Wave function

A wave function in quantum mechanics is a mathematical object that represents a particular quantum state of a specific isolated system of one or more particles. A single wave function describes the entire system, covering at once all the particles in it. For the one state, however, there are many different wave functions, each giving its respective representative description. Each of the different representatives contains all the information that can be known about the state, the different versions being mutually interconvertible by one-to-one mathematical transformations. A wave function can be interpreted as a probability amplitude. All quantities associated with measurements, such as the average momentum of a particle, can be derived from the wave function. It is a central entity in quantum mechanics, including for example quantum field theory. The most common symbols for a wave function are the Greek letters ψ or Ψ (lower-case and capital psi).

For a specific system, there are many possible representations, that is to say, complete sets of commuting observables, and many suitable coordinate systems, continuous as well as discrete. These may be freely chosen. For the particular state, there is one representative wave function, a complex-valued function of the system's degrees of freedom, that belongs to the chosen representation and coordinate system. By a postulate of quantum mechanics, such observables are Hermitian linear operators on the space of states, representing physical observables, for example position, momentum and spin, that can, in principle, be simultaneously or jointly measured with arbitrary precision. There is at least one such complete set of observables for which the state is a simultaneous eigenstate.

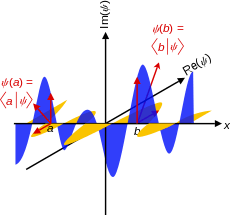

Wave functions can be added together and multiplied by complex numbers to form new wave functions, and hence are elements of a vector space. This is the superposition principle of quantum mechanics. This vector space is endowed with an inner product such that it is a complete metric topological space with respect to the metric induced by the inner product. In this way the set of wave functions for a system form a function space that is a Hilbert space. The inner product is a measure of the overlap between physical states and is used in the foundational probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics, the Born rule, relating transition probabilities to inner products. The actual space depends on the system's degrees of freedom (hence on the chosen representation and coordinate system) and the exact form of the Hamiltonian entering the equation governing the dynamical behavior. In the non-relativistic case, disregarding spin, this is the Schrödinger equation.

The Schrödinger equation determines the allowed wave functions for the system and how they evolve over time. Because that equation is mathematically a type of wave equation, a wave function behaves in some respects like other waves, such as water waves or waves on a string. This explains the name "wave function", and gives rise to wave–particle duality. The wave of the wave function, however, is not a wave in ordinary physical space; it is a wave in an abstract mathematical "space", and in this respect it differs fundamentally from water waves or waves on a string.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

For a given system, the choice of which relevant degrees of freedom to use are not unique, and correspondingly the domain of the wave function is not unique. It may be taken to be a function of all the position coordinates of the particles over position space, or the momenta of all the particles over momentum space, the two are related by a Fourier transform. These descriptions are the most important, but they are not the only possibilities. Just like in classical mechanics, canonical transformations may be used in the description of a quantum system. Some particles, like electrons and photons, have nonzero spin, and the wave function must include this fundamental property as an intrinsic discrete degree of freedom. In general, for a particle with half-integer spin the wave function is a spinor, for a particle with integer spin the wave function is a tensor. Particles with spin zero are called scalar particles, those with spin 1 vector particles, and more generally for higher integer spin, tensor particles. The terminology derives from how the wave functions transform under a rotation of the coordinate system. No elementary particle with spin 3⁄2 or higher is known, except for the hypothesized spin 2 graviton. Other discrete variables can be included, such as isospin. When a system has internal degrees of freedom, the wave function at each point in the continuous degrees of freedom (e.g. a point in space) assigns a complex number for each possible value of the discrete degrees of freedom (e.g. z-component of spin). These values are often displayed in a column matrix (e.g. a 2 × 1 column vector for a non-relativistic electron with spin 1⁄2).

In Born's statistical interpretation,[8][9][10] the squared modulus of the wave function, |ψ|2, is a real number interpreted as the probability density of measuring a particle's being detected at a given place, or having a given momentum, at a given time, and possibly having definite values for discrete degrees of freedom. The integral of this quantity, over all the system's degrees of freedom, must be 1 in accordance with the probability interpretation, this general requirement a wave function must satisfy is called the normalization condition. Since the wave function is complex valued, only its relative phase and relative magnitude can be measured. Its value does not in isolation tell anything about the magnitudes or directions of measurable observables; one has to apply quantum operators, whose eigenvalues correspond to sets of possible results of measurements, to the wave function ψ and calculate the statistical distributions for measurable quantities.

The unit of measurement for ψ depends on the system, and can be found by dimensional analysis of the normalization condition for the system. For one particle in three dimensions, its units are [length]−3/2, because an integral of |ψ|2 over a region of three-dimensional space is a dimensionless probability.[11]

Historical background

In 1905 Einstein postulated the proportionality between the frequency of a photon and its energy, E = hf,[12] and in 1916 the corresponding relation between photon momentum and wavelength, λ = h/p.[13] In 1923, De Broglie was the first to suggest that the relation λ = h/p, now called the De Broglie relation, holds for massive particles, the chief clue being Lorentz invariance,[14] and this can be viewed as the starting point for the modern development of quantum mechanics. The equations represent wave–particle duality for both massless and massive particles.

In the 1920s and 1930s, quantum mechanics was developed using calculus and linear algebra. Those who used the techniques of calculus included Louis de Broglie, Erwin Schrödinger, and others, developing "wave mechanics". Those who applied the methods of linear algebra included Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, and others, developing "matrix mechanics". Schrödinger subsequently showed that the two approaches were equivalent.[15]

In 1926, Schrödinger published the famous wave equation now named after him, indeed the Schrödinger equation, based on classical Conservation of energy using quantum operators and the de Broglie relations such that the solutions of the equation are the wave functions for the quantum system.[16] However, no one was clear on how to interpret it.[17] At first, Schrödinger and others thought that wave functions represent particles that are spread out with most of the particle being where the wave function is large.[18] This was shown to be incompatible with how elastic scattering of a wave packet representing a particle off a target appears; it spreads out in all directions.[8] While a scattered particle may scatter in any direction, it does not break up and take off in all directions. In 1926, Born provided the perspective of probability amplitude.[8][9][19] This relates calculations of quantum mechanics directly to probabilistic experimental observations. It is accepted as part of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. There are many other interpretations of quantum mechanics. In 1927, Hartree and Fock made the first step in an attempt to solve the N-body wave function, and developed the self-consistency cycle: an iterative algorithm to approximate the solution. Now it is also known as the Hartree–Fock method.[20] The Slater determinant and permanent (of a matrix) was part of the method, provided by John C. Slater.

