Williams tube

| Computer memory types |

|---|

| Volatile |

| RAM |

|

In development |

| Historical |

|

| Non-volatile |

| ROM |

| NVRAM |

| Early stage NVRAM |

| Mechanical |

| In development |

| Historical |

|

The Williams tube, or the Williams–Kilburn tube after inventors Freddie Williams and Tom Kilburn,[1][2] developed in 1946 and 1947, was a cathode ray tube used as a computer memory to electronically store binary data. It was the first random-access digital storage device,[3] and was used successfully in several early computers.

Williams and Kilburn applied for British patents on Dec. 11, 1946[4] and Oct. 2, 1947,[5] followed by US patent applications on Dec. 10, 1947 (U.S. Patent 2,951,176) and May 16, 1949 (U.S. Patent 2,777,971).

Working principle

The Williams tube depends on an effect called secondary emission. When a dot is drawn on a cathode ray tube by a beam of fast-moving electrons, the area of the dot becomes slightly positively charged and the area immediately around it becomes slightly negatively charged, creating a charge well. The charge well remains on the surface of the tube for a fraction of a second, allowing the device to act as a computer memory. The lifetime of the charge well depends on the electrical resistance of the inside of the tube.

The dot can be erased by drawing a second dot immediately next to the first one, thus filling the charge well. Most systems did this by drawing a short dash starting at the dot position, so that the extension of the dash erased the charge initially stored at the starting point.

Information is read from the tube by means of a metal pickup plate that covers the face of the tube. Each time a dot is created or erased, the change in electrical charge induces a voltage pulse in the pickup plate. Since this operation is synchronised with whichever location on the screen is being targeted at that moment, it effectively reads the data stored there. Because the electron beam is essentially inertia-free, and thus can be steered from location to location very quickly, there is no practical restriction in the order of positions so accessed, hence the so-called ″random-access″ nature of the lookup.

Reading a memory location creates a new charge well, destroying the original contents of that location, and so any read has to be followed by a write to reinstate the original data. Since the charge gradually leaked away, it was necessary to scan the tube periodically and rewrite every dot (similar to the memory refresh cycles of DRAM in modern systems).

Some Williams tubes were made from radar-type cathode ray tubes with a phosphor coating that made the data visible, while other tubes were purpose-built without such a coating. The presence or absence of this coating had no effect on the operation of the tube, and was of no importance to the operators since the face of the tube was covered by the pickup plate. If a visible output was needed, a second tube connected in parallel with the storage tube, with a phosphor coating but without a pickup plate, was used as a display device.

Each Williams tube could store about 1024–2560 bits of data.

Development

Developed at the University of Manchester in England, it provided the medium on which the first electronically stored-memory program was implemented in the Manchester Small-Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM) computer, which first successfully ran a program on 21 June 1948.[6] In fact, rather than the Williams tube memory being designed for the SSEM, the SSEM was a testbed to demonstrate the reliability of the memory.[7][8] Tom Kilburn wrote a 17-line program to calculate the highest factor of 218. Tradition at the university has it that this was the only program Kilburn ever wrote.[9]

The Williams tube tended to become unreliable with age, and most working installations had to be "tuned" by hand. By contrast, mercury delay line memory was slower and not truly random access, as the bits were presented serially, which complicated programming. Delay lines also needed hand tuning, but did not age as badly and enjoyed some success in early digital electronic computing despite their data rate, weight, cost, thermal and toxicity problems. However, the Manchester Mark 1, which used Williams tubes, was successfully commercialised as the Ferranti Mark 1. Some early computers in the USA also used the Williams tube, including the IAS machine (originally designed for Selectron tube memory), the UNIVAC 1103, Whirlwind, IBM 701, IBM 702 and the Standards Western Automatic Computer (SWAC). Williams tubes were also used in the Soviet Strela-1 and in the Japan TAC (Tokyo Automatic Computer).

-

A Williams-Kilburn tube

-

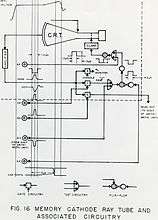

Diagram of Williams tube memory from the 1947 patent

-

SWAC Williams tube assembly

-

Diagram of SWAC Williams tube module

See also

- Atanasoff–Berry computer – Used a type of memory called regenerative capacitor memory

- Mellon optical memory

References

Notes

- ↑ http://www.computer50.org/mark1/notes.html#acousticdelay Why Williams-Kilburn Tube is a Better Name for the Williams Tube

- ↑ Kilburn, Tom (1990), "From Cathode Ray Tube to Ferranti Mark I", Resurrection (The Computer Conservation Society) 1 (2), ISSN 0958-7403, retrieved 15 March 2012

- ↑ "Early computers at Manchester University", Resurrection (The Computer Conservation Society) 1 (4), Summer 1992, ISSN 0958-7403, retrieved 7 July 2010

- ↑ GB Patent 645,691

- ↑ GB Patent 657,591

- ↑ Napper, Brian, Computer 50: The University of Manchester Celebrates the Birth of the Modern Computer, retrieved 26 May 2012

- ↑ Williams, F.C.; Kilburn, T. (Sep 1948), "Electronic Digital Computers", Nature 162 (4117): 487, doi:10.1038/162487a0. Reprinted in The Origins of Digital Computers

- ↑ Williams, F.C.; Kilburn, T.; Tootill, G.C. (Feb 1951), "Universal High-Speed Digital Computers: A Small-Scale Experimental Machine", Proc. IEE 98 (61): 13–28, doi:10.1049/pi-2.1951.0004.

- ↑ Lavington 1998, p. 11

Bibliography

- Lavington, Simon (1998), A History of Manchester Computers (2nd ed.), The British Computer Society, ISBN 978-1-902505-01-5

Further reading

- Bashe, Charles J. (1986). IBM's Early Computers. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-02225-7.

- Lavington, Simon H. (1980). Early British Computers. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-932376-08-8.

- Randell, Brian (1982). The Origins of Digital Computers (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-11319-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Williams tubes. |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||