Water capacitor

A water capacitor is a device that uses water as its dielectric insulating medium. Conventional capacitors use materials such as glass or ceramic as their insulating medium to store an electric charge. Water capacitors were created mainly as a novelty item or for laboratory experimentation, and can be made with simple materials. Water exhibits the quality of being self-healing; if there is a breakdown in the water, it quickly returns to its original and undamaged state. Other liquid insulators are prone to carbonization after breakdown and tend to lose their hold off strength over time. The drawback to using water is the short length of time it can hold off the voltage, typically in the microsecond to ten microsecond (us) range. Deionized water is relatively inexpensive and is environmentally safe. These characteristics along with the high dielectric constant make water an excellent choice for building large capacitors. If a way can be found to reliably increase the hold off time for a given field strength, then there will be more applications for water capacitors.[1]

Water has been shown not to be a very reliable substance to store electric charge long term, so more reliable materials are used for capacitors in industrial applications.[2] However water has the advantage of being self healing after a breakdown, and if the water is steadily circulated through a de-ionizing resin and filters, then the loss resistance and dielectric behavior can be stabilized. Then in certain unusual situations such as the generation of extremely high voltage but very short, pulses a water capacitor may be a practical solution — such as in an experimental Xray pusler[3]

History

Capacitors can originally be traced back to a device called a Leyden jar, created by the Dutch physicist Pieter van Musschenbroek.[4] The Leyden jar consisted of a glass jar with tin foil layers on the inside and outside of the jar. A rod electrode was directly connected to the inlayer of foil by means of a small chain or wire. This device stored static electricity created when amber and wool where rubbed together.[5]

Although the design and materials used in capacitors have changed greatly throughout history, the basic fundamentals remain the same. In general, capacitors are very simple electrical devices which can have many uses in today's technologically advanced world. A modern capacitor usually consists of two conducting plates sandwiched around an insulator. Electrical researcher Nicola Tesla described capacitors as the "electrical equivalent of dynamite".[6]

Theory of operation

A capacitor is a device in which electrical energy is introduced and can be stored for a later time. A capacitor consists of two conductors separated by a non-conductive region. The non-conductive region is called the dielectric or electrical insulator. Examples of traditional dielectric media are air, paper, and certain semiconductors. A capacitor is a self-contained system, is isolated with no net electric charge. The conductors must hold equal and opposite charges on their facing surfaces.[7]

Applications

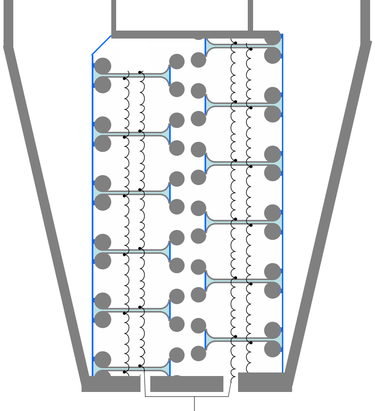

A simple type of water capacitor is created by using water filled glass jars and some form of insulating material to cover the ends of the jar. Water capacitors are not widely used in the industrial community due to their large size for a given capacitance. The conductivity of water can change very quickly and is unpredictable if left open to atmosphere. Many variables such as temperature as well as pH levels and salinity have been shown to alter conductivity in water. As a result, there are better alternatives to the water capacitor in the majority of applications.

The pulse withstand voltage of carefully purified water can be very high - over 100kV/cm (comparing to about 100mm for the same voltage in dry air) [8]

A capacitor is designed to store electric energy when disconnected from its charging source. Compered to more conventional devices, water capacitors are currently not practical devices for industrial applications. Capacitance can be increased by the addition of electrolytes and minerals to the water, but this increases the self leakage, and cannot be done beyond its saturation point.[9]

Hazards and Benefits

Modern high voltage capacitors may retain their charge long after power is removed. This charge can cause dangerous, or even potentially fatal, shocks if the energy is more than a few joules. At much lower levels stored energy can still cause damage to connected equipment. Water capacitors, being self discharging, (for totally pure water, only thermally ionized, at 25C the ratio of conductivity to permittivity means self discharge is circa 180us, faster with higher temperatures or dissolved impurities) usually cannot be made store enough residual electrical energy to cause serious bodily injury. Unlike many large industrial high voltage capacitors, water capacitors do not require oil. Oil found in many older designs of capacitors can be toxic to both animals and humans. If a capacitor breaks open and its oil is released, the oil often finds its way into the water table which can cause health problems over time.[10]

Notes

- ↑ Kristiansen, Magne. "DSWA-TR-97-30" (PDF). Defense Special Weapons Agency.

