William Hung (sinologist)

| William Hung | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Native name | 洪業 | ||||||||||||

| Born |

October 27, 1893 Fuzhou, Fujian, Qing Empire | ||||||||||||

| Died |

December 22, 1980 (aged 87) Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States | ||||||||||||

| Nationality | Chinese | ||||||||||||

| Fields | Classical Chinese, Chinese literature | ||||||||||||

| Institutions |

Yenching University Harvard University | ||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Ohio Wesleyan University | ||||||||||||

| Notable students | David Nivison, Teng Ssu-yu, Francis Cleaves | ||||||||||||

| Known for | Harvard Yenching Index Series; Tu Fu: China's Greatest Poet | ||||||||||||

| Notable awards | Prix Stanislas Julien | ||||||||||||

| Spouse | Rhoda Kong | ||||||||||||

| Children | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 洪業 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 洪业 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

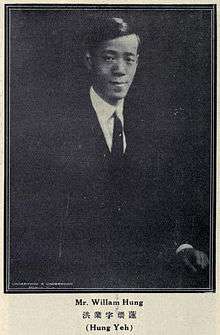

William Hung (Chinese: 洪業; 27 October 1893 – 22 December 1980), was a Chinese educator, sinologist, and historian who taught for many years at Yenching University, Peking, which was China's leading Christian university, and at Harvard University. He is known for bringing modern standards of scholarship to the study of Chinese classical writings, for editing the Harvard-Yenching Index Series, and for his biography, Tu Fu: China's Greatest Poet. He became a Christian while a student at the Anglo-Chinese College in Fuzhou, then went to Ohio Wesleyan University, Delaware, Ohio, Columbia University, and Union Theological Seminary. On his return to China, he became Professor and Dean of Yenching University, where he was instrumental in establishing the Harvard-Yenching Institute.[1] He came to Harvard in 1946 and spent the rest of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, teaching and mentoring students.

William Hung was the oldest of six children. His father gave him the "school name" Hong Ye ("Great Enterprise"), and then when he left for the United States he took the given name William. He married Rhoda Kong in 1919, and the couple had two children, Ruth and Gertrude.

Family and education

William Hung was born on 27 October 1893 in Fuzhou. In 1901 Hung traveled with his family from Fuzhou to Shandong, where Hung's father was a county magistrate for the Qing government. He began his Confucian studies there at the age of four, but soon also began to read traditional novels.[2] He entered the Shandong Teachers College after scoring number one on the entrance exam. He was awarded a monthly stipend of two taels of silver, but was forced to transfer to a Resident Guest School because the local Shandong students taunted him for his southern accent and resented the advantage of his head start in Confucian learning.[3]

On his return to Fuzhou, he entered the Anglo-Chinese College, a Christian school run by Methodist missionaries. Christianity, however, had little initial appeal. Hung set out to persuade his fellow students this foreign doctrine was inferior to Confucian teachings by publicly comparing the "worst parts" of Christianity to the "best parts" of the Chinese classics. He escaped expulsion only when the principal's wife, Elizabeth Gowdy, came to his defense.[4] In response to Hung's request to return and help defend Confucianism against the foreigners, Hung's father returned to Fuzhou. When he visited the cemetery to pay respects to the family graves, he caught pneumonia and died. Hung was devastated. Mrs. Gowdy won him to Christianity when she explained she did not believe the concept popular among some Christians, namely good heathen men such as Hung's father would go to hell, or, for that matter, she was not sure there was such a place. The Bible, she argued, was like a feast at which you would choose which food that was healthy and attractive and which was not; in reading the Bible you should pay attention to the parts you found beneficial, not the contradictions and mistakes that had also accumulated over the centuries. Hung, who had also heard the liberal Sherwood Eddy preach, was converted to this liberal interpretation of the Christian message.[5]

After graduating in 1916, Hung's knowledge of English and German gave him the choice of several jobs in government agencies dealing with foreigners, but a wealthy American wrote from St. Louis offering to pay for his study in the United States. The Fuzhou Methodist Bishop James Bashford recommended Hung enroll at the Ohio Wesleyan University, where he obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1917. In 1919, Hung obtained a master's degree from Columbia University, where he studied under James Harvey Robinson, leader of the New History, and in 1920, a degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York.[6]

In 1919, Hung, through their common work with the Chinese Students' Association and the Intercollegiate YMCA, met Rhoda Kong, who had left China at an early age and grown up in Hawaii. They soon married, and their two children, Gertrude and Ruth, were born in 1919 and 1921.[7]

From 1921 to 1922, Hung served as Chinese Secretary for the Board of Foreign Missions of Methodist Episcopal Church giving more than one hundred lectures throughout the United States. Once, when he had finished his talk, a member of the audience told him that his speech was so exciting that should take this as a career. Hung was personable, funny and succinct and soon became a popular figure on the lecture circuit. In 1922, Hung taught at DePauw University, in Indiana as Horizon Lecturer, and In 1923 he became the Acting Head of the History Department of Yenching University.[8]

