Oomycete

| Water molds | |

|---|---|

| |

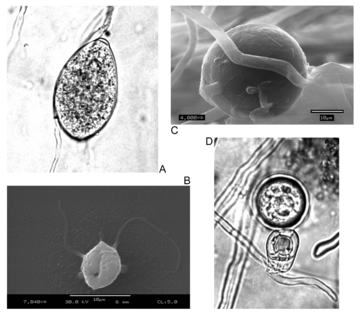

| The reproductive structures of Phytophthora infestans | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukarya |

| (unranked): | SAR |

| Phylum: | Heterokontophyta |

| Class: | Oomycota Arx, 1967[1] |

| Orders and families | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Oomycota or oomycetes (/ˌəʊəˈmaɪsiːt/[4]) form a distinct phylogenetic lineage of fungus-like eukaryotic microorganisms. They are filamentous, microscopic, absorptive organisms that reproduce both sexually and asexually. Oomycetes occupy both saprophytic and pathogenic lifestyles, and include some of the most notorious pathogens of plants, causing devastating diseases such as late blight of potato and sudden oak death. One oomycete, the mycoparasite Pythium oligandrum, is used for biocontrol, attacking plant pathogenic fungi.[5] The oomycetes are also often referred to as water molds (or water moulds), although the water-preferring nature which led to that name is not true of most species, which are terrestrial pathogens. The Oomycota have a very sparse fossil record. A possible oomycete has been described from Cretaceous amber.[6]

Morphology

The oomycetes rarely have septa (see hypha), and if they do, they are scarce,[7] appearing at the bases of sporangia, and sometimes in older parts of the filaments.[8] Some are unicellular, but others are filamentous and branching.[8]

Phylogenetic relationships

This group was originally classified among the fungi (the name "oomycota" means "egg fungus") and later treated as protists, based on general morphology and lifestyle.[6] A cladistic analysis based on modern discoveries about the biology of these organisms supports a relatively close relationship with some photosynthetic organisms, such as brown algae and diatoms. A common taxonomic classification based on these data, places the class Oomycota along with other classes such as Phaeophyceae (brown algae) within the phylum Heterokonta.

This relationship is supported by a number of observed differences in the characteristics of oomycetes and fungi. For instance, the cell walls of oomycetes are composed of cellulose rather than chitin[9] and generally do not have septations. Also, in the vegetative state they have diploid nuclei, whereas fungi have haploid nuclei. Most oomycetes produce self-motile zoospores with two flagella. One flagellum has a "whiplash" morphology, and the other a branched "tinsel" morphology. The "tinsel" flagellum is unique to the Kingdom Heterokonta. Spores of the few fungal groups which retain flagella (such as the Chytridiomycetes) have only one whiplash flagellum.[9] Oomycota and fungi have different metabolic pathways for synthesizing lysine and have a number of enzymes that differ.[9] The ultrastructure is also different, with oomycota having tubular mitochondrial cristae and fungi having flattened cristae.[9]

In spite of this, many species of oomycetes are still described or listed as types of fungi and may sometimes be referred to as pseudofungi, or lower fungi.

Classification

The group is arranged into six orders. Briefly:[8]

- The Lagenidiales are the most primitive; some are filamentous, others unicellular; they are generally parasitic.

- The Leptomitales have wall thickenings that give their continuous cell body the appearance of septation. They bear chitin and often reproduce asexually.

- The Rhipidiales use rhizoids to attach their thallus to the bed of stagnant or polluted water bodies.

- The Saprolegniales are the most widespread. Many break down decaying matter; others are parasites.

- The Peronosporales too are mainly saprophytic or parasitic on plants, and have an aseptate, branching form. Many of the most damaging agricultural parasites belong to this order.

- The Albuginales are considered by some authors to be a family (Albuginaceae) within the Peronosporales, although it has been shown that they are phylogenetically distinct from this order.

(The above after [8]).

Etymology

"Oomycota" means "egg fungi", referring to the large round oogonia, structures containing the female gametes, that are characteristic of the oomycetes.

The name "water mold" refers to their earlier classification as fungi and their preference for conditions of high humidity and running surface water, which is characteristic for the basal taxa of the oomycetes.

