Watts riots

| Watts riots | |

|---|---|

|

Burning buildings during the riots | |

| Date | August 11–17, 1965 |

| Location | Watts, Los Angeles, California United States |

| Methods | Widespread rioting, looting, assault, arson, protests, firefights, property damage, murder |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 34 |

| Injuries | 1,032 |

| Arrested | 3,438 |

The Watts riots (or, collectively, Watts rebellion)[1] took place in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles from August 11 to 17, 1965.

On August 11, 1965, a black motorist was arrested for drunk driving. A minor roadside argument broke out, and then escalated into a fight. The community reacted in outrage. Six days of looting and arson, especially of white-owned businesses, followed. Los Angeles police needed the support of nearly 4,000 members of the California Army National Guard to quell the riots, which resulted in 34 deaths and over $40 million in property damage. The riots were blamed principally on unemployment, although a later investigation also highlighted police racism. It was the city's worst unrest until the Rodney King riots of 1992.

Background

In the Great Migration of the 1920s, major populations of African-Americans moved to Northern and Midwestern cities like Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Boston, and New York City to pursue jobs in newly established manufacturing industries; to establish better educational and social opportunities; and to flee racial segregation, Jim Crow Laws, violence, and racial bigotry in the Southern States. This wave of migration largely bypassed Los Angeles. In the 1940s, in the Second Great Migration, black Americans migrated to the West Coast in large numbers, in response to defense industry recruitment efforts at the start of World War II. The black population in Los Angeles leapt from approximately 63,700 in 1940 to about 350,000 in 1965, making the once-small black community visible to the general public.[2]

Residential segregation

Los Angeles did not have the outright de jure segregation that the South did, but it still had racial restrictive covenants that prevented blacks and Latinos from renting and buying in certain areas, even long after the courts ruled them illegal in 1948. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Los Angeles has been geographically divided by ethnicity. In the 1920s, the city was the location of the first racially restrictive covenants in real estate. By the Second World War, 95% of Los Angeles housing was off-limits to African Americans and Asians. Minorities who had served in World War II or worked in L.A.'s defense industries returned to face increasing patterns of discrimination in housing. In addition, they found themselves excluded from the suburbs and restricted to housing in East or South Los Angeles, which includes the Watts neighborhood and Compton. Such real-estate practices severely restricted educational and economic opportunities available to the minority community.

With an influx of black residents, housing in South Los Angeles became increasingly scarce, overwhelming the already established communities and providing opportunities for real estate developers. Davenport Builders, for example, was a large developer who responded to the demand, with an eye on undeveloped land in Compton. What was originally a mostly white neighborhood in the 1940s increasingly became an African American, middle-class dream in which blue-collar laborers could enjoy suburbia away from the slums. These new housing developments provided better ways of life with more space for families to grow and enjoy healthy living.

For a time in the early 1950s, with its increasing numbers of African Americans, South Los Angeles became the site of significant racial violence. In the area south of Slauson Avenue, whites bombed or fired into houses and set crosses burning on the lawns of homes purchased by black families. In an escalation of behavior that began in the 1920s, white gangs in nearby cities such as South Gate and Huntington Park routinely accosted blacks who traveled through white areas.

Suburbs in the Los Angeles area grew explosively. Most of these suburbs barred black people using a variety of methods. This provided an opportunity for white people in neighborhoods bordering black districts to leave en masse to the suburbs. The spread of African Americans throughout urban Los Angeles was achieved in large part through blockbusting, a technique whereby real estate speculators would buy a home on an all-white street, sell or rent it to a black family, and then buy up the remaining homes from Caucasians at cut-rate prices, then sell them to housing-hungry black families at hefty profits.

