Abu Sayyaf

| Abu Sayyaf | |

|---|---|

|

Participant in the Moro conflict in the Philippines, the Moro attacks on Malaysia, Military intervention against ISIL, and the Global War on Terrorism | |

|

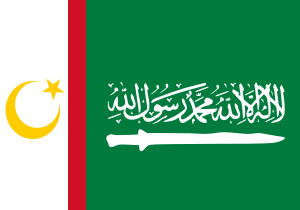

The Black Standard of ISIL, which was adopted by Abu Sayyaf | |

| Active | 1991–present |

| Ideology |

Islamism Islamic fundamentalism Salafi[1] |

| Leaders |

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (Leader of ISIL) Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani †[2] Khadaffy Janjalani †[3] Radullan Sahiron[4][5] Isnilon Totoni Hapilon[6][7] Mahmur Japuri †[8] |

| Headquarters | Jolo, Sulu, Philippines |

| Area of operations | Philippines, Malaysia |

| Strength | 300+[9] |

| Part of |

|

| Allies |

14K Triad[10] |

| Opponents |

|

Abu Sayyaf (![]() i/ˌɑːbuː/ /sɑːˌjɔːf/; Arabic: جماعة أبو سياف; Jamāʿah Abū Sayyāf, ASG, Filipino: Grupong Abu Sayyaf)[15] is a militant Islamist group based in and around Jolo and Basilan islands in the southwestern part of the Philippines, where for more than four decades, Moro groups have been engaged in an insurgency for an independent province in the country. The group is considered very violent,[16] and was responsible for the Philippines' worst terrorist attack, the bombing of Superferry 14 in 2004, which killed 116 people.[17]

The name of the group is derived from the Arabic ابو, abu ("father of") and sayyaf ("swordsmith").[18] As of 2012, the group was estimated to have between 200 and 400 members,[19] down from 1250 in 2000.[20] They use mostly improvised explosive devices, mortars, and automatic rifles.

i/ˌɑːbuː/ /sɑːˌjɔːf/; Arabic: جماعة أبو سياف; Jamāʿah Abū Sayyāf, ASG, Filipino: Grupong Abu Sayyaf)[15] is a militant Islamist group based in and around Jolo and Basilan islands in the southwestern part of the Philippines, where for more than four decades, Moro groups have been engaged in an insurgency for an independent province in the country. The group is considered very violent,[16] and was responsible for the Philippines' worst terrorist attack, the bombing of Superferry 14 in 2004, which killed 116 people.[17]

The name of the group is derived from the Arabic ابو, abu ("father of") and sayyaf ("swordsmith").[18] As of 2012, the group was estimated to have between 200 and 400 members,[19] down from 1250 in 2000.[20] They use mostly improvised explosive devices, mortars, and automatic rifles.

Since its inception in 1991, the group has carried out bombings, kidnappings, assassinations, and extortion[21] in what they describe as their fight for an independent Islamic province in the Philippines.[22] They have also been involved in criminal activities, including kidnapping, rape, child sexual assault, drive-by shootings, extortion, and drug trafficking,[23] and the goals of the group "appear to have alternated over time between criminal objectives and a more ideological intent".[19]

The group has been designated as a terrorist group by the United Nations, Australia, Canada, the UAE, the United Kingdom and the United States.[22] In 2002, fighting Abu Sayyaf became a mission of the American military's Operation Enduring Freedom and part of the Global War on Terrorism.[24][25] Several hundred United States soldiers are also stationed in the area to mainly train local forces in counter terror and counter guerrilla operations, but as a status of forces agreement and under Philippine law are not allowed to engage in direct combat.[25]

The group was founded by Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani, and led after his death in 1998 by his younger brother Khadaffy Janjalani who was killed in 2007. On July 23, 2014, Abu Sayyaf leader Isnilon Totoni Hapilon swore an oath of loyalty to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIL.[6] In September 2014, the group began kidnapping people to ransom, in the name of ISIL.[26]

History

In the early 1970s, the Moro National Liberation Front (M.N.L.F.) was the main Muslim rebel groups fighting in Basilan and Mindanao in the southern Philippines.[22]

Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani, the older brother of Khadaffy Janjalani, had been a teacher from Basilan, who later studied Islamic theology and Arabic in Libya, Syria and Saudi Arabia during the 1980s.[27][28] Abdurajik then went to Afghanistan to fight against the Soviet Union and the Afghan government during the Soviet war in Afghanistan in the 1980s. During that period, he is alleged to have met Osama Bin Laden and been given $6 million to establish a more Islamic group with the M.N.L.F. in the southern Philippines, made up of members of the extant M.N.L.F.[29] By then, as a political solution in the southern Philippines, ARMM had been established in 1989.