- ↑ Egal,Hammer, Geoff, Spinner. "Water and Glass Capacitor". Reseah in Utilization of Free Energy Found in Nature. Geoff Egal. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Horioka, Kazuhiko (Mar 2007). "Pumping system for Capillary Dscharge Laser" (PDF). National institute for Fusion Science.

- ↑ Bolund, Björn F; Berglund, M; Bernhoff, H. (March 2003). "Dielectric study of water/methanol mixtures for use in pulsed-power water capacitors". Journal of Applied Physics 93 (3): 1–6. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ Korotkov, S; Aristov, Y; Kozlov, A; Korotkov, D; Rol'nik, I (March 2011). "A generator of electrical discharges in water.". Instruments & Experimental Techniques 54 (2): 190–193. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Schulz, Alexander (2011). Capacitors : Theory, Types, And Applications. Ipswich, MA: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN eBook.

- ↑ Shectman, Jonathan (2003), Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 18th Century, Greenwood Press, pp. 87–91, ISBN 0-313-32015-2 Sewell, Tyson (1902), The Elements of Electrical Engineering, Lockwood, p. 18

- ↑ Schulz, Alexander (2011). Capacitors : Theory, Types, And Applications. Ipswich, MA: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN eBook.

- ↑ "Dielectric-breakdown tests of water at 6MV" (PDF). Sandia Labs.

- ↑ Dorf, Richard C.; Svoboda, James A. (2001). Introduction to Electric Circuits (5th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-38689-6.

- ↑ Moller, Peter; Kramer, Bernd (December 1991), "Review: Electric Fish", BioScience (American Institute of Biological Sciences) 41 (11): 794–6 [794], doi:10.2307/1311732, JSTOR 1311732

References

- Egal,Hammer, Geoff, Spinner. "Water and Glass Capacitor". Reseah in Utilization of Free Energy Found in Nature. Geoff Egal. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Bolund, Björn F.; Berglund, M.; Bernhoff, H. (March 2003). "Dielectric study of water/methanol mixtures for use in pulsed-power water capacitors". Journal of Applied Physics 93 (3): 1–6. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Korotkov, S; Aristov, Y; Kozlov, A; Korotkov, D; Rol'nik, I (March 2011). "A generator of electrical discharges in water.". Instruments & Experimental Techniques 54 (2): 190–193. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Schulz, Alexander (2011). Capacitors : Theory, Types, And Applications. Ipswich, MA: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN eBook.

- Dorf, Richard C.; Svoboda, James A. (2001). Introduction to Electric Circuits (5th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-38689-6.

- "The First Condenser — A Beer Glass". SparkMuseum.

- Roger S. Amos, Geoffrey William Arnold Dummer (1999). Newnes Dictionary of Electronic (4th ed.). Newnes. p. 83. ISBN 0-7506-4331-5.

- Fink, Donald G.; H. Wayne Beaty (1978). Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers, Eleventh Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-020974-X.

- Bellis, Mary. "History of the Electric Battery". About.com.

- Moller, Peter; Kramer, Bernd (December 1991), "Review: Electric Fish", BioScience (American Institute of Biological Sciences) 41 (11): 794–6 [794], doi:10.2307/1311732, JSTOR 1311732

- Shectman, Jonathan (2003), Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 18th Century, Greenwood Press, pp. 87–91, ISBN 0-313-32015-2

Sewell, Tyson (1902), The Elements of Electrical Engineering, Lockwood, p. 18.