Indonesia

Coordinates: 5°S 120°E / 5°S 120°E

| Republic of Indonesia Republik Indonesia |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Bhinneka Tunggal Ika" (Old Javanese) "Unity in Diversity" National ideology: Pañcasīla[1][2] |

||||||

| Anthem: Indonesia Raya Great Indonesia |

||||||

![Location of Indonesia (green)in ASEAN (dark grey) – [Legend]](../I/m/Location_Indonesia_ASEAN.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Jakarta 6°10.5′S 106°49.7′E / 6.1750°S 106.8283°E | |||||

| Official languages | Indonesian | |||||

| Religion | Officially recognised:[a] Islam Protestantism Catholicism Hinduism Buddhism Confucianism |

|||||

| Demonym | Indonesian | |||||

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic | |||||

| • | President | Joko Widodo | ||||

| • | Vice-President | Jusuf Kalla | ||||

| Legislature | People's Consultative Assembly | |||||

| • | Upper house | Regional Representative Council | ||||

| • | Lower house | People's Representative Council | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

| • | Dutch East India Company | 20 March 1602 | ||||

| • | Netherlands Indies | 1 January 1800 | ||||

| • | Japanese occupation | 9 March 1942 | ||||

| • | Declared Independence | 17 August 1945 | ||||

| • | United States of Indonesia | 27 December 1949 | ||||

| • | Federation dissolved | 17 August 1950 | ||||

| • | New Order | 12 March 1967 | ||||

| • | Reformasi | 21 May 1998 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Land | 1,904,569 km2 (15th) 735,358 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 4.85 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2015 estimate | 255,461,700[3] | ||||

| • | 2010 census | 237,424,363[4] (4th) | ||||

| • | Density | 124.66/km2 (84th) 322.87/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $2.840 trillion[4] (8th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $11,135[4] (102nd) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $895.677 billion[4] (16th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $3,511[4] (117th) | ||||

| Gini (2010) | 35.6[5] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | medium · 110th |

|||||

| Currency | Indonesian rupiah (Rp) (IDR) | |||||

| Time zone | various (UTC+7 to +9) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | various (UTC+7 to +9) | ||||

| Date format | DD/MM/YYYY | |||||

| Drives on the | left | |||||

| Calling code | +62 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | ID | |||||

| Internet TLD | .id | |||||

| a. | ^a The government officially recognises only six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.[7] | |||||

Indonesia (![]() i/ˌɪndəˈniːʒə/ IN-də-NEE-zhə or /ˌɪndoʊˈniːziə/ IN-doh-NEE-zee-ə; Indonesian: [ɪndonesia]), officially the Republic of Indonesia (Indonesian: Republik Indonesia [rɛpublik ɪndonesia]), is a sovereign island country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. It is the largest island country in the world by the number of islands, with more than fourteen thousand islands.[8] Indonesia has an estimated population of over 255 million people and is the world's fourth most populous country and the most populous Muslim-majority country. The world's most populous island of Java contains more than half of the country's population.

i/ˌɪndəˈniːʒə/ IN-də-NEE-zhə or /ˌɪndoʊˈniːziə/ IN-doh-NEE-zee-ə; Indonesian: [ɪndonesia]), officially the Republic of Indonesia (Indonesian: Republik Indonesia [rɛpublik ɪndonesia]), is a sovereign island country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. It is the largest island country in the world by the number of islands, with more than fourteen thousand islands.[8] Indonesia has an estimated population of over 255 million people and is the world's fourth most populous country and the most populous Muslim-majority country. The world's most populous island of Java contains more than half of the country's population.

Indonesia's republican form of government includes an elected legislature and president. Indonesia has 34 provinces, of which five have Special Administrative status. Its capital city is Jakarta. The country shares land borders with Papua New Guinea, East Timor, and the Malaysian Borneo. Other neighbouring countries include Singapore, the Philippines, Australia, Palau, and the Indian territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Indonesia is a founding member of ASEAN and a member of the G-20 major economies. The Indonesian economy is the world's 16th largest by nominal GDP and the 8th largest by GDP at PPP.

The Indonesian archipelago has been an important trade region since at least the 7th century, when Srivijaya and then later Majapahit traded with China and India. Local rulers gradually absorbed foreign cultural, religious and political models from the early centuries CE, and Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms flourished. Indonesian history has been influenced by foreign powers drawn to its natural resources. Muslim traders and Sufi scholars brought the now-dominant Islam,[9][10] while European powers brought Christianity and fought one another to monopolise trade in the Spice Islands of Maluku during the Age of Discovery. Following three and a half centuries of Dutch colonialism starting from the East Indonesia of West Papua, Timor to eventually all of West Indonesia, at times interrupted by Portuguese, French and British rule, Indonesia secured its independence after World War II. Indonesia's history has since been turbulent, with challenges posed by natural disasters, mass slaughter, corruption, separatism, a democratisation process, and periods of rapid economic change.

Indonesia consists of hundreds of distinct native ethnic and linguistic groups. The largest – and politically dominant – ethnic group are the Javanese. A shared identity has developed, defined by a national language, ethnic diversity, religious pluralism within a Muslim-majority population, and a history of colonialism and rebellion against it. Indonesia's national motto, "Bhinneka Tunggal Ika" ("Unity in Diversity" literally, "many, yet one"), articulates the diversity that shapes the country. Despite its large population and densely populated regions, Indonesia has vast areas of wilderness that support the world's second highest level of biodiversity. The country has abundant natural resources, yet poverty remains widespread.[11][12]

Etymology

The name Indonesia derives from the Greek words Indós and nèsos, meaning "Indian island".[13] The name dates to the 18th century, far predating the formation of independent Indonesia.[14] In 1850, George Windsor Earl, an English ethnologist, proposed the terms Indunesians—and, his preference, Malayunesians—for the inhabitants of the "Indian Archipelago or Malayan Archipelago".[15] In the same publication, a student of Earl's, James Richardson Logan, used Indonesia as a synonym for Indian Archipelago.[16][17] However, Dutch academics writing in East Indies publications were reluctant to use Indonesia. Instead, they used the terms Malay Archipelago (Maleische Archipel); the Netherlands East Indies (Nederlandsch Oost Indië), popularly Indië; the East (de Oost); and Insulinde.[18]

After 1900, the name Indonesia became more common in academic circles outside the Netherlands, and Indonesian nationalist groups adopted it for political expression.[18] Adolf Bastian, of the University of Berlin, popularised the name through his book Indonesien oder die Inseln des Malayischen Archipels, 1884–1894. The first Indonesian scholar to use the name was Suwardi Suryaningrat (Ki Hajar Dewantara), when he established a press bureau in the Netherlands with the name Indonesisch Pers-bureau in 1913.[14]

History

Pre-historical era

Fossils and the remains of tools show that the Indonesian archipelago was inhabited by Homo erectus, popularly known as "Java Man", between 1.5 million years ago and 35,000 years ago.[20][21][22] Homo sapiens reached the region by around 45,000 years ago.[23]

Austronesian peoples, who form the majority of the modern population, migrated to Southeast Asia from Taiwan. They arrived in Indonesia around 2000 BCE, and as they spread through the archipelago, confined the indigenous Melanesian peoples to the far eastern regions.[24] Ideal agricultural conditions, and the mastering of wet-field rice cultivation as early as the 8th century BCE,[25] allowed villages, towns, and small kingdoms to flourish by the 1st century CE. Indonesia's strategic sea-lane position fostered inter-island and international trade, including links with Indian kingdoms and China, which were established several centuries BCE.[26] Trade has since fundamentally shaped Indonesian history.[27][28]

Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms era

From the 7th century CE, the powerful Srivijaya naval kingdom flourished as a result of trade and the influences of Hinduism and Buddhism that were imported with it.[29] Between the eighth and 10th centuries CE, the agricultural Buddhist Sailendra and Hindu Mataram dynasties thrived and declined in inland Java, leaving grand religious monuments such as Sailendra's Borobudur and Mataram's Prambanan. The Hindu Majapahit kingdom was founded in eastern Java in the late 13th century, and under Gajah Mada, its influence stretched over much of Indonesia.[30]

The Spread of Islam

Although Muslim traders first traveled through Southeast Asia early in the Islamic era, the earliest evidence of Islamized populations in Indonesia dates to the 13th century in northern Sumatra.[31] Other Indonesian areas gradually adopted Islam, and it was the dominant religion in Java and Sumatra by the end of the 16th century. For the most part, Islam overlaid and mixed with existing cultural and religious influences, which shaped the predominant form of Islam in Indonesia, particularly in Java.[32] The first regular contact between Europeans and the peoples of Indonesia began in 1512, when Portuguese traders, led by Francisco Serrão, sought to monopolize the sources of nutmeg, cloves, and cubeb pepper in Maluku.[33] Dutch and British traders followed. In 1602, the Dutch established the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and became the dominant European power. Following bankruptcy, the VOC was formally dissolved in 1800, and the government of the Netherlands established the Dutch East Indies as a nationalized colony.[34]