Both Abdurajik Abubakar and his younger brother who succeeded him were natives of Isabela City, currently one of the poorest cities of the Philippines. Located on the North-Western part of the island of Basilan, Isabela is also the capital of Basilan province, across the Isabela Channel from the Malamwi Island. But Isabela City is administered under the Zamboanga Peninsula political region north of the island of Basilan, while the rest of the island province of Basilan is now (since 1996) governed as part of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) to the east.

Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani leadership (1989–1998)

M.N.L.F. had moderated into an established political government, the ARMM. It was established in 1989, fully institutionalized by 1996 and which eventually became the ruling government in southern Mindanao.

When Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani returned home to Basilan island in 1990, he gathered radical members of the old M.N.L.F. who wanted to resume armed struggle for an independent Islamic state and in 1991 established the Abu Sayyaf.[22]

Janjalani was provided some funding by a Saudi Islamist, Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, who came to the Philippines in 1987 or 1988 and was head of the Philippine branch of the International Islamic Relief Organization foundation. A defector from Abu Sayyaf told Filipino authorities, "The IIRO was behind the construction of Mosques, school buildings and other livelihood projects" but only "in areas penetrated, highly influenced and controlled by the Abu Sayyaf." According to the defector "Only 10 to 30% of the foreign funding goes to the legitimate relief and livelihood projects and the rest go to terrorist operations."[30][31][32][33] Khalifa had married a local woman, Alice "Jameelah" Yabo,[34]

By 1995 Abu Sayyaf was active in large scale bombings and attacks in the Philippines. The Abu Sayyaf's first attack was the assault on the town of Ipil in Mindanao in April 1995. This year also marked the escape of 20-year-old Khadaffy Janjalani from Camp Crame in Manila along with another member named Jovenal Bruno.

On December 18, 1998, Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani was killed in a gun battle with the Philippine National Police on Basilan Island.[35] He is thought to have been about age 39 at the time of his death.[28] The death of Aburajik Abubakar Janjalani marked a turning point in Abu Sayyaf operations, shifting from its ideological focus to more general kidnappings, murders and robberies, as the younger brother Khadaffy Janjalani succeeded Abdurajak.

Consequently, being on the social or political division line, Basilan, Jolo and Sulu have seen some of the fiercest fighting between government troops and the Muslim separatist group Abu Sayyaf through the early 1990s. The Abu Sayyaf primarily operates in the southern Philippines with members traveling to Manila and other provinces in the country. It was reported that Abu Sayyaf had begun expanding into neighbouring Malaysia and Indonesia by the early 1990s.

The Abu Sayyaf is one of the smallest, but strongest of the Islamist separatist groups in the Philippines. Some Abu Sayyaf members have studied or worked in Saudi Arabia and developed ties to mujahadeen while fighting and training in the war against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.[27] Abu Sayyaf proclaimed themselves as mujahideen and freedom fighters but are not supported by many people in the Philippines including its Muslim clerics.

Khadaffy Janjalani leadership (1999–2007)

Until his death in a gunbattle on September 4, 2006, Khaddafy Janjalani was considered the nominal leader of the group by the Armed Forces of the Philippines. The 23-year-old Khadaffy Janjalani then took leadership of one of Abu Sayyaf's factions in an internecine struggle.[35][36] He then worked to consolidate his leadership of the Abu Sayyaf, causing the group to appear inactive for a period. After Janjalani's leadership was secured, the Abu Sayyaf began a new strategy, as they proceeded to take hostages.

The group's motive for kidnapping became more financial than religious during the period of Khadaffy's leadership, according to locals in the areas associated with Abu Sayyaf. The hostage money is probably the method of financing of the group.[29] The group expanded its operations to Malaysia in 2000 when it abducted foreigners from two resorts. This action was condemned by most leaders in the Islamic world.