The Rumford Fair Housing Act, designed to remedy residential segregation, was overturned by Proposition 14, which was sponsored by the California real estate industry, and supported by a majority of white voters. Psychiatrist and civil rights activist Alvin Poussaint considered Proposition 14 to be one of the root causes of black rebellion in Watts.[3]

Police discrimination

Los Angeles's black and Latino residents were excluded from the high-paying jobs, affordable housing, and politics available to white residents. Additionally, they also faced discrimination by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). In 1950, William H. Parker was appointed and sworn in as Los Angeles Chief of Police. After a major scandal called Bloody Christmas of 1951, Parker pushed for more independence from political pressures that would enable him to create a more professionalized police force. The public supported him and voted for charter changes that isolated the police department from the rest of government. In the 1960s, the LAPD was promoted as one of the best police forces in the world.

Despite its reform and having a professionalized, military-like police force, William Parker's LAPD faced heavy criticism from the city's Latino and black residents for police brutality. Chief Parker coined the term "Thin Blue Line."[4]

There are, therefore, some who would argue that racial injustices caused Watts's African-American population to explode on August 11, 1965 in what would become the Watts Rebellion.[5]

Inciting incident

On the evening of Wednesday, August 11, 1965, 21-year-old Marquette Frye, an African American man behind the wheel of his mother's 1955 Buick, was pulled over for reckless driving by white California Highway Patrol motorcycle officer Lee Minikus.[6] After administering a field sobriety test, Minikus placed Frye under arrest and radioed for his vehicle to be impounded.[7] Marquette's brother Ronald, a passenger in the vehicle, walked to their house nearby, bringing their mother, Rena Price, back with him.

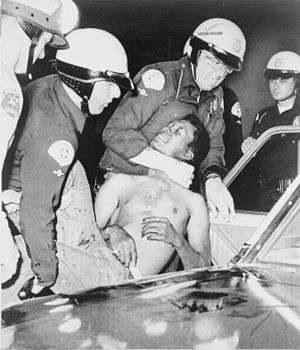

When Rena Price reached the intersection of Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street that evening, she scolded Frye about drinking and driving, as he recalled in a 1985 interview with the Orlando Sentinel.[8] The situation quickly escalated: Someone shoved Price, Frye was struck, Price jumped an officer, and another officer pulled out a shotgun. Backup police officers attempted to arrest Frye by using physical force to subdue him. After rumors spread that the police had roughed up Frye and kicked a pregnant woman, angry mobs formed.[9][10] As the situation intensified, growing crowds of local residents watching the exchange began yelling and throwing objects at the police officers.[11] Frye's mother and brother fought with the officers and were eventually arrested along with Marquette Frye.[12][13]

After the arrests of Price and the Frye brothers, the crowd continued to grow. Police came to the scene to break up the crowd several times that night, but were attacked by rocks and concrete.[14] A 119-square-kilometer (46-square-mile) swath of Los Angeles would be transformed into a combat zone during the ensuing six days.[15]

The riot begins

After a night of increasing unrest, police and local black community leaders held a community meeting on Thursday, August 12, to discuss an action plan and to urge calm. The meeting failed. Later that day, Los Angeles police chief William H. Parker called for the assistance of the California Army National Guard.[16]

The rioting intensified, and on Friday, August 13, about 2,300 National Guardsmen joined the police in trying to maintain order on the streets. By midnight on Saturday, August 14, an additional 1,600 National Guardsmen had joined the efforts to quell the riots. Sergeant Ben Dunn said: "The streets of Watts resembled an all-out war zone in some far-off foreign country, it bore no resemblance to the United States of America." Following the deployment of National Guardsmen, a curfew was declared for a vast region of South Central Los Angeles.[17] In addition to the Guardsmen, 934 Los Angeles Police officers and 718 officers from the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department were deployed during the rioting.[16]