Schrödinger did encounter an equation for the wave function that satisfied relativistic energy conservation before he published the non-relativistic one, but discarded it as it predicted negative probabilities and negative energies. In 1927, Klein, Gordon and Fock also found it, but incorporated the electromagnetic interaction and proved that it was Lorentz invariant. De Broglie also arrived at the same equation in 1928. This relativistic wave equation is now most commonly known as the Klein–Gordon equation.[21]

In 1927, Pauli phenomenologically found a non-relativistic equation to describe spin-1/2 particles in electromagnetic fields, now called the Pauli equation.[22] Pauli found the wave function was not described by a single complex function of space and time, but needed two complex numbers, which respectively correspond to the spin +1/2 and −1/2 states of the fermion. Soon after in 1928, Dirac found an equation from the first successful unification of special relativity and quantum mechanics applied to the electron, now called the Dirac equation. In this, the wave function is a spinor represented by four complex-valued components:[20] two for the electron and two for the electron's antiparticle, the positron. In the non-relativistic limit, the Dirac wave function resembles the Pauli wave function for the electron. Later, other relativistic wave equations were found.

Wave functions and wave equations in modern theories

All these wave equations are of enduring importance. The Schrödinger equation and the Pauli equation are under many circumstances excellent approximations of the relativistic variants. They are considerably easier to solve in practical problems than the relativistic equations. The Klein-Gordon equation and the Dirac equation, while being relativistic, do not represent full reconciliation of quantum mechanics and special relativity. The branch of quantum mechanics where these equations are studied the same way as the Schrödinger equation, often called relativistic quantum mechanics, while very successful, has its limitations (see e.g. Lamb shift) and conceptual problems (see e.g. Dirac sea).

Relativity makes it inevitable that the number of particles in a system is not constant. For full reconciliation, quantum field theory is needed.[23] In this theory, the wave equations and the wave functions have their place, but in a somewhat different guise. The main objects of interest are not the wave functions, but rather operators, so called field operators (or just fields where "operator" is understood) on the Hilbert space of states (to be described next section). It turns out that the original relativistic wave equations and their solutions are still needed to build the Hilbert space. Moreover, the free fields operators, i.e. when interactions are assumed not to exist, turn out to (formally) satisfy the same equation as do the fields (wave functions) in many cases.

Thus the Klein-Gordon equation (spin 0) and the Dirac equation (spin 1⁄2) in this guise remain in the theory. Higher spin analogues include the Proca equation (spin 1), Rarita–Schwinger equation (spin 3⁄2), and, more generally, the Bargmann–Wigner equations. For massless free fields two examples are the free field Maxwell equation (spin 1) and the free field Einstein equation (spin 2) for the field operators.[24] All of them are essentially a direct consequence of the requirement of Lorentz invariance. Their solutions must transform under Lorentz transformation in a prescribed way, i.e. under a particular representation of the Lorentz group and that together with few other reasonable demands, e.g. the cluster decomposition principle,[25] with implications for causality is enough to fix the equations.

It should be emphasized that this applies to free field equations; interactions are not included. It should also be noted that the equations and their solutions, though needed for the theories, are not the central objects of study.

Wave functions and function spaces

The concept of Function spaces enters naturally in the discussion about wave functions. A function space is a set of functions, usually with some defining requirements on the functions, together with a topology on that set. The latter will sparsely be used here, it is only needed to obtain a precise definition of what it means for a subset of a function space to be closed. A wave function is an element of a function space partly characterized by the following concrete and abstract descriptions.

- The Schrödinger equation is linear. This means that the solutions to it, wave functions, can be added and multiplied by scalars to form a new solution.

- The superposition principle of quantum mechanics. If Ψ and Φ are two states in the abstract space of states of a quantum mechanical system, then aΨ + bΦ is a valid state as well.

The first item says that the set of solutions to the Schrödinger equation is a vector space. The second item says that the set of allowable states is a vector space. This similarity is of course not accidental. Not all properties of the respective spaces have been given so far. There are also a distinctions between the spaces to keep in mind.

- Basic states are characterized by a set of quantum numbers. This is a set of eigenvalues of a complete set of commuting observables. A choice of such a set may be called a choice of representation. It is a postulate of quantum mechanics that a physically observable quantity of a system, such as position, momentum, or spin, is represented by a linear Hermitian operator on the state space. The possible outcomes of measurement of the quantity are the eigenvalues of the operator.[18] Completeness means that there can be added to the set no further algebraically independent linear Hermitian operator that commutes with the ones already present. The physical interpretation is that such a set represents what can – in theory – be simultaneously be measured with arbitrary precision. The set is non-unique. It may for a one-particle system, for example, be position and spin z-projection, (x, Sz), or it may be momentum and spin y-projection, (p, Sy). At a deeper level, most observables, perhaps all, arise as generators of symmetries.[18][26][nb 1]

- Once a representation is chosen, there is still arbitrariness. It remains to choose a coordinate system. This may, for example, correspond to a choice of x, y- and z-axis, or a choice of curvlinear coordinates as exemplified by the spherical coordinates used for the atomic wave functions illustrated below. This final choice also fixes a basis in abstract Hilbert space. The basic states are labeled by the quantum numbers corresponding to the complete set of commuting observables and an appropriate coordinate system.[nb 2]

- Wave functions corresponding to a state are accordingly not unique. This has been exemplified already with momentum and position space wave functions describing the same abstract state. This non-uniqueness reflects the non-uniqueness in the choice of a complete set of commuting observables.

- The abstract states are "abstract" only in that an arbitrary choice necessary for a particular explicit description of it is not given. This is the same as saying that no choice of complete set of commuting observables has been given. This is analogous to a vector space without a specified basis.

- The wave functions of position and momenta, respectively, can be seen as a choice of representation yielding two different, but entirely equivalent, explicit descriptions of the same state for a system with no discrete degrees of freedom.

- Corresponding to the two examples in the first item, to a particular state there corresponds two wave functions, Ψ(x, Sz) and Ψ(p, Sy), both describing the same state. For each choice of complete commuting sets of observables for the abstract state space, there is a corresponding representation that is associated to a function space of wave functions.

- Each choice of representation should be thought of as specifying a unique function space in which wave functions corresponding to that choice of representation lives. This distinction is best kept, even if one could argue that two such function spaces are mathematically equal, e.g. being the set of square integrable functions. One can then think of the function spaces as two distinct copies of that set.

- Between all these different function spaces and the abstract state space, there are one-to-one correspondences (here disregarding normalization and unobservable phase factors), the common denominator here being a particular abstract state. The relationship between the momentum and position space wave functions, for instance, describing the same state is the Fourier transform.

To make this concrete, in the figure to the right, the 19 sub-images are images of wave functions in position space (their norm squared). The wave functions each represent the abstract state characterized by the triple of quantum numbers (n, l, m), in the lower right of each image. These are the principal quantum number, the orbital angular momentum quantum number and the magnetic quantum number. Together with one spin-projection quantum number of the electron, this is a complete set of observables.

The figure can serve to illustrate some further properties of the function spaces of wave functions.

- In this case, the wave functions are square integrable. One can initially take the function space as the space of square integrable functions, usually denoted L2.

- The displayed functions are solutions to the Schrödinger equation. Obviously, not every function in L2 satisfies the Schrödinger equation for the hydrogen atom. The function space is thus a subspace of L2.