It was also responsible for the kidnapping and murder of more than 30 foreigners and Christian clerics and workers, including Martin and Gracia Burnham.[37][38]

A commander named Abu Sabaya was killed in 2002 while trying to evade forces.[39]

Galib Andang, one of the leaders of the group, was captured in Sulu in December 2003.[35][37][40][41]

An explosion at a military base in Jolo on February 18, 2006 was blamed on Abu Sayyaf by Brig. General Alexander Aleo, an Army officer.[42]

Khadaffy Janjalani was indicted in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia for his alleged involvement in terrorist attacks, including hostage taking by Abu Sayyaf and murder, against United States nationals and other foreign nationals in and around the Republic of the Philippines.[43]

Consequently, on February 24, 2006, Janjalani was among six fugitives in the second and most recent group of indicted fugitives to be added to the FBI Most Wanted Terrorists list along with two fellow members of the Abu Sayyaf, including Isnilon Totoni Hapilon and Jainal Antel Sali, Jr.[44][45]

On December 13, 2006, it was reported that Abu Sayyaf members may have been planning attacks during the ASEAN summit in the Philippines. The group was reported to have been training alongside Jemaah Islamiyah militants. The plot was reported to have involved detonating a car bomb in Cebu City where the summit was scheduled to take place.[46]

On December 27, 2006, the Philippine military reported that Janjalani's remains had been recovered near Patikul, in Jolo in the southern Philippines and that DNA tests had been ordered to confirm the discovery. He was allegedly shot in the neck in an encounter with government troops on September on Luba Hills, Patikul town in Sulu.

Present time (2010-2014)

In a video published in the summer of 2014, senior Abu Sayyaf leader Isnilon Hapilon and other masked men swear their allegiance or “bay'ah” to the "Islamic State" (ISIS) caliph. “We pledge to obey him on anything which our hearts desire or not and to value him more than anyone else. We will not take any emir (leader) other than him unless we see in him any obvious act of disbelief that could be questioned by Allah in the hereafter.”[47] For many years prior to this Islamic State's competitor, Al Qaeda, had the support of Abu Sayyaf "through various connections." [47] Observers were skeptical of whether the pledge would lead to Abu Sayyaf becoming an ISIS outpost in Southeast Asia, or was simply a way for the group to taking advantage of the international publicity Islamic State is getting.[47]

Motivation, beliefs, targets

Filipino Islamist guerillas such as Abu Sayyaf, have been described as “rooted in a distinct class made up of closely knit networks built through marriage of important families through socioeconomic backgrounds and family structures," according to Michael Buehler, a lecturer in comparative politics at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. This tight-knit, familial structure provides resilience but also limits their ability to expand.[47] The commander of the Philippines military’s Western Mindanao Command Lieutenant General Rustico Guerrero, also describes Abu Sayyaf as "a local group with a local agenda."[47]

Two kidnapping victims, (Martin and Gracia Burnham) who were kept in captivity by ASG for over a year, "gently engaged their captors in theological discussion" and found Abu Sayyaf fighters to be unfamiliar with the Qur'an. They had only "a sketchy" notion of Islam, which they saw as "a set of behavioral rules, to be violated when it suited them", according to author Mark Bowden. As "holy warriors, they were justified in kidnapping, killing and stealing. Having sex with women captives was justified by their claiming them as "wives".[48]

Unlike the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and Moro National Liberation Front, the group is not recognized by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, and according to author Dr Robert (Bob) East, was seen as "nothing more than a criminal operation" at least prior to 2001.[49]

A Center for Strategic and International Studies report by Jack Fellman notes the political rather than religious motivation of ASG. He quotes ASG leader Khadaffy Janjalain's statement that his brother (the former leader of ASG) was right to split from the more moderate NMLF because "up to now, nothing came out" of attempts to gain more autonomy for Moro Muslims. This suggests, Fellman believes, that ASG "is merely the latest, albeit most violent, iteration of Moro political dissatisfaction that has existed for the last several decades."[50]

Targets

Most of the Abu Sayyaf victims have been Filipinos. However, Australian, British, Canadian, Chinese, French, German and Malaysian tourists, businessmen and police have been targeted. Westerners, especially Americans, have been targeted for political and racial reasons. A spokesman for the Abu Sayyaf has stated that, "We have been trying hard to get an American because they may think we are afraid of them". He added, "We want to fight the American people".[51] In 1993, Abu Sayyaf kidnapped an American Bible translator in the southern Philippines. In 2000, Abu Sayyaf captured an American Muslim visiting Jolo and demanded that the United States release Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman and Ramzi Yousef, who were jailed for their involvement in the World Trade Center bombing of 1993.

