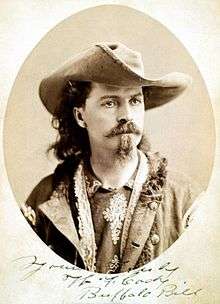

Buffalo Bill

| Buffalo Bill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

William Frederick Cody February 26, 1846 Le Claire, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died |

January 10, 1917 (aged 70) Denver, Colorado, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Kidney failure |

| Resting place |

Lookout Mountain, Golden, Colorado 39°43′57″N 105°14′17″W / 39.73250°N 105.23806°W |

| Other names | Buffalo Bill Cody |

| Occupation | Army scout, Pony Express rider, ranch hand, wagon train driver, buffalo hunter, fur trapper, gold prospector, showman |

| Known for | Buffalo Bill Wild West shows which provided education and entertainment about bronco riding, handling bovine and equine livestock, roping, and other herdsmen skills seen in present day rodeos |

| Spouse(s) | Louisa Frederici (1843–1921) (m. 1866–1917) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

| Signature | |

| |

William Frederick "Buffalo Bill" Cody (February 26, 1846 – January 10, 1917) was an American scout, bison hunter, and showman. He was born in the Iowa Territory (now the U.S. state of Iowa) in Le Claire but he grew up for several years in his father's hometown in Canada before his family moved to the Kansas Territory.

Buffalo Bill started working at the age of eleven after his father's death, and became a rider for the Pony Express at age 14. During the American Civil War, he served for the Union from 1863 to the end of the war in 1865. Later he served as a civilian scout to the US Army during the Indian Wars, receiving the Medal of Honor in 1872.

One of the most colorful figures of the American Old West, Buffalo Bill started performing in shows that displayed cowboy themes and episodes from the frontier and Indian Wars. He founded his Buffalo Bill's Wild West in 1883, taking his large company on tours throughout the United States and, beginning in 1887, in Great Britain and Europe.

Early life and education

William Frederick Cody was born on February 26, 1846 on a farm just outside Le Claire, Iowa.[1] His father Isaac was born on September 5, 1811, in Toronto Township, Upper Canada, now part of Mississauga, Ontario, directly west of Toronto. Mary Ann Bonsell Laycock, Cody's mother, was born about 1817 in New Jersey, near Philadelphia. After Mary Laycock moved to Cincinnati to teach school, she met and married Isaac Cody. She was a descendant of Josiah Bunting, a Quaker who had settled in Pennsylvania. There is no historical evidence to indicate Buffalo Bill was raised as a Quaker.[2] In 1847 the couple moved to Ontario, having their son baptized in 1847, as William Cody, at the Dixie Union Chapel in Peel County (present-day Peel Region, of which Mississauga is part), not far from his father's family's farm. The Chapel was built with Cody money, and the land was donated by Philip Cody of Toronto Township.[3] They lived in Ontario for several years.

In 1853, Isaac Cody sold his land in rural Scott County, Iowa for $2000, and he and his family moved to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Territory.[1] In these years before the Civil War, Kansas was overtaken by political and physical conflict related to the slavery question. Isaac Cody was against slavery. He was invited to speak at Rively's store, a local trading post where pro-slavery men often held meetings. His antislavery speech so angered the crowd that they threatened to kill him if he didn't step down. One man jumped up and stabbed Cody twice with a bowie knife. Rively, the store's owner, rushed Isaac Cody to get treatment, but he never fully recovered from his injuries.

In Kansas, the family was frequently persecuted by pro-slavery supporters. Cody's father spent time away from home for his own safety. His enemies learned of a planned visit to his family and plotted to kill him on the way. The young Cody, despite his youth and being ill at the time, rode 30 miles (48 km) to warn his father. Cody's father went to Cleveland, Ohio to organize a colony of thirty families to bring back to Kansas, in order to add to the anti-slavery population. During his return trip he caught a respiratory infection which, compounded by the lingering effects of his stabbing and complications from kidney disease, led to Isaac Cody's death in April 1857.[4][5]

After the father's death, the Cody family suffered financially. At age 11, Bill Cody took a job with a freight carrier as a "boy extra." On horseback he would ride up and down the length of a wagon train, and deliver messages between the drivers and workmen. Next he joined Johnston's Army as an unofficial member of the scouts assigned to guide the United States Army to Utah, to put down a rumored rebellion by the Mormon population of Salt Lake City.[5]

According to Cody's account in Buffalo Bill's Own Story, the Utah War was where he first began his career as an "Indian fighter":

- Presently the moon rose, dead ahead of me; and painted boldly across its face was the figure of an Indian. He wore this war-bonnet of the Sioux, at his shoulder was a rifle pointed at someone in the river-bottom 30 feet (9 m) below; in another second he would drop one of my friends. I raised my old muzzle-loader and fired. The figure collapsed, tumbled down the bank and landed with a splash in the water. "What is it?" called McCarthy, as he hurried back. "It's over there in the water." "Hi!" he cried. 'Little Billy's killed an Indian all by himself!' So began my career as an Indian fighter.

