West Coast Main Line

The West Coast Main Line (WCML) is a major inter-city railway route in the United Kingdom. It is Britain's most important rail backbone in terms of population served. The route links Greater London, the West Midlands, the North West, North Wales and the Central Belt of Scotland.

The WCML is the most important intercity rail passenger route in the United Kingdom, connecting the major cities of London, Coventry, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh which have a combined metropolitan population of over 24 million people. In addition, several sections of the WCML form part of the suburban railway systems in London, Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow, with many more smaller commuter stations, as well as providing a number of links to more rural towns. In 2008 the WCML handled 75 million passenger journeys.[3]

The WCML is also one of the busiest freight routes in Europe, carrying 43% of all UK rail freight traffic.[3] The line is the principal rail freight corridor linking the European mainland (via the Channel Tunnel) through London and South East England to the West Midlands, North West England and Scotland.[4] The line has been declared a strategic European route and designated a priority Trans-European Networks (TENS) route.

Since an upgrade in recent years, much of the line has a maximum speed of 125 mph (201 km/h), thereby meeting the European Union's definition of an upgraded high-speed line,[5] although only the Class 390 Pendolinos and Class 221 Super Voyagers operated by Virgin Trains are permitted to travel up to that speed, as they have tilting mechanisms and can travel through curves faster than conventional trains. Other traffic, including the Class 350s, are limited to 110 mph (177 km/h). The WCML has a significantly higher number of curves than most other main lines in Britain, hence the requirement for tilting operation for higher speeds.

Geography

Central to the WCML is its 399-mile (642 km)-long core section between London Euston and Glasgow Central[1] with principal InterCity stations at Warrington Bank Quay, Wigan, Preston, Lancaster, Oxenholme, Penrith and Carlisle. The length of the WCML's main core section is nominally quoted as being 401.25 miles (645.7 km). The basis of this measurement is taken as being the distance between the midpoint of Platform 18 of London Euston to that of Platform 1 of Glasgow Central, and has historically been the distance used in official calculations during speed record attempts.

The central core[6] has expanded into a complex system of branches and divergences serving also the major towns and cities of Northampton, Coventry, Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Stoke-on-Trent, Macclesfield, Stockport, Manchester, Runcorn, and Liverpool; there is also a link to Edinburgh, but this is not the direct route between London and Edinburgh.[7]

The WCML is not a single railway; rather it can be thought of as a network of routes which diverge and rejoin the central core between London and Glasgow. The route between Rugby and Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Stafford was the original main line until the shorter line was built in 1847 via the Trent Valley. South of Rugby there is a loop that serves Northampton, and there is also a branch north of Crewe to Liverpool which is notable since Weaver Junction on this branch is the oldest flyover-type junction in use. Among the other diversions are loops that branch off to serve Manchester, one between Colwich Junction in the Trent Valley south of Stafford via Stoke-on-Trent, one north of Stafford also via Stoke-on-Trent, and one via Crewe and Wilmslow. A further branch at Carstairs links Edinburgh to the WCML, providing a direct connection between the WCML and the East Coast Main Line.

Because of opposition by landowners along the route, in places some railway lines were built so that they avoided large estates and rural towns, and to reduce construction costs the railways followed natural contours, resulting in many curves and bends. The WCML also passes through some hilly areas, such as the Chilterns (Tring cutting), the Watford Gap and Northampton uplands followed by the Trent Valley, the mountains of Cumbria with a summit at Shap, and Beattock Summit in South Lanarkshire. This legacy of gradients and curves, and the fact that it was not originally conceived as a single trunk route, means the WCML was never ideal as a long-distance main line, with lower maximum speeds than the East Coast Main Line (ECML) route, the other major main line between London and Scotland.

In recent decades, the principal solution to the problem of the WCML's curvaceous line of route has been the adoption of tilting trains, formerly British Rail's APT, and latterly the Class 390 Pendolino trains constructed by Alstom and introduced by Virgin Trains in 2003. A 'conventional' attempt to raise line speeds as part of the InterCity 250 upgrade in the 1990s would have relaxed maximum cant levels on curves and seen some track realignments; this scheme faltered for lack of funding in the economic climate of the time.

History

Early history

The WCML was not originally conceived as a single trunk route, but was a number of separate lines built by different companies between the 1830s and the 1880s. After the completion of the successful Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830, schemes were mooted to build more inter-city lines. The business practice of the early railway era was for companies to promote individual lines between two destinations, rather than to plan grand networks of lines, as it was easier to obtain backing from investors. And so this is how the early stages of the WCML evolved.

The first stretch of what is now the WCML was the Grand Junction Railway connecting Liverpool and Manchester to Birmingham, via Crewe, Stafford and Wolverhampton opening in 1837. The following year the London and Birmingham Railway was completed, connecting to the capital via Coventry, Rugby and the Watford Gap. The Grand Junction and London and Birmingham railways shared a Birmingham terminus at Curzon Street station, so that it was now possible to travel by train between London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool[8][9]

These lines, together with the Trent Valley Railway (between Rugby and Stafford, avoiding Birmingham), and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway, (Crewe-Manchester), amalgamated operations in 1846 to form the London and North Western Railway (LNWR). Three other sections, the North Union Railway (Wigan-Preston), the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway and the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway were later absorbed by the LNWR.

North of Carlisle, the Caledonian Railway remained independent, and opened its main line from Carlisle to Beattock on 10 September 1847, connecting to Edinburgh in February 1848, and to Glasgow in November 1849.[10]

Another important section, the North Staffordshire Railway (NSR), which opened its route in 1848 from Macclesfield (connecting with the LNWR from Manchester) to Stafford and Colwich via Stoke-on-Trent also remained independent. Poor relations between the LNWR and the NSR meant that through trains did not run until 1867.[11]

The route to Scotland was marketed by the LNWR as 'The Premier Line'. Because the cross-border trains ran over the LNWR and Caledonian Railway, through trains consisted of jointly owned "West Coast Joint Stock" to simplify operations.[12] The first direct London to Glasgow trains in the 1850s took 12.5 hours to complete the 400-mile (640 km) journey.[13]

The final sections of what is now the WCML were put in place over the following decades by the LNWR. A direct branch to Liverpool, bypassing the earlier Liverpool and Manchester line was opened in 1869, from Weaver Junction north of Crewe to Ditton Junction via the Runcorn Railway Bridge over the River Mersey.[14]

To expand capacity, the line between London and Rugby was widened to four tracks in the 1870s. As part of this work, a new line, the Northampton Loop was built, opening in 1881, connecting Northampton before rejoining the main line at Rugby.[9]

The worst-ever rail accident in UK history, the Quintinshill rail disaster, occurred on the WCML during World War I, on 22 May 1915, between Glasgow Central and Carlisle, in which 227 were killed and 246 injured.

