Waterfall Gully, South Australia

| Waterfall Gully Adelaide, South Australia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

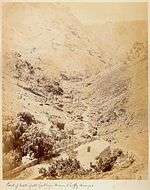

First Falls, Waterfall Gully | |||||||||||||

| Population | 2,522 (2006 census (includes other suburbs))[1] | ||||||||||||

| • Density | 414.8/km2 (1,074.3/sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Established | 1867 | ||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5066 | ||||||||||||

| Area | 6.08 km2 (2.3 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Location | 10 km (6 mi) from Adelaide | ||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Burnside | ||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Bragg | ||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Sturt | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Coordinates: 34°57′36″S 138°40′34″E / 34.960°S 138.676°E

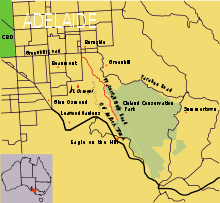

Waterfall Gully is an eastern suburb of the South Australian capital city of Adelaide. It is located in the foothills of the Mount Lofty Ranges around 5 km (3.1 mi) east-south-east of the Adelaide city centre. For the most part, the suburb encompasses one long gully with First Creek at its centre and Waterfall Gully Road running adjacent to the creek. At the southern end of the gully is First Falls, the waterfall for which the suburb was named. Part of the City of Burnside, Waterfall Gully is bounded to the north by the suburb of Burnside, from the north-east to south-east by Cleland Conservation Park (part of the suburb of Greenhill), to the south by Crafers West, and to the west by Leawood Gardens and Mount Osmond.

Historically, Waterfall Gully was first explored by European settlers in the early-to-mid-19th century, and quickly became a popular location for tourists and picnickers. The government chose to retain control over portions of Waterfall Gully until 1884, when they agreed to place the land under the auspices of the City of Burnside. 28 years later the government took back the management of the southern part of Waterfall Gully, designating it as South Australia's first National Pleasure Resort. Today this area remains under State Government control, and in 1972 the Waterfall Gully Reserve, as it was then known, became part of the larger Cleland Conservation Park.

Over the years Waterfall Gully has been extensively logged, and early agricultural interests saw the cultivation of a variety of introduced species as crops, along with the development of local market gardens and nurseries. Attempts to mine the area were largely unsuccessful, but the region housed one of the state's earliest water-powered mills, and a weir erected in the early 1880s provided for part of the City of Burnside's water supply. Today the suburb consists primarily of private residences and parks.

History

The Mount Lofty Ranges, which encompass Waterfall Gully, was first sighted by Matthew Flinders in 1802.[2] The gully itself was discovered soon after the establishment of Adelaide, and Colonel William Light, the first Surveyor General of South Australia, was said to have "decided on the site for Adelaide when viewing the plains from the hills near Waterfall Gully".[2] Nevertheless, the gully had seen human visitors long before the arrival of the Europeans, as the native population had lived in the area for up to 40,000 years prior to Flinders' appearance off the South Australian coast.[3]

Ethnohistory

In Australian Aboriginal mythology, Waterfall Gully and the surrounding Mount Lofty Ranges are part of the story of the ancestor-creator Nganno.[4] Travelling across the land of the native Kaurna people, Nganno was wounded in a battle and laid down to die, forming the Mount Lofty Ranges.[5] The ears of Nganno formed the peaks of Mount Lofty and Mount Bonython, and the region was referred to as Yur-e-billa, or "the place of the ears".[6] The name of the Greater Mount Lofty Parklands, Yurrebilla, was derived from this term,[5] while the nearby town of Uraidla employs a more corrupted form.[2]

Although Hardy states that the Kaurna people did not live in the ranges themselves, they did live on the lower slopes.[7] An early settler of the neighbouring suburb of Beaumont, James Milne Young, described the local Kaurnas: "At every creek and gully you would see their wurlies [simple Aboriginal homes made out of twigs and grass] and their fires at night ... often as many as 500 to 600 would be camped in various places ... some behind the Botanic Gardens on the banks of the river; some toward the Ranges; some on the Waterfall Gully."[8] Their main presence, demarcated by the use of fire against purchasers of land,[6] was on the River Torrens and the creeks that flowed into it, including Waterfall Gully's First Creek.[9]

The land around Waterfall Gully provided the original inhabitants with a number of resources. The bark from the local stringybark trees (Eucalyptus obliqua)[6] was used in the construction of winter huts, and stones and native timbers were used to form tools.[3] Food was also present, and cossid moth larvae along with other species of plants and animals were collected.[6] Nevertheless, there were only a few resources that could only be found on the slopes, and "both hunting and food gathering would in general have been easier on the rich plains".[2]