A Japanese businessman was killed when a Cebu to Tokyo Philippine Airlines flight was bombed on December 10, 1994 by Abu Sayyaf.[52] While the body of Korean hostage Nwi Seong Hong, who had been held by Abu Sayyaf, was found in 2012.[53][54][55]

Crimes

Kidnappings

In the Philippines

Jeffrey Schilling

Jeffrey Schilling, an American citizen and Muslim convert, was held by Abu Sayyaf for 8 months after being captured while visiting a terrorist camp with his wife, Ivy Osani. Abu Sayyaf demanded a $10 million ransom for his release, but Schilling escaped after more than 7 months and was picked up by the Philippine Marine Corps on April 12, 2001.[56][57]

Many commentators have been critical of Schilling, who had reportedly walked into the camp. Schilling claims to have been invited by his wife's distant cousin who was a member of Abu Sayyaf.[58]

Martin and Gracia Burnham

On May 27, 2001, an Abu Sayyaf raid kidnapped about 20 people from Dos Palmas, an expensive resort in Honda Bay, to the north of Puerto Princesa City on the island of Palawan, which had been "considered completely safe". The most "valuable" of the hostages were three North Americans, Martin and Gracia Burnham, a missionary couple, and Guillermo Sobero, a Peruvian-American tourist who was later beheaded by Abu Sayyaf, for whom Abu Sayyaf demanded $1 million in ransom.[59] The hostages and hostage-takers then returned hundreds of kilometres back across the Sulu Sea to the Abu Sayyaf's territories in Mindanao.[60]

According to author Mark Bowden, the leader of the raid was Abu Sabaya. According to Gracia Burnham, she told her husband "to identify his kidnappers" to authorities "as 'the Osama bin Laden Group,' but Burnham was unfamiliar with that name and stuck with" Abu Sayyaf. After returning to Mindanao, Abu Sayyaf operatives conducted numerous raids, "including one at a coconut plantation called Golden Harvest; they took about 15 people captive there and later used bolo knives to hack the heads off two men. The number of hostages waxed and waned as some were ransomed and released, new ones were taken and others were killed."[60]

On June 7, 2002, about a year after the raid, Philippine army troops conducted a rescue operation in which two of the three hostages held, Martin Burnham and Filipino nurse, Ediborah Yap, were killed. The remaining hostage was wounded and the hostage takers escaped.

In July 2004, Gracia Burnham testified at a trial of eight Abu Sayyaf members and identified six of the suspects as being her erstwhile captors, including Alhamzer Limbong, Abdul Azan Diamla, Abu Khari Moctar, Bas Ishmael, Alzen Jandul, and Dazid Baize.

"The eight suspects sat silently during her three-hour testimony, separated from her by a wooden grill. They face the death sentence if found guilty of kidnapping for ransom. The trial began this year and is not expected to end for several months."[61]

Alhamzer Limbong was later killed in a prison uprising.[62]

Gracia Burnham has claimed that Philippine military officials were colluding with her captors, saying that the Armed Forces of the Philippines "didn't pursue us...As time went on, we noticed that they never pursued us".[63]

Journalists abducted since 2000

ABS-CBN's Newsbreak reported that Abu Sayyaf abducted at least 20 journalists since 2000 (mostly foreign journalists) and all of them were eventually released upon payment of ransom.