- The displayed functions form part of a basis for the function space. To each triple (n, l, m), there corresponds a basis wave function. If spin is taken into account, there are two basis functions for each triple. The function space thus has a countable basis.

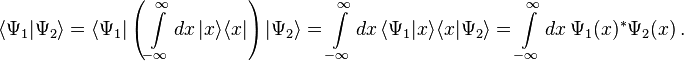

- The basis functions are mutually orthonormal. For this concept to have a meaning, there must exist an inner product. The function space is thus an inner product space. The inner product between two states intuitively measures the "overlap" between the states. The physical interpretation is that the norm squared is proportional to the transition probability between the states. That is.

,

,

- where the i is an index composed of quantum numbers corresponding to a representation and the probabilities are the probabilities of finding the state Ψ in the definite state represented by Φi upon measurement of the physical observables corresponding to the representation, for instance, i could be the quadruple (n, l, m, Sz). This is the Born rule,[8] and is one of the fundamental postulates of quantum mechanics.

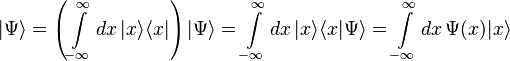

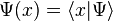

These observations encapsulate the essence of the function spaces of which wave functions are elements. Mathematically, this is expressed (in one spatial dimension, disregarding here unimportant issues of normalization) for a particle with no internal degrees of freedom as

where Ψ is any "abstract" state, Φx is an eigenfunction of the position operator representing a particle localized at x, (·,·) represents the inner product, Φp is an eigenfunction of the momentum operator representing a particle with precise momentum p, I is the identity operator and the integrals (first and third) represent the completeness of momentum and position eigenstates, Ψ(x) is the coordinate space wave function and Ψ(p) is the wave function in momentum space. In Dirac notation, the above equation reads

The description is not yet complete. There is a further technical requirement on the function space, that of completeness, that allows one to take limits of sequences in the function space, and be ensured that, if the limit exists, it is an element of the function space. A complete inner product space is called a Hilbert space. The property of completeness is crucial in advanced treatments and applications of quantum mechanics. It will not be very important in the subsequent discussion of wave functions, and technical details and links may be found in footnotes like the one that follows.[nb 3] The space L2 is a Hilbert space, with inner product presented later. The function space of the example of the figure is a subspace of L2. A subspace of a Hilbert space is a Hilbert space if it is closed. It is here that the topology of the function space enters into its description.

It is also important to note, in order to avoid confusion, that not all functions to be discussed are elements of some Hilbert space, say L2. The most glaring example is the set of functions e2πipx⁄h. These are solutions of the Schrödinger equation for a free particle, but are not normalizable, hence not in L2. But they are nonetheless fundamental for the description. One can, using them, express functions that are normalizable using wave packets. They are, in a sense to be made precise later, a basis (but not a Hilbert space basis) in which wave functions of interest can be expressed. There is also the artifact "normalization to a delta function" that is frequently employed for notational convenience, see further down. The delta functions themselves aren't square integrable either.

Physical requirements

The above description of the function space containing the wave functions is mostly mathematically motivated. The function spaces are, due to completeness, very large in a certain sense. Not all functions are realistic descriptions of any physical system. For instance, in the function space L2 one can find the function that takes on the value 0 for all rational numbers and -i for the irrationals in the interval [0, 1]. This is square integrable,[nb 4] but can hardly represent a physical state.

The following constraints on the wave function are sometimes explicitly formulated for the calculations and physical interpretation to make sense:[27][28]

- The wave function must be square integrable. This is motivated by the Copenhagen interpretation of the wave function as a probability amplitude.

- It must everywhere be everywhere continuous and everywhere continuously differentiable. This is motivated by the appearance of the Schrödinger equation.

It is possible to relax these conditions somewhat for special purposes.[nb 5] If these requirements are not met, it is not possible to interpret the wave function as a probability amplitude.[29]

This does not alter the structure of the Hilbert space that these particular wave functions inhabit, but it should be pointed out that the subspace of the square-integrable functions L2, which is a Hilbert space, satisfying the second requirement is not closed in L2, hence not a Hilbert space in itself.[nb 6] The functions that does not meet the requirements are still needed for both technical and practical reasons.[nb 7][nb 8]

Definition (one spinless particle in 1d)

For now, consider the simple case of a single particle, without spin, in one spatial dimension. More general cases are discussed below.

Position-space wave function

The state of such a particle is completely described by its wave function,

where x is position and t is time. This is a complex-valued function of two real variables x and t.

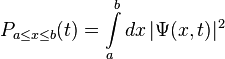

If interpreted as a probability amplitude, the square modulus of the wave function, the positive real number

is interpreted as the probability density that the particle is at x. The asterisk indicates the complex conjugate. If the particle's position is measured, its location cannot be determined from the wave function, but is described by a probability distribution. The probability that its position x will be in the interval a ≤ x ≤ b is the integral of the density over this interval:

where t is the time at which the particle was measured. This leads to the normalization condition:

because if the particle is measured, there is 100% probability that it will be somewhere.

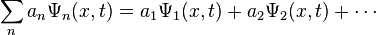

Since the Schrödinger equation is linear, if any number of wave functions Ψn for n = 1, 2, ... are solutions of the equation, then so is their sum, and their scalar multiples by complex numbers an. Taking scalar multiplication and addition together is known as a linear combination:

This is the superposition principle. Multiplying a wave function Ψ by any nonzero constant complex number c to obtain cΨ does not change any information about the quantum system, because c cancels in the Schrödinger equation for cΨ.

Momentum-space wave function

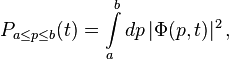

The particle also has a wave function in momentum space:

where p is the momentum in one dimension, which can be any value from −∞ to +∞, and t is time.

All the previous remarks on superposition, normalization, etc. apply similarly. In particular, if the particle's momentum is measured, the result is not deterministic, but is described by a probability distribution:

and the normalization condition is:

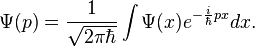

Relation between wave functions

From the introduction to the section Wave functions and function spaces above, considering the one-dimensional non-relativistic case for a single particle,

Now take the projection of the state Ψ onto eigenfunctions of momentum using the last expression in the two equations,[30]

Then utilizing the known expression for suitably normalized eigenstates of momentum in the position representation solutions of the free Schrödinger equation

one obtains

Likewise, using eigenfunctions of position,

The position-space and momentum-space wave functions are thus found to be Fourier transforms of each other. The two wave functions contain the same information, and either one alone is sufficient to calculate any property of the particle. As representatives of elements of abstract physical Hilbert space, whose elements are the possible states of the system under consideration, they represent the same state vector, hence identical physical states, but they are not generally equal when viewed as square-integrable functions. For one dimension,[31]

In practice, the position-space wave function is used much more often than the momentum-space wave function. The potential entering the relevant equation (Schrödinger, Dirac, etc) determines in which basis the description is easiest. For the harmonic oscillator, x and p enter symmetrically, so there it doesn't matter which description one uses. The same equation (modulo constants) results. From this follows, with a little bit of afterthought, a factoid: The solutions to the wave equation of the harmonic oscillator are eigenfunctions of the Fourier transform in L2![nb 9]

Definitions (other cases)

Following are the general forms of the wave function for systems in higher dimensions and more particles, as well as including other degrees of freedom than position coordinates or momentum components.

