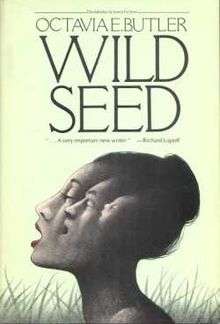

Wild Seed (novel)

First edition cover | |

| Author | Octavia Butler |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | John Cayea [1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Patternist series |

| Genre | Science fiction, Horror |

| Publisher | Doubleday Books |

Published in English | 1980 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and paperback) |

| Pages | 248 pp |

| ISBN | 0-385-15160-8 |

| OCLC | 731027178 |

| Preceded by | Survivor |

| Followed by | Clay's Ark |

Wild Seed is a science fiction novel by writer Octavia Butler. Although published in 1980 as the fourth book of the Patternist series, it is the earliest book in the chronology of the Patternist world. The other books in the series are, in order within the Patternist chronology: Mind of My Mind (1977), Clay's Ark (1984), Survivor (1978), and Patternmaster (1976).

Plot

Wild Seed is a story of two African immortal individuals. Doro is a spirit that can take over other people’s bodies, killing anything in his path, and Anyanwu is a woman with healing powers who can also transform herself into any human or animal shape. Doro senses Anyanwu’s abilities and wants to add her to one of his seed villages in the New World, where he breeds super humans. Doro convinces Anyanwu to travel with him to America by telling her he will give her children she’ll never have to watch die. Doro plans to impregnate her himself, but also wants to share her with his son Isaac. Isaac has very strong telekinetic powers and is one of Doro’s most successful seeds. By partnering Anyanwu and Isaac, Doro hopes to obtain children with very special abilities.

Doro discovers that when Anyanwu transforms into an animal, he cannot sense or kill her. He feels threatened by this ability, and starts to wonder whether he has enough control over her. Anyanwu sees Doro’s disregard for his people and his barbaric ways frighten her. When they arrive at the seed village, Doro tells Anyanwu she is to marry Isaac and bear the children of whoever Doro chooses. Anyanwu eventually agrees once Isaac convinces her that she could be the only one to get through to Doro.

Fifty years later, Doro returns to the seed village. His relationship with Anyanwu has deteriorated, and one of the only things keeping him from killing her is her successful marriage to Isaac. He has come home because he senses that Anyanwu’s daughter, Nweke, is going through the transition of fully coming into her powers. During her transition, Nweke attacks Anyanwu. Trying to protect Anyanwu, Isaac accidentally kills Nweke and suffers a heart attack. Anyanwu realizes she is too weak to heal Isaac and he dies. Afraid that Doro will kill her now that Isaac is not not there to protect her, Anyanwu transforms into an animal and runs away.

After a century, Doro finally tracks Anyanwu down to a Louisiana plantation. To his surprise, Anyanwu has created her own colony, which in many ways is more successful than Doro's. She protects her people until Doro’s arrival, at which point he forces his breeding program on her community. One man he brings to mate with one of Anyanwu’s daughters ruins the harmony of the colony, and several deaths result. Anyanwu becomes tired of Doro’s control, since his immortality makes him the only permanent thing in her life. She decides to commit suicide. Her decision causes Doro to have a change of heart. In desperation, he agrees to compromise as long as she goes on living. From that point on, Doro no longer kills as carelessly, and does not choose his kills from the people that he should be protecting. He also stops using Anyanwu for breeding; from now on she helps him in his quest to try and find more promising seeds, but is more of an ally and partner than his slave.

Characters

Anyanwu

Anyanwu is the story’s black female protagonist. Born in Africa with genetic mutations that endow her with immortality and physical strength, she also possesses a preternatural ability to heal the sick and injured, including herself. Anyanwu is a “shape-shifter,” someone who is capable of altering her cells to create a new identity such as a different body, sex, age, or even species− metamorphoses she calls upon when needed to assure her survival. Although she has the ability to do harm, Anyanwu is a highly moral woman with a strong sense of humanity. Important to Anyanwu are family and community, autonomy and companionship, love and freedom, all of which are threatened when she meets Doro.

