Wave function collapse

In quantum mechanics, wave function collapse is said to occur when a wave function—initially in a superposition of several eigenstates—appears to reduce to a single eigenstate (by "observation"). It is the essence of measurement in quantum mechanics and connects the wave function with classical observables such as position and momentum. Collapse is one of two ways in which quantum systems change; the other is continuous evolution via the Schrödinger equation.[1] However, in this role, collapse is merely a black box for thermodynamically irreversible interaction with a classical environment.[2][3]

Calculations of quantum decoherence predict apparent wave function collapse when a superposition forms between the quantum system's states and the environment's states. It amounts to local suppression of interference through interaction with the measuring apparatus environment typically leading to a rapid vanishing of the diagonal terms in the local density matrix describing the probability distribution for the outcomes of measurements on the system. Significantly, the combined wave function of the system and environment continue to obey the Schrödinger equation.[4]

In 1927, Werner Heisenberg used the idea of wave function reduction to explain quantum measurement.[5] Nevertheless, it was debated, for if collapse were a fundamental physical phenomenon, rather than just the epiphenomenon of some other process, it would mean nature was fundamentally nondeterministic, an undesirable property for a theory.[2][6] This issue remained until quantum decoherence entered mainstream opinion after its reformulation in the 1980s.[2][4][7]

Decoherence explains the perception of wave function collapse in terms of interacting large- and small-scale quantum systems, and is commonly taught at the graduate level, e.g., Bes.[8]

Mathematical description

Before collapse, the wave function may be any square-integrable function. This function is expressible as a linear combination of the eigenstates of any observable. Observables represent classical dynamical variables, and when one is measured by a classical observer, the wave function is projected onto a random eigenstate of that observable. The observer simultaneously measures the classical value of that observable to be the eigenvalue of the final state.[9]

According to ordinary quantum mechanics, however, it is actually a matter of complete indifference whether the experimenters stay around to watch their experiment, or leave the room and delegate observing to an inanimate apparatus, which amplifies the microscopic events to macroscopic measurements and records them by a time-irreversible process.[10] The measured state is not interfering with the states excluded by the measurement.

As Richard Feynman put it succinctly: "Nature does not know what you are looking at, and she behaves the way she is going to behave whether you bother to take down the data or not."[11]

Mathematical background

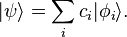

The quantum state of a physical system is described by a wave function (in turn – an element of a projective Hilbert space). This can be expressed in Dirac or bra–ket notation as a vector:

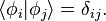

The kets  , specify the different quantum "alternatives" available - a particular quantum state. They form an orthonormal eigenvector basis, formally

, specify the different quantum "alternatives" available - a particular quantum state. They form an orthonormal eigenvector basis, formally

Where  represents the Kronecker delta.

represents the Kronecker delta.

An observable (i.e. measurable parameter of the system) is associated with each eigenbasis, with each quantum alternative having a specific value or eigenvalue, ei, of the observable. A "measurable parameter of the system" could be the usual position r and the momentum p of (say) a particle, but also its energy E, z-components of spin (sz), orbital (Lz) and total angular (Jz) momenta etc. In the basis representation these are respectively  .

.

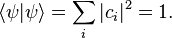

The coefficients c1, c2, c3... are the probability amplitudes corresponding to each basis  . These are complex numbers. The moduli square of ci, that is |ci|2 = ci*ci (* denotes complex conjugate), is the probability of measuring the system to be in the state

. These are complex numbers. The moduli square of ci, that is |ci|2 = ci*ci (* denotes complex conjugate), is the probability of measuring the system to be in the state  .

.

For simplicity in the following, all wave functions are assumed to be normalized; the total probability of measuring all possible states is unity:

The process

With these definitions it is easy to describe the process of collapse. For any observable, the wave function is initially some linear combination of the eigenbasis  of that observable. When an external agency (an observer, experimenter) measures the observable associated with the eigenbasis

of that observable. When an external agency (an observer, experimenter) measures the observable associated with the eigenbasis  , the wave function collapses from the full

, the wave function collapses from the full  to just one of the basis eigenstates,

to just one of the basis eigenstates,  , that is:

, that is:

The probability of collapsing to a given eigenstate  is the Born probability,

is the Born probability,  . Post-measurement, other elements of the wave function vector,

. Post-measurement, other elements of the wave function vector,  , have "collapsed" to zero, and

, have "collapsed" to zero, and  .