The position-space wave function of a single particle in three spatial dimensions is similar to the case of one spatial dimension above:

where r is the position vector in three-dimensional space, and t is time. As always Ψ(r, t) is a complex number, for this case a complex-valued function of four real variables.

If there are many particles, in general there is only one wave function, not a separate wave function for each particle. The fact that one wave function describes many particles is what makes quantum entanglement and the EPR paradox possible. The position-space wave function for N particles is written:[20]

where ri is the position of the ith particle in three-dimensional space, and t is time. Altogether, this is a complex-valued function of 3N + 1 real variables.

In quantum mechanics there is a fundamental distinction between identical particles and distinguishable particles. For example, any two electrons are identical and fundamentally indistinguishable from each other; the laws of physics make it impossible to "stamp an identification number" on a certain electron to keep track of it.[31] This translates to a requirement on the wave function for a system of identical particles:

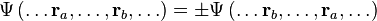

where the + sign occurs if the particles are all bosons and − sign if they are all fermions. In other words, the wave function is either totally symmetric in the positions of bosons, or totally antisymmetric in the positions of fermions.[32] The physical interchange of particles corresponds to mathematically switching arguments in the wave function. The antisymmetry feature of fermionic wave functions leads to the Pauli principle. Generally, bosonic and fermionic symmetry requirements are the manifestation of particle statistics and are present in other quantum state formalisms.

For N distinguishable particles (no two being identical, i.e. no two having the same set of quantum numbers), there is no requirement for the wave function to be either symmetric or antisymmetric.

For a collection of particles, some identical with coordinates r1, r2, ... and others distinguishable x1, x2, ... (not identical with each other, and not identical to the aforementioned identical particles), the wave function is symmetric or antisymmetric in the identical particle coordinates ri only:

Again, there is no symmetry requirement for the distinguishable particle coordinates xi.

For a particle with spin, the wave function can be written in "position–spin space" as:

which is a complex-valued function of position r in three-dimensional space, time t, and sz, the spin projection quantum number along the z axis. (The z axis is an arbitrary choice; other axes can be used instead if the wave function is transformed appropriately, see below.) The sz parameter, unlike r and t, is a discrete variable. For example, for a spin-1/2 particle, sz can only be +1/2 or −1/2, and not any other value. (In general, for spin s, sz can be s, s − 1, ... , −s + 1, −s.)

Often, the complex values of the wave function for all the spin numbers are arranged into a column vector, in which there are as many entries in the column vector as there are allowed values of sz. In this case, the spin dependence is placed in indexing the entries and the wave function is a complex vector-valued function of space and time only:

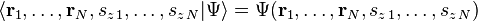

The wave function for N particles each with spin is the complex-valued function:

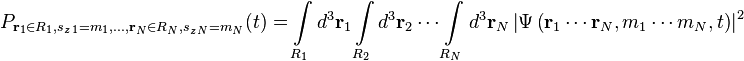

Concerning the general case of N particles with spin in 3d, if Ψ is interpreted as a probability amplitude, the probability density is:

and the probability that particle 1 is in region R1 with spin sz1 = m1 and particle 2 is in region R2 with spin sz2 = m2 etc. at time t is the integral of the probability density over these regions and spins:

The multidimensional Fourier transforms of the position or position–spin space wave functions yields momentum or momentum–spin space wave functions.

Decompositions into products

For systems in time-independent potentials, the wave function can always be written as a function of the degrees of freedom multiplied by a time-dependent phase factor, the form of which is given by the Schrödinger equation. For the case of N particles position-spin space,

where E is the energy eigenvalue of the system corresponding to the eigenstate Ψ. Wave functions of this form are called stationary states.

In some situations, the wave function for a particle with spin factors into a product of a space function ψ and a spin function ξ, where each are complex-valued functions, and the time dependence can be placed in either function:

The dynamics of each factor can be studied in isolation. This factorization is always possible when the orbital and spin angular momenta of the particle are separable in the Hamiltonian operator, that is, the Hamiltonian can be split into an orbital term and a spin term.[33] It is not possible for those interactions where an external field or any space-dependent quantity couples to the spin; examples include a particle in a magnetic field, and spin-orbit coupling. For the time-independent case this reduces to

where again E is the energy eigenvalue of the system corresponding to the eigenstate Ψ. This extends to the case of N particles:

and for the case of identical particles, each factor has to have the correct antisymmetry or symmetry, to make the overall wave function antisymmetric for fermions or symmetric for bosons.

Inner product

Position-space inner products

The inner product of two wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2 is useful and important for a number of reasons given below. For the case of one spinless particle in 1d, it can be defined as the complex number (at time t)[nb 10]

More generally, the formulae for the inner products are integrals over all coordinates or momenta and sums over all spin quantum numbers. That is, for one spinless particle in 3d the inner product of two wave functions can be defined as the complex number:

while for many spinless particles in 3d:

(altogether, this is N three-dimensional volume integrals with differential volume elements d3ri, also written "dVi" or "dxi dyi dzi"). For one particle with spin in 3d:

and for the general case of N particles with spin in 3d:

(altogether, N three-dimensional volume integrals followed by N sums over the spins).

In the Copenhagen interpretation, the modulus squared of the inner product (a complex number) gives a real number

which is interpreted as the probability of the wave function Ψ2 "collapsing" to the new wave function Ψ1 upon measurement of an observable, whose eigenvalues are the possible results of the measurement, with Ψ1 being an eigenvector of the resulting eigenvalue.

Although the inner product of two wave functions is a complex number, the inner product of a wave function Ψ with itself,

is always a positive real number. The number ||Ψ|| (not ||Ψ||2) is called the norm of the wave function Ψ, and is not the same as the modulus |Ψ|.

A wave function is normalized if:

If Ψ is not normalized, then dividing by its norm gives the normalized function Ψ/||Ψ||.

Two wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2 are orthogonal if their inner product is zero:

A set of wave functions Ψ1, Ψ2, ... are orthonormal if they are each normalized and are all orthogonal to each other:

where m and n each take values 1, 2, ..., and δmn is the Kronecker delta (+1 for m = n and 0 for m ≠ n). Orthonormality of wave functions is instructive to consider since this guarantees linear independence of the functions. (However, the wave functions do not have to be orthonormal and can still be linearly independent, but the inner product of Ψm and Ψn is more complicated than the mere δmn).

Returning to the superposition above:

if the basis wave functions ψn are orthonormal, then the coefficients have a particularly simple form:

If the basis wave functions were not orthonormal, then the coefficients would be different.

Momentum-space inner products

Analogous to the position case, the inner product of two wave functions Φ1(p, t) and Φ2(p, t) can be defined as:

and similarly for more particles in higher dimensions.

