in an elaborate bribery scheme to curry favour with IOC officials.[114] Gifts and other financial considerations were given to those who would evaluate and vote on Salt Lake City's bid. These gifts included medical treatment for relatives, a college scholarship for one member's son and a land deal in Utah. Even IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch received two rifles valued at $2,000. Samaranch defended the gift as inconsequential since, as president, he was a non-voting member.[115] The subsequent investigation uncovered inconsistencies in the bids for every Games (both summer and winter) since 1988.[116] For example, the gifts received by IOC members from the Japanese Organising Committee for Nagano's bid for the 1998 Winter Olympics were described by the investigation committee as "astronomical".[117] Although nothing strictly illegal had been done, the IOC feared that corporate sponsors would lose faith in the integrity of the process and that the Olympic brand would be tarnished to such an extent that advertisers would begin to pull their support.[118] The investigation resulted in the expulsion of 10 IOC members and the sanctioning of another 10. New terms and age limits were established for IOC membership, and 15 former Olympic athletes were added to the committee. Stricter rules for future bids were imposed, with ceilings imposed on the value of gifts IOC members could accept from bid cities.[119][120][121]

Host city legacy

According to the IOC, the host city is responsible for, "...establishing functions and services for all aspects of the Games, such as sports planning, venues, finance, technology, accommodation, catering, media services etc., as well as operations during the Games."[122] Due to the cost of hosting an Olympic Games, most host cities never realise a profit on their investment.[123] For example, the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, Japan, cost $12.5 billion. By comparison the Torino Games of 2006 cost $3.6 billion to host.[124] The organisers claimed that the cost of extending the bullet train service from Tokyo to Nagano was responsible for the large price tag.[124] The organising committee hoped that the exposure of the Olympic Games, and the expedited access to Nagano from Tokyo, would be a boon to the local economy for years afterward. Nagano's economy did experience a two-year post-Olympic spurt, but the long-term effects have not materialised as planned.[124] The possibility of heavy debt, coupled with unused sports venues and infrastructure that saddle the local community with upkeep costs and no practical post-Olympic value, is a deterrent to prospective host cities.[125]

To mitigate these concerns the IOC has enacted several initiatives. First it has agreed to fund part of the host city's budget for staging the Games.[126] Secondly, the IOC limits the qualifying host countries to those that have the resources and infrastructure to successfully host an Olympic Games without negatively impacting the region or nation. This eliminates a large portion of the developing world.[127] Finally, cities bidding to host the Games are required to add a "legacy plan" to their proposal. This requires prospective host cities and the IOC, to plan with a view to the long-term economic and environmental impact that hosting the Olympics will have on the region.[128]

Doping

In 1967 the IOC began enacting drug testing protocols. They started by randomly testing athletes at the 1968 Winter Olympics.[129] The first Winter Games athlete to test positive for a banned substance was Alois Schloder, a West German hockey player,[130] but his team was still allowed to compete.[131] During the 1970s testing outside of competition was escalated because it was found to deter athletes from using performance-enhancing drugs.[132] The problem with testing during this time was a lack of standardisation of the test procedures, which undermined the credibility of the tests. It was not until the late 1980s that international sporting federations began to coordinate efforts to standardise the drug-testing protocols.[133] The IOC took the lead in the fight against steroids when it established the independent World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) in November 1999.[134][135]

The 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin became notable for a scandal involving the emerging trend of blood doping, the use of blood transfusions or synthetic hormones such as Erythropoietin (EPO) to improve oxygen flow and thus reduce fatigue.[136] The Italian police conducted a raid on the Austrian cross-country ski team's residence during the Games where they seized blood-doping specimens and equipment.[137] This event followed the pre-Olympics suspension of 12 cross-country skiers who tested positive for unusually high levels of hemoglobin, which is evidence of blood doping.[136]

