Wild West shows

Wild West shows were traveling vaudeville performances in the United States and Europe. The first and prototypical Wild West show was Buffalo Bill's, formed in 1883 and lasting until 1913. The shows introduced many western performers and personalities, and a romanticized version of the American Old West, to a wide audience with many different members. Will Rogers also toured a Wild West show.

Introduction

The mythology and legends of the American West evoke images of adventure filled with cowboys, Indians, wild animals, wild parties with outlaws, and stagecoaches. The real American West of the 19th century was not nearly as glamorous as often depicted. Cowboys, Native American Indians, army scouts, outlaws, and wild animals did truly exist in the West. However, gunfights, stagecoach attacks, and train holdups were not an everyday ordeal. The dramatic myth of the Wild West as we see it today is really a “puffed-up exaggeration”[1] of the real western frontier. The shaping of this myth of western life was aided into creation by films, dime novels, live performances, paintings, pulp magazines, sculptures, and television. More than anyone or anything else, William Frederick Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill, can be credited with helping to create and preserve a lasting legend of the West. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show took the reality of western life and glamorized it into an appealing show for Eastern audiences and helped to permanently preserve the legend of the Wild West.

The "Real" Wild West

“Cowboys driving cattle over open range. Outlaws and lawmen facing one another on a dusty main street. Indian hunters racing through buffalo herds on horseback. These images, so familiar from books and movies, are what come to mind when many people think of the American West.”[2] Although these images are not entirely fictionalized, the real American West was home to European settlers and pioneers. The show helped develop dramatic images of the "wild west" and the west was a place open for imagination and new starts.

Some lucky settlers or people flocking to the west found this promise of a better life fulfilled. These are the people who made the myth of the west true. However, for many others the promise did not come through. For them life was rough and the truth of the west was rougher. Still, a promise for the struggling people of eastern cities, suburban, and rural areas was a nice idea. It gave them hope and a bit of assurance that their hardships were not forever or in vain. The development of Wild West shows were a way to preserve this open promise- without the failure that it often presented in reality. For Native Americans, of course, the back side of the medal was a constantly lived reality, where the Wild West's 'frontier' was a battle front taking over traditional lands.

Wild West shows were shows that took the reality of the West and glamorized it for the eastern audiences to give it an exciting appeal. The showmen who ran the shows adapted western life to fit an exaggerated yet captivating image which the eastern audiences both expected and were intrigued by. The shows were a marriage of reality and theater and were designed by the showmen to be both “authentic” and entertaining, a balance which sought to not flat out fabricate, but only enhance truth. Some shows even claimed educational benefits. The shows were “Romance and reality, adventure and ‘the story of our country’”.[3]

Myth vs. reality: what are Wild West shows?

Perhaps part of the popularity of Wild West shows can be attributed to the feeling of celebration and conquest they evoked. They celebrated the achievement of the frontier movement as being the most important accomplishment in American history. The shows were a winning combination of history, patriotism, and adventure which managed to create an enduring spirit of the "unsettled" west and capture audience’s hearts throughout America and Europe.

Wild West shows contained a lot of action. Wild animals, trick performances, theatrical reenactments, and all sorts of characters from the frontier were all incorporated into the show’s program.

Theatrical reenactments included those of battle scenes, “characteristic” western scenes, and even hunts. Shooting exhibitions were also in the line up with extensive shooting displays and trick shots. Competitions that came in the form of races between combinations of people or animals exhilarated and stimulated the audience. Equally exciting were rodeo events, involving rough and “dangerous” activities performed by cowboys with different animals. In short, Wild West shows began to include any type of “western” event that could in any way appeal to the audiences.

Those watching the show would have been credulous and excited by the idea of a rough, wild frontier. They were enthralled by the west, and Wild West shows were the answer to popular demands. Wild West shows preserved the disappearing world of the "unsettled" and "untamed" west and brought it to life for audiences.