Doro

Doro is the story’s antagonist. He too is a mutant, born in Egypt during the reign of the Pharaohs. As he approaches puberty, Doro learns quite accidentally that he is a “body snatcher,” his life extended by killing the nearest person to him and subsuming his/her physical body. His immortality, therefore, is fueled by cruelty, and a desire for power and control. Long ago he became singularly fixated on breeding superhumans to form a psionic society that will provide him with the human bodies he needs, as well as sexual partners. Doro’s qualities are god-like, inducing members of his society to simultaneously fear and revere him. However, there is no one on earth that can satisfy his need for companionship, until he meets Anyanwu.

Isaac

Isaac is Doro’s favorite son. Isaac is physically human in all respects, but possesses an unmatchable telekinetic ability that Doro foremost desires for his constructed society. Doro successfully schemes to mate his son Isaac with his wife Anyanwu as the progenitors of a new lineage of superhumans. The near-incestuous couple form a loving and enduring bond and raise a family together.

Thomas

Thomas is a sickly, drunken, angry, sullen psionic who lives a hermit’s life in the woods. Doro orders Anyanwu to breed with him to teach her a lesson about obedience, as well as to produce a highly gifted child.

Nweke

Ruth Nweke is Anyanwu and Thomas’s daughter, and is raised in the household of Anyanwu and Isaac. Nweke is a promising psionic whose powers are so sensitive that they pose a danger. The outcome of her intense transition into psionic adulthood is a setback for Doro’s eugenics program.

Stephen

Stephen Ifeyinwa is Anyanwu’s son who lives with her in the South on a plantation. She adores him; he is not a product of Doro’s breeding program.

Minor Characters

- Okoye is Anyanwu’s grandson whom she meets in an African slave port.

Udenkwo is Anyanwu’s distant relative. She marries Okoye. - Bernard Daly is Doro’s right-hand man in the slave business.

John Woodley is Doro’s ordinary son and captain of the slave ship. - Lale Sachs is Doro’s “wild” psionic son whom Anyanwu kills in self defense.

- Joseph Toler is a malicious agent planted by Doro in Anyanwu’s Louisiana plantation.

- Helen Obiageli and Margaret Nneka are Anyanwu’s daughters in Louisiana.

- Iye is Stephen Ifeyinwa’s wife.

- Luisa is an elderly woman working for Anyanwu’s family on the plantation, Rita is a cook, and Susan is a field hand.

Themes

She sat staring into the fire again, perhaps making up her mind. Finally, she looked at him, studied him with such intensity he began to feel uncomfortable. His discomfort amazed him. He was more accustomed to making other people uncomfortable. And he did not like her appraising stare—as though she were deciding whether or not to buy him. If he could win her alive, he would teach her manners someday!

Power struggles

Wild Seed comments on the dynamics of power through the conflict between its protagonists, Doro and Anyanwu. Doro and Anyanwu are both immortals with supernatural abilities, but represent very different worldviews. As a parasitical entity, Doro is a breeder, master, killer, and consumer of lives while, by being grounded in her body, Anyanwu is a nurturing “earth” mother, healer, and protector of life.[2][3]

Seemingly destined to become linked as implied by their names (Doro means “east” and Anyanwu means “sun”),[2] they engage in a clash of wills that lasts over a century. Some critics read their struggle as that between “masculine” and “feminine” perspectives with Doro as the patriarch who controls and dominates his people and Anyanwu as the matriarch who nurtures and protects her own.[4] Others see their relationship as resembling that of master and slave. Doro’s first assessment of Anyanwu, for example, is as valuable “wild seed,” whose genes will enhance his breeding experiments and so decides to “tame and breed her.” [3] This master/slave dynamic becomes complicated once Anyanwu refuses to be submissive to Doro’s requests and protects his people against him. Toward the end of the novel, Doro realizes he cannot bend Anyanwu’s will and, admitting her worth, he relents some of his absolute power in order to reconcile with her.[2][4]

Eugenics

He had to have the woman. She was wild seed of the best kind. She would strengthen any line he bred her into, strengthened it immeasurably.