LMS era

The whole of the present route came under the control of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) on 1 January 1923 when railway companies were grouped, under the Railways Act 1921.

During the grouping era the LMS competed fiercely with the rival London and North Eastern Railway's East Coast Main Line for London to Scotland traffic (see Race to the North). Attempts were made to minimise end-to-end journey times for a small number of powerful lightweight trains that could be marketed as glamorous premium crack expresses, especially between London and Glasgow, such as the 1937–39 Coronation Scot, hauled by streamlined Princess Coronation Class locomotives, which made the journey in 6 hours 30 minutes,[15] making it competitive with the rival East Coast Flying Scotsman.

War-ravaged British Railways in the 1950s could not match this, but did achieve a London-Glasgow timing of 7 hours 15 minutes in the 1959–60 timetable by strictly limiting the number of coaches to eight and not stopping between London and Carlisle.[16]

British Rail era

In 1947, following nationalisation, the line came under the control of British Railways' London Midland and Scottish Regions, when the term "West Coast Main Line" came into use officially, although it had been used informally since at least 1912.[17] However, it is something of a misnomer as the line only physically touches the coast on a brief section overlooking Morecambe Bay between Lancaster and Carnforth for barely half a mile.

Modernisation by British Rail

Following the 1955 modernisation plan, the line was modernised and electrified in stages between 1959 and 1974. The first stretch to be electrified was Crewe to Manchester, completed on 12 September 1960. This was followed by Crewe to Liverpool, completed on 1 January 1962. Electrification was then extended southwards to London. The first electric trains from London ran on 12 November 1965, but full public service did not start until 18 April the following year. Electrification of the Birmingham line was completed on 6 March 1967. In March 1970 the government gave approval to electrification of the northern section between Weaver Junction (where the route to Liverpool diverges) and Glasgow, and this was completed on 6 May 1974.[6][18]

Once electrification was complete between London, the West Midlands and the North-West, a new set of high-speed long-distance services was introduced in 1966, launching British Rail's highly successful "Inter-City" brand[19] (the hyphen was later dropped) and offering such unprecedented journey times as London to Manchester or Liverpool in 2 hours 40 minutes (and even 2 hours 30 minutes for the twice-daily Manchester Pullman).[20] A significant new feature was that these fast trains were not just the occasional crack express but a regular-interval service throughout the day: hourly to Birmingham, two-hourly to Manchester, and so on.[21] With the completion of the northern electrification in 1974, London to Glasgow journey times were reduced to 5 hours.[6]

Along with electrification came the gradual introduction of modern coaches such as the Mark 2 and, following the northern electrification scheme's completion in 1974, the fully integral, air-conditioned Mark 3 design. These vehicles remained the mainstay of the WCML's express services until the early 2000s. Line speeds were raised to a maximum 110 mph (177 km/h), and these trains, hauled by powerful Class 86 and Class 87 electric locomotives, came to be seen as BR's flagship passenger product, immediately restoring the WCML to its premier position after a long period in the doldrums. Passenger traffic on the WCML doubled between 1962 and 1975.[22]

The modernisation also saw the demolition and redevelopment of several of the key stations on the line: BR was keen to symbolise the coming of the "electric age" by replacing the Victorian-era buildings with new structures built from glass and concrete. Notable examples were Birmingham New Street, Manchester Piccadilly, Stafford, Coventry and London Euston. To enable the latter, the famous Doric Arch portal into the original Philip Hardwick-designed terminus was demolished in 1962 amid much public outcry.[23] Recently, plans have been mooted to completely rebuild Euston station, with the reconstruction of Birmingham New Street nearing completion.

Electrification of the Edinburgh branch was carried out in the late 1980s as part of the East Coast Main Line electrification project in order to allow InterCity 225 sets to access Glasgow via Carstairs Junction.[24]

Modernisation brought great improvements, not least in speed and frequency, to many WCML services but there have been some losses over the years. Locations and lines served by through trains or through coaches from London but no longer so served are: Windermere; Barrow-in-Furness, Whitehaven and Workington; Huddersfield, Bradford Interchange, Leeds and Halifax (via Stockport); Blackpool South; Colne (via Stockport); Morecambe and Heysham; Southport (via Edge Hill); Blackburn and Stranraer Harbour. Notable also is the loss of through service between Liverpool and Scotland.

British Rail's proposal in the 1970s and 80s to introduce a tilting train to the curvaceous West Coast Main Line, did not occur as had been originally envisaged. The Advanced Passenger Train APT project succumbed to an insufficient political will in the United Kingdom to persist in solving the teething difficulties experienced with the many immature technologies necessary for a ground breaking project of this nature. The decision not to proceed was made against a backdrop of negative public perceptions shaped by media coverage of the time. However this train proved that London-Glasgow WCML journey times of less than 4 hours were achieveable and paved the way for the later tilting Virgin Pendolino trains.[25]

In the late 1980s, and in line with Japanese, French and German thinking of the time, British Rail put forward a track realignment scheme to raise speeds on the WCML; a proposed project called InterCity 250, which entailed realigning parts of the line in order to increase curve radii and smooth gradients in order to facilitate higher-speed running. The scheme which would have seen the introduction of new rolling stock derived from that developed for the East Coast electrification was scrapped in 1992, a victim of the recession of the period and the intervention of privatisation.

Modernisation by Network Rail

By the dawn of the 1990s, it was clear that further modernisation was required. Initially this took the form of the InterCity 250 project. But then the privatisation of BR intervened, under which Virgin Trains won a 15-year franchise in 1996 for the running of long-distance express services on the line. The modernisation plan unveiled by Virgin and the new infrastructure owner Railtrack involved the upgrade and renewal of the line to allow the use of tilting Pendolino trains with a maximum line speed of 140 mph (225 km/h), in place of the previous maximum of 110 mph (177 km/h). Railtrack estimated that this upgrade would cost £2 billion, be ready by 2005, and cut journey times to 1 hour for London to Birmingham and 1 hr 45 mins for London to Manchester.

However, these plans proved too ambitious and were subsequently aborted. Central to the implementation of the plan was the adoption of moving block signalling, which had never been proven on anything more than simple metro lines and light rail systems – not on a complex high-speed heavy-rail network such as the WCML. Despite this, Railtrack made what would prove to be the fatal mistake of not properly assessing the technical viability and cost of implementing moving block prior to promising the speed increase to Virgin and the government. By 1999, with little headway on the modernisation project made, it became apparent to engineers that the technology was not mature enough to be used on the line.[26] The bankruptcy of Railtrack in 2001 and its replacement by Network Rail following the Hatfield crash brought a reappraisal of the plans, while the cost of the upgrade soared. Following fears that cost overruns on the project would push the final price tag to £13 billion, the plans were scaled down, bringing the cost down to between £8 billion and £10 billion, to be ready by 2008, with a maximum speed for tilting trains of a more modest 125 mph (201 km/h) – equalling the speeds available on the East Coast route, but some way short of the original target, and even further behind BR's original vision of 155 mph (250 km/h) speeds planned and achieved with the APT.