Popularity

Around the start of the 20th century, Wild West shows were extremely popular. Within the first two years of the first Wild West show, over 10,000,000 spectators had seen it and it had a profit of $100,000. The reason for their popularity existed simply in the basis that easterners were immensely attracted to them. Easterners were eager to enjoy the thrill and danger of the west, and in this way it was made possible to do so without the risks and consequences that came along with the real west. The Wild West shows satisfied their cravings for adventure.

Other shows

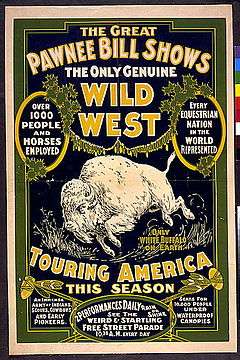

Over time, various Wild West shows were developed. They were started by people with generally flamboyant names such as Dr. W.F. Carver, Pawnee Bill, "Buckskin Joe" Hoyt,[4] and Mexican Joe. Blacks (such as Bill Pickett - the famous bulldogger from the 101 Ranch Wild West Show - his brothers, and Voter Hall - billed as a "Feejee Indian from Africa"[5]), Mexicans (such as the Esquivel Brothers from San Antonio[5]), Native Americans (including the illustrious war leader Red Cloud[5]), and women also tried their hand in the business,[5] with such names headlining as Calamity Jane, Luella-Forepaugh Fish,[6] the Kemp Sisters,[7] May Lillie, Lucille Mulhall, Annie Oakley, and Lillian Smith. Tillie Baldwin also made a name for herself as a performer, as did Texas Rose as an announcer.[7] Of all the shows, the first, most famous and most successful was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World; this was the show that started it all.

Buffalo Bill

Buffalo Bill was born William Frederick Cody on February 26, 1846. He lived until January 10, 1917. Cody grew up on the frontier and loved his way of life. As he got older, some of his titles he earned included buffalo hunter, U.S. Army scout and guide, and showman, as well as Pony Express Rider, Indian fighter, and even author. Whatever Cody’s titles, he was destined for fame.

His track of fame began as with his reputation as a master buffalo hunter. While hunting buffalo for pay to feed railroad workers, he shot and killed 11 out of 12 buffalo, earning him his nickname and show name “Buffalo Bill.” As an army scout, Cody extended his fame by gaining recognition as an army scout with a reputation for bravery. As a well-known scout, he often led rich men from the East and Europe and even royalty on hunting trips. Cody’s fame began to spread to the East when an author, Ned Buntline caught wind of him and wrote a dime novel about Buffalo Bill, called Buffalo Bill, the King of Border Men (1869). To top it all off, Buntline’s novel was turned into a theatrical production which greatly contributed to his success and popularity in the east.

Before long, Cody ended up starring as himself in Buntline’s play. Soon after, he started his own theatrical troop. It wasn’t until 1883 when Cody first got his idea for a Wild West show. That same year, he launched Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in Omaha, Nebraska. With his Wild West show in hand, nobody could deny Buffalo Bill’s fame. “At the turn of the twentieth century, William F. Cody was known as ‘the greatest showman on the face of the earth’”.[8] Cody had full domination of the Wild West show business.

Out of all of his fame-bearing titles, William F. Cody is most celebrated for being the inventor of the Wild West show. His crown title would be impresario, or manager or producer of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. His motivation to produce the show was to preserve the western way of life that he grew up with and loved. Driven by his ambition to keep this way of life from disappearing, Cody turned his “real life adventure into the first and greatest outdoor western show”.[8] Cody did not want to see his way of life vanish without remembrance. Consequently, Cody became the first real Westerner to cash in on the western myth, which others had been writing literature, dime novels, and plays about for some time.

Show content

In creating the Wild West show, Cody also created the myth of the adventuresome, exciting, and outright wild western frontier. Cody helped pitch-in to give the West its image as we see it today. The legend he fathered became a permanent part in America’s history and is still present today. He also was the first to establish the format and content of Wild West shows.