Ces Drilon and cameramen Jimmy Encarnacion and Angelo Valderama were the latest of its kidnap victims. The journalists held captive were

- GMA-7 television reporter Susan Enriquez (April 2000, Basilan, a few days);

- 10 Foreign journalists (7 German, 1 French, 1 Australian and 1 Danish, on May 2000, Jolo, for 10 hours);

- German Andreas Lorenz of the magazine Der Spiegel (July 2000, Jolo, for 25 days; he was also kidnapped in May);

- French television reporter Maryse Burgot and cameraman Jean-Jacques Le Garrec and sound technician Roland Madura (July 2000, Jolo, for 2 months);

- ABS-CBN television reporter Maan Macapagal and cameraman Val Cuenca (July 2000, Jolo, for 4 days);

- Philippine Daily Inquirer contributor and Net 25 television reporter Arlyn de la Cruz (January 2002, Zamboanga, for 3 months)

- GMA-7 television reporter Carlo Lorenzo and cameraman Gilbert Ordiales (September 2002, Jolo, for 6 days).[64]

2009 Red Cross kidnapping

On January 15, 2009, Abu Sayyaf kidnapped International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) delegates in Patikul, Sulu province, Philippines. The three ICRC workers had finished conducting field work in Sulu province, located in the southwest of the country, when they were abducted by an unknown group, later confirmed as Abu Sayyaf leader Albader Parad's group. Parad himself was said to be involved in the kidnapping.[65] All three workers were eventually released. According to a CNN story, Parad was reportedly killed, along with five other militants, in an assault raid by Philippine marines in Sulu province on Sunday, February 21, 2010.

Warren Rodwell

Warren Richard Rodwell (born June 16, 1958[66] Homebush NSW)[67] a former soldier[68] in the Australian Army, and university English teacher,[69] grew up in Tamworth NSW[70] He was shot through the right hand when seized[71] from his home at Ipil, Zamboanga Sibugay on the island of Mindanao in the southern Philippines on December 5, 2011[72] by Abu Sayyaf (ASG) militants.[73] Rodwell later had to have a finger amputated.[74]

The ASG threatened to behead Rodwell[75] if the original ransom demand for $US2 million was not paid.[76] Both the Philippine and Australian governments had strict policies of refusing to pay ransoms.[77] Australia formed a multi-agency task force to assist the Philippine authorities, and liaise with Rodwell's family.[78] A news blackout was imposed.[79] Filipino politicians helped negotiate the release.[80] After the payment of $AUD94,000[81] for "board and lodging" expenses[82] by his siblings, Rodwell was released 472 days later on March 23, 2013.[83] The incumbent Australian prime minister praised the Philippines government for securing Rodwell's release. Tribute was also made to Australian officials from the Department of Foreign Affairs, the Australian Federal Police and Defence.[84] Rodwell subsequently returned to Australia.[85]

As part of the 2015 Australia Day Honours, Australian Army Lieutenant Colonel Paul Joseph Barta was awarded the Conspicuous Service Cross (CSC) for outstanding devotion to duty as the Assistant Defence Attaché Manila during the Australian whole of government response to the Rodwell kidnap for ransom (and immediately following, the devastation of Typhoon Haiyan). At the 2015 Australian Federal Police Foundation Day award ceremony in Canberra, fourteen AFP members received the Commissioners’ Group Citation for Conspicuous Conduct for their work in support of the Philippine National Police and Australian Government efforts to release Australian man Warren Rodwell.[86]

By the end of his 15 months as a hostage in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, Rodwell had lost about 30 kilograms in weight due to starvation,[87] His biography 472 Days Captive of the Abu Sayyaf - The Survival of Australian Warren Rodwell by independent researcher Dr Robert (Bob) East was published by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, United Kingdom (2015) ISBN 1-4438-7058-7[88] In popular culture, Blue Mountains (Sydney) techno Cowpunk band Mad Cowboy Disease composed, performed and released Situation Not Normal, a song written by Rodwell, based on his ordeal.[89]

Award-winning Filipino journalist and CEO of Rappler,[90] Maria A. Ressa wrote at some length about the Warren Rodwell case in the 2013 international edition of her Imperial College Press - published book From Bin Laden to Facebook: 10 Days of Abduction, 10 Years of Terrorism ISBN 978-1-908979-53-7 [91] (Refer to Pages 265 - 271) Crowdsourcing for ransom, and social media (such as, Facebook and YouTube) were used by Abu Sayyaf during negotiations. The author asserts on Page 270; "Social media is changing what was once a closed dialogue between kidnappers, their victims and governments."