The first phase of the upgrade, south of Manchester, opened on 27 September 2004 with journey times of 1 hour 21 minutes for London to Birmingham and 2 hours 6 minutes for London to Manchester. The final phase, introducing 125 mph (201 km/h) running along most of the line, was announced as opening on 12 December 2005, bringing the fastest journey between London and Glasgow to 4 hours 25 mins (down from 5 hours 10 minutes).[2] However, considerable work remained, such as the quadrupling of the track in the Trent Valley, upgrading the slow lines, the second phase of remodelling Nuneaton, and the remodelling of Stafford, Rugby, Milton Keynes and Coventry stations, and these were completed in late 2008. The upgrading of the Crewe-Manchester line via Wilmslow was completed in summer 2006.

In September 2006, a new speed record was set on the WCML – a Pendolino train completed the 401-mile (645 km) Glasgow Central – London Euston run in a record 3 hours 55 minutes, beating the APT's record of 4 hours 15 minutes, although the APT still holds the overall record on the northbound run.

The decade-long modernisation project was finally completed in December 2008.[27] This allowed Virgin's VHF (Very High Frequency) timetable to be progressively introduced through early 2009, the highlights of which are a three-trains-per-hour service to both Birmingham and Manchester during off-peak periods, and nearly all Anglo-Scottish timings brought under the 4 hours 30 minutes barrier – with one service (calling only at Preston) achieving a London-Glasgow time of 4 hours 8 minutes.

Infrastructure

Track

The main spine of the WCML is quadruple track almost all of the way from London to Crewe (where the line diverges into sections to Manchester, North Wales, Liverpool, and Scotland)[3] The remaining sections are mainly double track, except for a few busy sections around Glasgow, Manchester and Liverpool.

The complete route has been cleared for W10 loading gauge freight traffic, allowing use of higher 9 ft 6 in (2,896 mm) hi-cube shipping containers.[28][29]

Electrification

Nearly all of the WCML is electrified with overhead wires at 25 kV AC.[30] Several of the remaining unelectrified branches of the WCML in the North West are scheduled to be electrified by 2016 such as the Liverpool to Wigan, Manchester to Preston and Preston to Blackpool branches.[31]

Rolling stock

The majority of stock used on the West Coast Main Line is new-build, part of Virgin's initial franchise agreement having been a commitment to introduce a brand-new fleet of tilting Class 390 "Pendolino" trains for long-distance high-speed WCML services. The 53-strong Pendolino fleet, plus three tilting SuperVoyager diesel sets, were bought for use on these InterCity services. One Pendolino was written off in 2007 following the Grayrigg derailment. After the 2007 franchise "shake-up" in the Midlands, more SuperVoyagers were transferred to Virgin West Coast, instead of going to the new CrossCountry franchise. The SuperVoyagers are used on London-Chester and Holyhead services because the Chester/North Wales line is not electrified, so they run "under the wires" between London and Crewe. SuperVoyagers were also used on Virgin's London-Scotland via Birmingham services, even though this route is entirely electrified – this situation is however changing since the expansion of the Pendolino fleet; from 2013 onward Class 390 sets are now routinely deployed on Edinburgh/Glasgow-Birmingham services.

By 2012, the WCML Pendolino fleet will be strengthened by the addition of two coaches to 31 of the 52 existing sets, thus turning them into 11-car trains. Four brand new 11-car sets are also part of this order, one of which will replace the set lost in the Grayrigg derailment. Although the new stock is to be supplied in Virgin livery, it was not expected to enter traffic before 31 March 2012, when the InterCity West Coast franchise was due to be re-let, though the date for the new franchise was later put back to December 2012,[32] and any effect of this on the timetable for introducing the new coaches remains unclear.

Previous franchisees Central Trains and Silverlink (operating local and regional services partly over sections of the WCML) were given 30 new "Desiros", originally ordered for services in the south-east. Following Govia's successful bid for the West Midlands franchise in 2007, another 37 Desiros were ordered to replace its older fleet of 321s.

The older BR-vintage locomotive-hauled passenger rolling stock still has a limited role on the WCML, with the overnight Caledonian Sleeper services between London Euston and Scotland using Mark 3 and Mark 2 coaches. Virgin has also retained and refurbished one of the original Mark 3 rakes with a Driving Van Trailer and a Class 90 locomotive as a standby set to cover for Pendolino breakdowns. This set was retired from service on 25 October with a rail tour the following day. In November 2014 the "Pretendolino" was transferred to Norwich Crown Point depot to enter service with Abellio Greater Anglia having come to the end of its agreed lease to Virgin Trains.

The following table lists the rolling stock which forms the core passenger service pattern on the WCML serving its principal termini; it is not exhaustive since many other types use sections of the WCML network as part of other routes – notable examples include the InterCity 125 HST on certain CrossCountry services (primarily through the West Midlands area) and the Virgin Trains East Coast InterCity 225 between Edinburgh and Glasgow Central.

| Class | Image | Type | Cars per set | Top speed | Number | Operator | Routes | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||||||

| Class 390 Pendolino |  |

EMU | 9 or 11 | 140 (limited to 125) | 225 (limited to 200) | 56 | Virgin Trains | Services from London Euston to Manchester, Liverpool, West Midlands, Glasgow and Edinburgh. | 2001–2004 2009–2012 |

| Class 221 SuperVoyager |  |

DEMU | 5 | 125 | 200 | 20 | Virgin Trains | Services between London Euston to: North Wales, Chester, Shrewsbury and Blackpool. Selected London Euston to Glasgow/Edinburgh via Birmingham services. Selected services between London Euston to the West Midlands |

2001–2002 |

| Class 92 |  |

Electric locomotive | 1 | 87 | 140 | 6 | Caledonian Sleeper (x6) Hired from GB Railfreight |

All Caledonian Sleeper services between London Euston as far as Glasgow & Edinburgh | 1993–1996 |

| Mark 2 Coach |  |

Lounge car Seated Sleeper |

6 | 100 | 161 | 22 | Caledonian Sleeper | All Caledonian Sleeper services between London Euston to Scottish destinations | 1971–1974 |

| Mark 3 Coach |  |

Sleeping car | 10–12 | 125 (limited to 80 in service) | 200 (130 in service) | 53 | Caledonian Sleeper | All Caledonian Sleeper services between London Euston to Scottish destinations | 1980–1982 |

| Class 319 |  |

EMU | 4 | 100 | 160 | 4 | London Midland | Peak hour West Coast Main Line services | 1987-1988 |

| Class 350/1 Desiro |  |

EMU | 4 | 110 | 180 | 30 | London Midland | London Euston to Tring, Milton Keynes, Northampton and Birmingham Birmingham to Liverpool. |

