Contact angle

The contact angle is the angle, conventionally measured through the liquid, where a liquid–vapor interface meets a solid surface. It quantifies the wettability of a solid surface by a liquid via the Young equation. A given system of solid, liquid, and vapor at a given temperature and pressure has a unique equilibrium contact angle. However, in practice contact angle hysteresis is observed, ranging from the so-called advancing (maximal) contact angle to the receding (minimal) contact angle. The equilibrium contact is within those values, and can be calculated from them. The equilibrium contact angle reflects the relative strength of the liquid, solid, and vapor molecular interaction.

Thermodynamics

The shape of a liquid–vapor interface is determined by the Young–Laplace equation, with the contact angle playing the role of a boundary condition via Young's Equation.

The theoretical description of contact arises from the consideration of a thermodynamic equilibrium between the three phases: the liquid phase (L), the solid phase (S), and the gas or vapor phase (G) (which could be a mixture of ambient atmosphere and an equilibrium concentration of the liquid vapor). (The "gaseous" phase could be replaced by another immiscible liquid phase.) If the solid–vapor interfacial energy is denoted by  , the solid–liquid interfacial energy by

, the solid–liquid interfacial energy by  , and the liquid–vapor interfacial energy (i.e. the surface tension) by

, and the liquid–vapor interfacial energy (i.e. the surface tension) by  , then the equilibrium contact angle

, then the equilibrium contact angle  is determined from these quantities by Young's Equation:

is determined from these quantities by Young's Equation:

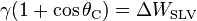

The contact angle can also be related to the work of adhesion via the Young–Dupré equation:

where  is the solid - liquid adhesion energy per unit area when in the medium V.

is the solid - liquid adhesion energy per unit area when in the medium V.

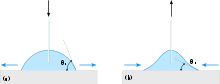

Hysteresis

If we add a small enough amount of liquid to a drop, the contact line will still be pinned, and the contact angle will increase. Similarly, if we remove a small enough amount of liquid from a drop, the contact line will still be pinned, and the contact angle will decrease. Hence, a drop placed on a surface has a spectrum of contact angles ranging from the so-called advancing (maximal) contact angle,  , to the so-called receding (minimal) contact angle,

, to the so-called receding (minimal) contact angle,  . The Young equilibrium contact angle is somewhere between those values, and the contact angle hysteresis is normally defined as

. The Young equilibrium contact angle is somewhere between those values, and the contact angle hysteresis is normally defined as  .

.

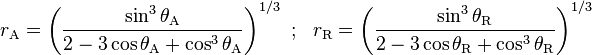

The Young equation assumes a perfectly flat surface. Even in such a smooth surface a drop will assume contact angle hysteresis. The equilibrium contact angle ( ) can be calculated from

) can be calculated from  and

and  as was shown theoretically by Tadmor [1] and confirmed experimentally by Chibowski [2] as,

as was shown theoretically by Tadmor [1] and confirmed experimentally by Chibowski [2] as,

where

On a surface that is rough or contaminated, there will also be contact angle hysteresis, but now the local equilibrium contact angle (the Young's equation is now only locally valid) may vary from place to place on the surface.[3] According to the Young–Dupré equation, this means that the adhesion energy varies locally – thus, the liquid has to overcome local energy barriers in order to wet the surface. One consequence of these barriers is contact angle hysteresis: the extent of wetting, and therefore the observed contact angle (averaged along the contact line), depend on whether the liquid is advancing or receding on the surface.

Because liquid advances over previously dry surface but recedes from previously wet surface, contact angle hysteresis can also arise if the solid has been altered due to its previous contact with the liquid (e.g., by a chemical reaction, or absorption). Such alterations, if slow, can also produce measurably time-dependent contact angles.

Dynamic Contact Angles

For liquid moving quickly over a surface, the contact angle can be altered from its value at rest. The advancing contact angle will increase with speed, and the receding contact angle will decrease.

Contact angle curvature

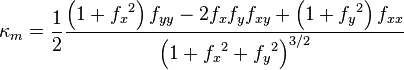

The Young–Laplace equation for a three-dimensional drop is highly non-linear. This is due to the mean curvature term which includes products of first- and second-order derivatives of the drop shape function  :

:

.

.