At the age of 14, in 1860 Cody was struck by gold fever, with news of gold at Fort Collins, Colorado and the Holcomb Valley Gold Rush in California,[6] but on his way to the gold fields, he met an agent for the Pony Express. He signed with them, and after building several stations and corrals, Cody was given a job as a rider. He worked at this until he was called home to his sick mother's bedside.[7]

Military service

| Private William Frederick Cody Chief of Scouts | |

|---|---|

William Cody (Medal of Honor recipient) | |

| Born |

February 26, 1846 Le Claire, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died |

January 10, 1917 (aged 70) Denver, Colorado, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | US Army |

| Years of service | 1863-1865, 1868-1872 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit | Third Cavalry, 7th Kansas Cavalry (Company H) |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War, Indian Wars (16 battles total) |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

| Spouse(s) | Louisa Frederici (1843–1921) (m. 1866–1917) |

| Other work | Pony Express rider, hunter, showman |

After his mother recovered, Cody wanted to enlist as a soldier in the Union Army during the American Civil War, but was refused because of his young age. He began working with a United States freight caravan that delivered supplies to Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming. In 1863 at age 17, he enlisted as a teamster with the rank of private in Company H, 7th Kansas Cavalry and served until discharged in 1865.[5][7]

The next year, Cody married Louisa Frederici. They had four children. Two died young when the family was living in Rochester, New York. They and a third child are buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, in the City of Rochester.[8]

Cody went back to work for the Army in 1868[9] and was Chief of Scouts for the Third Cavalry during the Plains Wars. Part of the time, he scouted for Indians and fought in 16 battles;[9] at other times, he hunted and killed bison to supply the Army and the Kansas Pacific Railroad. In January 1872, Cody was a scout for Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia's highly publicized royal hunt.[10]

William F. Cody received the medal in 1872 for gallantry as an Army scout in the Indian wars.

But it was revoked in 1917, along with medals of 910 other recipients, when Congress retroactively changed the rules for the honor. Congress stated that only military personnel could receive the award. Even though he was a Army veteran he was awarded the medal for service as a civilian scout, in all, five scouts lost medals in 1917.

However, in 1989 the Army Board for Correction of Military Records ruled that Cody and the four other scouts are nonetheless deserving of the honor and restored their names to Medal of Honor roll.

Cody claimed to have had many other jobs, including as a trapper, bullwhacker, "Fifty-Niner" in Colorado, a Pony Express rider in 1860, wagonmaster, stagecoach driver, and a hotel manager, but historians have since had difficulty documenting them. He may have fabricated some for publicity.[11]

Nickname

"Buffalo Bill" got his nickname after the American Civil War, when he had a contract to supply Kansas Pacific Railroad workers with buffalo meat.[12] Cody is purported to have killed 4,282 American bison (commonly known as buffalo) in eighteen months, (1867–1868).[7] Cody and hunter William Comstock competed in an eight-hour[9] buffalo-shooting match over the exclusive right to use the name, in which Cody won by killing 68 bison to Comstock's 48.[13] Comstock, part Cheyenne and a noted hunter, scout, and interpreter, used a fast-shooting Henry repeating rifle, while Cody competed with a larger-caliber Springfield Model 1863, which he called Lucretia Borgia after legendary beautiful, ruthless Italian noblewoman, the subject of a popular contemporary Victor Hugo play of the same name. Cody explained that while his formidable opponent, Comstock, chased after his buffalo, engaging from the rear of the herd and leaving a trail of killed buffalo "scattered over a distance of three miles", Cody - likening his strategy to a billiards player "nursing" his billiard balls during "a big run" - first rode his horse to the front of the herd to target the leaders, forcing the followers to one side, eventually causing them to circle and create an easy target, dropping them close together.[14]

The legend is born

In 1869, Cody met Ned Buntline. Afterward, Buntline published a story for Street and Smith's New York Weekly which was based on Cody's adventures (largely made up by Buntline). Then Buntline published a highly successful novel, Buffalo Bill, King of the Bordermen. Many other sequels followed, by Buntline, Prentiss Ingraham and others from 1870s through the early part of the twentieth century.[15] Cody became world famous for his Wild West Shows, which toured in Great Britain and Europe. Audiences were enthusiastic about seeing a piece of the American West.[16] Emilio Salgari, a noted Italian writer of adventure stories, met Buffalo Bill when he came to Italy and saw his show; Salgari later featured Cody as a hero in some of his novels.