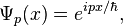

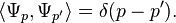

One particular solution to the time-independent Schrödinger equation is

a plane wave, which can be used in the description of a particle with momentum exactly p, since it is an eigenfunction of the momentum operator. These functions are not normalizable to unity (they aren't square-integrable), so they are not really elements of physical Hilbert space. The set

forms what is called the momentum basis. This "basis" is not a basis in the usual mathematical sense. For one thing, since the functions aren't normalizable, they are instead normalized to a delta function,

For another thing, though they are linearly independent, there are too many of them (they form an uncountable set) for a basis for physical Hilbert space. They can still be used to express all functions in it using Fourier transforms as described above.

Units of the wave function

Although wave functions are complex numbers, both the real and imaginary parts each have the same units (the imaginary unit i is a pure number without physical units). The units of ψ depend on the number of particles N the wave function describes, and the number of spatial or momentum dimensions n of the system.

When integrating |ψ|2 over all the coordinates, the volume element dnr1dnr2...dnrN has units of [length]Nn. Since the normalization conditions require the integral to be the unitless number 1, |ψ|2 must have units of [length]−Nn, thus the units of |ψ| and hence ψ are [length]−Nn/2. Likewise, in momentum space, length is replaced by momentum, and the units are [momentum]−Nn/2. These results are true for particles of any spin, since for particles with spin, the summations are over dimensionless spin quantum numbers.

More on wave functions and abstract state space

As has been demonstrated, the set of all possible normalizable wave functions for a system with a particular choice of basis constitute a Hilbert space. This vector space is in general infinite-dimensional. Due to the multiple possible choices of basis, these Hilbert spaces are not unique. One therefore talks about an abstract Hilbert space, state space, where the choice of basis is left undetermined. The choice of basis corresponds to a choice of a complete set of quantum numbers, each quantum number corresponding to an observable. Two observables corresponding to quantum numbers in the complete set must commute, therefore, the basis isn't entirely arbitrary, but nonetheless, there are always several choices.

Specifically, each state is represented as an abstract vector in state space[34]

where |Ψ⟩ is a "ket" (a vector) written in Dirac's bra–ket notation.[35] Kets that differ by multiplication by a scalar represent the same state. A ray in Hilbert space is a set of normalized vectors differing by a complex number of modulus 1. If |ψ⟩ and |ϕ⟩ are two states in the vector space, and a and b are two complex numbers, then the linear combination

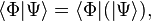

is also in the same vector space. The state space is postulated to have an inner product, denoted by

that is (usually, this differs) linear in the first argument and antilinear in the second argument. The dual vectors are denoted as "bras", ⟨Ψ|. These are linear functionals, elements of the dual space to the state space. The inner product, once chosen, can be used to define a unique map from state space to its dual, see Riesz representation theorem. this map is antilinear. One has

where the asterisk denotes the complex conjugate. For this reason one has under this map

and one may, as a practical consequence, at least notation-wise in this formalism, ignore that bra's are dual vectors.

The state vector for the system evolves in time according to the Schrödinger equation, or other dynamical pictures of quantum mechanics- In bra-ket notation this reads,

Abstract state space is also, by definition, required to be a Hilbert space. The only requirement missing for this in the description so far is completeness. See the quantum state article for more explanation of the Hilbert space formalism and its consequences to quantum physics.

The connection to the Hilbert spaces of wave functions is made as follows. If (a, b, … l, m, …) is a complete set of quantum numbers, denote the state corresponding to fixed choices of these quantum numbers by

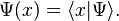

The wave function corresponding to an arbitrary state |Ψ⟩ is denoted

for a concrete example,

There are several advantages to understanding wave functions as representing elements of an abstract vector space:

- All the powerful tools of linear algebra can be used to manipulate and understand wave functions. For example:

- Linear algebra explains how a vector space can be given a basis, and then any vector in the vector space can be expressed in this basis. This explains the relationship between a wave function in position space and a wave function in momentum space, and suggests that there are other possibilities too.

- Bra–ket notation can be used to manipulate wave functions.

- The idea that quantum states are vectors in an abstract vector space (technically, a complex projective Hilbert space) is completely general in all aspects of quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, whereas the idea that quantum states are complex-valued "wave" functions of space is only true in certain situations.

Following is a summary of the bra–ket formalism applied to wave functions, with general discrete or continuous bases.

Discrete and continuous bases

A Hilbert space with a discrete basis |εi⟩ for i = 1, 2...n is orthonormal if the inner product of all pairs of basis kets are given by the Kronecker delta:

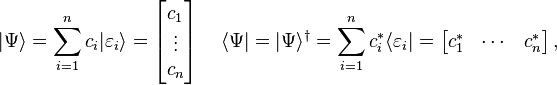

Orthonormal bases are convenient to work with because the inner product of two vectors have simple expressions. A wave function |Ψ⟩ expressed in this discrete basis of the Hilbert space, and the corresponding bra in the dual space, are respectively given by:

where the complex numbers

are the components of the vector. The column vector is a useful way to list the numbers, and operations on the entire vector can be done according to matrix addition and multiplication. The entire vector |Ψ⟩ is independent of the basis, but the components depend on the basis. If a change of basis is made, the components of the vector must also change to compensate.

A Hilbert space with a continuous basis { |ε⟩ } is orthonormal if the inner product of all pairs of basis kets are given by the Dirac delta function:

As with the discrete bases, a symbol ε is used in the basis states, two common notations are |ε⟩ and sometimes |Ψε⟩. A particular basis ket may be subscripted |ε0⟩ ≡ |Ψε0⟩ or primed |ε′⟩ ≡ |Ψε′⟩, or simply given another symbol in place of ε.

While discrete basis vectors are summed over a discrete index, continuous basis vectors are integrated over a continuous index (a variable of a function). In what follows, all integrals are with respect to the real-valued basis variable ε (not complex-valued), over the required range. Usually this is just the real line or subsets of it. The state |Ψ⟩ in the continuous basis of the Hilbert space, with the corresponding bra in the dual space, are respectively given by:[36]

where the components are the complex-valued functions

of a real variable ε.

Completeness conditions

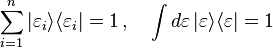

The completeness conditions (also called closure relations) are

for discrete and continuous orthonormal bases, respectively. An orthonormal set of kets form bases if and only if they satisfy these relations.[36] In each case, the equality to unity means this is an identity operator; its action on any state leaves it unchanged. Multiplying any state on the right of these gives the representation of the state |Ψ⟩ in the basis. The inner product of a first state |Ψ1⟩ with a second |Ψ2⟩ can also be obtained by multiplying |Ψ1⟩ on the left and |Ψ2⟩ on the right of the relevant completeness condition.

Inner product

Physically, the nature of the inner product is dependent on the basis in use, because the basis is chosen to reflect the quantum state of the system.