.

More generally, collapse is defined for an operator  with eigenbasis

with eigenbasis  . If the system is in state

. If the system is in state  , and

, and  is measured, the probability of collapsing the system to state

is measured, the probability of collapsing the system to state  (and measuring

(and measuring  ) would be

) would be  . Note that this is not the probability that the particle is in state

. Note that this is not the probability that the particle is in state  ; it is in state

; it is in state  until cast to an eigenstate of

until cast to an eigenstate of  .

.

However, we never observe collapse to a single eigenstate of a continuous-spectrum operator (e.g. position, momentum, or a scattering Hamiltonian), because such eigenfunctions are non-normalizable. In these cases, the wave function will partially collapse to a linear combination of "close" eigenstates (necessarily involving a spread in eigenvalues) that embodies the imprecision of the measurement apparatus. The more precise the measurement, the tighter the range. Calculation of probability proceeds identically, except with an integral over the expansion coefficient  .[12] This phenomenon is unrelated to the uncertainty principle, although increasingly precise measurements of one operator (e.g. position) will naturally homogenize the expansion coefficient of wave function with respect to another, incompatible operator (e.g. momentum), lowering the probability of measuring any particular value of the latter.

.[12] This phenomenon is unrelated to the uncertainty principle, although increasingly precise measurements of one operator (e.g. position) will naturally homogenize the expansion coefficient of wave function with respect to another, incompatible operator (e.g. momentum), lowering the probability of measuring any particular value of the latter.

Interpretations

The determination of preferred-basis

The complete set of orthogonal functions which a wave function will collapse to is also called preferred-basis.[2] There lacks theoretical foundation for the preferred-basis to be the eigenstates of observables such as position, momentum, etc. In fact the eigenstates of position are not even physical due to the infinite energy associated with them. A better approach is to derive the preferred-basis from basic principles. It is proved that only special dynamic equation can collapse the wave function.[13] By applying one axiom of the quantum mechanics and the assumption that preferred-basis depends on the total Hamiltonian, a unique set of equations is obtained from the collapse equation which determines the preferred-basis for general situations. Depending on the system Hamiltonian and wave function, the determination equations may yield preferred-basis as energy eigenfunctions, quasi-position eigenfunctions, mixed energy and quasi-position eigenfunctions, i.e., energy eigenfunctions for the interior of a macroscopic object and quasi-position eigenfunctions for the particles on the surface, and so on.

Quantum decoherence

Wave function collapse is not fundamental from the perspective of quantum decoherence.[14] There are several equivalent approaches to deriving collapse, like the density matrix approach, but each has the same effect: decoherence irreversibly converts the "averaged" or "environmentally traced over" density matrix from a pure state to a reduced mixture, giving the appearance of wave function collapse.

Quantum filtering approach

The quantum filtering approach[15][16][17] and the introduction of quantum causality non-demolition principle[18] allows for a classical-environment derivation of wave function collapse from the stochastic Schrödinger equation.

History and context

The concept of wavefunction collapse, under the label 'reduction', not 'collapse', was introduced by Werner Heisenberg in his 1927 paper on the uncertainty principle, "Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematic und Mechanik".[5] Heisenberg's notion of 'reduction' was mentioned by Max Born at the 1927 Solvay conference.[19] The concept of reduction was more clearly expressed in Heisenberg's 1930 textbook.[20]

A version of the concept, without the use of the word 'collapse', was incorporated into the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics by John von Neumann, in his 1932 treatise Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik.[21] Consistent with Heisenberg, von Neumann postulated that there were two processes of wave function change:

- The probabilistic, non-unitary, discontinuous change brought about by observation and measurement, as outlined above.