In spite of its classification as fantasy fiction, Wild Seed has been considered as a major exponent of Butler’s interest in eugenics as a means to further human evolution. Butler herself characterized the novel as “more science fiction than most people realize” because Anyanwu’s shapeshifting and healing powers make her a medical expert.[5]

Maria Aline Ferreira goes further, describing both Doro and Anyanwu as “protogenetic engineers” whose deep understanding of how the human body functions help them remake themselves and transform others.[6]

For Andrew Schapper, Wild Seed is an entry point to the “ethics of controlled evolution” that permeate Butler’s novels, most obviously in the Xenogenesis trilogy. As an early novel on the subject, Wild Seed betrays Butler’s anxiety that eugenic manipulation and selective breeding could lead to an unethical abuse of power and thus she counters it with a “Judeo-Christian ethical approach to the sanctity of human life” represented by the character of Anyanwu.[7]

Gerry Canavan argues that Wild Seed challenges conventional fantasies of race by having Doro’s eugenics project supersede that of Europe’s by millenia. In this “alternate history,” “America itself--now transformed into a blip between the secret history of Doro's experiments and the brutal aftermath of their horrible success--becomes retold here as an African story, in an Africanist recentering of history that serves as a strongly anti-colonialist provocation, even if the results are mostly anti-utopian.” Still, while Doro’s eugenic project turns out a “superpowered blackness” that negates notions of white supremacy, his exploitation of his people as mere genetic experiments echoes the breeding methods of New World slave owners, thus replicating the actual history of racial slavery practiced by the Western world.[8]

Anyanwu as strong black female protagonist

Anyanwu had too much power. In spite of Doro’s fascination with her, his first inclination was to kill her. He was not in the habit of keeping alive people he could not control absolutely. (...) In her dolphin form, and before that in her leopard form, Doro had discovered that his mind could not find her.

As Butler scholar Ruth Salvaggio explains, Wild Seed was published at a time where strong black female protagonists were virtually nonexistent outside of Butler’s novels.[9] By creating the powerful character of Anyanwu, Butler's portrayal superseded stereotypes of women in the science fiction genre.[10] Lisbeth Gant-Britton describes Anyanwu as “a prime example of the kind of heroines Butler depicts. Strong-willed, physically capable, and usually endowed with some extra mental or emotional ability...they nonetheless must often endure brutally harsh conditions as they attempt to exercise some degree of agency.”[11]

Anyanwu's story is also a key contribution to women's literature in that it illustrates how women of color have survived both gender and racial oppression. As Elyce Rae Helford explains, "[b]y setting her novel in a realistic Africa and America of the past, [Butler] shows her readers the strength, the struggles, and the survival of black women through the slave years of United States history." [4]

Like many of Butler’s strong female African-American characters, Anyanwu is put in conflict with a male character, Doro, who is just as powerful as her. Butler uses this type of mis-match to display how differently males and females demonstrate their power and values.[2] Since Anyanwu’s way, J. Andrew Deman notes, “is the way of the healer” rather than of the killer,[10] she does not need violence to demonstrate her true strength or power. As Gant-Britton states, Anyanwu’s true power is shown many times during the story but it is definitely displayed when she threatens to commit suicide if Doro does not stop using her to create new species, making Doro submissive “to her will in the name of love,” if only for a moment.[11]

Wild Seed as alternative feminist narrative

Anyanwu wished she had gods to pray to, gods who would help her. But she had only herself and the magic she could perform with her own body.