Commercialisation

Avery Brundage, as president of the IOC from 1952 to 1972, rejected all attempts to link the Olympics with commercial interests as he felt that the Olympic movement should be completely separate from financial influence.[138] The 1960 Winter Olympics marked the beginning of corporate sponsorship of the Games.[138] Despite Brundage's strenuous resistance the commercialisation of the Games continued during the 1960s, and revenue generated by corporate sponsorship swelled the IOC's coffers.[139] By the Grenoble Games, Brundage had become so concerned about the direction of the Winter Olympic Games towards commercialisation that, if it could not be corrected, he felt the Winter Olympics should be abolished.[140] Brundage's resistance to this revenue stream meant that the IOC was unable to gain a share of the financial windfall that was coming to host cities, and had no control over the structuring of sponsorship deals. When Brundage retired the IOC had $2 million in assets; eight years later its accounts had swelled to $45 million. This was due to a shift in ideology among IOC members, towards expansion of the Games through corporate sponsorship and the sale of television rights.[138]

Brundage's concerns proved prophetic. The IOC has charged more for television broadcast rights at each successive Games.[141] At the 1998 Nagano Games American broadcaster CBS paid $375 million, whereas the 2006 Turin Games cost NBC $613 million to broadcast.[142] The more television companies have paid to televise the Games, the greater their persuasive power has been with the IOC.[141][143] For example, the television lobby has influenced the Olympic programme by dictating when event finals are held, so that they appear in prime time for television audiences. They have pressured the IOC to include new events, such as snowboarding, that appeal to broader television audiences. This has been done to boost ratings, which were slowly declining until the 2010 Games.[144][145]

In 1986 the IOC decided to stagger the Summer and Winter Games. Instead of holding both in the same calendar year the committee decided to alternate them every two years, although both Games would still be held on four-year cycles.[146] It was decided that 1992 would be the last year to have both a Winter and Summer Olympic Games.[86] There were two underlying reasons for this change: first was the television lobby's desire to maximise advertising revenue as it was difficult to sell advertising time for two Games in the same year;[146] second was the IOC's desire to gain more control over the revenue generated by the Games. It was decided that staggering the Games would make it easier for corporations to sponsor individual Olympic Games, which would maximise revenue potential. The IOC sought to directly negotiate sponsorship contracts so that they had more control over the Olympic "brand".[147] The first Winter Olympics to be hosted in this new format were the 1994 Games in Lillehammer.[83]

Politics

Cold War

_1968%2C_MiNr_1339.jpg)

The Winter Olympics have been an ideological front in the Cold War since the Soviet Union first participated at the 1956 Winter Games. It did not take long for the Cold War combatants to discover what a powerful propaganda tool the Olympic Games could be. Soviet and American politicians used the Olympics as an opportunity to demonstrate the superiority of their respective political systems.[148] The successful Soviet athlete was feted and honoured. Irina Rodnina, three-time Olympic gold medallist in figure skating, was awarded the Order of Lenin after her victory at the 1976 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck.[149] Soviet athletes who won gold medals could expect to receive between $4,000 and $8,000 depending on the prestige of the sport. A world record was worth an additional $1,500.[150] In 1978 the United States Congress responded to these measures by passing legislation that reorganised the United States Olympic Committee. It also approved financial rewards to medal-winning athletes.[151]

The Cold War created tensions amongst countries allied to the two superpowers. The strained relationship between East and West Germany created a difficult political situation for the IOC. Because of its role in World War II, Germany was not allowed to compete at the 1948 Winter Olympics.[49] In 1950 the IOC recognised the West German Olympic Committee, and invited East and West Germany to compete as a unified team at the 1952 Winter Games.[152] East Germany declined the invitation and instead sought international legitimacy separate from West Germany.[153] In 1955 the Soviet Union recognised East Germany as a sovereign state, thereby giving more credibility to East Germany's campaign to become an independent participant at the Olympics. The IOC agreed to provisionally accept the East German National Olympic Committee with the condition that East and West Germans compete on one team.[154] The situation became tenuous when the Berlin Wall was constructed in 1962 and western nations began refusing visas to East German athletes.[155] The uneasy compromise of a unified team held until the 1968 Grenoble Games when the IOC officially split the teams and threatened to reject the host-city bids of any country that refused entry visas to East German athletes.[156]