2004–2005 |

| Class 350/2 Desiro |  |

EMU | 4 | 100 | 160 | 37 | London Midland | London Euston to Tring, Milton Keynes, Northampton, Crewe and Birmingham Birmingham to Liverpool. |

2008–2009 |

| Class 350/3 Desiro | .jpg) |

EMU | 4 | 110 | 177 | 10 | London Midland | London Euston to Tring, Milton Keynes, Northampton, Crewe and Birmingham Birmingham to Liverpool. |

2014 |

| Class 350/4 Desiro | .jpg) |

EMU | 4 | 110 | 180 | 10 | First TransPennine Express | Manchester Airport to Glasgow and Edinburgh. | 2013–2014 |

| Class 185 Pennine |  |

DMU | 3 | 100 | 160 | 51 | First TransPennine Express | TransPennine North West | 2005–2006 |

| Class 377/2 Electrostar | EMU | 4 | 100 | 160 | 12 | Southern | Milton Keynes Central to South Croydon | 2003–2004 | |

| Class 377/7 Electrostar | EMU | 5 | 100 | 160 | 8 | Southern | Milton Keynes Central to South Croydon | 2013–14 | |

Operators

Virgin Trains (West Coast)

The current principal train operating company on the West Coast Main Line is Virgin Trains, which runs the majority of long-distance services under the InterCity West Coast rail franchise. During 2011–2012 the Department for Transport conducted a franchise competition for the InterCity West Coast franchise, announcing that FirstGroup had been awarded the new franchise, but then cancelled the competition, before any contracts were signed. Subsequently, the contract for Virgin Trains to operate the InterCity West Coast franchise has been extended by between 9 and 13 months, while a competition for a new interim franchise agreement is run.[33]

Virgin operates nine trains per hour on the WCML from London Euston, with three trains per hour to Manchester, two each hour to Birmingham, one train per hour to each of Chester, Liverpool and Glasgow, five trains on a weekday to Holyhead and three trains on a weekday to Bangor. There is also one weekday train in to/from Wrexham General. Additional peak terminating services run between London Euston and Rugby, Preston, Wolverhampton, Crewe, Birmingham International, Lancaster and Carlisle. Virgin also operates a service between Edinburgh or Glasgow and Euston via Birmingham over the WCML once every two hours, with additional trains during the early morning, late evening, rush hour and night that terminate or start at Birmingham. From December 2014, Virgin Trains have also introduced two daily services between London Euston and Shrewsbury and one daily (Monday to Friday) service between London Euston and Blackpool North.

Average Journey Times from London Euston[34]

| Destination | Fastest journey time | Average journey time | Distance[35] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rugby | 0h47' | 1h14' | 82.5 miles (132.8 km) |

| Birmingham International | 1h09' | 1h10' | 104.5 miles (168.2 km) |

| Birmingham New Street | 1h12' | 1h23' | 113 miles (182 km) |

| Manchester Piccadilly | 1h58' | 2h09' | 184.25 miles (296.52 km) |

| Liverpool Lime Street | 2h01' | 2h08' | 193.5 miles (311.4 km) |

| Chester | 1h58' | 2h02' | 179 miles (288 km) |

| Holyhead | 3h40' | 3h46' | 263.5 miles (424.1 km) |

| Wrexham General | 2h16' | 2h28' | 191 miles (307 km) |

| Preston | 2h00' | 2h18' | 209 miles (336 km) |

| Lancaster | 2h30' | 2h34' | 230 miles (370 km) |

| Carlisle | 3h13' | 3h15' | 299 miles (481 km) |

| Glasgow Central | 4h08' | 4h31' | 401.25 miles (645.75 km) |

London Midland

London Midland provides commuter and long-distance services on the route, which terminate at London Euston. They are all operated under the "Express" brand. There are two trains an hour from London to Birmingham; one calling at the majority of stations en route and one calling only at Watford Junction, Milton Keynes Central, Northampton, Rugby, Coventry, Tile Hill, Hampton-in-Arden, Birmingham International and Marston Green. There are three trains per hour from Birmingham New Street to London Euston. These London-Birmingham stopping services are roughly one hour slower, end to end, than the Virgin Trains fast service. There is also an hourly service from London Euston to Northampton calling at Leighton Buzzard, Bletchley, Milton Keynes Central and Wolverton.

London Midland also operates an hourly service between London and Crewe, serving Milton Keynes Central, Rugby, Nuneaton, Atherstone, Tamworth, Lichfield Trent Valley, Rugeley Trent Valley, Stafford, Stone, Stoke-on-Trent, Alsager and Crewe. This service was introduced in 2008 to coincide with the withdrawal of the similar Virgin Trains service. Under 'Project 110' this service was reconfigured in December 2012 and to operate 10 mph faster using enhanced British Rail Class 350/1 units.

A service to Tring is provided half-hourly from Euston; one calling at Harrow & Wealdstone, Bushey, Watford Junction, Kings Langley, Apsley, Hemel Hempstead and Berkhamsted and one calling at Wembley Central, Harrow & Wealdstone, Bushey, Watford Junction, Kings Langley, Apsley, Hemel Hempstead and Berkhamstead. An hourly service operates to Milton Keynes Central calling at Watford Junction, Hemel Hempstead, Berkhamstead, Tring, Cheddington, Leighton Buzzard and Bletchley.

During peak periods London Midland offers "The Watford Shuttle", which operates between Euston and Watford Junction.

London Midland also operates an hourly stopping train on the Marston Vale Line from Bletchley to Bedford as well as a 45-minute service on the Abbey Line to St Albans. These are both local branches off the WCML.

After the Central Trains franchise was revised, London Midland took over services running on the WCML between Birmingham and Liverpool.

First TransPennine Express

As part of its North West route, First TransPennine Express provides services along the WCML between Manchester Airport and Glasgow/Edinburgh (alternating serving each every 2 hours) as part of its Manchester Airport to Scotland service. Also as part of its North West route, services run between Preston and Manchester branches off the WCML encompassing Blackpool North, Windermere and Barrow-in-Furness.

Southern

Southern provide an hourly service between South Croydon and Milton Keynes Central, which calls at all stations then Clapham Junction via Selhurst, then all stations on the West London Line then Shepherd's Bush, Wembley Central, Harrow & Wealdstone, Watford Junction, Hemel Hempstead, Berkhamsted, Tring, Leighton Buzzard, Bletchley and Milton Keynes Central.