Though published in 1980, Wild Seed diverts from the typical Second Wave “future utopia” narrative that had dominated the feminist science fiction of the 1960s and 1970s.[12] As L. Timmel Duchamp argues, Wild Seed as well as Kindred provided an alternative to the “white bourgeois narrative, premised on the notion of sovereign individualism” that feminist writers had been using as the prototype for their liberation stories. By not following the “all-or-nothing struggle” of Western fiction, Wild Seed better represented the hard compromises that real women must accept to live in a patriarchal, oppressive society.[3]

Control

Doro's character plays an important role in the novel because he has total control over all of the other characters. Part of the reason that Doro has so much control is because he determines whether one lives or dies. Doro has the gift and curse of being able to take on the body of anyone he desires. This is a gift because he is immortal, but it is a curse because when a body gets old, it is mandatory that he changes bodies in order to live. In order for Doro to survive, he must kill. This causes the other characters to be very wary of how they behave around Doro because they know that their life can be over at any moment. Another reason that Doro has so much control is because he is a man. The fact that he is a man makes it much easier for him to control other women, especially Anyanwu. Anyanwu is physically strong enough to fight Doro, but there are times where she does not retaliate against his physical abuse. Doro uses sex to draw women close to him and to create an emotional bond that makes it hard for them to leave.

Anyanwu as a representation of cyborg identity

Scholars view the shapeshifting Anyanwu as a fictional representation of Donna Haraway’s “cyborg” identity as defined in her 1985 essay “A Cyborg Manifesto.” Specifically, Anyanwu embodies Haraway’s “lived social and bodily realities in which people are not afraid of their joint kinship with animals and machines, not afraid of permanently partial identities and contradictory standpoints” as her shapeshifting abilities compete with Doro’s genetic engineering.[13][12] Anyanwu’s hybridity, her capability to represent multiple simultaneous identities, allows her to survive, to have agency, and to remain true to herself and her history in the midst of excruciating oppression and change.[12]

Stacy Alaimo further argues that Butler uses the “utterly embodied” Anyanwu not just to counteract Doro’s “horrific Cartesian subjectivity” but to actually transgress the dichotomy between mind and body, as Anyanwu is capable of “reading” other bodies with her own. As such, she illustrates Haraway’s concept of “situated knowledge,” wherein the subject (knower) does not distance itself from the object (known) and thus offers an alternative way of experiencing the world. Anyanwu’s body, then, is a “liminal space” that blurs traditional divisions of the world into “nature” and “culture.”[14]

For Gerry Canavan, Anyanwu’s obvious pleasure and joy in cannibalizing the Other into the Self (especially animals, and particularly, dolphins) presents us with an alternative to the cycle of violence and desire for power offered by the superhuman Patternists (and, by metaphoric extension, human history). Hers is a communion with Otherness that allows for an expansion of consciousness rather than the mere repetition of patterns of domination.[8]

Afrocentrism/Afrofuturism

At the time of its publication, Wild Seed was considered groundbreaking, as no other African viewpoint—nor African protagonist—existed in the science fiction genre. Butler’s novel is minimalistic in its West African backdrop, but nevertheless manages to convey the rich ethos of Onitsha culture through its Igbo heroine, Anyanwu.[15] In particular, Wild Seed is concerned with African kinship networks.[2]

In addition to its Afrocentric point of view, Wild Seed has also been classified as an Afrofuturistic text. As Elcye Rae Helford contends, the novel is part of Butler’s larger project to “depict the survival of African-American culture throughout history and into the future.”[4] Indeed, as the origin story of the Patternist series, which follows the exploits of a race of genetically-mutated black superhumans who eventually rule Earth in the 27th century, Wild Seed revises our sense of human history as directed by white supremacy.[8]

Commentary on New World slavery

Wild Seed represents and comments on the history of plantation slavery in the United States. Scenes in the novel depict the capture and sale of Africans; the character of European slave traders; the Middle Passage; and plantation life in the Americas.[16] Doro also resembles a slave master in that his program of forced reproduction aims to produce individuals who are exceptional at the cost of degrading the humanity of its participants.[8]