Early colonial exploration

One of the earliest accounts of Waterfall Gully comes from a "Mr Kent" who, along with Captain Collet Barker and Barker's servant, Miles, climbed Mount Lofty in 1831. In making their ascent the party skirted a ravine—described by Mr Kent as possessing "smooth and grassy sides"—which is believed by Anne Hardy to have been Waterfall Gully.[2] Subsequent to Barker's ascent, the first settlers who were recorded as having climbed Mount Lofty were Bingham Hutchinson and his servant, William Burt. The pair made three attempts to scale the mount before succeeding, and for their first attempt they attempted to traverse Waterfall Gully.[10] The attempt was unsuccessful, but in July 1837, Hutchinson wrote about the gully through which they had travelled. Waterfall Gully he wrote, had proven difficult, as the plants were so thickly grown as to provide a significant barrier to their progress. Near the point of surrender, Hutchinson described how they were "agreeably surprised by seeing a wall of rock about fifty or sixty feet [fifteen to eighteen metres] high, which stretched across the ravine, and from the top of it leapt the brook which had so long been [their] companion".[11] The brook was First Creek, and the waterfall they sighted is today known as First Falls.[12]

Nevertheless, Hutchinson was not the first to see First Falls. The first known recorded sighting of the waterfall by a colonial was that of John William Adams, an emigrant of HMS Buffalo in early January 1837, who named it "Adams' Waterfall". He was traveling with his wife, Susanna and a party consisting of Nicholson's and Breaker's who had the use of a dray to go into the hills. Adams states "we were opposite the spot where the Eagle on the Hill now is, and the question was put, who would volunteer to go down the hillside to try for water".[13]

Development

The area soon became a tourist attraction for the early South Australian colonists, and was a popular destination for picnickers. In 1851 Francis Clark wrote that "Waterfall Gully is the most picturesque place for a picnic that I have ever visited",[14] and by the 1860s the area had become known throughout Adelaide.[12] The use of Waterfall Gully as picnic spot was facilitated by the decision of the government of the day not to subdivide the area containing the waterfalls. Section 920, as it was designated, did not enter into private hands, and thus members of the public were able to access the area from the nearby suburb of Eagle on the Hill on Mount Barker road.[15] The position of the Eagle on the Hill hotel proved advantageous for this, as it permitted visitors to stop by for lunch before walking down the hill in the afternoon.[16]

Other parts of the Waterfall Gully area were subdivided, though, and much of the area was owned by Samuel Davenport. Davenport used the land for timber, grazing, and the cultivation of various crops, including olives and grapes for wine production.[17] Other local residents ran market gardens and nurseries. For example, local residents Wilhelm Mügge and his wife Auguste Schmidt operated "one of the best nurseries and market gardens near Adelaide", and gained a reputation for the cheeses produced from their local dairy farm.[18] Along with farming, the hills and creek were prized areas for the sawyers and splitters,[9] and a number of mines were established in the region from the mid-to-late 19th century. In 1844 the first silver-lead, manganese and iron mines were established in the area, while the 1890s saw a minor gold rush—although "only small quantities were extracted".[19] Of greater success was stone quarrying in Chambers' Gully, which began in 1863 and increased in scale in 1912.[19]

Waterfall Gully was also the site of Burnside's "first secondary industry".[20] In the late 1830s, Thomas Cain built a watermill on First Creek for John Cannan, which was then employed to power a sawmill on Cannan's property. Cannan operated the mill as the "Traversbrook Mill" for approximately two years before selling the venture to a Mr. Finniss. Finniss opted to run the mill as a flour mill instead, and the mill was rebuilt and renamed "Finnissbrook Mill". The mill continued to operate under a variety of owners until the late 1850s, but it was dismantled during the 1880s, and today only traces of the earthworks remain.[21]

During this period the population of the nearby village of Burnside was expanding and required a new water supply. First Creek—which runs down Waterfall Gully and enters the River Torrens near today's Botanic Gardens—was seen as the perfect solution to the water shortage. A weir was built during 1881 and 1882, and was made to hold approximately two megalitres (530,000 US gallons) of water. A pipeline was constructed to the reservoir at Burnside South,[22] and from there the water was used throughout the surrounding area.[23] As a side effect, the weir also reduced the volume of water available to the local market gardeners, and over many years that aspect of the region disappeared.[24]