Buffalo Bill's Wild West

In December 1872, Cody traveled to Chicago to make his stage debut with friend Texas Jack Omohundro in The Scouts of the Prairie, one of the original Wild West shows produced by Ned Buntline.[17] During the 1873–1874 season, Cody and Omohundro invited their friend James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok to join them in a new play called Scouts of the Plains.[18]

The troupe toured for ten years. Cody's part typically included an 1876 incident at the Warbonnet Creek, where he claimed to have scalped a Cheyenne warrior.[19]

In 1883, in the area of North Platte, Nebraska, Cody founded "Buffalo Bill's Wild West", a circus-like attraction that toured annually.[11] (Despite popular misconception, the word "show" was not a part of the title.)[16] With his show, Cody traveled throughout the United States and Europe and made many contacts. He stayed, for instance, in Garden City, Kansas, in the presidential suite of the former Windsor Hotel. He was befriended by the mayor and state representative, a frontier scout, rancher, and hunter named Charles "Buffalo" Jones.[20]

In 1893, Cody changed the title to "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World". The show began with a parade on horseback, with participants from horse-culture groups that included US and other military, cowboys, American Indians, and performers from all over the world in their best attire.[11] Turks, Gauchos, Arabs, Mongols and Georgians, displayed their distinctive horses and colorful costumes. Visitors would see main events, feats of skill, staged races, and sideshows. Many historical western figures participated in the show. For example, Sitting Bull appeared with a band of 20 of his braves.

Cody's headline performers were well known in their own right. People such as Annie Oakley and her husband Frank Butler did sharp shooting, together with the likes of Gabriel Dumont, not to mention Lillian Smith. Performers re-enacted the riding of the Pony Express, Indian attacks on wagon trains, and stagecoach robberies. The show was said to end with a re-enactment of Custer's Last Stand, in which Cody portrayed General Custer, but this is more legend than fact. The finale was typically a portrayal of an Indian attack on a settler's cabin. Cody would ride in with an entourage of cowboys to defend a settler and his family. This finale was featured predominantly as early as 1886, but vanished after 1907; in total, it was used in 23 of 33 tours.[21] Another celebrity appearing on the show was Calamity Jane, as a storyteller as of 1893. The show influenced many 20th-century portrayals of "the West" in cinema and literature.[16]

_edit.jpg)

With his profits, Cody purchased a 4,000-acre (16 km2) ranch near North Platte, Nebraska, in 1886. Scout's Rest Ranch included an eighteen-room mansion and a large barn for winter storage of the show's livestock.

In 1887, Cody took the show to Great Britain in celebration of the Jubilee year of Queen Victoria. Queen Victoria attended a performance.[11] It played in London before going on to Birmingham and Salford near Manchester, where it stayed for five months.[22]

In 1889, the show toured Europe, and in 1890 Cody met Pope Leo XIII. On 8 March 1890, a competition took place. Buffalo Bill had met some of the Italian "butteri" (a less-well known sort of Italian equivalent of cowboys) and said his men were more skilled at roping calves and performing other similar actions. A group of Buffalo Bill's men challenged nine butteri, led by Augusto Imperiali, at Prati di Castello neighbourhood in Rome. The Italian butteri easily won the competition. Augusto Imperiali became a sort of local hero after the event: a street and a monument were dedicated to him in his home town (Cisterna di Latina), and in the 1920s and 1930s, he was featured as the hero in a series of comic strips.

Cody set up an independent exhibition near the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, which greatly contributed to his popularity in the United States.[11] It vexed the promoters of the fair, who had first rejected his request to participate..

On October 29, 1901 outside Lexington, North Carolina, a freight train crashed into one unit of the train carrying Buffalo Bill's show from Charlotte, North Carolina to Danville, Virginia. The freight train's engineer had thought that the entire show train had passed, not realizing it was three units, and returned to the tracks. 110 horses were killed by the accident or had to be put down later. These included "Old Pap" and "Old Eagle". No people were killed but Annie Oakley's injuries were so severe that she was told she would never walk again. She did recover and continued performing later. The incident put the show out of business for a while and the major disruption may have led to its eventual demise.[23]

In 1908, Pawnee Bill and Buffalo Bill joined forces and created the "Two Bills" show. That show was foreclosed on when it was playing in Denver, Colorado.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Tours Europe

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West toured Europe eight times, the first four tours between 1887 and 1892, and the last four from 1902 to 1906.[24]

The Wild West first went to London in 1887 as part of the American Exhibition,[25] which coincided with the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, requested a private preview of the Wild West performance; he was impressed enough to arrange a command performance for Queen Victoria. The Queen enjoyed the show and meeting the performers, setting the stage for another command performance on June 20, 1887 for her Jubilee guests. Royalty from all over Europe attended, including the future Kaiser Wilhelm II and future King George V.[26] These royal encounters provided Buffalo Bill’s Wild West an endorsement and publicity that ensured its success. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West closed its successful London run in October 1887 after more than 300 performances, with more than 2.5 million tickets sold.[27] The tour made stops in Birmingham and Manchester before returning to the U.S. in May 1888 for a short summer tour.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West returned to Europe in May 1889 as part of the Exposition Universelle in Paris, France, an event that commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille and featured the debut of the Eiffel Tower.[28] The tour moved to the South of France and Barcelona, Spain, then on to Italy. While in Rome, a Wild West delegation was received by Pope Leo XIII.[29] Buffalo Bill was disappointed that the condition of the Colosseum did not allow it to be a venue; however, at Verona, the Wild West did perform in the ancient Roman amphitheater.[30] The tour finished with stops in Austria-Hungary and Germany.