If |Ψ1⟩ is a state in the above basis with components c1, c2, ..., cn and |Ψ2⟩ is another state in the same basis with components z1, z2, ..., zn, the inner product is the complex number:

If |Ψ1⟩ is a state in the above continuous basis with components Ψ1(ε′), and |Ψ2⟩ is another state in the same basis with components Ψ2(ε), the inner product is the complex number:

where the integrals are taken over all ε and ε′.

The square of the norm (magnitude) of the state vector |Ψ⟩ is given by the inner product of |Ψ⟩ with itself, a real number:

for the discrete and continuous bases, respectively. Each say the projection of a complex probability amplitude onto itself is real. If |Ψ⟩ is normalized, these expressions would be each separately equal to 1. If the state is not normalized, then dividing by its magnitude normalizes the state:

Normalized components and probabilities

In the literature, the following results are often presented with normalized wave functions. Here, we keep the normalization factors to show where they appear if the wave function is not already normalized.

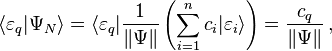

For the discrete basis, projecting the normalized state |ΨN⟩ onto a particular state the system may collapse to, |εq⟩, gives the complex number;

so the modulus squared of this gives a real number;

In the Copenhagen interpretation, this is the probability of state |εq⟩ occurring.

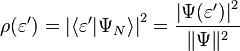

In the continuous basis, the projection of the normalized state onto some particular basis |ε′⟩ is a complex-valued function;

so the squared modulus is a real-valued function

In the Copenhagen interpretation, this function is the probability density function of measuring the observable ε′, so integrating this with respect to ε′ between a ≤ ε′ ≤ b gives:

the probability of finding the system with ε′ between ε′ = a and ε′ = b.

Wave function collapse

The physical meaning of the components of |Ψ⟩ is given by the wave function collapse postulate, also known as wave function collapse. If the observable(s) ε (momentum and/or spin, position and/or spin, etc.) corresponding to states |εi⟩ has distinct and definite values, λi, and a measurement of that variable is performed on a system in the state |Ψ⟩ then the probability of measuring λi is |⟨εi|Ψ⟩|2. If the measurement yields λi, the system "collapses" to the state |εi⟩ irreversibly and instantaneously.

Time dependence

In the Schrödinger picture, the states evolve in time, so the time dependence is placed in |Ψ⟩ according to[37]

for discrete bases, or

for continuous bases. However, in the Heisenberg picture the states |Ψ⟩ are constant in time and time dependence is placed in the Heisenberg operators, so |Ψ⟩ is not written as |Ψ(t)⟩. The Heisenberg picture wave function is a snapshot of a Schrödinger picture wave function, representing the whole spacetime history of the system. In the interaction picture (also called Dirac picture), the time dependence is placed in both the states and operators, the subdivision depending on the interaction term in the Hamiltonian, and can be viewed as intermediate between the Heisenberg and Schrödinger pictures. It is useful primarily in computing S-matrix elements.[38]

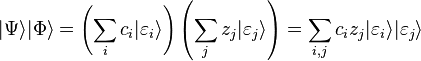

Tensor product

It is useful to introduce another operation with the physical interpretation of forming composite states from a collection of other states. This is the tensor product. Given two systems described by states |Ψ⟩ and |Φ⟩, the tensor product of the states forms the composite state denoted by |Ψ⟩⊗|Φ⟩ or simply without any operation symbol |Ψ⟩|Φ⟩, and the new system includes both of the original systems together. The tensor product state |Ψ⟩|Φ⟩ lives in a new space; the tensor product of the original Hilbert spaces. The bases spanning this space are the tensor products of the original bases. The product is not commutative in general, so |Ψ⟩|Φ⟩ ≠ |Φ⟩|Ψ⟩. If |Ψ⟩ has components ci and |Φ⟩ has components zj, each in a discrete orthonormal basis |εk⟩, then:

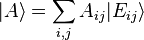

and the notation can be simplified by abbreviating |A⟩ = |Ψ⟩|Φ⟩, Aij = cizj, and |Eij⟩ = |εi⟩|εj⟩, so that

The same procedure follows for continuous bases using integration. This can also be extended to any number of states, however taking tensor products for fermions and bosons is complicated by the symmetry requirements, see identical particles for general results.

Position representations

This section applies mostly to non-relativistic quantum mechanics. In relativistic quantum mechanics, eigenstates of the position operator are problematic due to a relativistic extension of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle. In relativistic quantum field theory, they are not used at all to label physical states. Associated to a particle perfectly localized to a point in space is an infinite uncertainty in energy. This leads to pair production in the relativistic regime. Thus such a particle automatically has companions, leading to a breakdown of the description.

State space for one spin-0 particle in 1d

For a spinless particle in one spatial dimension (the x-axis or real line), the state |Ψ⟩ can be expanded in terms of a continuum of basis states; |x⟩, also written |Ψx⟩, corresponding to the set of all position coordinates x. The completeness condition for this basis is

and the orthogonality relation is

The state |Ψ⟩ is expressed by:

in which the "wave function" described as a function is a component of the complex state vector.

The inner product as stated at the beginning of this article is:

If the particle is confined to a region R (a subset of the x-axis), the integrals in the inner product and completeness condition would be integrals over R.

State space (other cases)

The previous example can be extended to more particles in higher dimensions, and include spin.

For one spinless particle in 3d, the basis states are |r⟩ and any state vector |Ψ⟩ in this space is expressed in terms of the basis vectors as |r⟩:

with components:

For N spinless particles in 3d, the basis states are |r1, ..., rN⟩. This is the tensor product of the one-particle position bases |r1⟩, |r2⟩, ..., |rN⟩, each of which spans the separate one-particle Hilbert spaces, so |r1, ..., rN⟩ are the basis states for the tensor product of the one-particle Hilbert spaces (the Hilbert space for the composite many particle system). Any state vector |Ψ⟩ in this space is

with components:

For one particle with spin in 3d, the basis states are |r, sz⟩, the tensor product of the position basis |r⟩ and spin basis |sz⟩, which exists in a new space from the spin space and position space alone. Any state |Ψ⟩ in this space is:

with components:

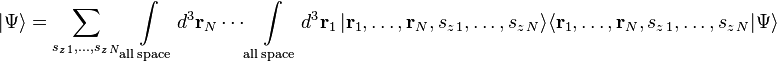

For N particles with spin in 3d, the basis states are |r1, ..., rN, sz 1, ..., sz N⟩, the tensor product of the position basis |r1, ..., rN⟩ and spin basis |sz 1, ..., sz N⟩, which exists in a new space from the spin space and position space alone. Any state in this space is:

with components:

If the particles are restricted to regions of position space, then the integrals in the completeness relations are taken over those regions, rather than the entire coordinate space. For the general case of many particles with spin in 3d, if particle 1 is in region R1, particle 2 is in region R2, and so on, the state in this position–spin representation is:

The orthogonality relation for this basis is:

and the inner product of |Ψ1⟩ and |Ψ2⟩ is:

Momentum space wave functions are similar, using the momentum vectors of the particles as continuous bases, namely |p⟩, |p1, p2, ..., pN⟩, etc.