Virgin Trains East Coast

Virgin Trains East Coast operates one train per day between Glasgow Central and London Kings Cross via Edinburgh Waverley,[36] operating over the West Coast Main Line route between Edinburgh and Glasgow.

CrossCountry

CrossCountry operates services from Plymouth, Bournemouth and Bristol Temple Meads to Manchester Piccadilly; these trains run also the West Coast Main Line between Coventry and Manchester Piccadilly. Some trains from Manchester Piccadilly to Bristol Temple Meads are extended to Paignton and Plymouth, and on summer weekends to Penzance and Newquay. CrossCountry services between Reading and Newcastle also use a small portion of the West Coast Main Line between Coventry and Birmingham New Street. Services towards Reading are often extended to Southampton Central (or occasionally Bournemouth) and 1 train per day towards Reading is extended to Guildford.

CrossCountry also operates a 2 hourly service to/from Glasgow Central, which operates to either Penzance, Plymouth, Newcastle upon Tyne, Bristol Temple Meads or Birmingham New Street. On summer weekends trains from Glasgow Central also operate to Paignton, Penzance and Newquay. These services use the West Coast Main Line from Edinburgh to Glasgow Central.

Current developments

Felixstowe and Nuneaton freight capacity scheme

A number of items of work are under way or proposed to accommodate additional freight traffic between the Haven ports and the Midlands including track dualling. The 'Nuneaton North Chord' was completed and opened on 15 November 2012.[37][38] The chord will ease access for some trains between the Birmingham to Peterborough Line and the WCML. The Ipswich chord was opened at the end of March 2014 allowing trains to run without reversing from Felixstowe towards the Midlands.[39]

Stafford Area Improvements Programme

Planned flying junction and 2.5 mi (4.0 km) track diversion in the Stafford – Norton Bridge area. This will replace the current level junction where the Stafford to Manchester via Stoke-on-Trent line diverges from the trunk route at Norton Bridge, avoiding conflicting train movements to enhance capacity and reduce journey times, additional freight capacity will also be provided around Stafford station. There will be two extra off-peak trains per hour from Euston to the North West, one extra train per hour from Manchester to Birmingham and one additional freight train per hour. The resignalling work associated with this project is due to be completed in summer 2015 and the Norton Bridge work will complete in December 2016, followed by a new timetable introduced in December 2017.[40]

Proposed development

Increased line speed

Virgin Trains put forward plans in 2007 to increase the line speed in places on the WCML – particularly along sections of the Trent Valley Line between Stafford and Rugby from 125 to 135 mph (200 to 217 km/h) after the quadrupling of track had been completed. This would permit faster services and possibly allow additional train paths. 135 mph (217 km/h) was claimed to be achievable by Pendolino trains while using existing lineside signalling without the need for cab signalling via the use of the TASS system (Tilt Authorisation and Speed Supervision) to prevent overspeeding. In practice regulations introduced by the HMRI (now ORR) at the time of the ECML high-speed test runs in 1991 are still in force prohibiting this. Network Rail was aware of Virgin Train's aspirations;[42] however, on 4 November 2009 Chris Mole MP (then Parliamentary Under Secretary of State, Transport) announced that there were no plans for this to happen and thus for the foreseeable future the maximum speed will remain at 125 mph (201 km/h).[43]

In promoting this proposal, Virgin Trains reported that passenger numbers on Virgin West Coast increased from 13.6 million in 1997/98 to 18.7 million in 2005/6, while numbers on CrossCountry grew from 12.6 million to 20.4 million over the same period.[44]

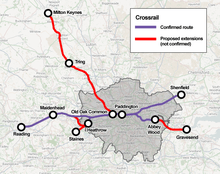

Crossrail extension

In the London & South East Rail Utilisation Strategy (RUS) document published by Network Rail in 2011, a proposal was put forward to extend the Crossrail lines now currently under construction in central London along the West Coast Main Line as far as Tring and Milton Keynes Central. The scheme would involve the construction of a tunnel in the vicinity of the proposed new station at Old Oak Common in West London connecting the Crossrail route to the WCML slow lines with a potential for interchange with the planned High Speed 2 line. Under current plans, a proportion of westbound Crossrail trains will terminate at Paddington due to capacity limitations; the RUS recommends the WCML extension as it will enable these services to continue beyond Paddington, maximising the use of the central London tunnels. The RUS also notes that diversion of WCML regional rail services via Crossrail into central London would alleviate congestion at Euston station, and consequently reduce the need for infrastructure work on the London Underground network which would be required to accommodate HS2 passengers arriving at Euston. The Crossrail extension proposal has not been officially confirmed or funded.[41] In August 2014, the government launched a study into the Crossrail extension.[45]

Accidents

- Grayrigg derailment (at Lambrigg Crossovers, south of Grayrigg) – 23 February 2007; 1 killed

- Tebay rail accident – 15 February 2004; 4 workers killed (no public involvement)

- Norton Bridge rail crash – 16 October 2003; 1 injured

- Winsford rail crash – 23 June 1999; 31 injured

- Watford rail crash – 8 August 1996; 1 killed, 69 injured

- Stafford rail crash (1996) – 8 March 1996; 1 killed, 22 injured

- Newton rail crash – 21 July 1991; 4 killed; 22 injured

- Stafford rail crash (1990) – 4 August 1990; 1 killed, 35 injured

- Colwich rail crash – 19 September 1986; 1 killed 60 injured

- Wembley Central rail crash – 11 October 1984; 3 killed, 18 injured

- Nuneaton rail crash – 6 June 1975; 6 killed 67 injured

- Watford Junction rail crash – 1975; 1 killed, 11 injured

- Hixon – 6 January 1968; 11 killed, 27 injured

- Stechford rail crash – 28 February 1967; 9 killed, 16 injured

- Cheadle Hulme – 28 May 1964; 3 killed

- Coppenhall Junction – 26 December 1962; 18 killed, 34 injured

- Harrow and Wealdstone – 8 October 1952; 112 killed, 340 injured – worst accident in England and London.

- Weedon (1951); – 21 September 1951; 15 killed, 36 injured

- Lambrigg Crossing signal box between Grayrigg and Oxenholme – 18 May 1947 (express hit light engine through driver missing a signal while looking in his food box); 4 in hospital, 34 minor injuries[46]

- Lichfield – 1 January 1946; 20 killed, 21 injured.

- Bourne End rail crash – 30 September 1945; 43 killed, 64 injured

- Winwick Junction – 28 September 1934; 12 killed

- Weedon (1915); 14 August 1915; 10 killed, 21 injured

- Quintinshill rail crash – 22 May 1915; 227 killed, 246 injured. – worst ever rail accident in the United Kingdom.