The shows consisted of reenactments of history combined with displays of showmanship, sharp-shooting, hunts, racing, or rodeo style events. Each show was 3–4 hours long and attracted crowds of thousands of people daily. The show began with a parade on horseback. The parade was a major ordeal, an affair that involved huge public crowds and many performers, including the Congress of Rough Riders. The Congress of Rough Riders was composed of marksman from around the world, including the future President Theodore Roosevelt, who marched through the parade on horseback.

Among the composition of the show were “historical” scenes. “The exact scenes changed over time, but were either portrayed as a ‘typical’ event such as the early settlers defending a homestead, a wagon train crossing the plains, or a more specific event such as the Battle of the Little Bighorn”.[9] In both types of events, Buffalo Bill used his poetic license to both glorify himself or others while heightening the villainous mischievousness of the “bad guys” (outlaws or Indians) and to embellish each situation for theatrical enhancement. “Typical” events included acts known as Bison Hunt, Train Robbery, Indian War Battle Reenactment, and the usual grand finale of the show, Attack on the Burning Cabin, in which Indians attacked a settler’s cabin and were repulsed by Buffalo Bill, cowboys, and Mexicans.

A more specific historical event in the show might have been a reenactment of the Battle of Little Bighorn also known as “Custer’s Last Stand”. This event was made into a famous act performed in the show, with Buck Taylor starring as General George Armstrong Custer. In this battle, Custer and all men under his direct command were killed. After Custer is dead, Buffalo Bill rides in, the hero, but he is too late. He avenges Custer by killing and scalping Yellow Hair (also called Yellowhand) which he called the “first scalp for Custer”.[10] This reenactment is exciting for the audience and also stresses Buffalo Bill’s importance, as it suggests that were he to ride in on time, Custer and his men may have been saved.

Shooting competitions and displays of marksmanship were commonly a part of the program. Great feats of skill were shown off using rifles, shot guns, and revolvers. Most people in the show were all good marksmen but many were experts. Buffalo Bill himself was an excellent marksman. It was said that nobody could top him shooting a rifle off the back of a moving horse. Other star shooters were Annie Oakley, Lillian Smith, and Seth Clover.

The show also demonstrated hunts executed by Buffalo Bill, cowboys, and Mexicans, which were staged as they would have been on the frontier, and were accompanied by one of the few remaining buffalo herds in the worlds. “People throughout North America and Europe who had never seen buffalo before felt the rush of being in the middle of the hunt.”[11]

Animals also did their share in the show through rodeo entertainment, an audience favorite. In rodeo events, cowboys like Lee Martin would try to rope and ride broncos. Broncos are unbroken horses that tend to throw or buck their riders. Other wild animals they would attempt to ride or deal with were mules, buffalo, Texas steers, elk, deer, bears, and moose. Some notable cowboys who participated in the events were Buck Taylor (dubbed “The First Cowboy King”), Bronco Bill, James Lawson ("The Roper"), Bill Bullock, Tim Clayton, Coyote Bill, and Bridle Bill.

Races were another form of entertainment employed in the Wild West show. Many different races were held, including those between cowboys, Mexicans, and Indians, a 100 yd foot race between Indian and Indian pony, a race between Sioux boys on bareback Indian ponies, races between Mexican thoroughbreds, and even a race between Lady Riders.