- The deterministic, unitary, continuous time evolution of an isolated system that obeys the Schrödinger equation.

Instead of Heisenberg's term 'reduction', the term 'collapse' was used by Bohm in his 1951 textbook.[22]

In general, quantum systems exist in superpositions of those basis states that most closely correspond to classical descriptions, and, in the absence of measurement, evolve according to the Schrödinger equation. However, when a measurement is made, the wave function collapses—from an observer's perspective—to just one of the basis states, and the property being measured uniquely acquires the eigenvalue of that particular state,  . After the collapse, the system again evolves according to the Schrödinger equation.

. After the collapse, the system again evolves according to the Schrödinger equation.

By explicitly dealing with the interaction of object and measuring instrument, von Neumann[1] has attempted to create consistency of the two processes of wave function change.

He was able to prove the possibility of a quantum mechanical measurement scheme consistent with wave function collapse. However, he did not prove the necessity of such a collapse. Although von Neumann's projection postulate is often presented as a normative description of quantum measurement, it was conceived by taking into account experimental evidence available during the 1930s (in particular the Compton-Simon experiment was paradigmatic), but many important present-day measurement procedures do not satisfy it (so-called measurements of the second kind).[23][24][25]

The existence of the wave function collapse is required in

- the Copenhagen interpretation

- the objective collapse interpretations

- the transactional interpretation

- the von Neumann interpretation in which consciousness causes collapse.

On the other hand, the collapse is considered a redundant or optional approximation in

- the Consistent histories approach, self-dubbed "Copenhagen done right"

- the Bohm interpretation

- the Many-worlds interpretation

- the Ensemble Interpretation

The cluster of phenomena described by the expression wave function collapse is a fundamental problem in the interpretation of quantum mechanics, and is known as the measurement problem. The problem is deflected by the Copenhagen Interpretation, which postulates that this is a special characteristic of the "measurement" process. Everett's many-worlds interpretation deals with it by discarding the collapse-process, thus reformulating the relation between measurement apparatus and system in such a way that the linear laws of quantum mechanics are universally valid; that is, the only process according to which a quantum system evolves is governed by the Schrödinger equation or some relativistic equivalent.

Originating from de Broglie–Bohm theory, but no longer tied to it, is the physical process of decoherence, which causes an apparent collapse. Decoherence is also important for the consistent histories interpretation. A general description of the evolution of quantum mechanical systems is possible by using density operators and quantum operations. In this formalism (which is closely related to the C*-algebraic formalism) the collapse of the wave function corresponds to a non-unitary quantum operation.

The significance ascribed to the wave function varies from interpretation to interpretation, and varies even within an interpretation (such as the Copenhagen Interpretation). If the wave function merely encodes an observer's knowledge of the universe then the wave function collapse corresponds to the receipt of new information. This is somewhat analogous to the situation in classical physics, except that the classical "wave function" does not necessarily obey a wave equation. If the wave function is physically real, in some sense and to some extent, then the collapse of the wave function is also seen as a real process, to the same extent.

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Wave function collapse |

- Arrow of time

- Interpretations of quantum mechanics

- Quantum decoherence

- Quantum interference

- Quantum Zeno effect

- Schrödinger's cat

- Stern–Gerlach experiment

- Observer effect (physics)

References

- 1 2 J. von Neumann (1932). Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik (in German). Berlin: Springer.

- J. von Neumann (1955). Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Schlosshauer, Maximilian (2005). "Decoherence, the measurement problem, and interpretations of quantum mechanics". Rev. Mod. Phys. 76 (4): 1267–1305. arXiv:quant-ph/0312059. Bibcode:2004RvMP...76.1267S. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.76.1267. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Giacosa, Francesco (2014). "On unitary evolution and collapse in quantum mechanics". Quanta 3 (1): 156–170. doi:10.12743/quanta.v3i1.26.