Additionally, the relation between the novel's two main characters, Anyanwu and Doro, may be said to comment on aspects of the slave trade. Anyanwu is coerced out of her home and transported to the Americas to breed offspring on Doro's behalf. Thus, Doro has been interpreted as symbolizing the control exercised over place and sexuality in the slave trade and Anyanwu as symbolizing the colonized and dominated native populations.[10] Anyanwu's conflicts with Doro also illustrate the emotional and psychological consequences of slavery and the possibilities of slave agency in Anyanwu's resistance to Doro's control.[4]

Animality

In Wild Seed, Butler portrays the distinction between animal and human as fluid. Anywanwu possesses the magical ability to transform into any animal she wishes, after she has tasted its flesh. Her entrance to the animal realm offers an escape from the violence and domination implicit in human social and sexual relations. For instance, after adopting a dolphin's form, the narrator observes, "She could remember being bullied as a female animal, being pursued by persistent males, but only in her true woman-shape could she remember being seriously hurt by males--men...Swimming with [the dolphins] was like being with another people. A friendly people. No slavers with brands and chains here. No Doro with gentle, terrible threats to her children, to her." [17]

Patriarchy and Western Modernity

In their initial encounter, Butler does the work of historicizing the past of both Doro and Anyanwu. Butler does this not as a medium to change the tides of history, but to ultimately work through the ways in which Western modernity employs racialization, as well as patriarchy, to build and maintain colonial projects.

The “history” of Doro’s reproductive colonies in which he calls “seed villages,” embodies the rationales of Western modernity. Doro also poses these “seed villages” as alternatives to Western modernity, more specifically slavery and colonization. As we see, the moment Anyanwu agrees to Doro’s continuation of his colonial project, she agrees to a patriarchal system of governance that controls not only her capacity to reproduce, but also whomever Doro chooses. This control of women’s reproduction is not dissimilar from the very same patriarchal governances of reproduction in slavery and colonization. After her agreeance, Doro and Anyanwu’s relationship is described in a master-slave/, colonizer/colonized dialectic. In this instance, colonization is linked to patriarchal desires, particularly those of control over reproduction.

Further it is the pleasure that Doro receives from breeding that reinscribes his role as a colonizer/master:

“…In the beginning he had gone after them for exactly the same reason wolves went for rabbits. In the beginning, he had bred them for exactly the same reason people bred rabbits…He was building a people who could die, did not know what enemies loneliness and boredom could be.”[18]

By describing the monstrosities of Doro’s colonial project as stemming from “natural” desires and human propensities, Octavia Butler, in Wild Seed, does the work of creating continuities between the patriarchal projects of the West and Doro’s creation of “seed villages.” Butler invokes the same pathos used to describe some of most infamous of colonizers/masters (i.e. Christopher Columbus) to rationalize Doro’s actions. It is the patriarchal desire in this moment that blurs the distinction between Western modernity and Doro’s project.

Post-Colonialism and Neo-Colonialism

Wild Seed subverts several characteristics of Postcolonialism. Postcolonialism suggests that the world has entered a period in which colonization is no longer a reality. It also suggests that colonization ended within the same time frame for both the colonized and the colonizers.[19] Doro is the embodiment of a colonizer. When Doro arrives to a seed village at the beginning of the novel he acknowledges that, "Slavers had been to it before him. With their guns and their greed, they had undone in a few hours the work of a thousand years." [20] Doro has colonized the world with his seed villages thousands of years before Europeans could do the same. Moreover, Doro still operates seed villages and still selectively breeds his people well into the 1800s. Therefore, "Wild Seed" illustrates that colonialism is an ongoing process that does not have a set beginning or ending.