Performers

_edit.jpg)

All in all, the show had a pretty big entourage. It contained as many as 1,200 performers at one time (cowboys, scouts, Indians, military, Mexicans, and men from other heritages), and a large number of many animals including buffalo and Texas Longhorns. Performers in the show were often popular celebrities of the day. Some of the recognizably famous men who took part in the show were Will Rogers, Tom Mix, Pawnee Bill, James Lawson, Bill Pickett, Jess Willard, Mexican Joe, Capt. Adam Bogardus, Buck Taylor, Ralph and Nan Lohse, Antonio Esquibel, and "Capt. Waterman and his Trained Buffalo". Even more famous were Wild Bill Hickok and Johnny Baker. Wild Bill Hickok was well known as a gunfighter and as a marshal, and he was also an established dime novel hero, like Buffalo Bill. His name on the playbill gave a great draw of audiences because they knew him from dime-novels, and he was a genuine scout. Johnny Baker was nicknamed the “Cowboy Kid” and considered to be Annie Oakley’s boy counterpart. Cody originally took him on in the show mainly because he would have been the same age as his own dead son, but little Johnny Baker turned out to be a great success, was very skilled and ended up becoming the arena director.

The list of famous Wild West show participants was not limited to men. Women were also a large part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show and attracted many spectators. In fact Annie Oakley, one of the show’s star attractions was a woman. Born Phoebe Ann Moses, Oakley first gained recognition as a sharpshooter when she defeated Frank Butler, a pro marksman at age 15, in a shooting exhibition. She became the star attraction of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show for 16 years, under the management of Frank Butler, whom she ended up marrying. Annie was billed in the show as “Miss Annie Oakley, the Peerless Lady Wing-Shot”. She was also nicknamed “Little Sure Shot” by Chief Sitting Bull, who was also in the show. Annie was renowned for her trick shots. Annie was able to, from 30 paces, split the edge of a playing card, hit center of ace of spades, shoot down a playing card tossed in air, shatter glass balls thrown in air, hit dimes held between Butler’s fingers, shoot an apple out of poodle’s mouth and shoot off the butt of cigarette from Butler’s mouth. She also performed the last trick shooting the cigarette out of Crown Prince Wilhelm’s mouth in Berlin. Her most famous trick was a mirror trick in which she hit a target behind her shooting backwards using a mirror for aim. These incredible feats of marksmanship amazed and excited people and she generated huge audiences eager to see the display

Calamity Jane (or Martha Cannary) was another distinguished woman participant of the show. Calamity Jane was a notorious frontierswoman who was the subject of many wild stories- many of which she made up herself. In the show, she was a skilled horsewoman and expert rifle and revolver handler. She also claimed to have a love affair with Wild Bill Hickok (and that she was married to him and had his child), which he denied and there is no proof of. Calamity Jane appeared in Wild West shows until 1902, when she was reportedly fired for drinking and fighting. Other mentionable females in the business were Lillian Smith and Bessie and Della Ferrel

Native Americans were also a part of Cody’s show. The Native Americans who took part in the show were mostly Plains Indians like the Pawnee and Sioux. They participated in staged “Indian Races” and historic battles, and often appeared in attack scenes attacking whites in which their savagery and wildness was played up. They also performed talented dances, such as the Sioux Ghost Dance. In reality the performance of the ghost dance meant that trouble was brewing and about to break out, but it wasn’t portrayed as such in the show. The Native Americans always wore their best regalia and full war paint. Cody treated them with great respect and paid them adequately. The extent of his respect was demonstrated when he named the Native Americans as “the former foe, present friend, the American”. Audiences were impressed by the presence of Native Americans in the show because they were extraordinarily “simultaneously exotic and accessible people”.[12]

Native Americans in the show also had their claim to fame, the best known being Chief Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull joined the show for a short time and was a star attraction alongside Annie Oakley. It was said that he only agreed to join the show because he was fascinated with Annie Oakley and Buffalo Bill assured him that if he joined, he could see her perform all the time. During his time at the show, Sitting Bull was introduced to President Grover Cleveland, which he thought proved his importance as chief. He was friends with Buffalo Bill and highly valued the horse that was given to him when he left the show. Other familiar Native Americans names who performed in the show were Chief Joseph, Geronimo, and Rains in Face (who reportedly killed George A. Custer).