Between 31,000 and 35,000 adults participated in the riots over the course of six days, while about 70,000 people were "sympathetic, but not active."[14] Over the six days, there were 34 deaths,[18][19] 1,032 injuries,[18][20] 3,438 arrests,[18][21] and over $40 million in property damage.[18] White Americans were fearful of the breakdown of social order in Watts, especially since white motorists were being pulled over by rioters in nearby areas and assaulted.[22] Many in the black community, however, saw the rioters as taking part in an "uprising against an oppressive system."[14] In a 1966 essay, black civil rights activist Bayard Rustin stated: "The whole point of the outbreak in Watts was that it marked the first major rebellion of Negroes against their own masochism and was carried on with the express purpose of asserting that they would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life."[23]

Those actively participating in the riots started physical fights with police, blocked firefighters of the Los Angeles Fire Department from their safety duties, or beat white motorists. Arson and looting were largely confined to white-owned stores and businesses that were said to have caused resentment in the neighborhood due to perceived unfairness.[24]

Los Angeles police chief Parker publicly stated that the people he saw rioting were acting like "monkeys in the zoo."[24] Overall, an estimated $40 million in damage was caused, with almost 1,000 buildings damaged or destroyed. Homes were not attacked, although some caught fire due to proximity to other fires.

| Businesses and private buildings | Public buildings | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Damaged/burned: 258 | Damaged/burned: 14 | Total: 272 |

| Looted: 192 | Total: 192 | |

| Both damaged/burned & looted: 288 | Total: 288 | |

| Destroyed: 267 | Destroyed: 1 | Total: 268 |

Post-riot commentary

Debates have surfaced over what really happened in Watts, as the area was known to be under a great deal of racial and social tension. Reactions and reasoning about the Watts incident greatly varied based on the perspectives of those affected by and participating in the riots' chaos. A commission under Governor Pat Brown investigated the riots. The McCone Commission, headed by former CIA director John A. McCone, released a 101-page report on December 2, 1965 entitled Violence in the City—An End or a Beginning?: A Report by the Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, 1965.[25]

The report identified the root causes of the riots to be high unemployment, poor schools, and other inferior living conditions for African Americans in Watts. Recommendations for addressing these problems included "emergency literacy and preschool programs, improved police-community ties, increased low-income housing, more job-training projects, upgraded health-care services, more efficient public transportation, and many more." Most of these recommendations were not acted upon.[26]

More opinions and explanations appeared as other sources attempted to explain the causes. Public opinion polls have shown that an equal percentage of people believed that the riots were linked to communist groups versus those that blamed social problems like unemployment and prejudice.[27] Those opinions concerning racism and discrimination emerged only three years after hearings conducted by a committee of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights took place in Los Angeles to assess the condition of relations between the police force and minorities. These hearings were also intended to make a ruling on the discrimination case against the police for their alleged mistreatment of members of the Nation of Islam.[27] These different arguments and opinions still prompt debates over the underlying causes of the Watts riots.[24]

Martin Luther King Jr. spoke two days after the riots happened in Watts. The riots were also a response to Proposition 14, a constitutional amendment sponsored by the California Real Estate Association that had in effect repealed the Rumford Fair Housing Act.[28] In 1966, the California Supreme Court reinstated the Rumford Fair Housing Act in the Reitman v. Mulkey case (a decision affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court the following year).

Marquette Frye, who smoked and drank heavily, died of pneumonia on December 20, 1986 at age 42.[29] His mother, Rena Price, died on June 10, 2013, at 97.[30] She never recovered the impounded 1955 Buick in which her son had been pulled over for driving while intoxicated on August 11, 1965, because the storage fees exceeded the car's value.[31]

Cultural references

- The Hughes brothers film Menace II Society (1993) opens with images taken from the riots of 1965. The entire film is set in Watts from the 1970s to the 1990s.

- Frank Zappa wrote a lyrical commentary inspired by the Watts riots, entitled "Trouble Every Day". It contains such lines as "Wednesday I watched the riot / Seen the cops out on the street / Watched 'em throwin' rocks and stuff /And chokin' in the heat". The song was released on his debut album Freak Out! (with the original Mothers of Invention), and later slightly rewritten as "More Trouble Every Day", available on Roxy and Elsewhere and The Best Band You Never Heard In Your Life.