Ontology

Whether the wave function really exists, and what it represents, are major questions in the interpretation of quantum mechanics. Many famous physicists of a previous generation puzzled over this problem, such as Schrödinger, Einstein and Bohr. Some advocate formulations or variants of the Copenhagen interpretation (e.g. Bohr, Wigner and von Neumann) while others, such as Wheeler or Jaynes, take the more classical approach[39] and regard the wave function as representing information in the mind of the observer, i.e. a measure of our knowledge of reality. Some, including Schrödinger, Bohm and Everett and others, argued that the wave function must have an objective, physical existence. Einstein thought that a complete description of physical reality should refer directly to physical space and time, as distinct from the wave function, which refers to an abstract mathematical space.[40]

Examples

Free particle

A free particle in 3d with wave vector k and angular frequency ω has a wave function

Particle in a box

A particle is restricted to a 1D region between x = 0 and x = L; its wave function is:

To normalize the wave function we need to find the value of the arbitrary constant A; solved from

From Ψ, we have |Ψ|2 = A2, so the integral becomes;

Solving this equation gives A = 1/√L, so the normalized wave function in the box is;

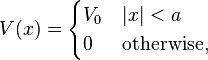

One-dimensional quantum tunnelling

The amplitudes and direction of left and right moving waves are indicated. In red, those waves used for the derivation of the reflection and transmission amplitude.

The amplitudes and direction of left and right moving waves are indicated. In red, those waves used for the derivation of the reflection and transmission amplitude.  for this illustration.

for this illustration.One of most prominent features of the wave mechanics is a possibility for a particle to reach a location with a prohibitive (in classical mechanics) force potential. In the one-dimensional case of particles with energy less than  in the square potential

in the square potential

the steady-state solutions to the wave equation have the form (for some constants  )

)

Note that these wave functions are not normalized; see scattering theory for discussion.

The standard interpretation of this is as a stream of particles being fired at the step from the left (the direction of negative x): setting Ar = 1 corresponds to firing particles singly; the terms containing Ar and Cr signify motion to the right, while Al and Cl – to the left. Under this beam interpretation, put Cl = 0 since no particles are coming from the right. By applying the continuity of wave functions and their derivatives at the boundaries, it is hence possible to determine the constants above.

Quantum Dots

In a semiconductor crystallite whose radius is smaller than the size of its exciton Bohr radius, the excitons are squeezed, leading to quantum confinement. The energy levels can then be modeled using the particle in a box model in which the energy of different states is dependent on the length of the box.

Other

Some examples of wave functions for specific applications include:

See also

- Boson

- de Broglie–Bohm theory

- Double-slit experiment

- Faraday wave

- Fermion

- Schrödinger equation

- Wave function collapse

- Wave packet

- Phase space formulation of quantum mechanics, wave functions are replaced by quasi-probability distributions that place the position and momenta variables on equal footing.

Remarks

- ↑ For this statement to make sense, the observables need to be elements of a complete commuting set. To see this, it is a simple matter to note that, for example, the momentum operator of the i'th particle in an n-particle system is not a generator of any symmetry in nature. On the other hand, the total angular momentum is a generator of a symmetry in nature; the translational symmetry.

- ↑ The resulting basis may or may not technically be a basis in the mathematical sense of Hilbert spaces. For instance, states of definite position and definite momentum are not square integrable. This may be overcome with the use of wave packets or by enclosing the system in a "box". See further remarks below.

- ↑ In technical terms, this is formulated the following way. The inner product yields a norm. This norm in turn induces a metric. If this metric is complete, then the aforementioned limits will be in the function space. The inner product space is then called complete. A complete inner product space is a Hilbert space. The abstract state space is always taken as a Hilbert space. The matching requirement for the function spaces is a natural one. The Hilbert space property of the abstract state space was originally extracted from the observation that the function spaces forming normalizable solutions to the Schrödinger equation are Hilbert spaces.

- ↑ As is explained in a later footnote, the integral must be taken to be the Lebesgue integral, the Riemann integral is not sufficient.

- ↑ One such relaxation is that the wave function must belong to the Sobolev space W1,2. It means that it is differentiable in the sense of distributions, and its gradient is square-integrable. This relaxation is necessary for potentials that are not functions but are distributions, such as the Dirac delta function.

- ↑ It is easy to visualize a sequence of functions meeting the requirement that converges to a discontinuous function. For this, modify an example given in Inner product space#Examples. This element though is an element of L2.

- ↑ For instance, in perturbation theory one may construct a sequence of functions approximating the true wave function. This sequence will be guaranteed to converge in a larger space, but without the assumption of a full-fledged Hilbert space, it will not be guaranteed that the convergence is to a function in the relevant space and hence solving the original problem.

- ↑ Some functions not being square-integrable, like the plane-wave free particle solutions are necessary for the description as outlined in a previous note and also further below.

- ↑ The Fourier transform viewed as a unitary operator on the space L2 has eigenvalues ±1, ±i. The eigenvectors are "Hermite functions", i.e. Hermite polynomials multiplied by a Gaussian function. See Byron & Fuller (1992) for a description of the Fourier transform as a unitary transformation. For eigenvalues and eigenvalues, refer to Problem 27 Ch. 9.

- ↑ The functions are here assumed to be elements of L2, the space of square integrable functions. The elements of this space are more precisely equivalence classes of square integrable functions, two functions declared equivalent if they differ on a set of Lebesgue measure 0. This is necessary to obtain an inner product (that is, (Ψ, Ψ) = 0 ⇒ Ψ ≡ 0) as opposed to a semi-inner product. The integral is taken to be the Lebesque integral. This is essential for completeness of the space, thus yielding a complete inner product space = Hilbert space.

Notes

- ↑ Born 1927, pp. 354–357

- ↑ Heisenberg 1958, p. 143

- ↑ Heisenberg, W. (1927/1985/2009). Heisenberg is translated by Camilleri 2009, p. 71, (from Bohr 1985, p. 142).

- ↑ Murdoch 1987, p. 43

- ↑ de Broglie 1960, p. 48

- ↑ Landau Lifshitz, p. 6

- ↑ Newton 2002, pp. 19–21

- 1 2 3 4 Born 1926a, translated in Wheeler & Zurek 1983 at pages 52–55.

- 1 2 Born 1926b, translated in Ludwig 1968, pp. 206–225. Also here.

- ↑ Born, M. (1954).

- ↑ Lerner & Trigg 1991, pp. 1223–1229

- ↑ Einstein 1905, pp. 132–148 (in German), Arons & Peppard 1965, p. 367 (in English)

- ↑ Einstein 1916, pp. 47–62 and a nearly identical version Einstein 1917, pp. 121–128 translated in ter Haar 1967, pp. 167–183.

- ↑ de Broglie 1923, pp. 507–510,548,630

- ↑ Hanle 1977, pp. 606–609

- ↑ Schrödinger 1926, pp. 1049–1070

- ↑ Tipler, Mosca & Freeman 2008

- 1 2 3 Weinberg 2013

- ↑ Young & Freedman 2008, p. 1333

- 1 2 3 Atkins 1974

- ↑ Martin & Shaw 2008

- ↑ Pauli 1927, pp. 601–623.