Solving this elliptic partial differential equation that governs the shape of a three-dimensional drop, in conjunction with appropriate boundary conditions, is extremely complicated, and an alternate energy minimization approach to this is generally adopted. The open-source software, Surface Evolver, which solves for the drop shape by minimizing the sum of potential and surface energies, has been used by many for this purpose. The shapes of three-dimensional sessile and pendant drops have been successfully predicted using this energy minimisation method.[4][5]

Typical contact angles

Contact angles are extremely sensitive to contamination; values reproducible to better than a few degrees are generally only obtained under laboratory conditions with purified liquids and very clean solid surfaces. If the liquid molecules are strongly attracted to the solid molecules then the liquid drop will completely spread out on the solid surface, corresponding to a contact angle of 0°. This is often the case for water on bare metallic or ceramic surfaces,[6] although the presence of an oxide layer or contaminants on the solid surface can significantly increase the contact angle. Generally, if the water contact angle is smaller than 90°, the solid surface is considered hydrophilic[7] and if the water contact angle is larger than 90°, the solid surface is considered hydrophobic. Many polymers exhibit hydrophobic surfaces. Highly hydrophobic surfaces made of low surface energy (e.g. fluorinated) materials may have water contact angles as high as ~120°.[6] Some materials with highly rough surfaces may have a water contact angle even greater than 150°, due to the presence of air pockets under the liquid drop. These are called superhydrophobic surfaces.

If the contact angle is measured through the gas instead of through the liquid, then it should be replaced by 180° minus their given value. Contact angles are equally applicable to the interface of two liquids, though they are more commonly measured in solid products such as non-stick pans and waterproof fabrics.

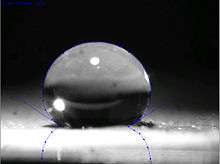

Image from a video contact angle device. Water drop on glass, with reflection below. |

A water drop on a lotus leaf surface showing contact angles of approximately 147°. |

Control of Contact Angles

Control of the wetting contact angle can often be achieved through the deposition or incorporation of various organic and inorganic molecules onto the surface. This is often achieved through the use of specialty silane chemicals which can form a SAM (self-assembled monolayers) layer. With the proper selection of the organic molecules with varying molecular structures and amounts of hydrocarbon and/or perfluoronated[8] terminations, the contact angle of the surface can tune. The deposition of these specialty silanes[9] can be achieved in the gas phase through the use of a specialized vacuum ovens or liquid-phase process. Molecules that can bind more perfluorinated terminations to the surface can results in lowering the surface energy (high water contact angle).

| Effect of Surface Fluorine on Contact Angle | Water Contact Angle (degs) |

|---|---|

| Precursor Name | on polished silicon |

| Henicosyl-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrododecyldimethyltris(dimethylaminosilane) | 118.0 |

| Heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrodecyltrichlorosilane - (FDTS) | 110.0 |

| Nonafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrohexyltris(dimethylamino)silane | 110.0 |

| 3,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6-Nonafluorohexyltrichlorosilane | 108.0 |

| Tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyltrichlorosilane - (FOTS) | 108.0 |

| BIS(Tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl)dimethylsiloxymethylchlorosilane | 107.0 |

| Dodecyltrichlorosilane – (DDTS) | 105.0 |

| Dimethyldichlorosilane - (DDMS) | 103.0 |

| 10-Undecenyltrichlorosilane - (V11) | 100.0 |

| Pentafluorophenylpropyltrichlorosilane | 90.0 |

Measuring methods

The static sessile drop method

The sessile drop contact angle is measured by a contact angle goniometer using an optical subsystem to capture the profile of a pure liquid on a solid substrate. The angle formed between the liquid–solid interface and the liquid–vapor interface is the contact angle. Older systems used a microscope optical system with a back light. Current-generation systems employ high resolution cameras and software to capture and analyze the contact angle. Angles measured in such a way are often quite close to advancing contact angles. Equilibrium contact angles can be obtained through the application of well defined vibrations.[10]

The pendant drop method

Measuring contact angles for pendant drops is much more complicated than for sessile drops due to the inherent unstable nature of inverted drops. This complexity is further amplified when one attempts to incline the surface. Experimental apparatus to measure pendant drop contact angles on inclined substrates has been developed recently.[5] This method allows for the deposition of multiple microdrops on the underside of a textured substrate, which can be imaged using a high resolution CCD camera. An automated system allows for tilting the substrate and analysing the images for the calculation of advancing and receding contact angles.