- Ditton Junction rail crash; 17 September 1912; 15 killed

- Chelford rail accident; 22 December 1894; 14 killed, 48 injured

- Wigan rail crash – 1 August 1873; 13 killed, 30 major injuries.

- Tamworth rail crash – 14 September 1870; 3 killed, 13 injured.

- Warrington rail crash – 29 June 1867; 8 killed, 33 injured

- Atherstone rail accident – 16 November 1860; 10 killed.

The route in detail

Network Rail, successor from 2001 to Railtrack plc, in its business plan published in April 2006,[42] has divided the national network into 26 'Routes' for planning, maintenance and operational purposes.[47] Route 18 is named as 'that part of the West Coast Main Line that runs between London Euston and Carstairs Junction' although it also includes several branch lines that had not previously been considered part of the WCML.[48] The northern terminal sections of the WCML are reached by Routes 26 (to Motherwell and Glasgow) and 24 (to Edinburgh). This therefore differs from the "classic" definition of the WCML as the direct route between London Euston and Glasgow Central.

The cities and towns served by the WCML are listed in the tables below. Stations on loops and branches are marked **. Those stations in italics are not served by main-line services run by Virgin Trains but only by local trains. Between Euston and Watford Junction the WCML is largely but not exactly paralleled by the operationally independent Watford DC Line, a local stopping service now part of London Overground, with 17 intermediate stations, including three with additional platforms on the WCML.

The final table retraces the route specifically to indicate the many loops, branches, junctions and interchange stations on Route 18, which is the core of the WCML, with the new 'Route' names for connecting lines.

The North Wales Coast Line between Crewe and Holyhead and the line between Manchester and Preston are not electrified. Services between London and Holyhead and those between Manchester and Scotland are mostly operated either by Super Voyager tilting diesel trains or, in the case of one of the Holyhead services, by a Pendolino set hauled from Crewe by a Class 57/3 diesel locomotive.

London to Glasgow and Edinburgh (Network Rail Route 18)

| Town/City | Station | Ordnance Survey National Grid Reference |

Branches and loops |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | London Euston | TQ295827 | |

| Wembley | Wembley Central | TQ182850 | |

| Harrow | Harrow and Wealdstone | TQ154894 | |

| Bushey | Bushey | TQ118953 | |

| Watford | Watford Junction | TQ109973 | |

| Apsley | Apsley | TL080019 | |

| Kings Langley | Kings Langley | TL062048 | |

| Hemel Hempstead | Hemel Hempstead | TL042059 | |

| Berkhamsted | Berkhamsted | SP993081 | |

| Tring | Tring | SP950122 | |

| Cheddington | Cheddington | SP922185 | |

| Leighton Buzzard | Leighton Buzzard | SP910250 | |

| Milton Keynes (Bletchley area) | Bletchley | SP868337 | |

| ** Bedford | ** Bedford | TL042497 | Marston Vale Line spur |

| Milton Keynes (centre) | Milton Keynes Central | SP841380 | |

| Milton Keynes (at Wolverton area | Wolverton | SP820414 | |

| ** Northampton | ** Northampton | SP623666 | Northampton Loop diverges north of Wolverton |

| ** Long Buckby | ** Long Buckby | SP511759 | Northampton Loop rejoins south of Rugby |

| Rugby | Rugby | SP511759 | Rugby-Birmingham-Wolverhampton-Stafford (see separate table below) |

| Nuneaton | Nuneaton | SP364921 | |

| Atherstone | Atherstone | SP304979 | |

| Polesworth | Polesworth | SK264031 | |

| Tamworth | Tamworth | SK213044 | |

| Lichfield | Lichfield Trent Valley | SK136099 | |

| Rugeley | Rugeley Trent Valley | SK048191 | |

| Stafford | Stafford | SJ918229 | Rugby-Birmingham-Stafford rejoins Manchester via Stoke-on-Trent diverges either before or after Stafford (two routes) |

| ** Stoke-on-Trent | ** Stoke-on-Trent | SJ879456 | |

| ** Congleton | ** Congleton | SJ872623 | |

| ** Macclesfield | ** Macclesfield | SJ919736 | |

| ** Stockport | ** Stockport | SJ892898 | |

| ** Manchester | ** Manchester Piccadilly | SJ849977 | |

| Crewe | Crewe | SJ711546 | Crewe-Manchester-Preston and Crewe-Chester-North Wales-Holyhead (see separate tables below) |

| Winsford | Winsford | SJ670660 | |

| Northwich | Hartford | SJ631717 | |

| Acton Bridge | Acton Bridge | SJ598745 | Liverpool route diverges north of Acton Bridge |

| ** Runcorn | ** Runcorn | SJ508826 | |

| ** Liverpool | ** Liverpool Lime Street | SJ352905 | |

| Warrington | Warrington Bank Quay | SJ599878 | Earlestown & Newton Loop diverges at Winwick Junction, rejoining at Golborne Junction |

| Wigan | Wigan North Western | SD581053 | |

| Preston | Preston | SD534290 | Crewe-Manchester-Preston rejoins |

| Lancaster | Lancaster | SD471617 | |

| Oxenholme (Kendal) | Oxenholme Lake District | SD531901 | |

| Penrith | Penrith | NY511299 | |

| Carlisle | Carlisle | NY402554 | |

| Lockerbie | Lockerbie | NY137817 | |

| Carstairs | Carstairs Junction | NS952454 | |

| Then either | |||

| Motherwell | Motherwell | NS750572 | |

| Glasgow | Glasgow Central | NS587651 | |

| or | |||

| Edinburgh (Haymarket/West End) | Haymarket | NT239731 | |

| Edinburgh | Edinburgh Waverley | NT257738 |

Branches and loops

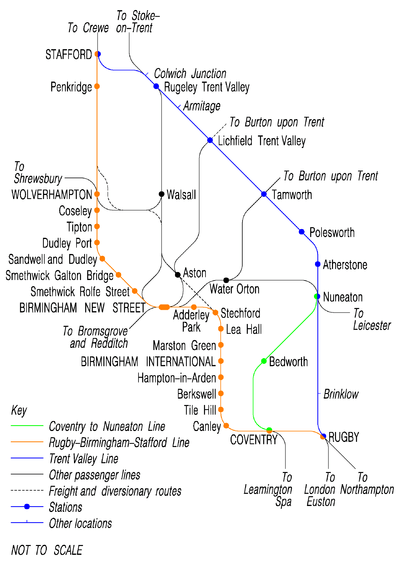

The WCML is noted for the diversity of branches served between the London and Glasgow main line. The following map deals with the very complex network of lines in the West Midlands that link the old route via Birmingham with the new WCML route via the Trent Valley (i.e. 1830s versus 1840s):