- 1 2 Zurek, Wojciech Hubert (2009). "Quantum Darwinism". Nature Physics 5: 181–188. arXiv:0903.5082. Bibcode:2009NatPh...5..181Z. doi:10.1038/nphys1202. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- 1 2 Heisenberg, W. (1927). Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik, Z. Phys. 43: 172–198. Translation as 'The actual content of quantum theoretical kinematics and mechanics' here, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ L. Bombelli. "Wave-Function Collapse in Quantum Mechanics". Topics in Theoretical Physics. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ↑ M. Pusey, J. Barrett, T. Rudolph (2012). "On the reality of the quantum state" (PDF).

- ↑ Daniel R Bes (2004). Quantum Mechanics: A Modern and Concise Introductory Course, (Advanced Texts in Physics) Springer (June 14, 2004), ISBN 3540203656

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (2005). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 2e. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 106–109. ISBN 0131118927.

- ↑ Bell, John (2004). Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics: Collected Papers on Quantum Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 9780521523387.

- ↑ Feynman, Richard (2015). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. III. Ch 3.2: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465040834.

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (2005). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 2e. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 100–105. ISBN 0131118927.

- ↑ S. Mei (2013). "on the origin of preferred-basis and evolution pattern of wave function" (PDF).

- ↑ Wojciech H. Zurek, Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical,Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75, 715 or http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0105127

- ↑ V. P. Belavkin (1979). Optimal Measurement and Control in Quantum Dynamical Systems (Technical report). Copernicus University, Toruń. pp. 3–38. arXiv:quant-ph/0208108. 411.

- ↑ V. P. Belavkin (1992). "Quantum stochastic calculus and quantum nonlinear filtering". Journal of Multivariate Analysis 42 (2): 171–201. arXiv:math/0512362. doi:10.1016/0047-259X(92)90042-E.

- ↑ V. P. Belavkin (1999). "Measurement, filtering and control in quantum open dynamical systems". Reports on Mathematical Physics 43 (3): A405–A425. arXiv:quant-ph/0208108. Bibcode:1999RpMP...43..405B. doi:10.1016/S0034-4877(00)86386-7.

- ↑ V. P. Belavkin (1994). "Nondemolition principle of quantum measurement theory". Foundations of Physics 24 (5): 685–714. arXiv:quant-ph/0512188. Bibcode:1994FoPh...24..685B. doi:10.1007/BF02054669.

- ↑ Électrons et Photons: Rapports et Discussions du Cinquième Conseil de Physique, tenu à Bruxelles du 24 au 29 Octobre 1927, sous les Auspices de l'Institut International de Physique Solvay, Gauthier-Villars, Paris, p. 251, translated in Bacciagaluppi, G., Valentini, A, (2009). Quantum Theory at the Crossroads: Reconsidering the 1927 Solvay Conference, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, ISBN 978-0-521-81421-8, p. 482.

- ↑ Heisenberg, W. (1930). The Physical Principles of the Quantum Theory, translated by C. Eckart and F.C. Hoyt, University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL, p. 39.

- ↑ C. Kiefer (2002). "On the interpretation of quantum theory – from Copenhagen to the present day". arXiv:quant-ph/0210152 [quant-ph].

- ↑ Bohm, D. (1951). Quantum Theory, Prentice–Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, p. 120.

- ↑ W. Pauli (1958). "Die allgemeinen Prinzipien der Wellenmechanik". In S. Flügge. Handbuch der Physik (in German) V. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 73.

- ↑ L. Landau and R. Peierls (1931). "Erweiterung des Unbestimmtheitsprinzips für die relativistische Quantentheorie". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German) 69 (1-2): 56. Bibcode:1931ZPhy...69...56L. doi:10.1007/BF01391513.)

- ↑ Discussions of measurements of the second kind can be found in most treatments on the foundations of quantum mechanics, for instance, J. M. Jauch (1968). Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Addison-Wesley. p. 165.; B. d'Espagnat (1976). Conceptual Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. W. A. Benjamin. pp. 18, 159.; and W. M. de Muynck (2002). Foundations of Quantum Mechanics: An Empiricist Approach. Kluwer Academic Publishers. section 3.2.4..