Also, Colonel (reserve) in the Israel Defence Forces and research fellow at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT), Dr Shaul Shay, analysed the Warren Rodwell terror abduction in: Global Jihad and The Tactic of Terror Abduction : A Comprehensive Review of Islamic Terrorist Organisations. ISBN 978-1-84519-611-0 (Refer to Chapter 10) (Sussex Academic Press). [92]

In January 2015, Mindanao Examiner newspaper reported the arrest of Barahama Ali[93] kidnap gang sub-leaders linked to the kidnapping of Warren Rodwell, who was seized by at least 5 gunmen (disguised as policemen), and eventually handed over or sold by the kidnappers to the Abu Sayyaf in Basilan province.[94]

In May 2015, ex-Philippine National Police (PNP) officer Jun A. Malban was arrested in Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia for the crime of "Kidnapping for Ransom" after Rodwell identified him as the negotiator/spokesperson of the Abu Sayyaf Group during his captivity. Further PNP investigation revealed that Malban is the cousin of Abu Sayyaf leaders Khair Mundos and his brother Borhan Mundos. (Both were arrested in 2014).[95] The director of the Anti-Kidnapping Group (AKG) stated that Malban's arrest resulted from close coordination by the PNP, National Bureau of Investigation (Philippines) and Presidential Anti-Organized Crime Commission with the Malaysian counterparts and through Interpol.[96]

In August 2015, Edeliza Sumbahon Ulep,[97] alias Gina Perez, was arrested at Trento, Agusan del Sur during a joint manhunt operation by police and military units. Ulep was tagged as the ransom courier of the Abu Sayyaf bandits in Zamboanga Sibugay in the kidnapping of Rodwell.[98]

In Malaysia

2000 Sipadan kidnappings

On May 3, 2000, Abu Sayyaf guerillas occupied the Malaysian dive resort island Sipadan and took 21 hostages, including 10 tourists and 11 resort workers – 19 non-Filipino nationals in total. The hostages were taken to an Abu Sayyaf base in Jolo, Sulu.[99]

Two Muslim Malaysians were released soon after, however Abu Sayyaf made various demands for the release of several prisoners, including 1993 World Trade Center bomber Ramzi Yousef and $2.4 million. In July, a Filipino television evangelist and 12 of his crew offered their help and went as mediators for the relief of other hostages.[100] They, three French television crew members and a German journalist, all visiting Abu Sayyaf on Jolo, were also taken hostage.[101] Most hostages were released in August and September 2000, partly due to mediation by Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi and an offer of $25 million in "development aid".[102]

Abu Sayyaf conducted a second raid on the island of Pandanan near Sipadan on September 10 and seized three more Malaysians.[103] The Philippine army launched a major offensive on September 16, 2000, rescuing all remaining hostages, except Filipino dive instructor Roland Ullah. He was eventually freed in 2003.[99]

Abu Sayyaf coordinated with the Chinese 14K Triad gang in carrying out the kidnappings.[104] The 14K Triad has militarily supported Abu Sayyaf.[10]

2013 Pom Pom kidnappings

On November 15, 2013, Abu Sayyaf militants raided a resort on a Malaysian island of Pom Pom in Semporna, Sabah.[105][106] During the ambush, Taiwanese citizen Chang An-wei was kidnapped and her husband, Hsu Li-min, was killed.[107] Chang was taken to the Sulu Archipelago in the southern Philippines.[105] Gene Yu, an American and former US Army Special Forces captain was instrumental in negotiating, locating and working to free Taiwanese citizen Chang An-wei from Abu Sayyaf militants with Filipino special forces and private security contractors in 2013. Chang was freed in Sulu Province and returned to Taiwan on December 21.[108][109][110]

2014 Singamata resort, Baik Island and Kampung Air Sapang fish farm kidnappings

On April 2, 2014, a group believed to originate from Abu Sayyaf militants raided a resort off Semporna, Sabah.[111][112] During the raid, Gao Huayun, a Chinese tourist from Shanghai and Marcy Dayawan, a Filipino resort worker who was on the resort were kidnapped and taken to the Sulu Archipelago.[111][113] The two hostages were later rescued after a collaboration between the Malaysian and the Philippines security forces.[114][115]