European colonisation

Following bankruptcy, the VOC was formally dissolved in 1800, and the government of the Netherlands established the Dutch East Indies as a nationalised colony.[35] For most of the colonial period, Dutch control over the archipelago was tenuous outside of coastal strongholds; only in the early 20th century did Dutch dominance extend to what was to become Indonesia's current boundaries.[36] Despite major internal political, social and sectarian divisions during the National Revolution, Indonesians, on the whole, found unity in their fight for independence. Japanese occupation during World War II ended Dutch rule,[37] and encouraged the previously suppressed Indonesian independence movement.[38] A later UN report stated that four million people died in Indonesia as a result of famine and forced labor during the Japanese occupation.[39] Two days after the surrender of Japan in August 1945, Sukarno, an influential nationalist leader, declared independence and was appointed president.[40] The Netherlands tried to reestablish their rule, and an armed and diplomatic struggle ended in December 1949, when in the face of international pressure, the Dutch formally recognized Indonesian independence[41] (with the exception of the Dutch territory of West New Guinea, which was incorporated into Indonesia following the 1962 New York Agreement, and the UN-mandated Act of Free Choice of 1969).[42]

New Order and Reformasi

Sukarno moved Indonesia from democracy towards authoritarianism, and maintained his power base by balancing the opposing forces of the military and the PKI.[43] An attempted coup on 30 September 1965 was countered by the army, who led a violent anti-communist purge, during which the PKI was blamed for the coup and effectively destroyed.[44][45][46] Hundreds of thousands of people are estimated to have been killed.[47][48] The head of the military, General Suharto, outmaneuvered the politically weakened Sukarno and was formally appointed president in March 1968. His New Order administration[49] was supported by the US government,[50][51][52] and encouraged foreign direct investment in Indonesia, which was a major factor in the subsequent three decades of substantial economic growth. However, the authoritarian "New Order" was widely accused of corruption and suppression of political opposition.[53][54][55]

Indonesia was the country hardest hit by the late 1990s Asian financial crisis.[56] This increased popular discontent with the New Order and led to popular protest across the country. Suharto resigned on 21 May 1998.[57] In 1999, East Timor voted to secede from Indonesia, after a twenty-five-year military occupation that was marked by international condemnation of repression of the East Timorese.[58] Since Suharto's resignation, a strengthening of democratic processes has included a regional autonomy program, and the first direct presidential election in 2004, which was won by Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who went on to win a second term in 2009. Political and economic instability, social unrest, corruption, and terrorism slowed progress; however, in the last five years the economy has performed strongly. Although relations among different religious and ethnic groups are largely harmonious, sectarian discontent and violence have persisted.[59] A political settlement to an armed separatist conflict in Aceh was achieved in 2005.[60] Joko Widodo was elected as President in the 2014 presidential election.

Government and politics

Indonesia is a republic with a presidential system. As a unitary state, power is concentrated in the central government. Following the resignation of President Suharto in 1998, Indonesian political and governmental structures have undergone major reforms. Four amendments to the 1945 Constitution of Indonesia[61] have revamped the executive, judicial, and legislative branches.[62] The president of Indonesia is the head of state and head of government, commander-in-chief of the Indonesian National Armed Forces, and the director of domestic governance, policy-making, and foreign affairs. The president appoints a council of ministers, who are not required to be elected members of the legislature. The 2004 presidential election was the first in which the people directly elected the president and vice-president.[63] The president may serve a maximum of two consecutive five-year terms.[64]

The highest representative body at national level is Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat (People's Consultative Assembly) or MPR. Its main functions are supporting and amending the constitution, inaugurating the president, and formalising broad outlines of state policy. It has the power to impeach the president.[65] The MPR comprises two houses; Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (People's Representative Council) or DPR, with 560 members, and Dewan Perwakilan Daerah (Regional Representative Council) or DPD, with 132 members.[66] The DPR passes legislation and monitors the executive branch; party-aligned members are elected for five-year terms by proportional representation.[62] Reforms since 1998 have markedly increased the DPR's role in national governance.[67] The DPD is a new chamber for matters of regional management.[68]

Most civil disputes appear before Pengadilan Negeri (State Court); appeals are heard before Pengadilan Tinggi (High Court). Mahkamah Agung is the country's highest court, and hears final cessation appeals and conducts case reviews. Other courts include the Commercial Court, which handles bankruptcy and insolvency; Pengadilan Tata Negara (State Administrative Court) to hear administrative law cases against the government; Mahkamah Konstitusi (Constitutional Court) to hear disputes concerning legality of law, general elections, dissolution of political parties, and the scope of authority of state institutions; and Pengadilan Agama (Religious Court) to deal with codified Sharia Law cases.[69]

Foreign relations and military

In contrast to Sukarno's anti-imperialistic antipathy to Western powers and tensions with Malaysia, Indonesia's foreign relations since the New Order era have been based on economic and political co-operation with the Western world.[71] Indonesia maintains close relationships with its neighbours in Asia, and is a founding member of ASEAN and the East Asia Summit.[66] The country restored relations with the People's Republic of China in 1990 following a freeze in place since anti-communist purges early in the Suharto era.[69] Indonesia has been a member of the United Nations since 1950,[72] and was a founder of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC).[66] Indonesia is signatory to the ASEAN Free Trade Area agreement, the Cairns Group, and the World Trade Organization (WTO), and a member of OPEC. Indonesia has received humanitarian and development aid since 1966, in particular from the United States, western Europe, Australia, and Japan.[66]

The Indonesian government has worked with other countries to apprehend and prosecute perpetrators of major bombings linked to militant Islamism and Al-Qaeda.[73] The deadliest bombing killed 202 people (including 164 international tourists) in the Bali resort town of Kuta in 2002.[74] The attacks, and subsequent travel warnings issued by other countries, severely damaged Indonesia's tourism industry and foreign investment prospects.[75]

Indonesia's armed forces (TNI) include the army (TNI–AD), navy (TNI–AL, which includes marines), and air force (TNI–AU).[76] The army has about 400,000 active-duty personnel. Defense spending in the national budget was 4% of GDP in 2006, and is controversially supplemented by revenue from military commercial interests and foundations.[77] One of the reforms following the 1998 resignation of Suharto was the removal of formal TNI representation in parliament; nevertheless, its political influence remains extensive.[78]

Separatist movements in the provinces of Aceh and Papua have led to armed conflict, and subsequent allegations of human rights abuses and brutality from all sides.[79][80] Following a sporadic thirty-year guerrilla war between the Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (GAM) and the Indonesian military, a ceasefire agreement was reached in 2005.[81] In Papua, there has been a significant, albeit imperfect, implementation of regional autonomy laws, and a reported decline in the levels of violence and human rights abuses, since the presidency of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.[82]

Administrative divisions

Administratively, Indonesia consists of 34 provinces, five of which have special status. Each province has its own legislature and governor. The provinces are subdivided into regencies (kabupaten) and cities (kota), which are further subdivided into districts (kecamatan or distrik in Papua and West Papua), and again into administrative villages (either desa, kelurahan, kampung, nagari in West Sumatra, or gampong in Aceh). Village is the lowest level of government administration in Indonesia. Furthermore, a village is divided into several community groups (rukun warga (RW)) which are further divided into neighbourhood groups (rukun tetangga (RT)). In Java the desa (village) is divided further into smaller units called dusun or dukuh (hamlets), these units are the same as rukun warga. Following the implementation of regional autonomy measures in 2001, the regencies and cities have become the key administrative units, responsible for providing most government services. The village administration level is the most influential on a citizen's daily life and handles matters of a village or neighbourhood through an elected lurah or kepala desa (village chief).

The provinces of Aceh, Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Papua, and West Papua have greater legislative privileges and a higher degree of autonomy from the central government than the other provinces. The Acehnese government, for example, has the right to create certain elements of an independent legal system; in 2003, it instituted a form of sharia (Islamic law).[83] Yogyakarta was granted the status of Special Region in recognition of its pivotal role in supporting Indonesian Republicans during the Indonesian Revolution and its willingness to join Indonesia as a republic.[84] Papua, formerly known as Irian Jaya, was granted special autonomy status in 2001 and was split into Papua and West Papua in February 2003.[85][86] Jakarta is the country's special capital region.