Biology

Reproduction

Most of the oomycetes produce two distinct types of spores. The main dispersive spores are asexual, self-motile spores called zoospores, which are capable of chemotaxis (movement toward or away from a chemical signal, such as those released by potential food sources) in surface water (including precipitation on plant surfaces). A few oomycetes produce aerial asexual spores that are distributed by wind. They also produce sexual spores, called oospores, that are translucent, double-walled, spherical structures used to survive adverse environmental conditions.

Pathogenicity

Many oomycetes species are economically important, aggressive plant pathogens. Some species can cause disease in fish. The majority of the plant pathogenic species can be classified into four groups, although more exist.

- The Phytophthora group is a paraphyletic genus that causes diseases such as dieback, late blight in potatoes (the cause of the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s that ravaged Ireland and other parts of Europe),[10] sudden oak death, rhododendron root rot, and ink disease in the European chestnut[11]

- The paraphyletic Pythium group is more prevalent than Phytophthora and individual species have larger host ranges, although usually causing less damage. Pythium damping off is a very common problem in greenhouses, where the organism kills newly emerged seedlings. Mycoparasitic members of this group (e.g. P. oligandrum) parasitize other oomycetes and fungi, and have been employed as biocontrol agents. One Pythium species, Pythium insidiosum, is also known to infect mammals.

- The third group are the downy mildews, which are easily identifiable by the appearance of white, brownish or olive "mildew" on the leaf undersides (although this group can be confused with the unrelated fungal powdery mildews).

- The fourth group are the white blister rusts (Albuginales, which cause white blister disease on a variety of flowering plants. White blister rusts sporulate beneath the epidermis of their hosts, causing spore-filled blisters on stems, leaves and the inflorescence. The Albuginales are currently divided into three genera, Albugo parasitic predominantly to Brassicales, Pustula, parasitic predominantly to Asterales, and Wilsoniana, predominantly parasitic to Caryophyllales. Like the downy mildews, the white blister rusts are obligate biotrophs, which means that they are unable to survive without the presence of a living host.

References

- ↑ Arx, J.A. von. 1967. Pilzkunde. :1-356

- ↑ Winter, G. Rabenhorst’s Kryptogamen-Flora, 2nd ed., vol. 1, part 1, p. 32, 1880 [1879].

- ↑ Dick, M. W. (2001). Straminipilous fungus. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, p. 289.

- ↑ "oomycete". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ Vallance, J.; Le Floch, G.; Deniel, F.; Barbier, G.; Levesque, C. A.; Rey, P. (2009). "Influence of Pythium oligandrum Biocontrol on Fungal and Oomycete Population Dynamics in the Rhizosphere". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75 (14): 4790–800. doi:10.1128/AEM.02643-08. PMC 2708430. PMID 19447961.

- 1 2 "Introduction to the Oomycota". Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- ↑ Kortekamp, A. (2005). "Growth, occurrence and development of septa in Plasmopara viticola and other members of the Peronosporaceae using light- and epifluorescence-microscopy". Mycological Research 109 (Pt 5): 640–648. doi:10.1017/S0953756205002418. PMID 16018320.

- 1 2 3 4 Sumbali, Geeta; Johri, B. M (January 2005). The fungi. ISBN 978-1-84265-153-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Van der Auwera G, De Baere R, Van de Peer Y, De Rijk P, Van den Broeck I, De Wachter R (July 1995). "The phylogeny of the Hyphochytriomycota as deduced from ribosomal RNA sequences of Hyphochytrium catenoides". Mol. Biol. Evol. 12 (4): 671–8. PMID 7659021.

- ↑ Haas, BJ; Kamoun, S; Zody, MC; Jiang, RH; Handsaker, RE; Cano, LM; Grabherr, M; Kodira, CD; et al. (2009). "Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans". Nature 461 (7262): 393–8. doi:10.1038/nature08358. PMID 19741609.

- ↑ Vettraino, A. M.; Morel, O.; Perlerou, C.; Robin, C.; Diamandis, S.; Vannini, A. (2005). "Occurrence and distribution of Phytophthora species in European chestnut stands, and their association with Ink Disease and crown decline". European Journal of Plant Pathology 111 (2): 169–180. doi:10.1007/s10658-004-1882-0.

External links

- Introduction to the Oomycota – University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP)

- DESCRIPTION OF THE PHYLUM OOMYCOTA – Systematic Biology

- Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans

- Oomycetes Genomics Database

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||