Finite impulse response

In signal processing, a finite impulse response (FIR) filter is a filter whose impulse response (or response to any finite length input) is of finite duration, because it settles to zero in finite time. This is in contrast to infinite impulse response (IIR) filters, which may have internal feedback and may continue to respond indefinitely (usually decaying).

The impulse response (that is, the output in response to a Kronecker delta input) of an Nth-order discrete-time FIR filter lasts exactly N + 1 samples (from first nonzero element through last nonzero element) before it then settles to zero.

FIR filters can be discrete-time or continuous-time, and digital or analog.

Definition

For a causal discrete-time FIR filter of order N, each value of the output sequence is a weighted sum of the most recent input values:

where:

![\scriptstyle x[n]](../I/m/bd7057eebe014d31bdca4d0becd94173.png) is the input signal,

is the input signal,![\scriptstyle y[n]](../I/m/d1a797792abbe276aef200d33157a915.png) is the output signal,

is the output signal, is the filter order; an

is the filter order; an  th-order filter has

th-order filter has  terms on the right-hand side

terms on the right-hand side is the value of the impulse response at the i'th instant for

is the value of the impulse response at the i'th instant for  of an

of an  th-order FIR filter. If the filter is a direct form FIR filter then

th-order FIR filter. If the filter is a direct form FIR filter then  is also a coefficient of the filter .

is also a coefficient of the filter .

This computation is also known as discrete convolution.

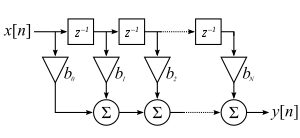

The ![\scriptstyle x[n-i]](../I/m/e9cc2ef41713580a370fa132dbc23fe3.png) in these terms are commonly referred to as taps, based on the structure of a tapped delay line that in many implementations or block diagrams provides the delayed inputs to the multiplication operations. One may speak of a 5th order/6-tap filter, for instance.

in these terms are commonly referred to as taps, based on the structure of a tapped delay line that in many implementations or block diagrams provides the delayed inputs to the multiplication operations. One may speak of a 5th order/6-tap filter, for instance.

The impulse response of the filter as defined is nonzero over a finite duration. Including zeros, the impulse response is the infinite sequence:

If an FIR filter is non-causal, the range of nonzero values in its impulse response can start before n = 0, with the defining formula appropriately generalized.

Properties

An FIR filter has a number of useful properties which sometimes make it preferable to an infinite impulse response (IIR) filter. FIR filters:

- Require no feedback. This means that any rounding errors are not compounded by summed iterations. The same relative error occurs in each calculation. This also makes implementation simpler.

- Are inherently stable, since the output is a sum of a finite number of finite multiples of the input values, so can be no greater than

times the largest value appearing in the input.

times the largest value appearing in the input. - Can easily be designed to be linear phase by making the coefficient sequence symmetric. This property is sometimes desired for phase-sensitive applications, for example data communications, crossover filters, and mastering.

The main disadvantage of FIR filters is that considerably more computation power in a general purpose processor is required compared to an IIR filter with similar sharpness or selectivity, especially when low frequency (relative to the sample rate) cutoffs are needed. However many digital signal processors provide specialized hardware features to make FIR filters approximately as efficient as IIR for many applications.

Frequency response

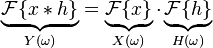

The filter's effect on the sequence x[n] is described in the frequency domain by the convolution theorem:

and

and ![y[n] = x[n]*h[n]= \mathcal{F}^{-1}\big\{X(\omega)\cdot H(\omega)\big\},](../I/m/04c948926d13015ae997683b041d7e3e.png)

where operators  and

and  respectively denote the discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT) and its inverse. Therefore, the complex-valued, multiplicative function

respectively denote the discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT) and its inverse. Therefore, the complex-valued, multiplicative function  is the filter's frequency response. It is defined by a Fourier series:

is the filter's frequency response. It is defined by a Fourier series:

where the added subscript denotes 2π-periodicity. Here  represents frequency in normalized units (radians/sample). The substitution

represents frequency in normalized units (radians/sample). The substitution  favored by many filter design programs, changes the units of frequency

favored by many filter design programs, changes the units of frequency  to cycles/sample and the periodicity to 1.[note 1] When the x[n] sequence has a known sampling-rate,

to cycles/sample and the periodicity to 1.[note 1] When the x[n] sequence has a known sampling-rate,  samples/second, the substitution

samples/second, the substitution  changes the units of frequency

changes the units of frequency  to cycles/second (hertz) and the periodicity to

to cycles/second (hertz) and the periodicity to  The value

The value  corresponds to a frequency of

corresponds to a frequency of  Hz

Hz  cycles/sample, which is the Nyquist frequency.

cycles/sample, which is the Nyquist frequency.

