William Jerome

William Jerome (William Jerome Flannery, September 30, 1865 – June 25, 1932)[1] was an American songwriter, born in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York of Irish immigrant parents, Mary Donnellan and Patrick Flannery. He collaborated with numerous well-known composers and performers of the era, but is best-remembered for his decade-long association with Jean Schwartz with whom he created many popular songs and musical shows in the 1900s and early 1910s.

Early career

By the time he was seventeen, Jerome was singing and dancing in vaudeville. He toured with minstrel shows and performed in blackface.[2] He met Eddie Foy while on tour and they became friends;[3] the two would work together often throughout their careers. By the late 1880s Jerome was performing as a parody-singer at Tony Pastor's.[1] He also began to write songs and his efforts met with some success. In 1891, Jerome composed "He Never Came Back",[4] sung by Foy in the musical Sinbad, which became the hit of the show.[3] Throughout the 1890s he continued to perform, and his reputation as a lyricist grew gradually. He wrote "My Pearl is a Bowery Girl" (1894) with Andrew Mack which became a number one record for Dan W. Quinn.[5]

He met and married another vaudeville singer, Maude Nugent, probably in the early 1890s.[1][lower-alpha 1] He and Nugent had at least one child, Florence, born in 1896.[7]

Jerome is sometimes credited with suggesting the bicycle lyric of "Daisy Bell" (1892) to Harry Dacre.[8]

Collaboration with Schwartz

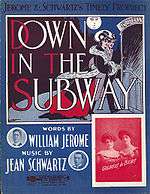

His first collaboration with songwriter Jean Schwartz was the coon song, "When Mr. Shakespeare Comes to Town", in 1901.[1]

The duo came up with "Mr. Dooley", which was interpolated into the 1902 American staging of the London musical A Chinese Honeymoon.[9] Chinese Honeymoon was successful and "Mr. Dooley" became popular. Later that year the song was interpolated into The Wizard of Oz, extending its popularity.[10][lower-alpha 2] "Mr. Dooley" reputedly sold over a million copies.[12] Their next big hit was "Bedelia" (1903). Interpolated into The Jersey Lily and sung by Blanche Ring, it sold over three million copies. By 1904, "Bedelia" had been recorded by four different artists on the three major phonograph labels.[13]

In 1904 they scored the musical Piff! Paff!! Pouf!!!, starring Foy.[9] They went on to score seven more musicals together.[14]

Jerome and Schwartz became two of the best recognized songwriters of the first decade of the 20th century[15] with numerous popular songs to their credit such as "My Irish Molly-O" (1905), "Handle Me With Care" (1907), "Over the Hills and Far Away" and "Meet Me in Rose Time, Rosie" (1908). Although it was not an immediate success, "Chinatown, My Chinatown" (1906) is considered by some to be their biggest hit. Four years after it was written, it was interpolated into Up and Down Broadway by Foy; another five years passed and it became a national hit record.[16] It went on to become a jazz standard.[17]

In 1911, Jerome and Schwartz formed their own sheet music publishing company.[18] They chiefly published titles with music by Schwartz, many with lyrics by Jerome—such as "If It Wasn't for the Irish and the Jews" (1912)[19]—but also many with lyrics by Grant Clarke.[lower-alpha 3] Jerome also began to work more with other composers: in 1912 he wrote the lyrics of "Row, Row, Row" (music by James V. Monaco) for the Ziegfeld Follies;[21] in 1913, he worked with Andrew B. Sterling and Harry Von Tilzer to write lyrics for "On the Old Fall River Line", and with Von Tilzer again on "And the Green Grass Grew All Around". Jerome and Schwartz worked as a team less and less and gradually both moved on.

Later career

After he and Schwartz went their separate ways, Jerome continued to collaborate on songs with some of the best-known composers in the business. In 1920 he wrote the lyrics for "That Old Irish Mother of Mine", music by Von Tilzer, which he dedicated to the memory of his mother. Again with Von Tilzer he wrote "Old King Tut" (1923); with Charles Tobias and Larry Shay he wrote "Get Out and Get Under the Moon" (1928).