While the route to the falls from Eagle on the Hill was on public land, the alternative route along the gully was through private properties. Nevertheless, many visitors chose this route, and a combination of public demand and a desire from some of the landowners for improved access to and from their properties—especially from the Mügge family—led to pressure to build a road through the gully. Although there was opposition from some of the locals, the Waterfall Gully road was built in the late 1880s.[25]

The completion of the road led to an increase in visitor numbers.[24] Rather than a bumpy horse ride,[26] visitors could now catch the horse tram to the start of the gully, and walk, cycle or ride to the falls.[27] To provide for tourists, the area gained a number of road-side kiosks and produce stalls, and the Mügge family erected the two story Waterfall Hotel along the path. Furthermore, in 1912 the government opened a kiosk at the base of First Falls,[24] designed in the "style of a Swiss chalet".[28] The hotel is a private residence today, but the kiosk continues to operate.[24]

|

|

| In 1880, Second Falls was covered in lush ferns. Today the ferns have all but disappeared, and introduced species have taken their place. | |

Protection

Although some parts of Waterfall Gully were transferred from the District Council of East Torrens (now the Adelaide Hills Council) to the City of Burnside in 1856 when the suburb's current boundaries were established,[29] the government of the day chose to retain control of a significant portion of Waterfall Gully.[30] Thus it was not until 1884 that the remaining land was transferred to the control of the Burnside Council, eventuating largely through the efforts of Samuel Davenport and G. F. Cleland.[30]

The land remained under the Burnside Council's control until 1912, when the Waterfall Gully Reserve was reclaimed by the government as the first National Pleasure Resort in the state. Initially the reserve was placed under the jurisdiction of the National Parks Advisory Board, but later it was moved to the Tourist Bureau, before finally becoming part of the National Park Commission's portfolio.[31]

In 1945, much of the area that is today's Cleland Conservation Park was purchased by the State Government, largely thanks to the efforts of Professor Sir John Cleland. Most of this land was combined in 1963 to create the park that extends eastwards up the gully to the summit of Mount Lofty and northwards to Greenhill Road. Waterfall Gully Reserve was added to the park in 1972.[28]

Natural disasters

Over the years since European settlement Waterfall Gully has suffered from both bushfires and flooding. The gully was severely hit by a number of bushfires in 1939 that threatened the area, and further bushfires in the early 1940s caused considerable damage because of the war effort diverting supplies and personnel from the Country Fire Service (CFS).[32] Significant floods occurred in 1889 and 1931,[33] and, on the night of 7 November 2005, Waterfall Gully was one of several areas in Adelaide to experience severe flooding. Waterfall Gully was one of the hardest hit suburbs: Bob Stevenson, Duty Officer of the State Emergency Service (SES), commented that "There's an area called Waterfall Gully Road, in the foothills, where one of the creeks comes down, and there's quite a few houses affected there ... there was 40 or so houses affected on that one road alone."[34] Properties were flooded, two bridges nearly collapsed, and 100 m (330 ft) of road was washed away. Burnside council workers, the CFS and the SES repaired the initial damage on the night while reconstruction of infrastructure commenced in late November. Much of the road had been inaccessible, and the suburb was closed except to residents and emergency workers for the remainder of the month.[35]

Geography

Waterfall Gully is situated at an average elevation of 234 m (768 ft) above sea level, in an area of 6.08 km2 (2.35 sq mi). Its most notable geographical features are its gully and waterfall. Langman Reserve, a large local park, is 300 m (980 ft) from the start of Waterfall Gully Road while much of the north-eastern side of the gully is part of Cleland Conservation Park. Adjoining Waterfall Gully, 2 km (1.2 mi) away, is Chambers Gully, which used to function as a land-fill, but has in the past decade been reclaimed as a park through volunteer work.[36] It contains a number of old ruins, walking trails, and springs and is home to a significant number of native species.