- Indonesian provinces and their capitals, listed by region

Indonesian name is in parentheses if different from English.

* indicates provinces with special status

Geography

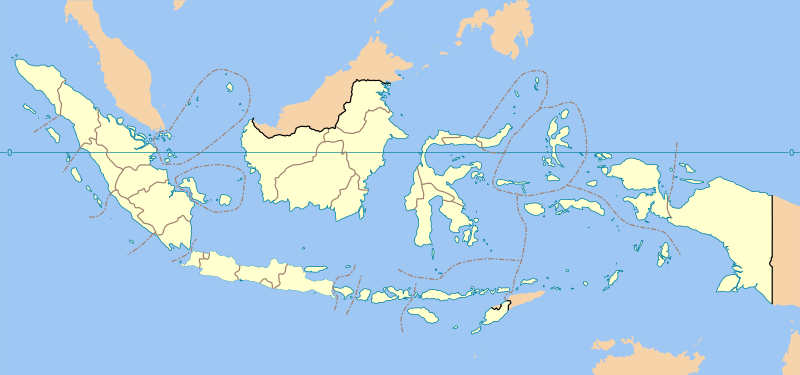

Indonesia lies between latitudes 11°S and 6°N, and longitudes 95°E and 141°E. It consists of 17,508 islands, about 6,000 of which are inhabited.[87] These are scattered over both sides of the equator. The largest are Java, Sumatra, Borneo (shared with Brunei and Malaysia), New Guinea (shared with Papua New Guinea), and Sulawesi. Indonesia shares land borders with Malaysia on Borneo, Papua New Guinea on the island of New Guinea, and East Timor on the island of Timor. Indonesia shares maritime borders across narrow straits with Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Palau to the north, and with Australia to the south. The capital, Jakarta, is on Java and is the nation's largest city, followed by Surabaya, Bandung, Medan, and Semarang.[88]

At 1,919,440 square kilometres (741,050 sq mi), Indonesia is the world's 15th-largest country in terms of land area and world's 7th-largest country in terms of combined sea and land area.[89] Its average population density is 134 people per square kilometre (347 per sq mi), 79th in the world,[90] although Java, the world's most populous island,[91] has a population density of 940 people per square kilometre (2,435 per sq mi). At 4,884 metres (16,024 ft), Puncak Jaya in Papua is Indonesia's highest peak, and Lake Toba in Sumatra its largest lake, with an area of 1,145 square kilometres (442 sq mi). The country's largest rivers are in Kalimantan, and include the Mahakam and Barito; such rivers are communication and transport links between the island's river settlements.[92]

Indonesia's location on the edges of the Pacific, Eurasian, and Australian tectonic plates makes it the site of numerous volcanoes and frequent earthquakes. Indonesia has at least 150 active volcanoes,[93] including Krakatoa and Tambora, both famous for their devastating eruptions in the 19th century. The eruption of the Toba supervolcano, approximately 70,000 years ago, was one of the largest eruptions ever, and a global catastrophe. Recent disasters due to seismic activity include the 2004 tsunami that killed an estimated 167,736 in northern Sumatra,[94] and the Yogyakarta earthquake in 2006. However, volcanic ash is a major contributor to the high agricultural fertility that has historically sustained the high population densities of Java and Bali.[95]

Lying along the equator, Indonesia has a tropical climate, with two distinct monsoonal wet and dry seasons. Average annual rainfall in the lowlands varies from 1,780–3,175 millimetres (70.1–125.0 inches), and up to 6,100 millimetres (240 inches) in mountainous regions. Mountainous areas – particularly in the west coast of Sumatra, West Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua – receive the highest rainfall. Humidity is generally high, averaging about 80%. Temperatures vary little throughout the year; the average daily temperature range of Jakarta is 26–30 °C (79–86 °F).[96]

Biodiversity

Indonesia's size, tropical climate, and archipelagic geography, support the world's second highest level of biodiversity after Brazil.[97] Its flora and fauna is a mixture of Asian and Australasian species.[98] The islands of the Sunda Shelf (Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and Bali) were once linked to the Asian mainland, and have a wealth of Asian fauna. Large species such as the tiger, rhinoceros, orangutan, elephant, and leopard, were once abundant as far east as Bali, but numbers and distribution have dwindled drastically. Forests cover approximately 60% of the country.[99] In Sumatra and Kalimantan, these are predominantly of Asian species. However, the forests of the smaller, and more densely populated Java, have largely been removed for human habitation and agriculture. Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara, and Maluku – having been long separated from the continental landmasses—have developed their own unique flora and fauna.[100] Papua was part of the Australian landmass, and is home to a unique fauna and flora closely related to that of Australia, including over 600 bird species.[101]

Indonesia is second only to Australia in terms of total endemic species, with 36% of its 1,531 species of bird and 39% of its 515 species of mammal being endemic.[102] Indonesia's 80,000 kilometres (50,000 miles) of coastline are surrounded by tropical seas that contribute to the country's high level of biodiversity. Indonesia has a range of sea and coastal ecosystems, including beaches, sand dunes, estuaries, mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass beds, coastal mudflats, tidal flats, algal beds, and small island ecosystems.[13] Indonesia is one of Coral Triangle countries with the world's greatest diversity of coral reef fish with more than 1,650 species in eastern Indonesia only.[103] The British naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, described a dividing line between the distribution of Indonesia's Asian and Australasian species.[104] Known as the Wallace Line, it runs roughly north–south along the edge of the Sunda Shelf, between Kalimantan and Sulawesi, and along the deep Lombok Strait, between Lombok and Bali. West of the line the flora and fauna are more Asian; moving east from Lombok, they are increasingly Australian. In his 1869 book, The Malay Archipelago, Wallace described numerous species unique to the area.[105] The region of islands between his line and New Guinea is now termed Wallacea.[104]

Environment

Indonesia's high population and rapid industrialisation present serious environmental issues, which are often given a lower priority due to high poverty levels and weak, under-resourced governance.[106] Issues include large-scale deforestation (much of it illegal) and related wildfires causing heavy smog over parts of western Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore; over-exploitation of marine resources; and environmental problems associated with rapid urbanisation and economic development, including air pollution, traffic congestion, garbage management, and reliable water and waste water services.[106] Deforestation and the destruction of peatlands make Indonesia the world's third largest emitter of greenhouse gases.[107] Habitat destruction threatens the survival of indigenous and endemic species, including 140 species of mammals identified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as threatened, and 15 identified as critically endangered, including the Bali starling,[108] Sumatran orangutan,[109] and Javan rhinoceros.[110] Much of Indonesia's deforestation is caused by forest clearing for the palm oil industry, which has cleared 18 million hectares of forest for palm oil expansion. Palm oil expansion requires land reallocation as well as changes to the local and natural ecosystems. Palm oil expansion can generate wealth for local communities, but it can also degrade ecosystems and cause social problems.[111]

Economy

Indonesia has a mixed economy in which both the private sector and government play significant roles.[112] The country is the largest economy in Southeast Asia and a member of the G-20 major economies.[113] Indonesia's estimated gross domestic product (nominal), as of 2014, was US$887 billion while GDP in PPP terms is US$2.685 trillion. It is the sixteenth largest economy in the world by nominal GDP and is the eighth largest in terms of GDP (PPP). As of 2014, per capita GDP in PPP was US$10,651 (international dollars) while Nominal per capita GDP was US$3,518.[114][115] The debt ratio to the GDP is 26%.[116][117][118] The industry sector is the economy's largest and accounts for 46.4% of GDP (2012), this is followed by services (38.6%) and agriculture (14.4%). However, since 2012, the service sector has employed more people than other sectors, accounting for 47.9% of the total labour force, this has been followed by agriculture (38.9%) and industry (13.2%).[119] Agriculture, however, had been the country's largest employer for centuries.[120][121]

According to WTO data, Indonesia was the 27th biggest exporting country in the world in 2010, moving up three places from the previous year.[122] Indonesia's main export markets (2009) are Japan (17.28%), Singapore (11.29%), the United States (10.81%), and China (7.62%). The major suppliers of imports to Indonesia are Singapore (24.96%), China (12.52%), and Japan (8.92%). In 2014, Indonesia ran a trade deficit with export revenues of US$176 billion and import expenditure of US$178.2 billion.[123] The country has extensive natural resources, including crude oil, natural gas, tin, copper, and gold. Indonesia's major imports include machinery and equipment, chemicals, fuels, and foodstuffs, and the country's major export commodities include oil and gas, electrical appliances, plywood, rubber, and textiles.[87] In an attempt to boost the domestic mineral processing industry and encourage exports of higher value-added mineral products, the Indonesian government implemented a ban on exports of unprocessed mineral ores in 2014.[123] Palm oil production is important to the economy of Indonesia as the country is the world's biggest producer and consumer of the commodity, providing about half the world supply.[124] Oil palm plantations stretch across 6 million hectares (roughly twice the size of Belgium). The country plans by 2015 to add 4 million additional hectares towards oil palm biofuel production.[125] As of 2012, Indonesia produces 35 percent of the world's certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO).[126]

The tourism sector contributes to around US$10.1 billion of foreign exchange in 2013, and ranked as the 4th largest among goods and services export sectors.[127] Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, China and Japan are the top five source of visitors to Indonesia.