He continued to publish sheet music without Schwartz and in 1917 published the enormously successful "Over There" for George M. Cohan; he eventually sold the publishing rights to the song to Leo Feist for $25,000, the most ever paid for a song at the time.[8] On the strength of his Broadway comedy writing credentials, he was recruited by Mack Sennett as a writer for the Keystone Film Company.[22] He was among the first board members (1914–1925) of the American Society of Authors, Composers and Publishers (ASCAP).[23]

William Jerome was struck by a car in the spring of 1932 and died June 25 in Newburgh, New York.[1]

Notes

- ↑ Nugent was also a composer; her most famous song was "Sweet Rosie O'Grady".[6]

- ↑ The lyrics of "Mr. Dooley" were likely inspired by the humorous character of the same name conceived by Finley Peter Dunne.[11]

- ↑ Of the 36 songs published by Jerome & Schwartz in 1912, 30 were composed by Schwartz; of those, 9 were written with Jerome, 11 with Clarke, and one with both Jerome and Clarke.[20]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jasen, David A. (2003). Tin Pan Alley: An Encyclopedia of the Golden Age of American Song. Routledge. pp. 210–211; 345. ISBN 978-1-135-94901-3.

- ↑ Rice, Edward Le Roy (1911). Monarchs of Minstrelsy, from "Daddy" Rice to Date. Kenny Publishing Company. pp. 196; 322.

- 1 2 Fields, Armond (1999). Eddie Foy: A Biography of the Early Popular Stage Comedian. McFarland. pp. 61; 257. ISBN 978-0-7864-4328-4.

- ↑ Jerome, William (1891). "He Never Came Back". Will Rossiter. Retrieved 2015-01-12 – via New York Public Library.

- ↑ Dean, Maury (2003). Rock and Roll. Algora Publishing. p. 549. ISBN 978-0-87586-207-1.

- ↑ Sadie, Julie Anne; Samuel, Rhian (1994). The Norton/Grove Dictionary of Women Composers. W.W. Norton. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-393-03487-5.

- ↑ "Florence Nugent Jerome". Variety XXXI (6). July 11, 1913. Retrieved 2015-01-14.

- 1 2 Sullivan, Steve (2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings. Scarecrow Press. pp. 162; 512. ISBN 978-0-8108-8296-6.

- 1 2 Bordman, Gerald M. (2010). American Musical Theatre: A Chronicle. Oxford University Press. pp. 212; 233. ISBN 978-0-19-972970-8.

- ↑ Swartz, Mark Evan (2002). Oz Before the Rainbow: L. Frank Baum's the Wonderful Wizard of Oz on Stage and Screen to 1939. JHU Press. pp. 58; 87. ISBN 978-0-8018-7092-7.

- ↑ Holloway, Diane (2001). American History in Song: Lyrics From 1900 to 1945. iUniverse. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4697-0453-1.

- ↑ Sanjek, Russell (1988). American Popular Music and Its Business: The First Four Hundred Years. Volume II: From 1790 to 1909. Oxford University Press. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-19-504310-5.

- ↑ Steffen, David J. (2005). From Edison to Marconi: The First Thirty Years of Recorded Music. McFarland. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7864-5156-2.

- ↑ Green, Stanley (2009). Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre. Da Capo Press. p. 371. ISBN 0-7867-4684-X.

- ↑ "Those Two Song-Writers". New York Star. March 6, 1909. p. 15.

- ↑ Ruhlmann, William (2004). Breaking Records: 100 Years of Hits. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-135-94719-4.

- ↑ Crawford, Richard; Magee, Jeffrey (1992). Jazz Standards on Record, 1900–1942: A Core Repertory. Center for Black Music Rsrch. pp. ix; 14. ISBN 978-0-929911-03-8.

- ↑ "Financial News For Printers: Incorporations". Printing Trade News XL (42): 85. October 21, 1911.

- ↑ Garrett, Charles Hiroshi (2008). Struggling to Define a Nation: American Music and the Twentieth Century. University of California Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-520-25486-2.

- ↑ Catalog of Copyright Entries: Musical Compositions. Part 3. Library of Congress. Copyright Office. 1912. p. 1831.

- ↑ Merwe, Ann Ommen van der (2009). The Ziegfeld Follies: A History in Song. Scarecrow Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-4617-3173-3.

- ↑ Walker, Brent E. (2013). Mack Sennett's Fun Factory. McFarland. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7864-7711-1.

- ↑ Pollock, Bruce (2014). A Friend in the Music Business: The ASCAP Story. Hal Leonard. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4803-8609-9.

External links

- "Mr. Dooley", 1902 recording by Dan W. Quinn, at the Library of Congress National Jukebox

- Piff! Paff!! Pouf!!! songbook at the Internet Archive.

- William Jerome at the Internet Broadway Database

- William Jerome (lyricist) at the Discography of American Historical Recordings, University of California, Santa Barbara

- List of popular recordings of Jerome songs at Music VF

|