Since European Settlement the native plant life has been considerably affected, with the native manna gum and blue gum woodlands being largely cleared for agricultural uses.[37] The large amount of non-native vegetation in the gully is predominantly the result of the early agriculture, although some species were introduced by accident. Introduced species include olive trees, hawthorn, fennel and blackberry.[38] With the reduction of native flora, exotic fauna have flourished around the Waterfall Gully region. These include rabbits, blackbirds and starlings. However, not all of the native wildlife has been lost—bats (in particular, Gould's wattled bat), can be found in the area, as can superb fairy-wrens and Adelaide rosellas, and a large number of unique Australian animals such as kangaroos, koalas and possums can be spotted on some of the walking trails.[39]

Transport

Waterfall Gully is connected to the major Adelaide thoroughfare Greenhill Road by Waterfall Terrace and Glynburn Road, and cars are the preferred mode of transport in the suburb. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics 71.9% of residents in the census area employed private vehicles for their commute to work. Only a small proportion (1.3%) walked to work and but 1.2% cycled, while only 3.6% of Waterfall Gully residents travel to work by bus.[1] The closest bus route for Waterfall Gully is the 142 bus, provided by the multi-service Adelaide Metro.

Waterfall Gully Road is meandering and in some parts quite narrow. This has led to concerns regarding safety, as the road is frequented by both pedestrians and cyclists.[40] After the death of a cyclist in 2007, calls for the repair and resurfacing of the road intensified, with two petitions being tabled in parliament. The accident also led to a safety audit being conducted by TransportSA, and although the results were not released to the public at the time, it called for an investigation of the entire length of the road.[41] As of mid-2008, there has been no clear plan released for the future of the road, with the road missing out on funding in the 2008 state budget.[42]

Residents

In the 2001 Census, the population of the Waterfall Gully census area (which includes the suburbs of Glen Osmond, Leawood Gardens and Mount Osmond) was 2,497 people, in an area of 6.08 square kilometers. Females outnumbered males 54.2% to 45.8%, and some 21.4% of the population was born overseas (see chart for a breakdown). There was only a slight change in the 2006 census, with the population increasing by 25 to 2,522.[1]

The eight strongest religious affiliations in the area (based on the 2006 census figures) were (in descending order): Anglican, Catholic, Uniting, Lutheran, Orthodox Christian, Buddhist, Presbyterian, Church of Christ and Baptist (a combination of other Christian faiths came in somewhere between Presbyterians and the Church of Christ, with 31 adherents). Also of note is the high occurrence of religious affiliation (67.3%) in the region in comparison to the Adelaide (and national) average. Christian belief (64.4%) is most prominent, with little growth in other religions.[1]

Residents in these four suburbs are more affluent than the Adelaide average, with a high occurrence of incomes over A$1000 per week, which is also above the average for the City of Burnside. A majority of workers are employed in professional or white collar fields.[1]

The census area that incorporates Waterfall Gully has a larger proportion of those in both the younger (0–17) and older (60+) age ranges than in the City of Burnside as a whole, and there have been no "numerically significant" changes in the age distribution between the 2001 and 2006 censuses. Similarly, family numbers are also stable, with almost no change between 2001 and 2006.[1]

Attractions

The main attraction of Waterfall Gully is the waterfall, First Falls. It is at the south-eastern end of the road, in land owned by Cleland Conservation Park. The weir at the bottom of the Waterfall was constructed in the late 19th century and was part of Adelaide's early water supply.[23] Development in the area has continued since the construction of a restaurant in 1912.[43] Developments over recent decades have included improving access to the site, upgrading the bridges, and the addition of new signage.[44]

The Waterfall Gully Restaurant was constructed between 1911 and 1912 by South Australian architects Albert Selmar Conrad and his brother Frank,[45] and was formally opened by Sir Day Bosanquet on 9 November 1912.[43] Built in the style of a Swiss chalet, the building has been heritage listed since 1987,[46] and is reputedly haunted by the ghost of a firefighter who died from burns suffered in 1926.[47]

Other fire tracks and walking trails wind around the hills that surround Waterfall Gully, branching off from Chambers Gully, Woolshed Gully or the area around First Creek. Destinations include Crafers, Eagle On The Hill, Mount Lofty, Mount Osmond and the Cleland Wildlife Park, located in the Cleland Conservation Park. The tracks have been completely rebuilt and resurfaced in the past ten years, and a number of older and more perilous routes have been sealed because of the difficult terrain. Many offer views of the city of Adelaide as well as the Gully itself. One of these is notable for connecting to the 1,200 km (750 mi) Heysen Trail, and the trails are highly frequented.