Tour history

Buffalo’s Bill’s Wild West show continued to captivate audiences and tour annually for a total of 30 years (1883–1913). After opening on May 19, 1883 in Omaha, Nebraska, the show was on what seemed to be a perpetual tour all over the east of America. The show “hopped the pond” in 1887 for the American Exhibition, and was then requested for a command performance at Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887 at Windsor Castle, in England. The whole troupe including 200 passengers plus 97 Natives, 18 buffalo, 181 horses, 10 elk, 4 donkeys, 5 longhorns (Texas steers), 2 deer, 10 mules, and the Deadwood Concord stagecoach crossed the Atlantic on several ships. They then toured England for the next six months and the following year returned to tour Europe until 1892. With his tour in Europe, Buffalo Bill established the myth of the American West overseas as well. To some Europeans, the Wild West show not only represented the west, but all of America. He also created the cowboy as an American icon. He gave the people of England, France, Spain, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Germany a taste of the wild and romantic west.

In 1893 the show performed at the Chicago World’s Fair to a crowd of 18,000. This performance was a huge contributor to the show’s popularity. The show never again did as well as it did that year. That same year at the Fair, Frederick Turner, a young Wisconsin scholar, gave a speech that pronounced the first stage of American history over. “The frontier has gone”, he declared.[13]

Decline of show

The Lussiure New of England predicted “The Business will degenerate into the hands of men devoid of Buffalo Bill’s exalted simplicity, and much more eager to finger the shillings of the public than to shake the hand of Mother Nature.”[14] By 1894 the harsh economy made it hard to afford tickets. It did not help that the show was routed to go through the South in a year when the cotton was flooded and there was a general depression in the area. Buffalo Bill lost a lot of money and was on the brink of a financial disaster. Soon after, and in an attempt of recovery of monetary balance, Buffalo Bill signed a contract in which he was tricked by Bonfil and Temmen into selling them the show and demoting himself to a mere employee and attraction of the Sells-Floto Circus. From this point, the show began to destroy itself. Finally, in 1913 the show was declared bankrupt. “Cody was forced to take his tents down for the last time”.[15]

Western shows “generated a passion for Western entertainment of all kinds.”[11] This passion is still evidenced in western films, modern rodeos, and circuses. Western Films in the first half of the 20th century filled the gap left behind by Wild West shows. The first real western, The Great Train Robbery was made in 1903, and thousands followed after. Contemporary rodeos also still exist today as major productions, still employing the same events and skills as cowboys did in Wild West shows.

21st century Wild Westing

Wild Westers still perform in movies, pow-wows, pageants and rodeos. Some Oglala Lakota people carry on family show business traditions from Carlisle Indian School alumni who worked for Buffalo Bill and other Wild West shows.[16] Americans and Europeans continue to have a great interest in Native peoples and enjoy modern pow-wow culture. First began in Wild West shows, pow-wow culture is popular with Native Americans throughout the United States and a source of tribal enterprise. Americans and Europeans continue to enjoy traditional Native American skills; horse culture, ceremonial dancing and cooking; and buying Native American art, music and crafts. There are several on-going national projects that celebrate Wild Westers and Wild Westing.

The National Museum of American History's Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian Institution preserves and displays Gertrude Käsebier's photographs, as well as many others by photographers who captured the displays of Wild Westing.

The Carlisle Indian School Resource Center of the Cumberland County Historical Society in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, houses an extensive collection of archival materials and photographs from the Carlisle Indian School. In 2000, the Cumberland County 250th Anniversary Committee worked with Native Americans from numerous tribes and non-natives to organize a pow-wow on Memorial Day to commemorate the Carlisle Indian School, the students and their stories.[17] The Resource Center has over 3,000 photographs and recorded oral histories from school alumni, relatives of former students and local townspeople.[17] Today though many most of the population have changed their view on western culture as it has become less interesting.