- Phil Ochs' 1965 song "In the Heat of the Summer", most famously recorded by Judy Collins, was a chronicle of the Watts Riots.

- Curt Gentry's 1968 novel, The Last Days of the Late, Great State of California, dissected the riots in detail in a fact-based semi-documentary tone.

- Charles Bukowski mentioned the Watts riots in his poem "Who in the hell is Tom Jones?"

- The 1990 film Heat Wave depicts the Watts riots from the perspective of journalist Bob Richardson as a resident of Watts and a reporter for the Los Angeles Times.

- The 1994 film There Goes My Baby tells the story of a group of high school seniors during the riots.

- The producers of the Planet of the Apes franchise stated that the riots were the inspiration for the ape uprising in the film Conquest of the Planet of the Apes.[32]

- In "Black on White on Fire", the November 9, 1990 episode of the television series Quantum Leap Sam Beckett leaps into the body of a black man who is engaged to a white woman while living in Watts during the riots.

- Scenes in "Burn, Baby, Burn", an episode of the TV series Dark Skies, takes place in Los Angeles during the riots.

- The movie C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America mentions the Watts riots as a slave rebellion rather than a riot.

- Walter Mosley's novel Little Scarlet, in which Mosley's recurring character Easy Rawlins is asked by police to investigate a racially charged murder in neighborhoods where white investigators are unwelcome, takes place during the Watts riots.

- The riots are depicted in the third issue of the Before Watchmen: Comedian comic book, including a scene in which The Comedian throws dog feces into the face of Police Chief Parker.

- The riots are referenced in the 2000 film Remember the Titans, when an Alexandria, Virginia school board representative explains to former head football coach Bill Yoast that he would be replaced by Herman Boone, an African American coach from North Carolina, because the school board feared that otherwise, Alexandria would "...burn up like Watts".

- In Chapter 9 of "A Song Flung Up To Heaven", the sixth volume of Maya Angelou's autobiography, Angelou gives an account of the riots. She had a job in the neighborhood at the time and experienced the riots first-hand.

- Joseph Wambaugh's novel The New Centurions is partially set during the Watts riots.

- Gary Phillips' novel Violent Spring is set in the Watts riots.

- The arrest of the Fryes and the ensuing riots are referenced by the character George Hutchence in the second volume of the comics miniseries Jupiter's Circle, as an example of the class struggle that he felt he had been perpetuating as a superhero, and which prompted him to give up that life.[33]

See also

- 1992 Los Angeles riots

- History of the African-Americans in Los Angeles

- Race riot

- Billy G. Mills (born 1929), Los Angeles City Councilman, 1963–74, investigated Watts riots

- Charles A. Ott, Jr. (1920–2006), United States Army and California Army National Guard Major General who commanded National Guard soldiers in Los Angeles during the event

- Urban riots

- Watts Prophets

- Wattstax

- Zoot Suit Riots

- Cloward–Piven strategy, derived from the riots in the 1960s

Footnotes

- ↑ "Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles, 1965)". King Encyclopedia. Stanford University. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ↑ The Great Migration: Creating a New Black Identity in Los Angeles. Kcet.org.

- ↑ Theoharis, Jeanne (2006). The Black Power Movement: Rethinking the Civil Rights-Black Power Era. (New York: Routledge), p. 47-49. Archived at Google Books. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Shaw, David (May 25, 2014). "Chief Parker Molded LAPD Image--Then Came the '60s : Police: Press treated officers as heroes until social upheaval prompted skepticism and confrontation.". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ↑ Watts Rebellion (August 1965) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed. The Black Past (August 11, 1965).