In the 1960s, the economy deteriorated drastically as a result of political instability, a young and inexperienced government, and economic nationalism, which resulted in severe poverty and hunger. By the time of President Sukarno's downfall in the mid-1960s, the economy was in chaos with 1,000% annual inflation, shrinking export revenues, crumbling infrastructure, factories operating at minimal capacity, and negligible investment. After Sukarno's downfall, the New Order administration brought a degree of discipline to economic policy that quickly brought inflation down, stabilised the currency, rescheduled external debt, and attracted foreign aid and investment. (See Berkeley Mafia). Indonesia is currently Southeast Asia's only member of OPEC, and the 1970s oil price raises provided an export revenue windfall that contributed to sustained high economic growth rates, averaging over 7% from 1968 to 1981.[128] Following further reforms in the late 1980s,[129] foreign investment flowed into Indonesia, particularly into the rapidly developing export-oriented manufacturing sector, and from 1989 to 1997, the Indonesian economy grew by an average of over 7%.[130][131]

Indonesia was the country hardest hit by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. During the crisis, there were sudden and large capital outflows leading the rupiah to go into free fall. Against the US dollar the rupiah dropped from about Rp 2,600 in late 1997 to a low point of around Rp 17,000 some months later and the economy shrank by a remarkable 13.7%. These developments led to widespread economic distress across the economy and contributed to the political crisis of 1998 which saw Suharto resign as president.[132] The rupiah later stabilised in the Rp. 8,000 range[133] and economic growth returned to 4% per year by 2000.[134] However, the currency still fluctuates, dropping below Rp 11,000 per dollar in September 2013. In addition, corruption has been a persistent problem. Transparency International, for example, has since ranked Indonesia below 100 in its Corruption Perceptions Index.[135][136] Since 2007, however, with the improvement in banking sector and domestic consumption, national economic growth has accelerated to over 6% annually[137][138][139] and this helped the country weather the 2008–2009 Great Recession.[140] The Indonesian economy performed strongly during the financial crisis of 2007–08 and in 2012, its GDP grew by over 6%.[141] The country regained its investment grade rating in late 2011 after losing it in 1997.[142] However, as of 2014, 11% of the population lived below the poverty line and the official open unemployment rate was 5.9%.[143]

Indonesia has a sizeable automotive industry, which produced almost 1.3 million motor vehicles in 2014, ranking as the 15th largest producer in the world.[144] Nowadays, Indonesian automotive companies are able to produce cars with high ratio of local content (80% - 90%).[145] With production peaking at 14.5 billion packs in 2011, Indonesia is the second largest producer of instant noodle after China which produces 42.5 billion packs a year.[146] Indofood is the largest instant noodle producer in the world. Indomie brand by Indofood is one of the Indonesia's best known global brand.[147]

Of the world's 500 largest companies measured by revenue in 2014, the Fortune Global 500, two are headquartered in Indonesia i.e. Pertamina and Perusahaan Listrik Negara.[148]

Transport

Road transport is predominant, with a total system length of 437,759 km in 2008. Many cities and towns have some form of transportation for hire available as well such as taxis. There are usually also bus services of various kinds such as the Kopaja buses and the more sophisticated TransJakarta bus rapid transit system in Jakarta. The TransJakarta is the largest bus rapid transit system in the world, boasts some 194 km and carriers more than 300,000 passengers daily.[149] In addition, BRT systems exist in Yogyakarta, Palembang, Bandung, Denpasar, Pekanbaru, Semarang, Makassar, and Padang without segregated lane. Many cities also have motorised auto rickshaws (bajaj) of various kinds. Cycle rickshaws, called becak in Indonesia, are a regular sight on city roads and provide inexpensive transportation.

The rail transport system has four unconnected networks in Java and Sumatra primarily dedicated to transport bulk commodities and long-distance passenger traffic. The inter-city rail network on Java is complemented by local commuter rail services in the Jakarta metropolitan area (KA Commuter Jabodetabek), Surabaya, Medan, and Bandung. In Jakarta, suburban rail services carry 550,000 passengers a day.[150] In addition, mass rapid transit and light rail transit systems are under construction in Jakarta.

Sea transport is extremely important for economic integration and for domestic and foreign trade. It is well developed, with each of the major islands having at least one significant port city. Because Indonesia encompasses a sprawling archipelago, maritime shipping provides essential links between different parts of the country. Boats in common use include large container ships, a variety of ferries, passenger ships, sailing ships, and smaller motorised vessels. Traditional wooden vessel pinisi still widely used as the inter-island freight service within Indonesian archipelago. Port of Tanjung Priok is Indonesia's busiest port, and the 21st busiest port in the world in 2013, handling over 6.59 million TEUs.[151] To boost the port capacity, two-phase "New Tanjung Priok" extension project is currently ongoing. When fully operational in 2023, it will triple existing annual capacity.

Frequent ferry services cross the straits between nearby islands, especially in the chain of islands stretching from Sumatra through Java to the Lesser Sunda Islands. On the busy crossings between Sumatra, Java, and Bali, multiple car ferries run frequently twenty-four hours per day. There are also international ferry services between across the Strait of Malacca between Sumatra and Malaysia, and between Singapore and nearby Indonesian islands, such as Batam. A network of passenger ships makes longer connections to more remote islands, especially in the eastern part of the archipelago. The national shipping line, Pelni, provides passenger service to ports throughout the country on a two to four week schedule. These ships generally provide the least expensive way to cover long distances between islands. Still smaller privately run boats provide service between islands.

As of 2014, there were 237 airports in Indonesia,[152] including 17 international airports. Soekarno–Hatta International Airport is the 18th busiest airport in the world, serving 12,314,667 passengers, according to Airports Council International.[153] Today the airport is running over capacity. After T3 Soekarno-Hatta Airport expansion will be finished in May 2016, the total capacity of three terminals become 43 million passengers a year. T1 and T2 also will be revitalised, so all the three terminals finally will accommodate 67 million passengers a year.[154] When finished, Soekarno-Hatta airport will be an aerotropolis.[155] Juanda Airport in Surabaya and Ngurah Rai in Bali are the country's 2nd and 3rd busiest airport.[156] Garuda Indonesia, flag carrier of Indonesia since 1949, was selected by Skytrax as "The World's Best Economy Class" in 2013. In December 2014, Garuda Indonesia was awarded as a "5-Star Airline" by Skytrax[157] as well as in June 2015, it was awarded with "The World's Best Cabin Crew".[158]

Science and technology

Living in an agrarian and maritime culture the people in Indonesian's archipelago have been famous in some traditional technologies, particularly in agriculture and marine. In agriculture, for instance, the people in Indonesia, and also in many other Southeast Asian countries, are famous in paddy cultivation technique namely terasering. Bugis and Makassar people in Indonesia are also well-known with their technology in making wooden sailing vessel called pinisi boat.[159]

In aerospace technology, Indonesia has a long history in developing military and small commuter aircraft as the only country in Southeast Asia to produce and develop its own aircraft, also producing aircraft components for Boeing and Airbus, with its state-owned aircraft company (founded in 1976), the Indonesian Aerospace (Indonesian: PT. Dirgantara Indonesia), which, with EADS CASA of Spain developed the CN-235 aircraft, which has been exported to many countries. B. J. Habibie, a former Indonesian president played an important role in this achievement. While active as a professor in Germany, Habibie conducted many research assignments, producing theories on thermodynamics, construction, and aerodynamics, known as the Habibie Factor, Habibie Theorem, and Habibie Method respectively.[160] Indonesia also hopes to manufacture the South Korean KAI KF-X fighter.[161]

Furthermore, Indonesia has a well established railway industry, with its state-owned train manufacturer company, the Indonesian Railway Industry (Indonesian: PT. Industri Kereta Api), located in Madiun, East Java. Since 1982, the company has been producing passenger train wagons, freight wagons and other railway technologies and exported to many countries, such as Malaysia and Bangladesh.[162] In the 1980s an Indonesian engineer, Tjokorda Raka Sukawati invented a road construction technique named Sosrobahu which becomes famous afterwards and widely used by many countries. The technology has been exported to the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore and in 1995, a patent was granted to Indonesia.[163]