Politics

| 2006 state election[48] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 58.7% | |

| Labor | 25.7% | |

| Greens | 8.2% | |

| Democrats | 4.1% | |

| Family First | 3.3% | |

| 2007 federal election[49] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 61.9% | |

| Labor | 29.2% | |

| Greens | 6.4% | |

| Family First | 1.6% | |

| Democrats | 0.8% | |

Waterfall Gully is part of the state electoral district of Bragg, which has been held since 2002 by Liberal MP Vickie Chapman.[50] In federal politics, the suburb is part of the division of Sturt, and has been represented by Christopher Pyne since 1993.[51] The results shown are from the closest polling station to Waterfall Gully—which is located outside of the suburb—at St David's Church Hall on nearby Glynburn Road (Burnside). Both electorates have traditionally gone to the Liberal Party,[50][51] and Bragg in particular is regarded as a very safe Liberal seat.[50] However, in the 2007 federal election, a strong swing towards the Labor Party and their candidate, Mia Handshin, resulted in the electorate transforming from a "safe [federal] Liberal seat into a marginal one".[52]

In local government, Waterfall Gully is part of the ward of Beaumont within the City of Burnside, and the current Mayor for the district is David Parkin. Beaumont is currently represented by councilors Mark Osterstock and Anne Monceaux.[53]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Glen Osmond — Mount Osmond — Waterfall Gully — Leawood Gardens"

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hardy (1989), p. 5.

- 1 2 Hardy (1989), p. 4.

- ↑ While the Department of Environment and Heritage (2001) refers to Nganno, Hardy (1989, p. 5) employs Yurebilla, and Kleinig names the figure as Jureidla.

- 1 2 Department for Environment and Heritage (2001)

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, Pate & Piddock (2005), p. 3.

- ↑ Hardy (1989), pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Stringer (1986)

- 1 2 Kleinig, "Mt Lofty: A View Down Through the Early Years"

- ↑ Hardy (1989), p. 6.

- ↑ Hutchinson, in Warburton (1981), pp. 187-188. Hutchinson reported that they continued the climb, but surrendered after being faced with another steep ravine separating them from their goal.

- 1 2 Warburton (1977), p. 28.

- ↑ Stringer (1980)

- ↑ Clark, Francis in Warburton (1981), p. 188.

- ↑ Warburton (1981), p. 188.

- ↑ Warburton (1981), p. 102.

- ↑ Warburton (1977), pp. 28–31.

- ↑ Warburton (1981), pp. 188–189.

- 1 2 Warburton (1981), p. 193.

- ↑ Ifould (1956), p. 43.

- ↑ Jones (1981), pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Dridan (1956), p. 87.

- 1 2 Warburton (1981), p. 190.

- 1 2 3 4 Warburton (1981), p. 192.

- ↑ Warburton (1981), pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Warburton (1981), p. 189.

- ↑ Warburton (1981), pp. 191–192.

- 1 2 Hardy (1989), p. 11.

- ↑ Melbourne (1956a), p. 11.

- 1 2 Hardy (1989), p. 7.

- ↑ Hardy (1989), pp. 8–11.

- ↑ Lovett (2005)

- ↑ Warburton (1981), p. 329.

- ↑ "Flash flooding hits Adelaide" (8 November 2005)

- ↑ "Media Release: Hundreds of Homes Affected by Floods"(8 November 2005)

- ↑ "Winning the war on weeds" (10 May 1999), p. 66.

- ↑ "Native Vegetation" (11 November 2007)

- ↑ Hardy (1989), pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Walking Trails (11 November 2007)

- ↑ Garvis (3 October 2007), p. 3.

- ↑ Williams (1 April 2008), p. 16.

- ↑ Charrison (11 June 2008), p. 5.

- 1 2 Melbourne (1956b), p. 156.

- ↑ "Waterfall Gully facelift" (4 June 1998), p. 14.

- ↑ "Place Details: Dr Helen Mayos House, 176–180 Mackinnon Pde, North Adelaide, SA, Australia"

- ↑ "Heritage Places Database Details: Waterfall Gully Kiosk/Restaurant, Cleland Conservation Park"

- ↑ Hardy (1989), p. 12.

- ↑ "State Election 2006 – Polling Booth Results (Burnside, Bragg)" (4 April 2006)

- ↑ "Federal Election 2007 – Polling Booth Results (Burnside, Sturt)" (12 December 2007).

- 1 2 3 Green, Antony (20 April 2006)

- 1 2 Green, Antony (29 December 2007)

- ↑ Vaughan, Joanna (28 December 2007)

- ↑ "The Burnside Council" (26 November 2007)

References

- Charrison, Emily (11 June 2008). "Waterfall Gully Rd misses out on funds". Eastern Courier Messenger. p. 5.