In 1891 the show toured cities in Belgium and the Netherlands before returning to Great Britain to close the season. Cody depended on a number of staff to manage arrangements for touring with the large and complex show: in 1891 Major Burke was the general manager for the Buffalo Bill Wild West Company; William Laugan (sic), supply agent; George C. Crager, Sioux interpreter, considered leader of relations with the Indians; and John Shangren, a native interpreter.[31] In 1891, Buffalo Bill performed in Karlsruhe, Germany, in the Südstadt Quarter. The inhabitants of Südstadt are nicknamed "Indianer" (German for American Indians) to this day and the best accepted theory says that this is due to Buffalo Bill's show.

The show's 1892 tour was confined to Great Britain; it featured another command performance for Queen Victoria. The tour finished with a six-month run in London before leaving Europe for nearly a decade.[32]

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West returned to Europe in December 1902 with a fourteen-week run in London, capped by a visit from King Edward VII and the future King George V. The Wild West traveled throughout Great Britain during the 1902-03 tour as well as the 1904 tour, performing in nearly every city large enough to support it.[33] The 1905 tour began in April with a two-month run in Paris before moving into the rest of France, where it performed mostly one-night stands, concluding in December. The final tour of 1906 began in France on March 4, and quickly moved on to Italy for two months. The Wild West traveled east: performing in Austria, the Balkans, Hungary, Romania, and the Ukraine, before returning west to tour in Poland, Bohemia (later Czech Republic), Germany, and Belgium.[34]

The show was enormously successful in Europe, making Cody an international celebrity and an American icon.[35] Mark Twain commented, "...It is often said on the other side of the water that none of the exhibitions which we send to England are purely and distinctly American. If you will take the Wild West show over there you can remove that reproach."[36] The Wild West brought an exotic foreign world to life for its European audiences, allowing a last glimpse at the fading American frontier.

Several members of the Wild West show died of accidents or disease during these tours in Europe:

- Surrounded by the Enemy {Oglala Lakota} b. 1865-d. December 1887, from a lung infection. His remains were buried at Brompton Cemetery.[37] Little Chief and Good Robe's one-year-old son Red Penny had died four months earlier. He was buried in that same cemetery.

- Paul Eagle Star {Brulé Lakota} b.1864-d. August 24, 1891 in Sheffield, from tetanus and complications due to his horse falling on him and breaking his leg. He was buried in Brompton Cemetery.[31] His remains were exhumed in March 1999 and transported to South Dakota's Rosebud Indian Reservation by his two grandchildren, Moses and Lucy Eagle Star II. Eagle Star's reburial occurred in Rosebud's Lakota cemetery two months later.

- Long Wolf {Oglala Lakota} b. 1833-d. June 11, 1892 from pneumonia; originally buried in Brompton Cemetery. His remains were exhumed and transported to South Dakota's Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in September 1997 by descendants including his great-grandson, John Black Feather.[38] Long Wolf's reburial occurred at Saint Ann's Cemetery in Denby.

- White Star Ghost Dog {Oglala Lakota} b.1890-d. August 17, 1892, from a horse riding accident; originally buried in Brompton Cemetery. Her remains were exhumed and transported to South Dakota's Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in September 1997 along with those of Long Wolf. Her reburial occurred at Saint Ann's Cemetery in Denby.

Life in Cody, Wyoming

In 1895, Cody was instrumental in the founding of Cody, the seat of Park County in northwestern Wyoming. Today the Old Trail Town museum is at the center of the community and honors the traditions of Western life. Cody first passed through the region in the 1870s. He was so impressed by the development possibilities from irrigation, rich soil, grand scenery, hunting, and proximity to Yellowstone Park that he returned in the mid-1890s to start a town. Streets in the town were named after his several associates: Beck, Alger, Rumsey, Bleistein and Salsbury. The town was incorporated in 1901.

In November 1902, Cody opened the Irma Hotel, which he named after his daughter. He envisioned that a growing number of tourists would be coming to Cody via the recently opened Burlington rail line. He expected that they would proceed up the Cody Road along the North Fork of the Shoshone River to visit Yellowstone Park. To accommodate travelers, Cody completed construction of the Wapiti Inn and Pahaska Tepee in 1905 along the Cody Road [39] with the assistance of artist and rancher Abraham Archibald Anderson.