Demographics

According to the 2010 national census, the population of Indonesia is 237.6 million, with high population growth at 1.9%.[164] 58% of the population lives in Java,[165] the world's most populous island.[91] In 1961, the first post-colonial census gave a total population of 97 million.[166] The population is expected to grow to around 269 million by 2020 and 321 million by 2050.[167] An additional 8 million Indonesian live overseas, comprising one of the world's largest diasporas. Most of them settled in Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Netherlands, United States, and Australia.[168]

Ethnicity

Indonesia is a very ethnically and linguistically diverse country, with around 300 distinct native ethnic groups, and 742 different languages and dialects.[169][170] Most Indonesians are descended from Austronesian-speaking peoples whose languages can be traced to Proto-Austronesian, which possibly originated in Taiwan. Another major grouping are the Melanesians, who inhabit eastern Indonesia.[24][88][171] The largest ethnic group is the Javanese, who comprise 42% of the population, and are politically and culturally dominant.[172] The Sundanese, ethnic Malays, and Madurese are the largest non-Javanese groups.[173] A sense of Indonesian nationhood exists alongside strong regional identities.[174] Social, religious and ethnic tensions have triggered horrendous violence.[175][176][177] Chinese Indonesians are an influential ethnic minority comprising 3–4% of the population.[178] Much of the country's privately owned commerce and wealth is Chinese-Indonesian-controlled.[179][180] Chinese businesses in Indonesia are part of the larger bamboo network, a network of overseas Chinese businesses operating in the markets of Southeast Asia that share common family and cultural ties.[181] This has contributed to considerable resentment, and even anti-Chinese violence.[182][183][184]

Religion

While religious freedom is stipulated in the Indonesian constitution,[186] the government officially recognises only six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.[7] Indonesia is the world's most populous Muslim-majority country, at 87.2% in 2010, with the majority being Sunni Muslims (99%).[187][188][189] The Shias and Ahmadis respectively constitute 0.5% and 0.2% of the Muslim population.[190]

In 2010, Christians made up almost 10% of the population (among them 7% were Protestant, 2.9% Roman Catholic), 1.7% were Hindu, and 0.9% were Buddhist or other. Most Indonesian Hindus are Balinese,[191] and most Buddhists in modern-day Indonesia are ethnic Chinese.[192] Though now minority religions, Hinduism and Buddhism remain defining influences in Indonesian culture. Islam was first adopted by Indonesians in northern Sumatra in the 13th century, through the influence of traders, and became the country's dominant religion by the 16th century.[193] Roman Catholicism was brought to Indonesia by early Portuguese colonialists and missionaries,[194][195] and the Protestant denominations are largely a result of Dutch Reformed and Lutheran missionary efforts during the country's colonial period.[196][197][198] A large proportion of Indonesians—such as the Javanese abangan, Balinese Hindus, and Dayak Christians—practice a less orthodox, syncretic form of their religion, which draws on local customs and beliefs.[199]

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Jakarta Surabaya |

1 | Jakarta | Jakarta | 9,588,198 | 11 | South Tangerang | Banten | 1,290,322 |  Bandung |

| 2 | Surabaya | East Java | 2,765,487 | 12 | Bogor | West Java | 950,334 | ||

| 3 | Bandung | West Java | 2,394,873 | 13 | Batam | Riau Islands | 944,285 | ||

| 4 | Bekasi | West Java | 2,334,871 | 14 | Pekanbaru | Riau | 897,767 | ||

| 5 | Medan | North Sumatra | 2,097,610 | 15 | Bandar Lampung | Lampung | 881,801 | ||

| 6 | Tangerang | Banten | 1,798,601 | 16 | Padang | West Sumatra | 833,562 | ||

| 7 | Depok | West Java | 1,738,570 | 17 | Malang | East Java | 820,243 | ||

| 8 | Semarang | Central Java | 1,555,984 | 18 | Denpasar | Bali | 788,589 | ||

| 9 | Palembang | South Sumatra | 1,455,284 | 19 | Samarinda | East Kalimantan | 727,500 | ||

| 10 | Makassar | South Sulawesi | 1,338,663 | 20 | Tasikmalaya | West Java | 635,464 | ||

Education

Education in Indonesia is compulsory for twelve years.[201][202] Parents can choose between state-run, non sectarian public schools supervised by Depdiknas (Department of National Education) or private or semi-private religious (usually Islamic) schools supervised and financed by the Department of Religious Affairs.[203] The enrolment rate is 94% for primary education (2011), 75% for secondary education, and 27% for tertiary education. The literacy rate is 93% (2011).[204]

By 2014, there were 118 state universities in Indonesia. Entry to higher education depends on the nationwide entrance examination (SNMPTN and SBMPTN). According to the 2015 Times Higher Education World University Rankings, the top university in Indonesia is University of Indonesia (rank 310, dropped from 201 in 2009), followed by Bandung Institute of Technology (in the 431-460 rank range) and Gadjah Mada University (in the 551–600 rank range). Five other Indonesian universities, including Airlangga University, Bogor Institute of Agriculture, Diponegoro University, Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology and Brawijaya University all huddled in the 701+ range.[205] All of educational institutions located in Java. Andalas University is pioneering the establishment of a leading university outside of Java.[206]

Language

More than 700 regional languages are spoken in Indonesia's numerous islands.[207] Most belong to the Austronesian language family, with a few Papuan languages also spoken. The official language is Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian language), a variant of Malay,[208] which was used in the archipelago. It borrows heavily from local languages such as Javanese, Sundanese, Minangkabau, etc. Indonesian is primarily used in commerce, administration, education and the media, but most Indonesians speak other languages, such as Javanese, as their first language.[207]

Indonesian is based on the prestige dialect of Malay, that of the Johor-Riau Sultanate, which for centuries had been the lingua franca of the archipelago. It is the official language of Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei. Indonesian is universally taught in schools and consequently is spoken by nearly every Indonesian. It is the language of business, politics, national media, education, and academia. It was promoted by Indonesian nationalists in the 1920s, and declared the official language under the name Bahasa Indonesia in the proclamation of independence in 1945. Most Indonesians speak at least one of several hundred local languages and dialects, often as their first language. In comparison, Papua has over 270 indigenous Papuan and Austronesian languages,[209] in a region of about 2.7 million people. Javanese is the most widely spoken local language, as it is the language of the largest ethnic group.[87]

Sports

Sports in Indonesia are generally male-oriented and spectator sports are often associated with illegal gambling.[210] The most popular sports are badminton and football. Indonesian players have won the Thomas Cup (the world team championship of men's badminton) thirteen of the twenty-six times that it has been held since 1949, as well as numerous Olympic medals since the sport gained full Olympic status in 1992. Indonesian women have won the Uber Cup, the female equivalent of the Thomas Cup, 3 times, in 1975, 1994 and 1996. Liga Super Indonesia is the country's premier football club league. On the international stage, Indonesia experienced limited success despite being the first Asian team to qualify for the FIFA World Cup in 1938 as Dutch East Indies.[211] In 1956, the football team played in the Olympics and played a hard-fought draw against the Soviet Union. On the continent level, Indonesia won the bronze medal once in football in the 1958 Asian Games. Indonesia's first appearance in Asian Cup was back in 1996. The Indonesian national team qualified for the Asian Cup in 2000, 2004 and 2007 AFC Asian Cup, however unable to move through next stage.

Boxing is a popular combative sport spectacle in Indonesia. Some of famous Indonesian boxers are Ellyas Pical, three times IBF Super flyweight champion; Nico Thomas, Muhammad Rachman, and Chris John.[212] Traditional sports include sepak takraw, and bull racing in Madura. In areas with a history of tribal warfare, mock fighting contests are held, such as caci in Flores and pasola in Sumba. Pencak Silat is an Indonesian martial art and in 1987, became one of the sporting events in Southeast Asian Games, with Indonesia appearing as one of the leading forces in this sport. In Southeast Asia, Indonesia is one of the major sport powerhouses by winning the Southeast Asian Games 10 times since 1977.

Tourism

Both nature and culture are major components of Indonesian tourism. The natural heritage can boast a unique combination of a tropical climate. These natural attractions are complemented by a rich cultural heritage that reflects Indonesia's dynamic history and ethnic diversity, that 719 living languages are used across the archipelago. The ancient Prambanan and Borobudur temples, Toraja and Bali, with its Hindu festivities, are some of the popular destinations for cultural tourism.