Boycott

The Winter Games have had only one national team boycott when Taiwan decided not to participate in the 1980 Winter Olympics held in Lake Placid. Prior to the Games the IOC agreed to allow China to compete in the Olympics for the first time since 1952. China was given permission to compete as the "People's Republic of China" (PRC) and to use the PRC flag and anthem. Until 1980 the island of Taiwan had been competing under the name "Republic of China" (ROC) and had been using the ROC flag and anthem.[73] The IOC attempted to have the countries compete together but when this proved to be unacceptable the IOC demanded that Taiwan cease to call itself the "Republic of China".[157][158] The IOC renamed the island "Chinese Taipei" and demanded that it adopt a different flag and national anthem, stipulations that Taiwan would not agree to. Despite numerous appeals and court hearings the IOC's decision stood. When the Taiwanese athletes arrived at the Olympic village with their Republic of China identification cards they were not admitted. They subsequently left the Olympics in protest, just before the opening ceremonies.[73] Taiwan returned to Olympic competition at the 1984 Winter Games in Sarajevo as Chinese Taipei. The country agreed to compete under a flag bearing the emblem of their National Olympic Committee and to play the anthem of their National Olympic Committee should one of their athletes win a gold medal. The agreement remains in place to this day.[159]

All-time medal table

With reference to the top ten nations and according to official data of the International Olympic Committee.

| No. | Nation | Games | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | 118 | 111 | 100 | 329 | |

| 2 | 22 | 96 | 102 | 84 | 282 | |

| 3 | 11 | 78 | 78 | 53 | 209 | |

| 4 | 9 | 78 | 57 | 59 | 194 | |

| 5 | 22 | 62 | 56 | 52 | 170 | |

| 6 | 22 | 59 | 78 | 81 | 218 | |

| 7 | 22 | 50 | 40 | 54 | 144 | |

| 8 | 22 | 50 | 40 | 48 | 138 | |

| 9 | 6 | 49 | 40 | 35 | 124 | |

| 10 | 22 | 42 | 62 | 57 | 161 | |

| 11 | 6 | 39 | 36 | 35 | 110 | |

| 12 | 22 | 37 | 34 | 43 | 114 |

List of Winter Olympic Games

| Games | Year | Host | Opened by | Dates | Nations | Competitors | Sports | Disci- plines |

Events | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Men | Women | ||||||||||

| I | 1924 | |

Undersecretary Gaston Vidal | 25 January – 5 February | 16 | 258 | 247 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 16 | |

| II | 1928 | |

President Edmund Schulthess | 11–19 February | 25 | 464 | 438 | 26 | 4 | 8 | 14 | |

| III | 1932 | |

Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt | 4–15 February | 17 | 252 | 231 | 21 | 4 | 7 | 14 | |

| IV | 1936 | |

Chancellor Adolf Hitler | 6–16 February | 28 | 646 | 566 | 80 | 4 | 8 | 17 | |

| 1940 | Awarded to Sapporo, Japan; cancelled because of World War II | |||||||||||

| 1944 | Awarded to Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy; cancelled because of World War II | |||||||||||

| V | 1948 | |

President Enrico Celio | 30 January – 8 February | 28 | 669 | 592 | 77 | 4 | 9 | 22 | |

| VI | 1952 | |

Princess Ragnhild | 14–25 February | 30 | 694 | 585 | 109 | 4 | 8 | 22 | |

| VII | 1956 | |

President Giovanni Gronchi | 26 January – 5 February | 32 | 821 | 687 | 134 | 4 | 8 | 24 | |

| VIII | 1960 | |

Vice President Richard Nixon | 18–28 February | 30 | 665 | 521 | 144 | 4 | 8 | 27 | |

| IX | 1964 | |

President Adolf Schärf | 29 January – 9 February | 36 | 1091 | 892 | 199 | 6 | 10 | 34 | |

| X | 1968 | |

President Charles de Gaulle | 6–18 February | 37 | 1158 | 947 | 211 | 6 | 10 | 35 | |

| XI | 1972 | |

Emperor Hirohito | 3–13 February | 35 | 1006 | 801 | 205 | 6 | 10 | 35 | |

| XII | 1976 | |

President Rudolf Kirchschläger | 4–15 February | 37 | 1123 | 892 | 231 | 6 | 10 | 37 | |

| XIII | 1980 | |

Vice President Walter Mondale | 13–24 February | 37 | 1072 | 840 | 232 | 6 | 10 | 38 | |

| XIV | 1984 | |

President Mika Špiljak | 8–19 February | 49 | 1272 | 998 | 274 | 6 | 10 | 39 | |

| XV | 1988 | |

Governor General Jeanne Sauvé | 13–28 February | 57 | 1423 | 1122 | 301 | 6 | 10 | 46 | |