Cody established the TE Ranch, located on the South Fork of the Shoshone River about thirty-five miles from Cody. When he acquired the TE property, he stocked it with cattle sent from Nebraska and South Dakota. His new herd carried the TE brand. The late 1890s were relatively prosperous years for "Buffalo Bill's Wild West", and he bought more land to add to the TE Ranch. Eventually Cody held around 8,000 acres (32 km²) of private land for grazing operations and ran about 1,000 head of cattle. He operated a dude ranch, pack horse camping trips, and big game hunting business at and from the TE Ranch. In his spacious ranch house, he entertained notable guests from Europe and America.

Irrigation

Larry McMurtry, along with historians such as R.L. Wilson, asserts that at the turn of the 20th century, Buffalo Bill Cody was the most recognizable celebrity on Earth.[16] While Cody's show brought appreciation for the Western and American Indian cultures, he saw the American West change dramatically during his life. Bison herds, which had once numbered in the millions, were threatened with extinction. Railroads crossed the plains, barbed wire and other types of fences divided the land for farmers and ranchers, and the once-threatening Indian tribes were confined to reservations. Wyoming's resources of coal, oil and natural gas were beginning to be exploited toward the end of his life.[16]

The Shoshone River was dammed for hydroelectric power as well as for irrigation. In 1897 and 1899 Cody and his associates acquired from the State of Wyoming the right to take water from the Shoshone River to irrigate about 169,000 acres (680 km2) of land in the Big Horn Basin. They began developing a canal to carry water diverted from the river, but their plans did not include a water storage reservoir. Cody and his associates were unable to raise sufficient capital to complete their plan. Early in 1903 they joined with the Wyoming Board of Land Commissioners in urging the federal government to step in and help with irrigation development in the valley.

The Shoshone Project became one of the first federal water development projects undertaken by the newly formed Reclamation Service, later to become known as the Bureau of Reclamation. After Reclamation took over the project in 1903, investigating engineers recommended constructing a dam on the Shoshone River in the canyon west of Cody. Construction of the Shoshone Dam started in 1905, a year after the Shoshone Project was authorized. When it was completed in 1910, it was the tallest dam in the world. Almost three decades after its construction, the name of the dam and reservoir was changed to Buffalo Bill Dam by an act of Congress to honor Cody.[40]

His 1879 autobiography is titled The Life and Adventures of Buffalo Bill.[41] A final autobiography, titled "The Great West That Was: 'Buffalo Bill's' Life Story," was serialized in Hearst's International Magazine from August 1916 to July 1917.[42] and ghostwritten by James J. Montague.[43] It contained a number of errors, in part because it was completed after Cody's death in January 1917.[42]

Death

"Buffalo Bill's"

defunct

who used to

ride a watersmooth-silver

stallion

and break onetwothreefourfive pigeonsjustlikethat

Jesus

he was a handsome man

and what i want to know is

how do you like your blueeyed boy

Mister Death

Cody died on January 10, 1917, surrounded by family and friends at his sister's house in Denver. Cody was baptized into the Catholic Church the day before his death by Father Christopher Walsh of the Denver Cathedral.[44][45][46] He received a full Masonic funeral.[47] Upon the news of Cody's death, tributes were made by George V, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and President Woodrow Wilson.[48] His funeral service was in Denver at the Elks Lodge Hall. The Wyoming governor John B. Kendrick, a friend of Cody's, led the funeral procession to the cemetery.

At the time of his death, Cody's once great fortune had dwindled to less than $100,000. He left his burial arrangements up to his wife Louisa. She said that he had always said he wanted to be buried on Lookout Mountain, which was corroborated by their daughter Irma, Cody's sisters, and family friends. But other family members joined the people of Cody to say Buffalo Bill should be buried in the town he founded. The controversy continued.

On June 3, 1917, Cody was buried on Colorado's Lookout Mountain in Golden, west of the city of Denver, on the edge of the Rocky Mountains, overlooking the Great Plains. His burial site was selected by his sister Mary Decker.[49] In 1948 the Cody chapter of the American Legion offered a reward for the "return" of the body, so the Denver chapter mounted a guard over the grave until a deeper shaft could be blasted into the rock.[48]

Philosophy

As a frontier scout, Cody respected Native Americans and supported their rights. He employed many Native Americans, as he thought his show offered them good pay with a chance to improve their lives. He described them as "the former foe, present friend, the American", and once said, "Every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government."[16]

Cody supported the rights of women.[16] He said, "What we want to do is give women even more liberty than they have. Let them do any kind of work they see fit, and if they do it as well as men, give them the same pay."[50]

In his shows, the Indians were usually depicted attacking stagecoaches and wagon trains, from which they were driven off by cowboys and soldiers. Many family members traveled with the men, and Cody encouraged the wives and children of his Indian performers to set up camp – as they would in their homelands – as part of the show. He wanted the paying public to see the human side of the "fierce warriors"; that they had families like any other, and had their own distinct cultures.[16]

Cody was known as a conservationist who spoke out against hide-hunting and pushed for a hunting season.[16]