In the following tables, related to the WCML branches, only the Intercity stations are recorded:

Rugby-Birmingham-Wolverhampton-Stafford (Network Rail Route 17)

| Town/City | Station | Ordnance Survey grid reference |

|---|---|---|

Crewe-Holyhead and Chester-Wrexham (Network Rail Route 22)

| Town/City | Station | Ordnance Survey grid reference |

|---|---|---|

|

Crewe-Manchester-Preston (Network Rail Route 20)

| Town/City | Station | Ordnance Survey grid reference |

|---|---|---|

Network Rail Route 18 (WCML) – Branches and junctions

| Location | Type | Route | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camden Jnct | Branch | 18 | Watford DC Line (WDCL) |

| + | Junction | 6 | North London Line from Primrose Hill joins WDCL and WCML |

| Willesden Jnct | Junction | 6 | North London Line from West Hampstead joins WDCL and WCML |

| + | Junction | 2 | West London Line from Clapham Junction joins WCML |

| + | Junction | 6 | North London Line from Richmond joins WCML |

| Willesden Junction | Interchange | 6 | North London Line with Watford DC Line |

| Watford Junction | Branch | 18 | Watford DC Line terminates at separate bay platforms |

| + | Branch | 18 | St Albans Branch Line (AC single line single section) to St Albans |

| Bletchley | Branch | 18 | Marston Vale Line to Bedford |

| Bletchley High Level (Denbigh Hall South Jnct) | Branch | 16 | Freight only line to Newton Longville (remnant of mothballed Varsity Line to Oxford) |

| Hanslope Junction | Loop | 18 | Northampton Loop leaves a few miles north of Wolverton and rejoins just south of Rugby |

| Rugby | Junction | 17 | West Midlands Main Line to Coventry, Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Stafford |

| Nuneaton | Junction | 19 | The Birmingham to Peterborough Line from Peterborough |

| + | Junction | 17 | The Coventry to Nuneaton Line |

| + | Junction | 17 | The Birmingham to Peterborough Line to Birmingham |

| Tamworth | Interchange | 17 | The Cross Country Route (MR) Bristol and Birmingham to Derby and the North East |

| Lichfield Trent Valley | Interchange | 17 | The Cross-City Line Redditch to Lichfield |

| + | Junction | 17 | north of the station |

| Rugeley Trent Valley | Junction | 17 | The Chase Line from Birmingham to Rugeley |

| Colwich Junction | Branch | 18 | to Stoke-on-Trent and Manchester (Route 20 from Cheadle Hulme) |

| Stafford | Junction | 17 | West Midlands Main Line from Coventry, Birmingham and Wolverhampton |

| Norton Bridge | Branch | 18 | to Stone to join line from Colwich Jnct to Manchester (Route 20 from Cheadle Hulme) |

| Stoke-on-Trent | Junction | 19 | from Derby |

| Kidsgrove | Branch | 18 | to Alsager and Crewe |

| Cheadle Hulme | – | 20 | Route 18 London – Manchester Line becomes Route 20 through to Manchester |

| Crewe | Branch | 18 | from Kidsgrove (diesel service from Skegness, Grantham, Nottingham Derby and Stoke-on-Trent) |

| + | Junction | 14 | The Welsh Marches Line from South Wales, Hereford and Shrewsbury |

| + | Junction | 22 | to Chester and the North Wales Coast Line |

| + | Junction | 20 | to Wilmslow, Manchester Airport, Stockport and Manchester |

| Hartford North | Junction | 20 | (freight only) from Northwich |

| Weaver Jnct | Branch | 18 | to Runcorn and Liverpool (Route 20 from Liverpool South Parkway railway station) |

| Liverpool South Parkway | – | 20 | Route 18 London to Liverpool Line becomes Route 20 to Liverpool Lime Street |

| Warrington | Junction | 22 | from Llandudno and Chester to Manchester |

| Winwick Jnct | Junction | 20 | to Liverpool, Earlestown and Manchester |

| Golborne Jnct | Junction | 20 | to Liverpool, Newton-le-Willows and Manchester |

| Ince Moss/Springs Branch Junct | Junction | 20 | The Liverpool to Wigan Line |

| Wigan | Junction | 20 | from Manchester |

| Euxton Jnct | Junction | 20 | The Manchester to Preston Line from Manchester |

| Farington Jnct | Junction | 23 | East Lancashire Line and Caldervale Line |

| Farington Curve Jnct | Junction | 23 | Ormskirk Branch Line, East Lancashire Line and Caldervale Line |

| Preston Dock | Junction | 23 | west |

| Preston | Junction | 20 | to Blackpool |

| Morecambe South Jnct | Junction | 23 | to Morecambe |

| Hest Bank Jnct | Junction | 23 | from Morecambe |

| Carnforth Jnct | Junction | 23 | Furness Line to Barrow-in-Furness and also the Leeds to Morecambe Line to Leeds |

| Oxenholme | Junction | 23 | to Windermere |

| Penrith | Junction | 23 | Route 23 uses two junctions to the north of the station |

| Carlisle | Junction | 23 | Route 23 Settle-Carlisle Railway and Route 9 from Newcastle |

| + | Junction | 23 | The Cumbrian Coast Line from Barrow-in-Furness |

| Gretna Jnct | Junction | 26 | to the Glasgow South Western Line |

| Carstairs South Jnct | Junction | 24 | Route 18 West Coast Main Line becomes Route 24 to Edinburgh |

| Carstairs South | – | 26 | Route 18 West Coast Main Line becomes Route 26 to Glasgow |

See also

- East Coast Main Line

- Portpatrick Railway

- Castle Douglas and Dumfries Railway

- Irish Sea tunnel

- Rail transport in Great Britain

References

- 1 2 "West Coast Main Line Pendolino Tilting Trains, United Kingdom". railway-technology.com. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- 1 2 "High-speed tilting train on track", BBC News Online, 12 December 2005.

- 1 2 3 Network Rail media centre, December 2008.

- ↑ West Coast Main Line, Network Rail, October 2007.

- ↑ "General definitions of highspeed". International Union of Railways. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 British Railways Board (1974).Electric All The Way. Information booklet.

- ↑ History of the West Coast Main Line, Virgin Trains, July 2004.

- ↑ Grand Junction Railway: History of the West Coast Main line, Virgin Trains 2004.

- 1 2 London and Birmingham Railway: History of the West Coast Main line, Virgin Trains 2004.

- ↑ Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-85260-049-7. OCLC 19514063.

- ↑ The Manchester Lines: History of the West Coast Main line. Virgin Trains (2004).

- ↑ "Carriages of LNWR Photographs". lnwrs.org.uk.

- ↑ Thomas, John (1971). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. Volume VI Scotland: The Lowlands and the Borders (1st ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. OCLC 650446341.