| XVI | 1992 | |

President François Mitterrand | 8–23 February | 64 | 1801 | 1313 | 488 | 6 | 12 | 57 | |

| XVII | 1994 | |

King Harald V | 12–27 February | 67 | 1737 | 1215 | 522 | 6 | 12 | 61 | |

| XVIII | 1998 | |

Emperor Akihito | 7–22 February | 72 | 2176 | 1389 | 787 | 7 | 14 | 68 | |

| XIX | 2002 | |

President George W. Bush | 8–24 February | 78[160] | 2399 | 1513 | 886 | 7 | 15 | 78 | |

| XX | 2006 | |

President Carlo Azeglio Ciampi | 10–26 February | 80 | 2508 | 1548 | 960 | 7 | 15 | 84 | |

| XXI | 2010 | |

Governor General Michaëlle Jean | 12–28 February | 82 | 2566 | 1522 | 1044 | 7 | 15 | 86 | |

| XXII | 2014 | |

President Vladimir Putin | 7–23 February | 88 | 2873 | 1714 | 1159 | 7 | 15 | 98 | |

| XXIII | 2018 | |

9–25 February | Future event | 7 | 15 | 102 | |||||

| XXIV | 2022 | |

4–20 February | Future event | 7 | 15 | 102 | |||||

| XXV | 2026 | Selection: 2019 | Future event | |||||||||

Unlike the Summer Olympics, the cancelled 1940 Winter Olympics and 1944 Winter Olympics are not included in the official Roman numeral counts for the Winter Games. While the official titles of the Summer Games count Olympiads, the titles of the Winter Games only count the Games themselves.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "French and English are the official languages for the Olympic Games.", .(..)

- 1 2 3 The official website of the Olympic Movement now treats Men's Military Patrol at the 1924 games as an event within the sport of Biathlon.[2][3] However, the 1924 Official Report treats it as an event and discipline within what was then called Skiing and is now called Nordic Skiing.[4][5]

- ↑ At the closing of the 1924 games a prize was also awarded for 'alpinisme' (mountaineering), a sport that did not lend itself very well for tournaments: Pierre de Coubertin presented a prize for 'alpinisme' to Charles Granville Bruce, the leader of the expedition that tried to climb Mount Everest in 1922.

- ↑ They beat the Soviets as part of a medal round that also included Finland and Sweden, so they didn't actually win the gold medal until they beat Finland a few days later.[77][78]

References

- ↑ "Jeux Olympiques - Sports, Athlètes, Médailles, Rio 2016". olympic.org.

- ↑ "Biathlon Results - Chamonix 1924". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ "Olympic Games Medals, Chamonix 1924". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Official Report (1924), p 646: Le Programme ... II. — Epreuves par équipes - 12. Ski : Course militaire (20 à 30 kilomètres, avec tir). (The Programme ... II. — Team events - 12. Skiing : Military Race (20 to 30 kilometres, with shooting)).

- ↑ Official Report (1924), p 664: CONCOURS DE SKI - Jurys - COURSE MILITAIRE. (Skiing Competitions - Juries - Military Race)

- ↑ "Olympic Charter" (PDF) (Press release). International Olympic Committee. 7 July 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ↑ Sappenfield, Mark (25 February 2010). "USA, Canada ride new sports to top of Winter Olympics medal count". The Christian Science Monitor (CSMonitor.com). Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ↑ "Alpine Skiing". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- 1 2 "Biathlon". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Bobsleigh". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Cross Country Skiing". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Curling". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Figure Skating". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Freestyle skiing". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Ice Hockey". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Luge". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Nordic Combined". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Short Track Speed Sskating". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Skeleton". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Ski Jumping". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Snowboard". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Speed Skating". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Olympic Sports". Inside The Games. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ "Biathlon history". USBiathlon.org. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ↑ "Figure Skating at the 1908 London Summer Games". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ↑ "Russian bandy players blessed for victory at world championship in Kazan". Tatar-Inform. 21 January 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- 1 2 3 Arnold, Eric (28 January 2010). "Strangest Olympics Sports In History". Forbes (Forbes.com). Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Garmisch-Partenkirchen Olympics". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ "Freestyle Skiing History". The National Post (Canadian Broadcasting Company). 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ Janofsky, Michael (18 December 1991). "Hitting the slopes in the fast lane". The New York Times (NYTimes.com). Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- 1 2 Edgeworth, Ron (May 1994). "The Nordic Games and the Origins of the Winter Olympic Games" (PDF). International Society of Olympic Historians Journal (LA84 Foundation) 2 (2). Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ↑ "1908 Figure Skating Results". CNNSI.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2001. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ↑ "Figure Skating History". CNNSI.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2004. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ↑ Judd (2008), p. 21