Postcolonialist theory also suggests that anti-colonial and Third World nationalist movements do not exist in the post-colonial era.[19] Anyanwu is the metaphorical Third World in Butler's novel. She does not speak English when she first meets Doro, she maintains the traditions of her homeland, and she has no knowledge of advanced technology. Doro feels the need to civilize her when he brings her to the new world. He gets her to dress in new world styles and gets her to learn English and new world customs. Additionally, Doro uses her to breed children with supernatural powers. In the first half of the novel, Anyanwu is only useful to Doro because she can shape-shift and because her body can adapt to any poison and illness she subjects it to. In this way, Doro is exploiting her for her resources while forcing to act in a Western or "civilized" manner.

A characteristic of Neocolonialism is that Colonial powers continue to exploit the resources of their colonized counterpart for economic or political interests.[19] "Wild Seed" exhibits neocolonialism in the relationship between Doro and Anyanwu and the relationship between Doro and his descendants. Doro uses Anyanwu's children in order to continue his exploitation of her supernatural abilities. He notes that "Her children would hold her even if her husband did not." [21] Anyanwu does not want to endanger her children by attempting to escape or kill Doro. Even after she tries to start a new life on a plantation, he breeds with her to pass her supernatural abilities on to his children. He has a vested interest in her powers, and he refuses to let her go. Anyanwu's children face the same struggle when attempting to escape Doro. Doro threatens them with death in order to keep them under his control. He purposely creates villages for his people so that if they decide to leave they will be left with nothing. They rely on Doro for kinship and protection. In return, Doro uses them for his own gains.

Revision of origin stories

Scholars have noted that Wild Seed revisits a variety of myths. While most see Doro and Anyanwu’s creation of a new race as an Afrocentric revision of the Judeo-Christian story of Genesis,[22] Elizabeth A. Lynn and Andrew Schapper focus on the novel’s Promethean overtones,[23] with Lynn comparing it to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.[23] Finally, John R. Pfeiffer sees in Doro’s “ voracious... appetite for existence” a reference to the Faust myth and to vampire legends.[24]

Backgrounds

In an interview with Larry McCaffery and Jim McMenanin, Butler acknowledged that writing Wild Seed helped lighten her mood after finishing the grim fantasy that was her slave narrative Kindred.[25] She became interested in writing a novel about the Igbo (or Ibo) of Nigeria after reading the works of Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe.[2] Wild Seed involved a substantial amount of research because Butler had assumed that the Igbo were one people with one language, only to find that they communicated in five dialects [25]

Among the sources Butler consulted for the African background of her novel were The Ibo Word List, Richard N. Henderson’s The King in Every Man and Iris Andreski’s Old Wives Tales.[2] A mention in Henderson’s book to the Onitsha legend of Atagbusi, who was believed to be able to transform herself into large animals, became the basis for the character of Anyanwu.[22] As Butler told McCaffery and McMenanin,

- "Atagbusi was a shape-shifter who had spent her whole life helping her people, and when she died, a market gate was dedicated to her and later became a symbol of protection. I thought to myself, "This woman's description is perfect—who said she had to die?" [25]

In an interview with Rosalie G. Harrison, Butler revealed that making Anyanwu a healer came to her after witnessing a friend dying of cancer.[26]

The character of Doro, Butler revealed in a later interview with Randall Kenan, came from her own fantasies as an adolescent “to live forever and breed people.” And while she had already named him, she later discovered that his name in Nubian meant “the direction from which the sun comes” which worked well with her heroine’s Igbo name, Anyanwu, which means “the sun.” [5]

Butler scholar Sandra Y. Govan notes that Butler’s choice of an authentic African setting and characters was an unprecedented innovation in science fiction. She traces Butler’s West African backgrounds for Wild Seed to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Aye Armah’s 2000 Seasons, noting how the novel makes use of West African kinship networks to counteract the displacement of Africans during the Middle Passage and their dispersal once arrived in the New World.[2]