Indonesia has a well-preserved natural ecosystem with rainforests that stretch over about 57% of Indonesia's land (225 million acres), approximately 2% of which are mangrove systems. Forests on Sumatra and Kalimantan are examples of popular tourist destinations. Moreover, Indonesia has one of longest coastlines in the world, measuring 54,716 kilometres (33,999 mi).

With 20% of the world's coral reefs, over 3,000 different species of fish and 600 coral species, deep water trenches, volcanic sea mounts, World War II wrecks, and an endless variety of macro life, scuba diving in Indonesia is both excellent and inexpensive.[213] Bunaken National Marine Park, at the northern tip of Sulawesi, claims to have seven times more genera of coral than Hawaii,[214] and has more than 70% of all the known fish species of the Indo-Western Pacific Ocean.[215] According to Conservation International, marine surveys suggest that the marine life diversity in the Raja Ampat Islands is the highest recorded on Earth.[216] Moreover, there are over 3,500 species living in Indonesian waters, including sharks, dolphins, manta rays, turtles, morays, cuttlefish, octopus and scorpaenidae, compared to 1,500 on the Great Barrier Reef.

Indonesia has 8 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, such as the Komodo National Park, Ujung Kulon National Park, Lorentz National Park, Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra, comprises three national parks on the island of Sumatra: Gunung Leuser National Park, Kerinci Seblat National Park and the Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park;[217] and 18 World Heritage Sites in tentative list, such as the historic urban centres of Jakarta Old Town, Sawahlunto Old Coal Mining Town, Semarang Old Town, as well as Muara Takus Compound Site.

The heritage tourism is focussed on specific interest on Indonesian history, such as colonial architectural heritage of Dutch East Indies era. The colonial heritage tourism mostly attracted visitors from the Netherlands that share historical ties with Indonesia, as well as Indonesian or foreign colonial history enthusiast. The activities among others are visiting museums, churches, forts and historical colonial buildings, as well as spend some nights in colonial heritage hotels. The popular heritage tourism attractions are Jakarta Old Town and Sawahlunto Old Coal Mining Town. The heritage tourism might also focussed on the era of 17th-to 19th-century royal Javanese courts of Yogyakarta Sultanate, Surakarta Sunanate and the Mangkunegaran Palace.

Urban tourism activities includes shopping, sightseeing in big cities, or enjoying modern amusement parks, resorts, spas, nightlife and entertainment. Beautiful Indonesia Miniature Park as well as Ancol Dreamland with Dunia Fantasi (Fantasy World) theme park and Atlantis Water Adventure are Jakarta's answer to Disneyland-style amusement park and water park. Several similar theme parks also developed in other cities, such as Trans Studio Makassar and Trans Studio Bandung. The capital city, Jakarta, is a shopping hub in the country and also one of the best places to shop in Southeast Asia. The city has numerous shopping malls and traditional markets. With a total of 550 hectares, Jakarta has the world's largest shopping mall floor area within a single city.[218] The annual "Jakarta Great Sale" is held every year in June and July to celebrate Jakarta's anniversary, with about 73 participating shopping centres in 2012.[219] Bandung is a popular shopping destination for fashion products among Malaysians and Singaporeans.[220]

Since January 2011, Wonderful Indonesia has been the slogan of an international marketing campaign directed by the Indonesian Ministry of Culture and Tourism to promote tourism.[221] In year 2014, 9.4 million international visitors entered Indonesia,[222] staying in hotels for an average of 7.5 nights and spending an average of US$1,142 per person during their visit, or US$152.22 per person per day.[223]

Culture

Indonesia has about 300 ethnic groups, each with cultural identities developed over centuries, and influenced by Indian, Arabic, Chinese, and European sources. Traditional Javanese and Balinese dances, for example, contain aspects of Hindu culture and mythology, as do wayang kulit (shadow puppet) performances. Textiles such as batik, ikat, ulos and songket are created across Indonesia in styles that vary by region. The Indonesian film industry's popularity peaked in the 1980s and dominated cinemas in Indonesia,[224] although it declined significantly in the early 1990s.[225] Between 2000 and 2005, the number of Indonesian films released each year has steadily increased.[224] Indonesia holds 6 items UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Architecture

Architecture reflects the diversity of cultural that have shaped Indonesia as a whole. Invaders, colonisers, missionaries, merchants and traders brought cultural changes that had a profound effect on building styles and techniques. The most dominant influences on Indonesian architecture have traditionally been Indian; however, Chinese, Arab, and European architectural influences have been significant. The Indonesia traditional houses are at the centre of a web of customs, social relations, traditional laws, taboos, myths and religions that bind the villagers together. The house provides the main focus for the family and its community, and is the point of departure for many activities of its residents.

Example of Indonesian vernacular architecture including Toraja's Tongkonan, Minangkabau's Rumah Gadang and Rangkiang, Javanese style Pendopo pavilion with Joglo style roof, Dayak's longhouses, various Malay houses, Balinese houses and temples, and also various styles of lumbung (rice barns).

Music

The music in Indonesia predates historical records, various native Indonesian tribes often incorporate chants and songs accompanied with musics instruments in their rituals. The Indonesian traditional instruments includes angklung, kacapi suling, siteran, gong, gamelan, degung, gong kebyar, bumbung, talempong, kulintang and sasando.

The diverse world of Indonesian music genres was the result of the musical creativity of its people, and also the subsequent cultural encounters with foreign musical influences into the archipelago. Next to distinctive native form of musics, several genres can traces its origin to foreign influences; such as gambus and qasidah from Middle Eastern Islamic music,[226] keroncong from Portuguese influences,[227] and dangdut—one of the most popular music genres in Indonesia—with notable Hindi music influence as well as Malay orchestras.[228]

Today, Indonesian music industry enjoys nationwide popularity. Thanks to common culture and intelligible languages between Indonesian and Malay, Indonesian music enjoyed regional popularity in neighbouring countries such as Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. However, the overwhelming popularity of Indonesian music in Malaysia had alarmed the Malaysian music industry. In 2008, Malaysian music industry demanded the restriction of Indonesian songs on Malaysian radio broadcasts.[229]

Dance

Traditional dance of Indonesia reflect the rich diversity of Indonesian people. The dance traditions in Indonesia; such as Javanese, Sundanese, Minangkabau, Balinese, Malays, Acehnese and many other dances traditions are age old traditions, yet also a living and dynamic traditions. Several royal houses; the istanas and keratons still survived in some parts of Indonesia and become the haven of cultural conservation. The obvious difference between courtly dance and common folk dance traditions is the most evident in Javanese dance. The palace court traditions also evident in Balinese and Malay court which usually imposed refinement and prestige. Sumatran courtly culture such as the remnant of Aceh Sultanate and Palembang Sultanate, are more influenced by Islamic culture, while Java and Bali are more deeply rooted in their Hindu-Buddhist heritage.

Dances in Indonesia are believed by many scholars to have had their beginning in rituals and religious worship.[230] Such dances are usually based on rituals, like the war dances, the dance of witch doctors, and dance to call for rain or any agricultural related rituals such as Hudoq dance ritual of Dayak people. In Bali, dances has become the integral part of Hindu Balinese rituals. Sacred ritual dances performed only in Balinese temples such as sacred Sanghyang dedari and Barong dance.

The commoners folk dance is more concerned with social function and entertainment value than rituals. The Javanese Ronggeng and Sundanese Jaipongan is the fine example of this common folk dance traditions. Both are social dances that are more for entertainment purpose than rituals. Randai is a folk theatre tradition of the Minangkabau people which incorporates dance, music, singing, drama and the martial art of silat.[231] Certain traditional folk dances has been developed into mass dance with simple but structurised steps and movements, such as Poco-poco dance from Minahasa and Sajojo dance from Papua.

Cinema

The first domestically produced film in the Indies was in 1926: Loetoeng Kasaroeng, a silent film by Dutch director L. Heuveldorp. This adaptation of the Sundanese legend was made with local actors by the NV Java Film Company in Bandung.

After independence, the film industry expanded rapidly, with six films made in 1949 rising to 58 in 1955. Djamaluddin Malik's Persari often emulating American genre films and the working practices of the Hollywood studio system, as well as remaking popular Indian films.[232] The Sukarno government used cinema for nationalistic, anti-Western purposes. Foreign film imports were banned. After the overthrow of Sukarno by Suharto's New Order regime, films were regulated through a censorship code that aimed to maintain the social order.[233] Usmar Ismail, a director from West Sumatra made a major imprint in Indonesian film in the 1950s and 1960s.[234]

The industry reached its peak in the 1980s, with such successful films as Nagabonar (1987) and Catatan Si Boy (1989). Warkop's comedy films, directed by Arizal also proved to be successful. The industry has also found appeal among teens with such fare as Pintar-pintar Bodoh (1982), and Maju Kena Mundur Kena (1984). Actors during this era included Deddy Mizwar, Eva Arnaz, Meriam Bellina, and Rano Karno.[235]

Under the Reformasi movement, independent filmmaking was a rebirth of the filming industry in Indonesia, where film's started addressing topics which were previously banned such as; religion, race, love and other topics.[233] Riri Riza and Mira Lesmana were the new generation of Indonesian film figures who co-directed of Kuldesak (1999), Petualangan Sherina (2000), Ada Apa dengan Cinta? (2002), Gie (2005), and Laskar Pelangi (2008).[236] Locally made film quality has gone up in 2012, this is attested by the international release of films such as The Raid: Redemption, Modus Anomali, Dilema, Lovely Man, and Java Heat.