- ↑ Dawsey, Darrell (August 19, 1990). "To CHP Officer Who Sparked Riots, It Was Just Another Arrest". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Cohen, Jerry; Murphy, William S. (July 15, 1966). "Burn, Baby, Burn!" Life. Archived at Google Books. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Szymanski, Michael (August 5, 1990). "How Legacy of the Watts Riot Consumed, Ruined Man's Life". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ Dawsey, Darrell (August 19, 1990). "To CHP Officer Who Sparked Riots, It Was Just Another Arrest". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ↑ Woo, Elaine (June 22, 2013). "Rena Price dies at 97; her and son's arrests sparked Watts riots". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Race, Space, and Riots in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ↑ Walker, Yvette (2008). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Alonso, Alex A. (1998). Rebuilding Los Angeles: A Lesson of Community Reconstruction (PDF). Los Angeles: University of Southern California.

- 1 2 3 Barnhill, John H. (2011). "Watts Riots (1965)". In Danver, Steven L. Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History, Volume 3. ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ Woo, Elaine (June 22, 2013). "Rena Price dies at 97; her and son's arrests sparked Watts riots". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- 1 2 "Violence in the City: An End or a Beginning?". Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ↑ "A Report Concerning the California National Guard's Part in Suppressing the Los Angeles Riot, August 1965" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 "The Watts Riots of 1965, in a Los Angeles newspaper... ". Timothy Hughes: Rare & Early Newspapers. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ↑ Reitman, Valerie; Landsberg, Mitchell (August 11, 2005). "Watts Riots, 40 Years Later". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Watts Riot begins - August 11, 1965". This Day in History. History. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Finding aid for the Watts Riots records 0084". Online Archive of California. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ↑ Queally, James (July 29, 2015). "Watts Riots: Traffic stop was the spark that ignited days of destruction in L.A.". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Rustin, Bayard (March 1966). "The Watts". Commentary Magazine. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Oberschall, Anthony (1968). "The Los Angeles Riot of August 1965". Social Problems 15 (3): 322–341. doi:10.2307/799788. JSTOR 799788.

- ↑ Violence in the City—An End or a Beginning?: A Report by the Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, 1965. University of Southern California. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- ↑ Dawsey, Darrell (July 8, 1990). "25 Years After the Watts Riots : McCone Commission's Recommendations Have Gone Unheeded". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- 1 2 Jeffries,Vincent & Ransford, H. Edward. "Interracial Social Contact and Middle-Class White Reaction to the Watts Riot". Social Problems 16.3 (1969): 312–324.

- ↑ Tracy Domingo, Miracle at Malibu Materialized, Graphic, November 14, 2002

- ↑ "Marquette Frye Dead;'Man Who Began Riot". New York Times. December 25, 1986. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ↑ "Rena Price, woman whose arrest sparked Watts riots, dies at 97".

- ↑ Woo, Elaine (June 22, 2013). "Rena Price dies at 97; her and son's arrests sparked Watts riots". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ Abramovich, Alex (July 20, 2001). "The Apes of Wrath – By Alex Abramovich – Slate Magazine". Slate.com. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ↑ Millar, Mark (w), Torres, Wilfredo; Gianfelice, Davide (a). Jupiter's Circle v2, 2 (December 2015), Image Comics

Further reading

- Cohen, Jerry and William S. Murphy, Burn, Baby, Burn! The Los Angeles Race Riot, August 1965, New York: Dutton, 1966.

- Conot, Robert, Rivers of Blood, Years of Darkness, New York: Bantam, 1967.

- Guy Debord, Decline and Fall of the Spectacle-Commodity Economy, 1965. A situationist interpretation of the riots

- Horne, Gerald, Fire This Time: The Watts Uprising and the 1960s, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995.

- Thomas Pynchon, "A Journey into the Mind of Watts", 1966. full text

- David O' Sears, The politics of violence: The new urban Blacks and the Watts riot

- Clayton D. Clingan, Watts Riots

- Paul Bullock, Watts: The Aftermath. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1969.

- Johny Otis, Listen to the Lambs. New York: W.W. Norton and Co. 1968.

External links

- http://www.pbs.org/hueypnewton/times/times_watts.html

- Watts – The Standard Bearer – Watts and the riots of the 1960s.