Freemason

Cody was active in the concordant bodies of Freemasonry, fraternal organization, being initiated in Platte Valley Lodge No. 32, North Platte, Nebraska, on March 5, 1870. He received his 2nd and 3rd degrees on April 2, 1870, and January 10, 1871, respectively. He became a Knight Templar in 1889 and received his 32nd degree in Scottish Rite of Freemasonry in 1894.[47][51]

Legacy and honors

- In 1872, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for service as a civilian scout to the 3rd Cavalry Regiment, for "gallantry in action" at Loupe Forke, Platte River, Nebraska. In 1917, the U.S. Army—after Congress revised the standards for the award—removed from the rolls 911 medals previously awarded either to civilians, or for actions that would not warrant a Medal of Honor under the new higher standards. Among those revoked was Cody's. In 1977, Congress began reviewing numerous cases; it reinstated the medals for Cody and four other civilian scouts on June 12, 1989.[52][53]

- Cody was honored by two U.S. postage stamps.[16] One was a 15¢ Great Americans series postage stamp.

- The Buffalo Bill Historical Center was founded in Cody, Wyoming.

- Buffalo Bill's Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians is a collaborative project of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of History, with the assistance from the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. This digital history project contains letters, official programs, newspaper reports, posters, and photographs. The project highlights the social and cultural forces that shaped how American Indians were defined, debated, contested, and controlled in this period. This project was based on the Papers of William F. Cody project of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center.[54]

- The National Museum of American History's Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian Institution preserves and displays Gertrude Käsebier's photographs of the Wild West shows. Michelle Delaney has published Buffalo Bill's Wild West Warriors: Photographs by Gertrude Käsebier.[55]

- Some Oglala Lakota people carry on family show business traditions from ancestors who were Carlisle Indian School alumni and worked for Buffalo Bill and other Wild West shows.[56] Several national projects celebrate Wild Westers and Wild Westing. Wild Westers still perform in movies, powwows, pageants and rodeos.

- The Buffalo Bills, an NFL team based in Buffalo, New York, were named after the entertainer. Other early football teams (such as the Buffalo Bills of the AAFC) used the nickname, solely for name recognition, as Bill Cody had no special connection with the New York State city.

Representation in other media

Buffalo Bill has been portrayed in many literary, musical, and theatrical works, movies, and television shows, especially during the 1950s and 1960s, when Westerns were most popular. For example:

Film

- With Buffalo Bill on the U. P. Trail, 1926, a silent film starring Roy Stewart.

- 1944 film, Buffalo Bill starring Joel McCrea and Maureen O'Hara, a Hollywood account of Cody's life.

- Pony Express, 1953, an entirely fictional account of the creation of the Pony Express with Charlton Heston cast as Buffalo Bill.

- Robert Altman's feature film, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson (1976) portrays Cody and his Wild West show.

- The 2004 film Hidalgo, starring Viggo Mortensen as Frank Hopkins, features Buffalo Bill Cody as portrayed by J. K. Simmons as well as Annie Oakley (Elizabeth Berridge), a famed sharpshooter who was a star featured in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show.

Literature

- E. E. Cummings uses Buffalo Bill as an image of life and vibrancy in a poem, commonly known by its first two lines: "Buffalo Bill's / defunct". In Poetry, edited by J. Hunter, it is titled "portrait". (See insert.)

- Fantasy author Mercedes Lackey uses Cody as a character in her novel From a High Tower, in her Elemental Masters series.

- Dr. Seuss used Cody's nickname "Buffalo Bill" as one of twenty-three silly alternative names for one of Mrs. McCave's sons, all named "Dave" in the short story "Too Many Daves", from The Sneetches and Other Stories.

Music

- The art cover for Tyler, The Creator's album Goblin (2011) features a picture of Buffalo Bill at the age of 19.[57]

Musicals and theater

- He is featured as a character in the Broadway musical Annie Get Your Gun.

Sports

- The NFL football team the Buffalo Bills is named after him.

Television

- Cody was featured as a historical character on such television series about the West as Bat Masterson and Bonanza. His persona has been portrayed as that of an elder statesman or a flamboyant, self-serving exhibitionist.

- In 1959, the actor Britt Lomond played Cody in the episode "A Legend of Buffalo Bill" (1959) of the ABC/Warner Brothers western television series, Colt .45.[58]

Congo youth culture

Movies about Cody also inspired a youth subculture in the 1950s Belgian Congo, with young men and women dressing like this character and forming neighborhood gangs. After independence some of the "Bills" went on to careers in the music industry. [59]

See also

- Buffalo Bill Cody Homestead

- List of Medal of Honor recipients for the Indian Wars

- Ned Buntline: Contemporary of Buffalo Bill and author of successful dime novel series "Buffalo Bill Cody – King of the Border Men"

- William "Doc" Carver

- Pony Express

- Show Indians

- Wild Westing

References

- 1 2 "Scott County Conservation Department". Scottcountyiowa.com. Retrieved 2013-03-03.