Literature

The oldest evidence of writing in Indonesia is a series of Sanskrit inscriptions dated to the 5th century. Many of Indonesia's peoples have strongly rooted oral traditions, which help to define and preserve their cultural identities.[237] In written poetry and prose, a number of traditional forms dominate, mainly syair, pantun, gurindam, hikayat and babad. Some of these works are Syair Raja Siak, Syair Abdul Muluk, Hikayat Abdullah, Hikayat Bayan Budiman, Hikayat Hang Tuah, Sulalatus Salatin, and Babad Tanah Jawi.[238]

Early modern Indonesian literature originates in Sumatran tradition.[239] Balai Pustaka, the government bureau for popular literature, was instituted around 1920 to promote the development of indigenous literature, it adopted Malay as the preferred common medium for Indonesia. Important figures in modern Indonesian literature include: Dutch author Multatuli, who criticised treatment of the Indonesians under Dutch colonial rule; Sumatrans Mohammad Yamin and Hamka, who were influential pre-independence nationalist writers and politicians;[240] and proletarian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Indonesia's most famous novelist.[241][242] Pramoedya earned several accolades, and was frequently discussed as Indonesia's and Southeast Asia's best candidate for a Nobel Prize in Literature.[243]

Indonesian literature and poetry flourished even more in the first half of the 20th century. Chairil Anwar was considered as the greatest literary figure of Indonesia by American poet and translator, Burton Raffel.[244] He was among those youngsters who pioneered in changing the traditional Indonesian literature and modifying it on the lines of the newly independent country. Some of his popular poems include Krawang-Bekasi, Diponegoro and Aku. Other major authors include Marah Roesli (Sitti Nurbaya), Merari Siregar (Azab dan Sengsara), Abdul Muis (Salah Asuhan), Djamaluddin Adinegoro (Darah Muda), Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana (Layar Terkembang), and Amir Hamzah (Nyanyi Sunyi) whose works are among the most well known in Maritime Southeast Asia.[245]

Cuisine

Indonesian cuisine varies by region and is based on Chinese, European, Middle Eastern, and Indian precedents.[246] Rice is the main staple food and is served with side dishes of meat and vegetables. Spices (notably chili), coconut milk, fish and chicken are fundamental ingredients.[247]

Media

Media freedom in Indonesia increased considerably after the end of President Suharto's rule, during which the now-defunct Ministry of Information monitored and controlled domestic media, and restricted foreign media.[248] The TV market includes ten national commercial networks, and provincial networks that compete with public TVRI. Private radio stations carry their own news bulletins and foreign broadcasters supply programs. At a reported 25 million users in 2008,[249] Internet usage was estimated at 12.5% in September 2009.[250] More than 30 million cell phones are sold in Indonesia each year, and 27% of them are local brands.[251]

See also

- List of Indonesia-related topics

- Index of Indonesia-related articles

- Outline of Indonesia

-

Indonesia – Wikipedia book

Indonesia – Wikipedia book

References

- ↑ "Indonesia" (Country Studies ed.). US Library of Congress.

- ↑ Vickers, p. 117

- ↑ "Population Projection by Province, 2010-2035". Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Indonesia". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2015" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- 1 2 Yang, Heriyanto (August 2005). "The History and Legal Position of Confucianism in Post Independence Indonesia" (PDF). Marburg Journal of Religion 10 (1): 8. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ↑ "The Naming Procedures of Indonesia's Islands", Tenth United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names, New York, 31 July – 9 August 2012, United Nations Economic and Social Council

- ↑ Islam in Indonesia: Contrasting Images and Interpretations

- ↑ Indonesia: A Global Studies Handbook

- ↑ "Poverty in Indonesia: Always with them". The Economist. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2006.; correction.

- ↑ Guerin, G (23 May 2006). "Don't count on a Suharto accounting". Asia Times Online (Hong Kong).

- 1 2 Tomascik, T; Mah, JA; Nontji, A; Moosa, MK (1996). The Ecology of the Indonesian Seas – Part One. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. ISBN 962-593-078-7.

- 1 2 Anshory, Irfan (16 August 2004). "Asal Usul Nama Indonesia" (in Indonesian). Pikiran Rakyat. Archived from the original on 15 December 2006. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- ↑ Earl, George SW (1850). "On The Leading Characteristics of the Papuan, Australian and Malay-Polynesian Nations". Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIAEA): 119.

- ↑ Logan, James Richardson (1850). "The Ethnology of the Indian Archipelago: Embracing Enquiries into the Continental Relations of the Indo-Pacific Islanders". Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIAEA): 4:252–347.

- ↑ Earl, George SW (1850). "On The Leading Characteristics of the Papuan, Australian and Malay-Polynesian Nations". Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIAEA): 254, 277–8.

- 1 2 Justus M van der Kroef (1951). "The Term Indonesia: Its Origin and Usage". Journal of the American Oriental Society 71 (3): 166–71. doi:10.2307/595186. JSTOR 595186.

- ↑ Brown, Colin (2003). A short history of Indonesia: the unlikely nation?. Allen & Unwin. p. 13. ISBN 1-86508-838-2.

- ↑ Choi, Kildo; Driwantoro, Dubel (2007). "Shell tool use by early members of Homo erectus in Sangiran, central Java, Indonesia: cut mark evidence". Journal of Archaeological Science 34: 48. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.03.013.

- ↑ Finding showing human ancestor older than previously thought offers new insights into evolution. Terradaily.com. 5 July 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ Pope, GG (1988). "Recent advances in far eastern paleoanthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology 17: 43–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.17.100188.000355. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, RE; Suraya AA (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. pp. 309–12.; Pope, GG (1983). "Evidence on the age of the Asian Hominidae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 80 (16): 4988–92. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.16.4988. PMC 384173. PMID 6410399. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, RE; Suraya AA (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. p. 309.; de Vos, JP; PY Sondaar (1994). "Dating hominid sites in Indonesia". Science 266 (16): 4988–92. doi:10.1126/science.7992059. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, RE; Suraya AA (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. p. 309.

- ↑ "The Great Human Migration". Smithsonian. July 2008: 2.

- 1 2 Taylor, pp. 5–7

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 15–18

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 3, 9–11, 13–5, 18–20, 22–3

- ↑ Vickers, pp. 18–20, 60, 133–4

- ↑ Taylor (2003), pp. 22-26; Ricklefs (1991), p. 3

- ↑ Peter Lewis (1982). "The next great empire". Futures 14 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(82)90071-4.

- ↑ Ricklefs (1991), pp. 3–14

- ↑ Ricklefs (1991), pp. 12-14

- ↑ Ricklefs (1991), pp. 22-24

- ↑ Ricklefs (1991), p. 24

- ↑ Ricklefs, p. 24

- ↑ Schwarz, pp. 3–4, writes: "Dutch troops were constantly engaged in quelling rebellions both on and off Java. The influence of local leaders such as Prince Diponegoro in central Java, Imam Bonjol in central Sumatra and Pattimura in Maluku, and a bloody thirty-year war in Aceh weakened the Dutch and tied up the colonial military forces."

- ↑ Ricklefs (1991); Gert Oostindie and Bert Paasman (1998). "Dutch Attitudes towards Colonial Empires, Indigenous Cultures, and Slaves". Eighteenth-Century Studies 31 (3): 349–55. doi:10.1353/ecs.1998.0021.

- ↑ Indonesia: World War II and the Struggle For Independence, 1942–50; The Japanese Occupation, 1942–45, Library of Congress, 1992

- ↑ Cited in: Dower, John W. War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986; Pantheon; ISBN 0-394-75172-8)

- ↑ HJ Van Mook (1949). "Indonesia". Royal Institute of International Affairs 25 (3): 274–85. JSTOR 3016666.; Charles Bidien (5 December 1945). "Independence the Issue". Far Eastern Survey 14 (24): 345–8. doi:10.1525/as.1945.14.24.01p17062. JSTOR 3023219.; Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and History. Yale University Press. p. 325. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.; Reid (1973), p. 30

- ↑ Charles Bidien (5 December 1945). "Independence the Issue". Far Eastern Survey 14 (24): 345–8. doi:10.1525/as.1945.14.24.01p17062. JSTOR 3023219.; "Indonesian War of Independence". Military. Global Security. Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- ↑ Indonesia's 1969 Takeover of West Papua Not by "Free Choice". National Security Archive, Suite 701, Gelman Library, The George Washington University.