- 1 2 3 4 "1924 Chamonix, France". CBC Sports (CBC.ca). 18 December 2009. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 283

- 1 2 "Chamonix 1924". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ "1924 Chamonix Winter Games". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), pp. 289–290

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 290

- ↑ "1928 Sankt Moritz Winter Games". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ↑ "St. Moritz 1928". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Lake Placid 1932". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 298

- ↑ Seligmann, Davison, and McDonald (2004), p. 119

- ↑ Lund, Mortund (December 2001). "The First Four Olympics". Skiing Heritage Journal (International Skiing History Association): 21. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Mallon and Buchanon (2006), p. xxxii

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 248

- 1 2 "St. Moritz 1948". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), pp. 250–251

- ↑ "Oslo 1952". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 255

- ↑ "1952 Oslo Winter Games". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ "Speed Skating at the 1952 Oslo Winter Games". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ "1956 Cortina d'Ampezzo Winter Games". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- 1 2 Guttman (1986), p. 135

- ↑ "Cortina d'Ampezzo 1956". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ↑ "Chiharu Igaya". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ↑ Judd (2008), pp. 27–28

- ↑ Shipler, Gary (February 1960). "Backstage at Winter Olympics". Popular Science (Bonnier Corporation): 138. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Judd (2008), p. 28

- ↑ "Innsbruck 1964". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Judd (2008), p. 29

- ↑ "Grenoble 1968". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- 1 2 Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 277

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 286

- ↑ Fry (2006), pp. 153–154

- ↑ Podnieks, Andrew; Szemberg, Szymon (2008). "Story #17–Protesting amateur rules, Canada leaves international hockey". International Ice Hockey Federation. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- 1 2 "Factsheet Olympic Winter Games" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. January 2008. p. 5. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ↑ "Colorado only state ever to turn down Olympics". Denver.rockymountainnews.com. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ Fry (2006), p. 157

- 1 2 3 "Innsbruck 1976". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Findling and Pelle (1996), p. 299

- ↑ Judd (2008), pp. 135–136

- ↑ "Lake Placid 1980". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ Huber, Jim (22 February 2000). "A Golden Moment". CNNSI.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "LAKE PLACID 1980 - USA ice hockey team". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "LAKE PLACID 1980 - Photo - Finland v USA". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "1984 Sarajevo". CNNSI.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2004. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- 1 2 "Sarajevo 1984". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- 1 2 "Calgary 1988". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ↑ "Yvonne van Gennip". The Beijing Organising Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Albertville 1992". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 400

- ↑ Findling and Pelle (2004), p. 402

- 1 2 "Lillehammer 1994". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ↑ Araton, Harvey (27 February 1994). "Winter Olympics; In Politics and on ice, neighbors are apart". The New York Times (NYTimes.com). Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ↑ "Harding-Kerrigan timeline". The Washington Post (The Washington Post Company). 1 March 1999. Retrieved 20 March 2009. Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - ↑ Barshay, Jill J (3 March 1994). "Figure Skating; It's Stocks and Bouquets as Baiul returns to Ukraine". The New York Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ↑ Phillips, Angus (1 March 1999). "Achievements still burn bright". The Washington Post (The Washington Post Company). Retrieved 20 March 2009. Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - ↑ "Johann-Olav Koss". ESPN.com. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nagano 1998". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ↑ Judd (2008), p. 126