- ↑ The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill by Don Russell

- ↑ "Historical Plaques of Peel Region".

- ↑ Cody, William F. The Life of HON. William F. Cody Known as Buffalo Bill, the Famous Hunter, Scout and Guide. A Public Domain Book.

- 1 2 3 Carter, Robert A. (2002). Buffalo Bill Cody: The Man Behind the Legend. Wiley. p. 512. ISBN 978-0-471-07780-0.

- ↑ "NO. 619: HOLCOMB VALLEY", State Historical Landmarks, San Bernardino County

- 1 2 3 Cody, Col. William F: The Adventures of Buffalo Bill Cody, 1st ed. page viii. New York and London: Harper & Brother, 1904

- ↑ Rochester History Alive: Some notable people who are buried in Mt. Hope Cemetery. Retrieved 2012-11-11

- 1 2 3 PBS (2001). "William F. Cody". New Perspectives on the West. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ Miles from Nowhere: Tales from America's Contemporary Frontier, Dayton Duncan, U of Nebraska Press, 2000 ISBN 0-8032-6627-8, ISBN 978-0-8032-6627-8

- 1 2 3 4 5 "William "Buffalo Bill" Cody". World Digital Library. 1907. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ↑ See Crossen, Forest. "Western Yesterdays, Volume VI: Thomas Fitzpatrick, Railroadman." (1968, Paddock Publishing). Fitzpatrick, a lifelong friend of Cody, met him when he was hired to shoot buffalo to feed the work crew building the Kansas Pacific Railroad.

- ↑ Herring, Hal (2008). Famous Firearms of the Old West: From Wild Bill Hickok's Colt Revolvers to Geronimo's Winchester, Twelve Guns That Shaped Our History. TwoDot. p. 224. ISBN 0-7627-4508-8.

- ↑ Russell, Don (1982). The lives and legends of Buffalo Bill. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780806115375. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ Streeby, Shelley (2002). American sensations : class, empire, and the production of popular culture ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Berkeley [u.a.]: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0520229457. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wilson, R.L. (1998). Buffalo Bill's Wild West: An American Legend. Random House. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-375-50106-7.

- ↑ Performing the American Frontier, 1870–1906, Roger A. Hall, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p.54, ISBN 0-521-79320-3, ISBN 978-0-521-79320-9

- ↑ The life of Hon. William F. Cody, known as Buffalo Bill, the famous hunter, scout and guide. An autobiography, F. E. Bliss. Hartford, CT, 1879, p329

- ↑ "The Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave". Retrieved June 7, 2008

- ↑ "Buffalo Jones". h-net.msu.edu. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ↑ Louis S. Warren, "Cody's Last Stand: Masculine Anxiety, the Custer Myth, and the Frontier of Domesticity in Buffalo Bill's Wild West", in, The Western Historical Quarterly, Vol 34. No. 1 (Spring 2003) pp. 55 of 49–69

- ↑ "Could Building Site be burial ground of the lost warrior from Buffalo Bill's show?", Daily Mail, Retrieved on April 25, 2008

- ↑ Leonard, Teresa (January 9, 2014). "Annie Oakley injured in NC train disaster". News & Observer.

- ↑ Griffen, Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill, p. xviii.

- ↑ William F. Cody Archive

- ↑ Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, pp. 330–331.

- ↑ Gallop, Buffalo Bill's British Wild West, p. 129.

- ↑ Jonnes, Eiffel's Tower: And the World's Fair Where Buffalo Bill beguiled Paris, the Artists Quarreled, and Thomas Edison became a Count.

- ↑ Gallop, Buffalo Bill's British Wild West, p. 157.

- ↑ Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, p. 352.

- 1 2 "THE DEATH OF "EAGLE STAR" IN SHEFFIELD", Sheffield & Rotherham Independent, 26 August 1891, at American Tribes Forum, accessed 26 August 2014

- ↑ Griffen, Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill, p. xxi.

- ↑ Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, p. 439.

- ↑ Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933, p. 189.

- ↑ Kasson, Buffalo Bill's Wild West, p. 88.

- ↑ Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, p. 321.

- ↑ http://www.rootschat.com/forum/index.php?topic=296911.27

- ↑

- ↑ Kensel, W. Hudson. Pahaska Tepee, Buffalo Bill's Old Hunting Lodge and Hotel, A History, 1901–1946. Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 1987.

- ↑ "Buffalo Bill Dam History". Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ Staten Island on the Web: Famous Staten Islanders.

- 1 2 Don Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, 1979.

- ↑ Richard H. Montague, Memory Street, 1962.

- ↑ Russell, Don (1979). The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 469. ISBN 978-1-4343-4148-8.

- ↑ Weber, Francis J. (1979). America's Catholic heritage: some bicentennial reflections, 1776–1976. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin – Madison. p. 49.

- ↑ Mosesl, L.G. (1999). The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill. New Mexico: UNM Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-8263-2089-6.