See also

- Buffalo Girls (1995 film), depicts Buffalo Bill's Wild West show

- Bullwhip

- Circus

- Circus skills

- Georgian horsemen in Wild West Shows

- Impalement arts

- Knife throwing

- List of Wild West shows

- Sideshow

- Target girl

- Trick roping

- Variety Shows

- Vaudeville

- Wild Westing

References

- ↑ Zadra (1988), p. 23.

- ↑ Sonneborn 2002, p. 5

- ↑ Kasson 2000, p. 56

- ↑ "Buckskin Joe". Arkansas City Republican. 1878–1888.

- 1 2 3 4 Fees, Paul - Former Curator. "Wild West shows: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West". Buffalo Bill Museum.

- ↑ Dinkins, Greg, ed. (2009). Minnesota in 3D: A Look Back in Time: With Built-in Stereoscope Viewer-Your Glasses to the Past! publisher=Voyageur Press.

- 1 2 George-Warren, Holly (2010). The Cowgirl Way: Hats Off to America's Women of the West. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 33.

- 1 2 Pendergast 2000, p. 49

- ↑ Bowling Green State University

- ↑ Sorg 1998 p. 26

- 1 2 Swanson 2004, p. 42

- ↑ Kasson 2000, p. 162

- ↑ Sonneborn 2002, p. 137

- ↑ Sorg 1998 p. 52

- ↑ Sonneborn 2002, p. 117

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.121.

- 1 2 See Linda F. Witmer, the Carlisle Indian School Resource Center, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. http://journals.historicalsociety.com/ftp/ciiswelcome.html. Also see Barbara Landis, "Carlisle Indian Industrial School (1879-1918)", http://home.epix.net/~landis/index.html.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wild West shows. |

- Bowling Green State University (Spring 2000). Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and Exhibition. Bowling Green State University. <http://www.bgsu.edu/departments/acs/1890s/buffalobill/bbwildwestshow.html>

- Kasson, Joy S. (2000). Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Pendergast, Tom and Sara (2000). Westward Expansion Almanac. Boston: UXL of the Gale Group.

- Pendergast, Tom and Sara (2001). Westward Expansion Biographies. Boston: UXL of the Gale Group.

- Sonneborn, Liz (2002). The American West. Scholastic Inc.

- Sorg, Eric (1998). Buffalo Bill: Myth & Reality. Santa Fe: Ancient City Press.

- Swanson, Wayne (2004). Why the West was Wild. Buffalo: Annick Press Ltd.

- Zadra, Dan (1988). We The People; Buffalo Bill. Mankato: Creative Education Inc.

- Buffalo Bill Cody (24 April 2000). The Library of Congress. 29 Nov. 2005. <http://www.americaslibrary.gov/cgi-bin/page.cgi/aa/cody>.

- Buffalo Bill in Show Business (24 April 2000). The Library of Congress. 29 Nov. 2005. <http://www.americaslibrary.gov/cgi-bin/page.cgi/aa/entertain/cody/business_1>

- Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows (24 April 2000). The Library of Congress. 29 Nov. 2005. <http://www.americaslibrary.gov/cgi-bin/page.cgi/aa/entertain/cody/show_1>.

- Dippie, Brian W. "Custer, George Armstrong." 2005. World Book, Inc. 30 Nov. 2005 <http://www.worldbookonline.com/wb/Article?id=ar144680>.

- Faulk, Odie B. “Western frontier life in America” The World Book Encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book Inc., 1995 ed.

- Oakley, Annie (2005). Encyclopædia Britannica. 29 Nov. 2005.<http://concise.britannica.com/ebc/article-9382709>.

- Ruffin, Frances E. (2002). Annie Oakley. Greenville: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

- Savage, William W. Jr. (30 Nov, 2005). “Calamity Jane.” 2005. World Book, Inc. <http://www.worldbookonline.com/wb/Article?id=ar087280>.

- Wild West Shows (2004). The Gale Group, Inc. 29 Nov. 2005. <http://encyclopedias.families.com/wild-west-shows-418-421-erla>.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||