On May 6, 2014, a group comprising five Abu Sayyaf gunmen raided a Malaysian fish farm in Baik Island, Sabah and kidnapped the fish farm manager, after which the hostage was brought to Jolo island.[116][117] He was later freed on July with the help of Malaysian negotiators.[118]

On June 16, 2014, two gunmen believed to be from the Abu Sayyaf group kidnapped another Chinese fish farm manager and one Filipino in Kampung Air Sapang, Kunak, Sabah.[119][120] One of the kidnap victims, a Filipino fish farm worker, managed to escape and went missing.[121][122] Meanwhile, the fish farm manager was taken to Jolo.[123] He was later released on December 10.[124]

The Malaysian authorities have identified five Filipinos, the "Muktadir brothers", as behind all of the kidnapping cases. They then sell their hostages to the Abu Sayyaf group.[125]

2015 Ocean Seafood Restaurant kidnappings

On May 15, 2015, four armed men from the Abu Sayyaf-based group abducted two people in a resort in Sandakan, Sabah and brought them to Parang, Sulu.[126][127] One of the hostage was released on November 9, after six months in captivity,[128] while another one, Bernard Then, was beheaded due to ransom demands not being met.[129][130]

Superferry 14 Bombing

Superferry 14 was a large ferry destroyed by a bomb on February 27, 2004, killing 116 people in the Philippines' worst terrorist attack and the world's deadliest terrorist attack at sea.[17]

On that day, the 10,192 ton ferry sailed out of Manila with about 900 passengers and crew on board. A television set filled with 8 lb. (4 kilograms) of TNT had been placed on board. 90 minutes out of port, the bomb exploded. 63 people were killed instantly and 53 went missing and presumed dead.

Despite claims from terrorist groups, the blast was initially thought to have been an accident caused by a gas explosion. However, after divers righted the ferry five months after it had sunk, they found evidence of a bomb blast. A man called Redendo Cain Dellosa also admitted to planting the bomb on board for Abu Sayyaf.

Philippine president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo announced on October 11, 2004 that investigators had concluded the explosion was caused by a bomb.[131] She said six suspects had been arrested in connection with the bombing and that the masterminds, Khadaffy Janjalani and Abu Sulaiman, have been killed. But the ASG continues to pose a threat to Philippine security.[132]

Supporters and funding

Abdurajik Abubakar Janjalani’s first recruits were soldiers of the Moro National Liberation Front (M.N.L.F.) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (M.I.L.F.). However, the M.I.L.F. and M.N.L.F. deny having links with Abu Sayyaf. Both officially distance themselves from Abu Sayyaf because of its attacks on civilians and its supposed profiteering. The Philippine military, however, has claimed that elements of both groups provide support to the Abu Sayyaf.

The group was originally not thought to receive funding from outside sources, but intelligence reports from the United States, Indonesia and Australia have found intermittent ties to the Indonesian Jemaah Islamiyah terrorist group,[133] and the Philippine government considers the Abu Sayyaf as a part of Jemaah Islamiyah.[35] The government also notes that initial funding for ASG in the 1990s came from al-Qaeda through the brother-in-law of Osama bin Laden, Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, through Islamic charities in the region.[35][134][135][136][137]

Al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorist Ramzi Yousef operated in the Philippines in the mid-1990s and trained Abu Sayyaf soldiers.[138] The 2002 edition of the United State Department’s Patterns of Global Terrorism mention links to Al-Qaeda.

Continuing ties to Islamist groups in the Middle East indicate that al-Qaeda may be continuing support.[28][139][140]

As of mid 2005, Jemaah Islamiyah personnel reportedly had trained about 60 Abu Sayyarf cadre in bomb assembling and detonations.[141][142][143]

Funding

The group obtains most of its financing through ransom and extortion.[144] One report estimated its revenues from ransom payments in 2000 alone between $10 and $25 million. According to the State Department, it may also receive funding from radical Islamic benefactors in the Middle East and South Asia.