- ↑ "Ten Famous Olympic Skiers". 29 Oct 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ Nevius, C.W. (5 February 1998). ""Clap" Skate draws boos from traditionalists". San Francisco Chronicle (Hearst Communications Inc). Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Salt Lake City 2002". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- ↑ Roberts, Selena (17 February 2002). "The pivotal meeting; French judge's early tears indicating controversy to come". The New York Times (NYTimes.com). Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Bose, Mihir (17 February 2002). "Skating scandal that left IOC on thin ice". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ "Australia win first ever gold". BBC Sport. 17 February 2002. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Turin 2006". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- ↑ Berglund, Nina (20 February 2006). "Canadians hail Norwegian coach's sportsmanship". Aftenposten (Aftenposten.no). Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- ↑ Crouse, Karen (11 December 2009). "Germany’s Claudia Pechstein Tries to Restore Reputation". The New York Times (NYTimes.com). Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ Dunbar, Graham (26 January 2010). "Claudia Pechstein's Doping Appeal Denied". The Huffington Post (HuffingtonPost.com). Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ "Canadian Statistics – Population by selected ethnic origins, by census metropolitan areas (2001 Census)". StatCan. 25 January 2005. Archived from the original on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2006.

- ↑ "Vancouver 2010". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Longman, Jere (13 February 2010). "Quick to Blame in Luge, and Showing No Shame". The New York Times (NYTimes.com). Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ Jones, Tom (28 February 2010). "Best and worst of the Winter Olympics in Vancouver". St. Petersberg Times (Tampabay.com). Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ "Russia's president calls for resignations". ESPN.com. 1 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ Armour, Nancy (28 February 2010). "Surprising success bodes well for South Korea". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Sappenfield, Mark (12 February 2010). "Winter Olympics: Who will win the most medals?". The Christian Science Monitor. CSMonitor.com. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Sochi 2014". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ Pinsent, Matthew (15 October 2011). "Sochi 2014: A look at Russia's Olympic city". BBC News Online. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ Kim, Rose; Moore, Niki (6 July 2011). "Pyeongchang Beats Munich, Annecy to Host 2018 Winter Olympics". Bloomberg.

- 1 2 "Olympics corruption probe ordered". BBC News. 22 December 1998. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Cashmore (2005), p. 444

- ↑ Cashmore (2005), p. 445

- ↑ Cashmore (2003), p. 307

- ↑ Payne (2006), p. 232

- ↑ Miller, Lawrence and McCay (2001), p. 25

- ↑ Abrahamson, Alan (6 December 2003). "Judge Drops Olympic Bid Case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ "Samaranch reflects on bid scandal with regret". Deseret News (WinterSports2002.com). Archived from the original on 26 February 2002. Retrieved 22 March 2002.

- ↑ "Roles and Responsibilities during the Olympic Games" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. January 2010. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Berkes, Howard (1 October 2009). "Olympic Caveat:Host cities risk debt, scandal". National Public Radio. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Payne, Bob (6 August 2008). "The Olympic Effect". MSNBC.com. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ↑ Koba, Mark (11 February 2010). "The money pit that is hosting Olympic Games". CNBC.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Preuss (2004), p. 277

- ↑ Preuss (2004), p. 284

- ↑ Rogge, Jacques (12 February 2010). "Jacques Rogge: Vancouver's Winter Olympic legacy can last for 60 years". The Daily Telegraph (London: Telegraph.co.uk). Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ↑ Yesalis (2000), p. 57

- ↑ The Official Report of XIth Winter Olympic Games, Sapporo 1972 (PDF). The Organising Committee for the Sapporo Olympic Winter Games. 1973. p. 386. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ↑ Hunt, Thomas M. (2007). "Sports, Drugs, and the Cold War" (PDF). Olympika, International Journal of Olympic Studie (International Centre for Olympic Studies) 16 (1): 22. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Mottram (2003), p. 313

- ↑ Mottram (2003), p. 310

- ↑ Yesalis (2000), p. 366

- ↑ "A Brief history of anti-doping". World Anti-Doping Agency. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- 1 2 Macur, Juliet (19 February 2006). "Looking for Doping Evidence, Italian Police Raid Austrians". New York Times (NYTimes.com). Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ↑ "IOC to hold first hearings on doping during 2006 Winter Olympics". USA Today (Gannett Co.). 9 February 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 Cooper-Chen (2005), p. 231

- ↑ Senn (1999), p. 136

- ↑ Senn (1999), p. 136-137

- 1 2 Moreland, Jennifer. "Olympics and Television". The Museum of Broadcast Television. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Gershon (2000), p. 17

- ↑ Barry, (2002), pp. 39–40

- ↑ Cooper-Chen (2005), p. 230

- ↑ Reid, Scott M. (10 February 2010). "Winter Olympics has California flavor". The Orange County Register (Orange County Register Communications). Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- 1 2 Whannel (1992), p. 174