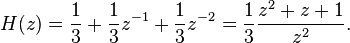

Transfer function

The frequency response can also be written as

can also be written as  where function

where function  is the Z-transform of the impulse response:

is the Z-transform of the impulse response:

z is a complex variable, and H(z) is a surface. One cycle of the periodic frequency response can be found in the region defined by  which is the unit circle of the z-plane. Filter transfer functions are often used to verify the stability of IIR designs. As we have already noted, FIR designs are inherently stable.

which is the unit circle of the z-plane. Filter transfer functions are often used to verify the stability of IIR designs. As we have already noted, FIR designs are inherently stable.

Filter design

An FIR filter is designed by finding the coefficients and filter order that meet certain specifications, which can be in the time-domain (e.g. a matched filter) and/or the frequency domain (most common). Matched filters perform a cross-correlation between the input signal and a known pulse-shape. The FIR convolution is a cross-correlation between the input signal and a time-reversed copy of the impulse-response. Therefore, the matched-filter's impulse response is "designed" by sampling the known pulse-shape and using those samples in reverse order as the coefficients of the filter.[1]

When a particular frequency response is desired, several different design methods are common:

- Window design method

- Frequency Sampling method

- Weighted least squares design

- Parks-McClellan method (also known as the Equiripple, Optimal, or Minimax method). The Remez exchange algorithm is commonly used to find an optimal equiripple set of coefficients. Here the user specifies a desired frequency response, a weighting function for errors from this response, and a filter order N. The algorithm then finds the set of

coefficients that minimize the maximum deviation from the ideal. Intuitively, this finds the filter that is as close as you can get to the desired response given that you can use only

coefficients that minimize the maximum deviation from the ideal. Intuitively, this finds the filter that is as close as you can get to the desired response given that you can use only  coefficients. This method is particularly easy in practice since at least one text[2] includes a program that takes the desired filter and N, and returns the optimum coefficients.

coefficients. This method is particularly easy in practice since at least one text[2] includes a program that takes the desired filter and N, and returns the optimum coefficients. - Equiripple FIR filters can be designed using the FFT algorithms as well.[3] The algorithm is iterative in nature. You simply compute the DFT of an initial filter design that you have using the FFT algorithm (if you don't have an initial estimate you can start with h[n]=delta[n]). In the Fourier domain or FFT domain you correct the frequency response according to your desired specs and compute the inverse FFT. In time-domain you retain only N of the coefficients (force the other coefficients to zero). Compute the FFT once again. Correct the frequency response according to specs.

Software packages like MATLAB, GNU Octave, Scilab, and SciPy provide convenient ways to apply these different methods.

Window design method

In the window design method, one first designs an ideal IIR filter and then truncates the infinite impulse response by multiplying it with a finite length window function. The result is a finite impulse response filter whose frequency response is modified from that of the IIR filter. Multiplying the infinite impulse by the window function in the time domain results in the frequency response of the IIR being convolved with the Fourier transform (or DTFT) of the window function. If the window's main lobe is narrow, the composite frequency response remains close to that of the ideal IIR filter.

The ideal response is usually rectangular, and the corresponding IIR is a sinc function. The result of the frequency domain convolution is that the edges of the rectangle are tapered, and ripples appear in the passband and stopband. Working backward, one can specify the slope (or width) of the tapered region (transition band) and the height of the ripples, and thereby derive the frequency domain parameters of an appropriate window function. Continuing backward to an impulse response can be done by iterating a filter design program to find the minimum filter order. Another method is to restrict the solution set to the parametric family of Kaiser windows, which provides closed form relationships between the time-domain and frequency domain parameters. In general, that method will not achieve the minimum possible filter order, but it is particularly convenient for automated applications that require dynamic, on-the-fly, filter design.

The window design method is also advantageous for creating efficient half-band filters, because the corresponding sinc function is zero at every other sample point (except the center one). The product with the window function does not alter the zeros, so almost half of the coefficients of the final impulse response are zero. An appropriate implementation of the FIR calculations can exploit that property to double the filter's efficiency.

Moving average example

.svg.png)

A moving average filter is a very simple FIR filter. It is sometimes called a boxcar filter, especially when followed by decimation. The filter coefficients,  , are found via the following equation:

, are found via the following equation:

To provide a more specific example, we select the filter order:

The impulse response of the resulting filter is:

The Fig. (a) on the right shows the block diagram of a 2nd-order moving-average filter discussed below. The transfer function is:

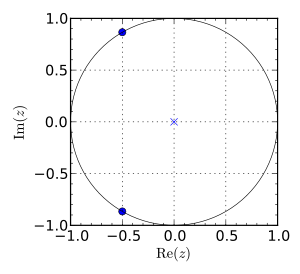

Fig. (b) on the right shows the corresponding pole–zero diagram. Zero frequency (DC) corresponds to (1,0), positive frequencies advancing counterclockwise around the circle to the Nyquist frequency at (-1,0). Two poles are located at the origin, and two zeros are located at  ,

,  .