Reception

Wild Seed received many positive reviews, especially for its style, with the Washington Post’s Elizabeth A. Lynn praising Butler's writing as “spare and sure, and even in moments of great tension she never loses control over her pacing or over her sense of story.” [23] In his survey of Butler’s work, critic Burton Raffel singles out Wild Seed as an example of Butler’s “major fictive talent,” calling the book’s prose “precise and tautly cadence,” “forceful because it is focused” and “fictively superbly effective because it is in each and every detail true to the character’s lives.” In his 2001 book How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy, famed science-fiction writer Orson Scott Card used passages from Wild Seed’s opening paragraphs to illustrate principles of good fiction writing (e.g. how to properly name characters, how to keep the reader intrigued) as well as of good speculative writing (how abeyance, implication, and literalism may work together to produce fantastical realities that are nevertheless believable).[27]

Several reviewers also praised Butler’s expertise at conflating fantasy and realism, with Analog’s Tom Easton declaring that “Butler’s story, for all that it is fiction, rings true as only the best novels can.“ [28] Noting that “the story itself is eerily fascinating, and well-wrought,” Michael Bishop pinpointed that Butler’s greatest achievement was her creation of two immortal characters that are nevertheless completely believable as humans, making Wild Seed “one of the oddest love stories you are ever likely to read.” [15] Lynn also remarked that “[Butler’s] use of history as a backdrop to the struggles of her immortal protagonists provides a texture of realism that an imagined future, no matter how plausible, would have difficulty achieving.” [23] John Pfeiffer called it “probably Butler’s best novel…a combination of Butler’s brilliant fable and real history” and described Doro and Anyanwu as both “epic and authentic, engaging the reader’s awe or admiration or sympathy.” [16]

References

- ↑ ISFDB. "Publication Listing: Wild Seed." Internet Speculative Fiction Database. ISFDB Engine, n.d. Web.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Govan, Sandra Y. “Connections, Links, and Extended Networks: Patterns in Octavia Butler's Science Fiction”. Black American Literature Forum 18.2 (1984): 82–87.

- 1 2 3 Duchamp, L. Timmel. “‘Sun Woman’ or ‘Wild Seed’? How a Young Feminist Writer Found Alternatives to White Bourgeois Narrative Models in the Early Novels of Octavia Butler.” Ed. Rebecca J. Holden and Nisi Shawl. Strange Matings: Science Fiction, Feminism, African American Voices, and Octavia E. Butler. Seattle: Aqueduct Press, 2013. 82-95. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Helford, Elyce Rae. "Wild Seed". Masterplots II: Women’s Literature Series (1995): 1-3.

- 1 2 Kenan, Randall. “An Interview with Octavia E. Butler”. Callaloo 14.2 (1991): 495–504.

- ↑ Ferreira, Maria Aline. "Symbiotic Bodies and Evolutionary Tropes in the Work of Octavia Butler." Science Fiction Studies 37.3 (2010): 401-415.

- ↑ Schapper, Andrew. Eugenics, Genetic Determinism and the Desire for Racial Utopia in the Science Fiction of Octavia E. Butler. https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/41002

- ↑ Salvaggio, Ruth. “Octavia Butler and the Black Science-fiction Heroine”. Black American Literature Forum 18.2 (1984): 78–81. Web. 02 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 Deman, J. Andrew. "Taking out the Trash: Octavia E. Butler's Wild Seed and the Feminist Voice in American SF." FEMSPEC 6.2 (2005): 6-15.

- 1 2 Gant-Britton, Lisbeth. "Butler, Octavia (1947– )." African American Writers. Ed. Valerie Smith. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2001. 95-110.

- 1 2 3 Holden, Rebecca J. "'I Began Writing About Power Because I Had So Little': The Impact of Octavia Butler's Early Work on Feminist Science Fiction as a Whole (and On One Feminist Science Fiction Scholar in Particular." Ed. Rebecca J. Holden and Nisi Shawl. Strange Matings: Science Fiction, Feminism, African American Voices, and Octavia E. Butler. Seattle: Aqueduct Press, 2013. Print.