- ↑ Lines in Lancashire: History of the West Coast Main line. Virgin Trains (2004).

- ↑ "Rail Album – LMS Steam Locos – Streamlined Princess Coronation Class Pacifics – Part 1". railalbum.co.uk.

- ↑ "The winter timetables of British Railways: The West Coast speed-up". Trains Illustrated (Hampton Court: Ian Allan). December 1959. p. 584.

- ↑ "Auction Announcements of Messrs. Knight, Frank, and Rutley". The Times (London). 27 April 1912. p. 22.

"The Abington and Crawford Estates ... extending as they do for some 12 miles either side of the main road and the West Coast Main Line to the North, with Abington and Crawford Stations on the Estate.

- ↑ Marshall, John (1979). The Guinness Book Of Rail Facts & Feats. Enfield: Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 0-900424-56-7.

- ↑ Wolmar, Christian (2007). Fire and Steam, A New History of the Railways in Britain. London: Atlantic. ISBN 978-1-84354-629-0.

- ↑ Passenger Timetable 1 May 1972 to 6 May 1973. British Railways Board, London Midland Region. pp. 83, 06.

- ↑ British Railways Board (April 1966).Your New Railway: London Midland Electrification. Information booklet.

- ↑ Potter, Stephen; Roy, Robin (1986). Research and development: British Rail's fast trains. Design and Innovation, Block 3. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-335-17273-3.

- ↑ Stamp, Gavin (1 October 2007). "Steam ahead: the proposed rebuilding of London's Euston station is an opportunity to atone for a great architectural crime". Apollo: the international magazine of art and antiques. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- ↑ Semmens, Peter (1991). Electrifying the East Coast Route. ISBN 0-85059-929-6.

- ↑ 'Queasy Rider:' The Failure of the Advanced Passenger Train.

- ↑ Meek, James (1 April 2004). "The £10bn Rail Crash". The Guardian (London).

- ↑ "West Coast rail works completed". BBC News Online. 14 December 2008.

- ↑ "West coast main line upgrade". Corus rail. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ↑ "Freight Route Utilisation Strategy – March 2007" (PDF). Network Rail. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ↑ "Railroad/Railway Electric Traction Systems". crbasic.info. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ "North West electrification". Network Rail. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ "Virgin Rail Group welcomes West Coast franchise extension discussions". Rail Network. 21 May 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ↑ West Coast Main Line – Written statements to Parliament. GOV.UK (15 October 2012). Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ↑ "WCML 2008 timetable Virgin Trains" (PDF). Virgin Trains.

- ↑ Distances are based on http://www.networkrail.co.uk/aspx/3828.aspx (Tables 65, 75, 81), as of 9 October 2015.

- ↑ "Train Times" (PDF). East Coast. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ "Nuneaton North Chord freight line now open". Network Rail. 15 November 2012.

- ↑ "Work starts on Nuneaton chord". Rail (Peterborough). 10 August 2011. p. 20.

- ↑ "The new Ipswich chord will ease a major bottleneck on the Great Eastern main line". Network Rail. 25 March 2014.

- ↑ "Stafford – Crewe rail enhancements". Network Rail. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- 1 2 "8. Potential new lines". London and South East Route Utilisation Strategy. Network Rail. 28 July 2011. pp. 149–153.

- 1 2 Business plan 2007, Network Rail.

- ↑ Hansard (House of Commons), 4 November 2009.

- ↑ Connor, Neil (25 April 2006). "We won't bid if rail link becomes a 'bus run'". icBirmingham.co.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ "Government launches study into potential Crossrail extension".

- ↑ "Ministry of Transport Accident Report Between Grayrigg and Oxenholme, L.M.S.R., 18 May 1947". Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ↑ Route plans, Network Rail.

- ↑ Network Rail Route 18.

Sources

- Buck, Martin; Rawlinson, Mark (2000). Line By Line: The West Coast Main Line, London Euston to Glasgow Central. Swindon: Freightmaster Publishing. ISBN 0-9537540-0-6.

- "EUSTON MAIN LINE ELECTRIFICATION, A Technical Conference sponsored jointly by the British Railways Board and the Institutions of Civil, Mechanical, Electrical, Locomotive, and Railway Signal Engineers, 25–26th October 1966". Conference Proceedings (Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMECH)) 181 (6 (Part 3F)). 1966–67.

- Brentnall, E. G. (1966). "Signalling and telecommunications works on the Euston main line electrification". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Conference Proceedings 1964–1970 (vols 178-184) 181 (36): 65–86. doi:10.1243/PIME_CONF_1966_181_108_02.

- Butland, A. N. (1966). "Civil engineering works of the Euston main line electrification scheme". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Conference Proceedings 1964–1970 (vols 178-184) 181 (36): 51–64. doi:10.1243/PIME_CONF_1966_181_107_02.

- Emerson, A. H. (1966). "Electrification of the London Midland main line from Euston". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Conference Proceedings 1964–1970 (vols 178-184) 181 (36): 17–50. doi:10.1243/PIME_CONF_1966_181_105_02.

Further reading

- Ballantyne, Hugh (1989). The Colour of British Rail: West Coast Main Line 2. Atlantic Transport Publishers. ISBN 9780906899328. OCLC 21600017.

- Beecroft, Don; Pirt, Keith (2008). Steam memories: 1950's - 1960's. No. 21, West coast main line & branches in Lancashire : including Wigan, Preston, Lancaster, Morecambe, Carnforth and Blackpool. Challenger Publications. ISBN 9781899624997. OCLC 528374617.

- Joy, David (1967). Main Line Over Shap. Dalesman Publishing Co. Ltd. ISBN 9780852060636. OCLC 12273695.

- Longhurst, Roly (1979). Electric Locomotives of the West Coast Main Line. Bardford Barton. ISBN 9780851533551. OCLC 16491712.

- McCutcheon, Campbell; Christopher, John (2014). Bradshaw's Guide: West Coast Main Line, Manchester to Glasgow 10. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445640419. OCLC 902726172.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Coast Main Line. |

- Electric All The Way – 1974 British Rail information booklet about the completion of electrification to Glasgow.

- Rail Industry www page which monitors the progress of the project

- Department of Transport – 2006 – West Coast Main Line – Update Report

- Network Rail Business Plans and Reports

- British Railways in 1960, Euston to Crewe

- British Railways in 1960, Crewe to Carlisle

- British Railways in 1960, Carlisle to Carstairs

- British Railways in 1960, Carstairs to Glasgow

- London to Glasgow in five minutes – BBC video, December 2008

- Origins of 1849 stretch of line from Glasgow to Carlisle

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 52°10′41″N 0°55′27″W / 52.17801°N 0.92405°W