While in the United States, Hung became a member of the New York City Civic Club, the Clergy Club, the China Institute, and Phi Beta Kappa. He also joined the American Historical Association and the Berlin Gesellschaft Fur Kirchengeschichte (Church History Society).[1]

Career at Yenching and the Harvard-Yenching Institute

Yenching University, which had opened in 1919, under the leadership of President John Leighton Stuart set out to become the leading Christian university in China. Hung was one of the first scholars trained in the West Stuart recruited. Hung joined Yenching in 1922 as a part-time lecturer in history, also serving as the Chinese pastor in a Methodist mission for students from Fujian in Peking. As he became a full-time instructor, then head of the department, and then Dean of the college his strong ambition was to make the History Department known for combining knowledge of classical Chinese sources with up to date training in western scholarship. He announced his ambition to raise Yenching's academic quality and to "make it the peer of Peita" (Peking University).[9]

The establishment of the Harvard-Yenching Institute was a major project for Hung and President Stuart. An American industrialist had bequeathed a substantial endowment for the support of Christian higher education in Asia, but Harvard had moved to use it to establish Chinese studies on its own campus, with a supporting program in Peking. Stuart and Hung were determined to make Yenching the home for the Chinese side of the new development though Harvard leaders were leaning toward Peking University on the assumption a Christian missionary university would be second rate.[10] In the end, Harvard agreed to make Yenching their partner, but not before Hung helped to overcome a possible stumbling block. In 1925, a Yenching student named Wang came to Hung's campus residence late at night to report a matter of patriotic concern. The previous year Wang had acted as interpreter for Langdon Warner, a Harvard professor of art history who had been travelling on an exploratory trip to the cave libraries at Dunhuang. Wang had accidentally come across Warner experimenting with cheesecloth and glycerin to remove unique murals, and now Wang reported Warner had returned with a large supply of those materials.[11] Knowing Warner was a key negotiator for Harvard and he was in secret talks with nearby Peking University, Hung instructed Wang to act as if nothing had happened, but also arranged with a colleague in the Ministry of Education to instruct every local official along the route Warner was to be warmly welcomed, but never left alone at any historic site.[12]

By 1927 Hung felt he could brag Yenching no longer had to "share the disgrace of inferior Chinese courses, a charge so frequently made against missionary education institutions."[13] Yet, he resigned as Dean at the height of the Nationalist Party's drive to unite the country, partly because he came to feel he did not have enough time to know the students or faculty, and partly some students felt his methods were too rigid and Americanized. He suspected even President Stuart felt his discipline alienated students who were strong nationalists or communists, perhaps egged on by the older teachers of Chinese.[14]

In 1928, as part of the new Institute's activities, Harvard University invited Hung to Cambridge, where he offered "The Far East Since 1793." Though it was taught in the Department of Far Eastern Languages, not the Department of History, it the first survey course of Chinese history to be taught at Harvard.[15] The following year he returned to Yenching to resume his leadership of the Department of History and the Institute of Chinese Studies, and was in charge of Harvard-Yenching Institute grants.[8]

Sinology and teaching in the 1930s

In the 1930s, Hung put his energies into training students and publishing his research. He often met with students at his campus home, which was built to his specifications with an entrance directly into his study, so as not to disturb his family. His bibliography lists more than forty publications after he left the Yenching administration.[16] During his stay at Harvard, Hung had found the lack of bibliographies and indexes an obstacle to training students in Sinology. He determined to use scientific methods to establish reliable texts and create indexes to the most important classical works. Hung wrote introductions to the indexes which were in many cases the most thorough studies on the subject. The series eventually totaled sixty-four volumes. Hung won the 1937 Prix Stanislas Julien for the preface to the Liji index, becoming the second Chinese to receive this award. An even more ambitious project was the preface to the concordance for the Spring and Autumn Annals, a work which Confucius had been credited with editing centuries after its composition. By showing solar eclipses in the text corresponded to modern calculations, Hung demonstrated the work was a true record of its time, not a later text. Hung finished work on the volume while Japanese war planes dropped their bombs only a few hundred yards from the Yenching campus.[17]

Among the students Hung trained at Yenching in these years were many who went on to teach at American universities, including Kenneth K.S. Chen, Fang Chao-ying, Tu Lien-chieh, James T.C. Liu, and Teng Ssu-yu.[18]

After the Japanese Army captured Peking in July 1937, Hung continued his sinological research under increasingly difficult circumstances. In 1940, at the age of 47, Hung published Index to Du Fu's Poetry. In 1940 Hung returned to Ohio Wesleyan to accept an honorary doctorate. In 1941, the Japanese Army occupied the Yenching campus. Hung and his colleagues secretly worked at the Sino-French University (中法大学, l'Université Franco-Chinoise) to publish several further volumes in the index series.[8]

When war with the United States was declared in December 1941, the Japanese army arrested 12 Yenching University professors, including Hung. They were roughly interrogated, beaten, kept in unheated cells, and fed little. Although they were eventually released, they were not allowed to return to campus. Hung refused to cooperate with the Japanese.[19]