- ↑ Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In The Cyber cultures Reader. Eds. David Bell and Barbara M. Kennedy. London: Routledge, 2000. 291-324.

- ↑ Alaimo, Stacy. “Skin Dreaming”: The Bodily Transgressions of Fielding Burke, Octavia Butler, and Linda Hogan.” Ecofeminist Literary Criticism: Theory, Interpretation, Pedagogy. Ed. Greta C. Gaard and Patrick D. Murphy. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998. Print. 123-138.

- 1 2 Bishop, Michael. Rev. of Wild Seed, by Octavia Butler. Foundation 21 (1981): 86.

- 1 2 Pfeiffer, John R. "Butler, Octavia Estelle (b. 1947)." In Science Fiction Writers: Critical Studies of the Major Authors from the Early Nineteenth Century to the Present Day. Ed. Richard Bleiler. 2nd ed. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1999. 147-158. Gale Virtual Literature Collection.

- ↑ Butler, Octavia E. Wild Seed. New York: Warner Books, 1980. pg. 91.

- ↑ Butler, Octavia (2007). Seed to Harvest. Grand Central Publishing. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0446698900.

- 1 2 3 Shohat, Ella. "Notes on the 'Post-Colonial'". Social Text 31/32 (1992): 99-113.

- ↑ Butler, Octavia E. Wild Seed. New York: Warner Books, 1980. pg. 3.

- ↑ Butler, Octavia E. Wild Seed. New York: Warner Books, 1980. pg. 82.

- 1 2 Govan, Sandra Y. “Homage to Tradition: Octavia Butler Renovates the Historical Novel.” MELUS 13.1/2 (1986): 79–96. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/467226 >

- 1 2 3 4 Lynn, Elizabeth. A. “Vampires, Aliens and Dodos.” Washington Post. 28 September 1980. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/entertainment/books/1980/09/28/vampires-aliens-and-dodos/2d7b2f7c-5013-4bd1-b959-65f35fdbdb0a/>

- ↑ Pfeiffer, John R. "The Patternist Series." Magill’s Guide to Science Fiction & Fantasy Literature (1996): 1-3.

- 1 2 3 McCaffery, Larry and Jim McMenamin. “Interview with Octavia Butler.” Across the Wounded Galaxies: Interviews with Contemporary American Science Fiction Writers. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990. Print.

- ↑ Harrison, Rosalie G. “Sci-Fi Visions: An Interview with Octavia Butler.” In Butler, Octavia E., and Conseula Francis, ed. Conversations with Octavia Butler. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010. Print.

- ↑ Card, Orson Scott. How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy. Ohio: Writer's Digest Books, U.S, 2001. 90-100. Print.

- ↑ Easton, Tom. "Review of Wild Seed." Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact 150.1 (5 Jan. 1981): 168. Rpt. in Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Daniel G. Marowski and Roger Matuz. Vol. 38. Detroit: Gale, 1986.

Further reading

- Books to Look For, By Orson Scott Card, Fantasy & Science Fiction February (1990)

- Call, Lewis (2001), “Structures of Desire: Postanarchist Kink in the Speculative Fiction of Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany.” Anarchism & Sexuality: Ethics, Relationships and Power. Ed. Jamie Heckert & Richard Cleminson. Routledge, 131-153.

- Hampton, Gregory Jerome (2010), Changing Bodies in the Fiction of Octavia Butler: Slaves, Aliens, and Vampires. Lanham, MD : Lexington Books.

- Smith, Malaika Daneh (1994), "The African American Heroine in Octavia Butler's Wild Seed and Parable of the Sower." Thesis. U of California, Los Angeles

- Whiteside, Briana (2014), Octavia Butler’s Uncanny Women: Structure and Characters in The Patternist Series, Thesis

| ||||||||||||||||||||||