- ↑ Ricklefs, pp. 237–280

- ↑ Friend, pp. 107–109

- ↑ Chris Hilton (writer and director) (2001). Shadowplay (Television documentary). Vagabond Films and Hilton Cordell Productions.

- ↑ Ricklefs, pp. 280–283, 284, 287–290

- ↑ John Roosa and Joseph Nevins (5 November 2005). "40 Years Later: The Mass Killings in Indonesia". CounterPunch. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ↑ Robert Cribb (2002). "Unresolved Problems in the Indonesian Killings of 1965–1966". Asian Survey 42 (4): 550–563. doi:10.1525/as.2002.42.4.550.

- ↑ John D. Legge (1968). "General Suharto's New Order". Royal Institute of International Affairs 44 (1): 40–47. JSTOR 2613527.

- ↑ US National Archives, RG 59 Records of Department of State; cable no. 868, ref: Embtel 852, 5 October 1965.

- ↑ Vickers, p. 163

- ↑ David Slater, Geopolitics and the Post-Colonial: Rethinking North–South Relations, London: Blackwell, p. 70

- ↑ Ricklefs

- ↑ Vickers

- ↑ Schwarz

- ↑ Delhaise, Philippe F (1998). Asia in Crisis: The Implosion of the Banking and Finance Systems. Willey. p. 123. ISBN 0-471-83450-5.

- ↑ "President Suharto resigns". BBC. 21 May 1998. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ↑ Burr, W.; Evans, M.L. (6 December 2001). "Ford and Kissinger Gave Green Light to Indonesia's Invasion of East Timor, 1975: New Documents Detail Conversations with Suharto". National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 62. National Security Archive, The George Washington University, Washington, DC. Retrieved 17 September 2006.; "International Religious Freedom Report". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. US: Department of State. 17 October 2002. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2006.

- ↑ Robert W. Hefner (2000). "Religious Ironies in East Timor". Religion in the News 3 (1). Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ↑ "Aceh rebels sign peace agreement". BBC. 15 August 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ↑ In 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001

- 1 2 Susi Dwi Harijanti and Tim Lindsey (2006). "Indonesia: General elections test the amended Constitution and the new Constitutional Court". International Journal of Constitutional Law 4 (1): 138–150. doi:10.1093/icon/moi055.

- ↑ "The Carter Center 2004 Indonesia Election Report" (PDF) (Press release). The Carter Center. 2004. Retrieved 13 December 2006.

- ↑ (2002), The fourth Amendment of 1945 Indonesia Constitution, Chapter III – The Executive Power, Art. 7.

- ↑ People's Consultative Assembly (MPR-RI). Ketetapan MPR-RI Nomor II/MPR/2000 tentang Perubahan Kedua Peraturan Tata Tertib Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat Republik Indonesia (PDF) (in Indonesian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 "Background Note: Indonesia". U.S. Library of Congress. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ↑ Reforms include total control of statutes production without executive branch interventions; all members are now elected (reserved seats for military representatives have now been removed); and the introduction of fundamental rights exclusive to the DPR. (see Harijanti and Lindsey 2006)

- ↑ Based on the 2001 constitution amendment, the DPD comprises four popularly elected non-partisan members from each of the thirty-three provinces for national political representation. People's Consultative Assembly (MPR-RI). Third Amendment to the 1945 Constitution of The Republic of Indonesia (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2006.

- 1 2 "Country Profile: Indonesia" (PDF). U.S Library of Congress. December 2004. Retrieved 9 December 2006.

- ↑ Wong, Kristina (23 July 2009). "abc NEWS Poll: Obama's Popularity Lifts U.S. Global Image". USA: ABC. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia – Foreign Policy". U.S. Library of Congress. U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ↑ Indonesia temporarily withdrew from the UN on 20 January 1965 in response to Malaysia being elected as a non-permanent member of the Security Council. It announced its intention to "resume full cooperation with the United Nations and to resume participation in its activities" on 19 September 1966, and was invited to re-join the UN on 28 September 1966.

- ↑ Chris Wilson (11 October 2001). "Indonesia and Transnational Terrorism". Foreign Affairs, Defense and Trade Group. Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 15 October 2006.; Reyko Huang (23 May 2002). "Priority Dilemmas: U.S. – Indonesia Military Relations in the Anti Terror War". Terrorism Project. Center for Defense Information.

- ↑ "Commemoration of 3rd anniversary of bombings". Melbourne: The Age Newspaper. AAP. 10 December 2006.

- ↑ "Travel Warning: Indonesia" (Press release). US Embassy, Jakarta. 10 May 2005. Archived from the original on 11 November 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- ↑ Chew, Amy (7 July 2002). "Indonesia military regains ground". CNN Asia. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ↑ Witular, Rendi A. (19 May 2005). "Susilo Approves Additional Military Funding". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ↑ Friend, pp. 473–475, 484

- ↑ Friend, pp. 270–273, 477–480

- ↑ "Indonesia flashpoints: Aceh". BBC News (BBC). 29 December 2005. Retrieved 20 May 2007.

- ↑ "Indonesia agrees Aceh peace deal". BBC News (BBC). 17 July 2005. Retrieved 20 May 2007.; Harvey, Rachel (18 September 2005). "Indonesia starts Aceh withdrawal". BBC News (BBC). Retrieved 20 May 2007.

- ↑ Lateline TV Current Affairs (20 April 2006). "Sidney Jones on South East Asian conflicts" (PDF). TV Program transcript, Interview with South East Asia director of the International Crisis Group (Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC)). Archived from the original on 18 September 2006.; International Crisis Group (5 September 2006). "Papua: Answer to Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). Update Briefing (International Crisis Group) (53): 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2006. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- ↑ Michelle Ann Miller (2004). "The Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam law: a serious response to Acehnese separatism?". Asian Ethnicity 5 (3): 333–351. doi:10.1080/1463136042000259789.

- ↑ The positions of governor and its vice governor are prioritized for descendants of the Sultan of Yogyakarta and Paku Alam, respectively, much like a sultanate. (Elucidation on the Indonesia Law No. 22/1999 Regarding Regional Governance. People's Representative Council (1999). Chapter XIV Other Provisions, Art. 122; Indonesia Law No. 5/1974 Concerning Basic Principles on Administration in the Region PDF (146 KB) (translated version). The President of Republic of Indonesia (1974). Chapter VII Transitional Provisions, Art. 91)

- ↑ Part of the autonomy package was the introduction of the Papuan People's Council, which was tasked with arbitration and speaking on behalf of Papuan tribal customs. However, the implementation of the autonomy measures has been criticized as half-hearted and incomplete. Dursin, Richel; Kafil Yamin (18 November 2004). "Another Fine Mess in Papua". Editorial. The Jakarta Post. p. 6.

- ↑ "Papua Chronology Confusing Signals from Jakarta". International NGO Forum on Indonesian Development. 18 November 2004. Archived from the original on 15 January 2006. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- 1 2 3 "Indonesia". CIA. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- 1 2 Witton, Patrick (2003). Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. pp. 139, 181, 251, 435. ISBN 1-74059-154-2.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (17 October 2006). "Rank Order Area". The World Factbook. US CIA, Washington, DC. Retrieved 3 November 2006.

- ↑ "Population density – Persons per km2 2006". CIA world factbook. Photius Coutsoukis. 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2006.

- 1 2 Calder, Joshua (3 May 2006). "Most Populous Islands". World Island Information. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- ↑ "Republic of Indonesia". Encarta. Microsoft. 2006. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009.

- ↑ "Volcanoes of Indonesia". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ↑ "The Human Toll". UN Office of the Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery. United Nations. Archived from the original on 19 May 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ↑ Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. pp. 95–97.

- ↑ "About Jakarta And Depok". University of Indonesia. University of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ↑ Brown, Lester R. (1997). State of the World 1997: A Worldwatch Institute Report on Progress Toward a Sustainable Society (14th edition). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 7. ISBN 0-393-04008-9.

- ↑ "Indonesia's Natural Wealth: The Right of a Nation and Her People". Islam Online. 22 May 2003. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ↑ "Globalis-Indonesia". Globalis, an interactive world map. Global Virtual University. Retrieved 14 May 2007.