- ↑ Whannel (1992), pp. 174–177

- ↑ Hazan (1982), p. 36

- ↑ Hazan, (1982), p. 42

- ↑ Hazan (1982), p. 44

- ↑ Senn, (1999), p. 171

- ↑ Hill (1992), p. 34

- ↑ Hill (1992), p. 35

- ↑ Hill (1992), pp. 36–38

- ↑ Hill (1992), p. 38

- ↑ Hill (1992), pp. 38–39

- ↑ Hill (1992), p. 48

- ↑ "History of the Winter Olympics". BBC Sport. 5 February 1998. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ↑ Brownell (2005), p. 187

- ↑ The IOC site for the 2002 Winter Olympic Games gives erroneous figure of 77 participated NOCs; however, one can count 78 nations looking through official results of 2002 Games Part 1, Part 2, Part 3. Probably this error is consequence that Costa Rica's delegation of one athlete joined the Games after the Opening Ceremony, so 77 nations participated in Opening Ceremony and 78 nations participated in the Games.

Bibliography

- Barry, Tim; Crawford, Dee (2002). Revise for Advanced PE for Edexcel. Oxford, United Kingdom: Heinemann Educational Publishers. ISBN 0-435-10045-9.

- Brownell, Susan (2008). Beijing's games:What the Olympics mean to China. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Rowman & Littlefield publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-5640-9.

- Cashmore, Ernest (2005). Making sense of sports. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34853-6.

- Cashmore, Ernest (2003). Sports culture. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18169-0.

- Cooper-Chen, Anne (2005). Global entertainment media. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5168-2.

- Findling, John E.; Pelle, Kimberly D. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Modern Olympic Movement. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32278-3.

- Findling, John; Pelle, Kimberly (1996). Historical dictionary of the Modern Olympic Movement. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-28477-6.

- Fry, John (2006). The story of modern skiing. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-58465-489-6.

- Gershon, Richard A. (2000). Telecommunications Management:Industry structures and planning strategies. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-3002-2.

- Guttman, Allen (1986). Sports Spectators. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-06401-2.

- Guttman, Allen (1992). The Olympics, a history of the modern games. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois press. ISBN 0-252-02725-6.

- Hazan, Barukh (1982). Olympic sports and propaganda games. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Inc. ISBN 0-87855-436-X.

- Hill, Christopher R. (1992). Olympic Politics. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3542-2.

- Judd, Ron C. (2008). The Winter Olympics. Seattle, Washington: The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 1-59485-063-1.

- Mallon, Bill; Buchanan, Ian (2006). Historical dictionary of the Olympic Movement. Oxford, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8108-5574-7.

- Mandell, Richard D. (1987). The Nazi Olympics. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01325-5.

- Miller, Toby; Lawrence, Geoffrey; McKay, Jim (2001). Globalization and sport. London: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-7619-5968-8.

- Mottram, David (2003). Drugs in sport. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-27937-2.

- Official Report (1924) of both Summer and Winter games: (ed.) M. Avé, Comité Olympique Français. Les Jeux de la VIIIe Olympiade Paris 1924 – Rapport Officiel (PDF) (in French). Paris: Librairie de France. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- Payne, Michael (2006). Olympic turnaround. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-99030-3.

- Preuss, Holger (2004). The Economics of Staging the Olympics: A Comparison of the Games 1972–2008. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-84376-893-3.

- Schaffer, Kay; Smith, Sidonie (2000). Olympics at the Millennium. Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2820-8.

- Seligmann, Matthew S.; Davison, John; McDonald, John (2003). Daily Life in Hitler's Germany. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-32811-7.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (1999). Power, Politics and the Olympic Games. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics. ISBN 0-88011-958-6.

- Wallechinsky, David; Loucky, Jaime (2010). The complete book of the Winter Olympics (8th ed.). : Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1-55365-502-2.

- Whannel, Garry (1992). Fields in vision television sport and cultural transformation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-05383-8.

- Yesalis, Charles (2000). Anabolic steroids and sports and exercise. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics. ISBN 0-88011-786-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Winter Olympics. |

- Olympic Winter Sports IOC official website

- Winter Olympic Games Venues on Google Maps

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.jpg)