- Department for Environment and Heritage (2001). "The Greater Mount Lofty Parklands – Yurrebilla". Environment South Australia 8 (3). Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- Dridan, J. R. (1956). "Chapter 6: Water supply". In Coleman, Dudley. The First Hundred Years: A History of Burnside in South Australia. Burnside, South Australia: The Corporation of the City of Burnside.

- "Federal Election 2007 – Polling Booth Results (Burnside, Sturt)". Australian Electoral Commission. 12 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Flash flooding hits Adelaide". News.com.au. 8 November 2005. Archived from the original on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- Garvis, Sarah (3 October 2007). "Road rage revival". Eastern Courier Messenger. p. 3.

- "Glen Osmond — Mount Osmond — Waterfall Gully — Leawood Gardens". City of Burnside Community Profile. profile.id. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- Green, Antony (20 April 2006). "2006 South Australian Election. Bragg Electorate Profile". South Australian Election 2006. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- Green, Antony (29 December 2007). "Sturt – Federal Election 2007". Federal Elections 2007. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- Hardy, Ann (1989). The Nature of Cleland. Adelaide: State Publishing. ISBN 0-7243-6542-7.

- "Heritage Places Database Details: Waterfall Gully Kiosk/Restaurant, Cleland Conservation Park". Heritage Places Database. Planning SA. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Ifould, Percy (1956). "Chapter 4: Primary production, mining and other industries". In Coleman, Dudley. The First Hundred Years: A History of Burnside in South Australia. Burnside, South Australia: The Corporation of the City of Burnside.

- Jones, L. J. (1981). "Wind, Water and Muscle-Powered Flour-Mills in Early South Australia". Necomen Society Transactions 53: 97–118.

- Kleinig, Simon. "Mt Lofty: A View Down Through the Early Years" (pdf). The Heysen Trail. The Friends of the Heysen Trail and Other Walking Trails. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- Lovett, Julie (2000). "History of the Burnside CFS". Burnside Country Fire Service. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Media Release: Hundreds of Homes Affected by Floods". SA Country Fire Service. 8 November 2005. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- Melbourne, H. E. S. (1956a). "Chapter 2: Establishment of the Burnside Council and municipal development". In Coleman, Dudley. The First Hundred Years: A History of Burnside in South Australia. Burnside, South Australia: The Corporation of the City of Burnside.

- Melbourne, H. E. S. (1956b). "Chapter 12: Parks, gardens and reserves". In Coleman, Dudley. The First Hundred Years: A History of Burnside in South Australia. Burnside, South Australia: The Corporation of the City of Burnside.

- "Native Vegetation". City of Burnside. 11 November 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Our early beginnings". City of Burnside. 11 November 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Dr Helen Mayos House, 176–180 Mackinnon Pde, North Adelaide, SA, Australia (entry AHD16915)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Smith, Pamela; Pate, F. Donald; Piddock, Susan (2005). The Adelaide Hills Face Zone as a Cultural Landscape (pdf). Understanding Cultural Landscapes – Symposium. Flinders University. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "State Election 2006 – Polling Booth Results (Burnside, Bragg)". State Electoral Commission. 4 April 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- Stringer, Myra (1980). Family history of John William and Susanna Adams. M. Stringer. ISBN 0-9594363-0-8.

- Stringer, Myra (1986). Adams Family History 1774–1986. M. Stringer. ISBN 0-9594363-1-6.

- "The Burnside Council". City of Burnside. 26 November 2007. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- Vaughan, Joanna (28 December 2007). "Federal election results settled". The Advertiser. p. 32.

- "Walking Trails". City of Burnside. 11 November 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- Warburton, Elizabeth (1981). The Paddocks Beneath: A History of Burnside from the Beginning. Burnside, South Australia: The Corporation of the City of Burnside. ISBN 0-9593876-0-9.

- Warburton, J. W. (1977). Five creeks of the River Torrens. Adelaide: Department of adult education, University of Adelaide. ISBN 0-85578-336-2.

- "Waterfall Gully facelift". The Advertiser. 4 June 1998. p. 14.

- Williams, Tim (1 April 2008). "Firstly, fix flooding". Eastern Courier Messenger. p. 16.

- "Winning the war on weeds". Sunday Mail. 10 May 1999. p. 66.

External links

- City of Burnside Community Profile, statistics taken from the ABS

- City of Burnside Electoral Areas

- Cleland National Park

- The Greater Mount Lofty Parklands (Yurrebilla)

- History of the Burnside CFS

- History of the City of Burnside