.

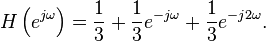

The frequency response, in terms of normalized frequency ω, is:

Fig. (c) on the right shows the magnitude and phase components of  But plots like these can also be generated by doing a discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of the impulse response.[note 2] And because of symmetry, filter design or viewing software often displays only the [0,π] region. The magnitude plot indicates that the moving-average filter passes low frequencies with a gain near 1 and attenuates high frequencies, and is thus a crude low-pass filter. The phase plot is linear except for discontinuities at the two frequencies where the magnitude goes to zero. The size of the discontinuities is π, representing a sign reversal. They do not affect the property of linear phase. That fact is illustrated in Fig. (d).

But plots like these can also be generated by doing a discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of the impulse response.[note 2] And because of symmetry, filter design or viewing software often displays only the [0,π] region. The magnitude plot indicates that the moving-average filter passes low frequencies with a gain near 1 and attenuates high frequencies, and is thus a crude low-pass filter. The phase plot is linear except for discontinuities at the two frequencies where the magnitude goes to zero. The size of the discontinuities is π, representing a sign reversal. They do not affect the property of linear phase. That fact is illustrated in Fig. (d).

Notes

- ↑ A notable exception is MATLAB, which prefers units of half-cycles/sample = cycles/2-samples, because the Nyquist frequency in those units is 1, a convenient choice for plotting software that displays the interval from 0 to the Nyquist frequency.

- ↑ See Sampling the DTFT.

See also

- Electronic filter

- Filter (signal processing)

- Infinite impulse response (IIR) filter

- Z-transform (specifically Linear constant-coefficient difference equation)

- Filter design

- Cascaded integrator–comb filter

- Compact support

Citations

- ↑ Oppenheim, Alan V., Willsky, Alan S., and Young, Ian T.,1983: Signals and Systems, p. 256 (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.) ISBN 0-13-809731-3

- ↑ Rabiner, Lawrence R., and Gold, Bernard, 1975: Theory and Application of Digital Signal Processing (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.) ISBN 0-13-914101-4

- ↑ A. E. Cetin, O.N. Gerek, Y. Yardimci, "Equiripple FIR filter design by the FFT algorithm," IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, pp. 60-64, March 1997.

External links

- Notes on the Optimal Design of FIR Filters Connexions online book by John Treichler (2008).

- FIR FAQ provided by dspguru.com.

- BruteFIR; Software for applying long FIR filters to multi-channel digital audio, either offline or in realtime.

- Freeverb3 Reverb Impulse Response Processor

- Worked examples and explanation for designing FIR filters using windowing. Includes code examples.

- A JAVA applet with different FIR-filters; the filters are applied to sound and the results can be heard immediately. The source code is also available.

- Matlab code; Matlab code for "Equiripple FIR filter design by the FFT algorithm" by A. Enis Cetin, O. N. Gerek and Y. Yardimci, IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 1997.

- EngineerJS FIR filter designer; Online FIR filter designer tool, based on Parks-McClellan method

![\begin{align}

y[n] &= b_0 x[n] + b_1 x[n-1] + \cdots + b_N x[n-N] \\

&= \sum_{i=0}^{N} b_i\cdot x[n-i],

\end{align}](../I/m/2bbe22b6b7ecc8be8b6f74e3fe1dacb0.png)

![h[n] = \sum_{i=0}^{N}b_i\cdot \delta[n-i] =

\begin{cases}

b_n & \scriptstyle 0 \le n \le N\\

0 & \scriptstyle \text{otherwise}.

\end{cases}](../I/m/3afc3f5d41ebda6d3994fdd1569feb63.png)

![H_{2\pi}(\omega)\ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=} \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} h[n]\cdot \left({e^{i \omega}}\right)^{-n} = \sum_{n=0}^{N}b_n\cdot \left({e^{i \omega}}\right)^{-n},](../I/m/3fc2499cf58a6ff81e6178f4858d47dc.png)

![H(z)\ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=} \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} h[n]\cdot z^{-n}.](../I/m/d71f28478b9eeeb76054cc319d79922c.png)

![h[n] = \frac{1}{3}\delta[n] + \frac{1}{3}\delta[n-1] + \frac{1}{3}\delta[n-2]](../I/m/1624bc7c4352ab7f8b541abd9b83012f.png)