After the war

After the Allied victory in August 1945, Hung returned to the devastated Yenching campus. He thought of going to the United States, first to catch up with scholarly developments and secondly to seek support for Yenching. Harvard University invited him to lecture and Hung left China in April 1946. The University of Hawaii hired him in the spring of 1947 as visiting professor. While he still intended to return to China, Civil War had broken out and the economy deteriorated sharply. That summer, he decided to move back to the Harvard–Yenching Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts and, with the outbreak of the Korean War, Hung completely abandoned the idea of returning to China.[8]

The decision to give up home and Yenching University made him miserable but he felt his will has been exhausted. At the age of fifty, he had to find the courage to meet the challenges of an unknown world. In 1948, the Harvard-Yenching Institute made him a Fellow but did not give him a formal teaching position. Hung and his wife bought a house close by the university, and rented out rooms and collected meager social benefits to survive. While living abroad, Hung still longed for his homeland. He often told friends "I love America, I love the motherland, the motherland of my parents."[8]

In 1952 Harvard University Press published his Tu Fu: China's Greatest Poet He became Nanyang University of Singapore Board member in 1958. Hung offered Du Fu classes or lectures at Harvard, Yale University, the University of Pittsburgh, University of Hawaii.[20]

Among the scholars he influenced with his teaching and attention were David Nivison and Joseph Fletcher. Francis Cleaves, whom he had met in China before the war, became a close friend in Cambridge. Every afternoon at three, the two would meet and have tea. Cleaves, a specialist in Mongolian, introduced Hung to The Secret History of the Mongols. Cleaves disagreed with the conclusions in Hung's article on the transmission of the text, but out of a sense of respect did not publish his own translation until after Hung's death.[21]

Old age

Hung Ye lived in Cambridge and was actively involved a prayer fellowship in New York. He also informally assisted Harvard East Asian Studies.Living abroad, he said looking back at his life: "In my life of scholarship, my method was the scientific method and I am completely confident that it was not wrong." At the age of 86, when he mounted the podium to lecture for the last time, he said "Now the 'Gang of Four' has been overthrown, there can be academic engagement with tradition."[8]

In March 1980, Hung fell during his morning exercises, resulting in a fractured elbow, then physical deterioration. The night of December 16, Hung suffered sudden confusion, talking with the people around him in the Fuzhou dialect. On December 22, 1980, Hung died at the age of 87.[8]

Selected works

- Hung, William. Harvard-Yenching Institute Sinological Index Series 哈佛燕京大學圖書館哈佛燕京大學圖書館引得編纂處編纂處 (Hafo Yanjing daxue tushuguan yinde bianzuan chu). Beiping: Harvard-Yenching Institute, 1931-.; reprint Ch'eng-wen, Distributed by Chinese Materials and Research Aids Service Center, Taipei, Taiwan, 1966. 41 volumes.

- —— (1934), Ho Shen and Shu-Oh'un-Yuan;: An Episode in the Past of the Yenching Campus, Peiping: Office of the President, Yenching University

- —— (1932). As It Looks to Young China : Chapters by a Group of Christian Chinese. New York: Friendship Press.

- —— (1952). Tu Fu: China's Greatest Poet. Cambridge,: Harvard University Press.

- —— (1955). "Huang Tsun-Hsien's Poem "The Closure of the Educational Mission in America"". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 18 (1/2): 50–73.

- —— , (1981) 洪業論學集 (Hong Ye Lun Xue Ji) Beijing: ZhongHua shu ju: XinHua.

Notes

- 1 2 Who's Who in China, 3rd ed. Shanghai: The China Weekly Review. 1925.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 5–8,21.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 33–37.

- ↑ West (1976), pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 41–43.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 64, 85.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 包丽敏,洪业:要进步先要往后走,人民网,2006年01月18日

- ↑ West (1976), p. 74-76.

- ↑ Fan (2014), pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Fan (2014), pp. 14–19.

- ↑ West (1976), p. 122.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 108–110.

- ↑ Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations Harvard University

- ↑ Hung (1962).

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 140–143.

- ↑ Egan (1987), p. 206.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 159–170.

- ↑ Egan (1987), p. 206.

- ↑ Egan (1987), pp. 201–202.

References

- Egan, Susan Chan (1987). A Latterday Confucian: Reminiscences of William Hung, (1893-1980). Cambridge, Mass.: Council on East Asian Studies, Distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674512979.

- Fan, Shuhua (2014). The Harvard-Yenching Institute and Cultural Engineering: Remaking the Humanities in China, 1924-1951. ISBN 9780739168509.

- Hung, William (1962). "An Annotated, Partial List of the Publications of William Hung". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 24: 7–16. JSTOR http://www.jstor.org/stable/2718644.

- West, Philip (1976). Yenching University and Sino-Western Relations, 1916-1952. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Further reading

- 王鈡翰 (Wang, Zhonghan), 姚念兹 (Yao Nianzi), and 达力扎布 (Dalizhabu) (1996). 洪业, 杨联陞卷 (Hong Ye, Yang Liansheng Juan). Shijiazhuang Shi: Hebei jiao yu chu ban she. ISBN 7543429152.

External links

- Hung, William 1893-1980 WorldCat Authority Page