The dynamic sessile drop method

The dynamic sessile drop is similar to the static sessile drop but requires the drop to be modified. A common type of dynamic sessile drop study determines the largest contact angle possible without increasing its solid–liquid interfacial area by adding volume dynamically. This maximum angle is the advancing angle. Volume is removed to produce the smallest possible angle, the receding angle. The difference between the advancing and receding angle is the contact angle hysteresis.

Dynamic Wilhelmy method

A method for calculating average advancing and receding contact angles on solids of uniform geometry. Both sides of the solid must have the same properties. Wetting force on the solid is measured as the solid is immersed in or withdrawn from a liquid of known surface tension. Also in that case it is possible to measure the equilibrium contact angle by applying a very controlled vibration. That methodology, called VIECA, can be implemented in a quite simple way on every Wilhelmy balance.[11]

Single-fiber Wilhelmy method

Dynamic Wilhelmy method applied to single fibers to measure advancing and receding contact angles.

Washburn's equation capillary rise method

Enables measurement of average contact angle and sorption speed for powders and other porous materials. Change of weight as a function of time is measured.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Tadmor, Rafael (2004). "Line energy and the relation between advancing, receding, and Young contact angles". Langmuir 20 (18): 7659–64. doi:10.1021/la049410h. PMID 15323516.

- ↑ Chibowski, Emil (2008). "Surface free energy of sulfur—Revisited I. Yellow and orange samples solidified against glass surface". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 319: 505. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2007.10.059.

- ↑ de Gennes, P.G. (1985). "Wetting: statics and dynamics". Reviews of Modern Physics 57: 827–863. Bibcode:1985RvMP...57..827D. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.57.827.

- ↑ Y. Chen; B. He; J. Lee; N.A. Patankar (2005). "Anisotropy in the wetting of rough surfaces". Journal of colloid and interface science 281: 458–464.

- 1 2 G. Bhutani; K. Muralidhar; S. Khandekar (2013). "Determination of apparent contact angle and shape of a static pendant drop on a physically textured inclined surface". Interfacial Phenomena and Heat Transfer 1: 29–49.

- 1 2 Zisman, W.A. (1964). F. Fowkes, ed. Contact Angle, Wettability, and Adhesion. ACS. pp. 1–51.

- ↑ Renate Förch, Holger Schönherr, A. Tobias A. Jenkins (2009). Surface design: applications in bioscience and nanotechnology. Wiley-VCH. p. 471. ISBN 3-527-40789-8.

- ↑ http://insurftech.com/stiction/index.html

- ↑ B. Kobrin, T. Zhang, J, Chinn, "Choice of precursors in Vapor-phase Surface Modification", 209th Electrochemical Society meeting, May 7–12, 2006, Denver, CO

- ↑ C. Della Volpe; M. Brugnara (2006). "About the possibility of experimentally measuring an equilibrium contact angle and its theoretical and practical consequences". Contact Angle, Wettability and Adhesion 4: 79–100.

- ↑ C. Della Volpe; et al. (2001). "An experimental procedure to obtain the equilibrium contact angle from the Wilhelmy method". Oil and Gas Science and Technology 56: 9–22.

- ↑ Edward W. Washburn (1921). "The Dynamics of Capillary Flow". Physical Review 17 (3): 273. Bibcode:1921PhRv...17..273W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.17.273.

Further reading

- Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, Françoise Brochard-Wyart, David Quéré, Capillarity and Wetting Phenomena: Drops, Bubbles, Pearls, Waves, Springer (2004)

- Jacob Israelachvili, Intermolecular and Surface Forces, Academic Press (1985–2004)

- D.W. Van Krevelen, Properties of Polymers, 2nd revised edition, Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam-Oxford-New York (1976)

- Yuan, Yuehua; Lee, T. Randall (2013). "Contact Angle and Wetting Properties". Surface Science Techniques 51. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-34243-1. ISSN 0931-5195.

- Clegg, Carl Contact Angle Made Easy, ramé-hart (2013), ISBN 978-1-300-66298-3