- ↑ Weinberg (2002) takes the standpoint that quantum field theory appears the way it does because it is the only way to reconcile quantum mechanics with special relativity.

- ↑ Weinberg (2002) See especially chapter 5, where some of these results are derived.

- ↑ Weinberg 2002 Chapter 4.

- ↑ Weinberg 2002

- ↑ Eisberg & Resnick 1985

- ↑ Rae 2008

- ↑ Atkins 1974, p. 258

- ↑ Shankar 1994, Ch. 1

- 1 2 Griffiths 2004

- ↑ Zettili 2009, p. 463

- ↑ Shankar 1994, p. 378–379

- ↑ Dirac 1982

- ↑ Dirac 1939

- 1 2 (Peleg et al. 2010) pp. 64–65.

- ↑ (Peleg et al. 2010, pp. 68–69)

- ↑ Weinberg 2002 Chapter 3, Scattering matrix.

- ↑ Jaynes 2003

- ↑ Einstein 1998, p. 682

References

- Atkins, P. W. (1974). Quanta: A Handbook of Concepts. ISBN 0-19-855494-X.

- Arons, A. B.; Peppard, M. B. (1965). "Einstein's proposal of the photon concept: A translation of the Annalen der Physik paper of 1905" (PDF). American Journal of Physics 33 (5): 367. Bibcode:1965AmJPh..33..367A. doi:10.1119/1.1971542.

- Bohr, N. (1985). J. Kalckar, ed. Niels Bohr - Collected Works: Foundations of Quantum Physics I (1926 - 1932) 6. Amsterdam: North Holland. ISBN 9780444532893.

- Born, M. (1926a). "Zur Quantenmechanik der Stoßvorgange". Z. Phys. 37: 863–867. Bibcode:1926ZPhy...37..863B. doi:10.1007/bf01397477.

- Born, M. (1926b). "Quantenmechanik der Stoßvorgange". Z. Phys. 38: 803–827. Bibcode:1926ZPhy...38..803B. doi:10.1007/bf01397184.

- Born, M. (1927). "Physical aspects of quantum mechanics". Nature 119: 354–357. Bibcode:1927Natur.119..354B. doi:10.1038/119354a0.

- Born, M. (1954). "The statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics" (PDF). Nobel Lecture. December 11, 1954.

- de Broglie, L. (1923). "Radiations—Ondes et quanta" [Radiation—Waves and quanta]. Comptes Rendus (in French) 177: 507–510, 548, 630. Online copy (French) Online copy (English)

- de Broglie, L. (1960). Non-linear Wave Mechanics: a Causal Interpretation. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Camilleri, K. (2009). Heisenberg and the Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics: the Physicist as Philosopher. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88484-6.

- Byron, F. W.; Fuller, R. W. (1992) [1969]. Mathematics of Classical and Quantum Physics. Dover Books on Physics (revised ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-67164-2.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1982). The principles of quantum mechanics. The international series on monographs on physics (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0 19 852011 5.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1939). "A new notation for quantum mechanics". Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 35 (3): 416–418. Bibcode:1939PCPS...35..416D. doi:10.1017/S0305004100021162.

- Einstein, A. (1905). "Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt". Annalen der Physik (in German) 17 (6): 132–148. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..132E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220607.

- Einstein, A. (1916). "Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung". Mitteilungen der Physikalischen Gesellschaft Zürich 18: 47–62.

- Einstein, A. (1917). "Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung". Physikalische Zeitschrift (in German) 18: 121–128. Bibcode:1917PhyZ...18..121E.

- Einstein, A. (1998). P. A. Schlipp, ed. Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist. The Library of Living Philosophers VII (3rd ed.). La Salle Publishing Company, Illinois: Open Court. ISBN 0-87548-133-7.

- Eisberg, R.; Resnick, R. (1985). Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0.

- Griffiths, D. J. (2004). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Essex England: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 978-0131118928.

- Heisenberg, W. (1958). Physics and Philosophy: the Revolution in Modern Science. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hanle, P.A. (1977), "Erwin Schrodinger's Reaction to Louis de Broglie's Thesis on the Quantum Theory.", Isis 68 (4), doi:10.1086/351880

- Jaynes, E. T. (2003). G. Larry Bretthorst, ed. Probability Theory: The Logic of Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521 59271-0.

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1977). Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory. Vol. 3 (3rd ed.). Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-020940-1. Online copy

- Lerner, R.G.; Trigg, G.L. (1991). Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). VHC Publishers. ISBN 0-89573-752-3.

- Ludwig, G. (1968). Wave Mechanics. Oxford UK: Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-203204-1. LCCN 66-30631.

- Murdoch, D. (1987). Niels Bohr's Philosophy of Physics. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33320-2.

- Newton, R.G. (2002). Quantum Physics: a Text for Graduate Student. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-95473-2.

- Pauli, Wolfgang (1927). "Zur Quantenmechanik des magnetischen Elektrons". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German) 43. Bibcode:1927ZPhy...43..601P. doi:10.1007/bf01397326.

- Peleg, Y.; Pnini, R.; Zaarur, E.; Hecht, E. (2010). Quantum mechanics. Schaum's outlines (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-162358-2.

- Rae, A.I.M. (2008). Quantum Mechanics 2 (5th ed.). Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 1-5848-89705.

- Schrödinger, E. (1926). "An Undulatory Theory of the Mechanics of Atoms and Molecules" (PDF). Physical Review 28 (6): 1049–1070. Bibcode:1926PhRv...28.1049S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.28.1049. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008.

- Shankar, R. (1994). Principles of Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). ISBN 0306447908.

- Martin, B.R.; Shaw, G. (2008). Particle Physics. Manchester Physics Series (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-03294-7.

- ter Haar, D. (1967). The Old Quantum Theory. Pergamon Press. pp. 167–183. LCCN 66029628.

- Tipler, P. A.; Mosca, G.; Freeman (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers – with Modern Physics (6th ed.). ISBN 0-7167-8964-7.

- Weinberg, S. (2013), Lectures in Quantum Mechanics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-02872-2

- Weinberg, S. (2002), The Quantum Theory of Fields 1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55001-7

- Young, H. D.; Freedman, R. A. (2008). Pearson, ed. Sears' and Zemansky's University Physics (12th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-50130-1.

- Wheeler, J.A.; Zurek, W.H. (1983). Quantum Theory and Measurement. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Zettili, N. (2009). Quantum Mechanics: Concepts and Applications (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0-470-02679-3.

Further reading

- Yong-Ki Kim (September 2, 2000). "Practical Atomic Physics" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology (Maryland): 1 (55 pages). Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- Polkinghorne, John (2002). Quantum Theory, A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280252-6.

External links

- , , ,

- Normalization.

- Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Computation at BerkeleyX

- Einstein, The quantum theory of radiation