- 1 2 "'Buffalo Bill' Cody". A Few Famous Freemasons: American Founders. Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon A.F. & A.M. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- 1 2 Lloyd, John & Mitchinson, John. The Book of General Ignorance. Faber & Faber, 2006.

- ↑ Colorado Transcript, May 17, 1917.

- ↑ Exhibit, National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, Fort Worth, Texas

- ↑ Goppert, Ennest J. "Buffalo Bill - Cody". Masonic World. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ↑ Polanski, Charles (2006). "The Medal's History". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ↑ Sterner, C. Douglas (1999–2009). "Restoration of 6 Awards Previously Purged From The Roll of Honor". HomeOfHeroes.com.

- ↑ Heppler, "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians", http://segonku.unl.edu/~jheppler/showindian/analysis/show-indians/standing-bear/ and the "Buffalo Bill Project"

- ↑ Buffalo Bill's Wild West Warriors: Photographs by Gertrude Käsebier

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.121.

- ↑ "Buffalo Bill at the age of 19". Anotha.com.

- ↑ "Colt .45". ctva.biz. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Page, Thomas (8 December 2015). "The Kinshasa cowboys: How Buffalo Bill started a subculture in Congo". CNN. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

Bibliography

- Cody, William F. (1879) The Life of Hon. William F. Cody Known as Buffalo Bill the Famous Hunter, Scout and Guide: An Autobiography, Hartford, CT: Frank E. Bliss. (A 1983 leather-bound facsimile edition was published by Time-Life Books, Inc. as part of their 31-volume "Classics of the Old West series).

- Cunningham, Tom F. (2007) Your Fathers Ghosts: Buffalo Bill's Wild West in Scotland, Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing, ISBN 1-84502-117-7

- Gallop, Alan (2001) Buffalo Bill's British Wild West, Stroud: Sutton, ISBN 0-7509-2702-X

- Griffin, Charles Eldridge (2010) Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-3465-1

- Jonnes, Jill (2010) Eiffel's Tower: And the World's Fair where Buffalo Bill Beguiled Paris, the Artists Quarreled, and Thomas Edison Became a Count, New York: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-311729-7

- Kasson, Joy S. (2000) Buffalo Bill's Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History, New York: Hill and Wang, ISBN 0-8090-3244-9

- Moses, L.G. (1996) Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883–1933, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 0-8263-2089-9

- Rosa, Joseph G. and May, Robin (1989) Buffalo Bill and His Wild West: A Pictorial Biography, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas,ISBN 0-7006-0398-0

- Russell, Don (1960) The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-1537-8

- Rydell, Robert W.; Kroes, Rob (2005) Buffalo Bill in Bologna: The Americanization of the World, 1869–1922 Chicago:University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-73242-8

- Sell, Henry Blackman and Weybright, Victor (1955) Buffalo Bill and the Wild West, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wetmore, Helen Cody (1899) Last of the Great Scouts: The Life Story of Col. William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill), as told by His Sister Helen Cody Wetmore, Duluth, Minnesota: The Duluth Press Printing Co.

- Wilson, R.L. and Martin, Greg (1998) Buffalo Bill's Wild West: An American Legend, New York:Random House ISBN 0-375-50106-1

Further reading

- Buffalo Bill Days (June 22–24, 2007). A 20-page special section of The Sheridan Press, published in June 2007 by Sheridan Newspapers, Inc., 144 Grinnell Avenue, Post Office Box 2006, Sheridan, Wyoming, 82801, USA. (Includes extensive information about Buffalo Bill, as well as the schedule of the annual three-day event held in Sheridan, Wyoming.)

- Story of the Wild West and Camp-Fire Chats by Buffalo Bill (Hon. W.F. Cody.) "A Full and Complete History of the Renowned Pioneer Quartette, Boone, Crockett, Carson and Buffalo Bill.", c1888 by HS Smith, published 1889 by Standard Publishing Co., Philadelphia, PA.

- The life of Hon. William F. Cody, known as Buffalo Bill, the famous hunter, scout and guide. An autobiography, F. E. Bliss. Hartford, Conn, 1879 Digitized from the Library of Congress.

- "Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory and Popular History", by Joy S. Kasson, published by Hill & Wang publishing co., 2001

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buffalo Bill. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Buffalo Bill. |

- Cody Studies with digital research modules and historiography

- "The Papers of William F. Cody". Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- William F. Cody Archive

- "Buffalo Bill Center of the West". Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- Works by Buffalo Bill at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Buffalo Bill at Internet Archive

- Works by Buffalo Bill at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Hidden Horsham – Buffalo Bill's Wild West". Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- Illinois State University, Milner Library, Special Collections, Circus and Allied Arts Collection's "Buffalo Bill Letters". Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- Heppler, Jason. "The Wild West Show and the Progressive Image of American Indians". University of Nebraska–Lincoln and Buffalo Bill Historical Center. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|