It was reported that Libya facilitated ransom payments to Abu Sayyaf. Libya was also suggested that Libyan money could possibly be channeled to Abu Sayyaf.[145]

Russian intelligence agencies connected with Victor Bout's planes have reportedly provided Abu Sayyaf with arms.[146][147]

Military action against

The military has intensified its intelligence operation against the Abu Sayyaf following the arrest of a Filipino-American allegedly selling illegal weapons to the Al-Qaeda linked group. Security forces have arrested Victor Moore Infante in Zamboanga for selling weapons to the extremist group. The 34-year-old man was tagged by authorities as "one of the United States most wanted fugitives."

His arrest was made secret and announced by the Bureau of Immigration and Deportation. Infante, who was reported to have traveled to Basilan, a stronghold of the Abu Sayyaf, had been deported to Guam. Federal agents escorted the Filipino-American, who was also suspected of planning to smuggle illegal drugs to the Philippines. United States authorities have issued a warrant for the arrest of Infante in New York after Customs men in July 2003 seized one of his package from Oakland containing weapons’ parts addressed to his safehouse in Zamboanga City.

"His arrest and deportation is another big step in our campaign against terrorism because this man is known to have aided the Abu Sayyaf in acquiring weapons used by the group in committing atrocities against our soldiers and civilians," Philippine immigration chief Andrea Domingo said in a statement.

Criticism

The Libyan envoy accused the group of inhumanity and violating the tenets of Islam by holding innocent people. Abdul Rajab Azzarouq, former ambassador to the Philippines, criticised the kidnappers for holding people who have nothing to do with the conflict. The hostage-takers should not use religion as a reason to keep the hostages isolated from their families, he said.

Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi in Qatar has denounced the kidnapping and killings committed by the Abu Sayyaf towards civilians and foreigners, asserting that they are not part of the dispute between the Abu Sayyaf and the Philippines government. He stated that it is shameful to commit such acts in the name of the Islamic faith, saying that such acts produce backlashes against Islam and Muslims worldwide. It is known that Qaradawi supports the rights of Muslims in Philippines. Qaradawi spoke of the importance of education in the life of Muslims, stating that educational institutions in the Muslim world should review their educational philosophy in order that it may reflect Islamic values aiming to create pious Muslims good to themselves and non-Muslims as well.

The Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) condemned the Sipadan kidnapping and offered to help secure their release. OIC Secretary General Azeddine Laraki who represents the world's largest Islamic body, told the Philippine government he was prepared to send an envoy to help save the hostages and issued a statement condemning the rebels. "The Secretary General has pointed out that this operation and the like are rejected by divine laws and that they are neither the appropriate nor correct means to resolve conflicts," the statement said.

List of attacks attributed to Abu Sayyaf

2000

- April 23 – Abu Sayyaf gunmen raid the Malaysian diving resort of Sipadan, off Borneo and flee across the sea border to their Jolo island stronghold with 10 Western tourists and 11 resort workers.

- May 27 – The kidnappers issue political demands including a separate Muslim state, an inquiry into alleged human rights abuses in Sabah and the restoration of fishing rights. They later demand cash multimillion-dollar ransoms.

- July 1 – Filipino television evangelist Wilde Almeda of the Jesus Miracle Crusade (J.M.C.) and 12 of his followers visited the Abu Sayyaf headquarters. A German journalist is seized the following day.

- July 9 – A three-member French television crew was abducted.

- August 27 – French, South African and German hostages are freed.

- August 28 – United States Muslim convert Jeffrey Schilling is abducted.

- September 9 – Finnish, German and French hostages are freed.

- September 10 – Abu Sayyaf raids Pandanan island near Sipadan and seizes three Malaysians.

- September 16 – The government troops launch military assault against Abu Sayyaf in Jolo. Two kidnapped French journalists escape during the fighting.

- October 2 – J.M.C. Evangelist Wilde Almeda and 12 "prayer warriors" were released.

- October 25 – Troops rescue the three Malaysians seized in Pandanan.

2001

- April 12 – Jeffrey Schilling is rescued, leaving Filipino scuba diving instructor, Roland Ullah, in the gunmen's hands.

- May 22 – Suspected Abu Sayyaf gunmen raid the luxurious Pearl Farm beach resort on Samal island in southern Philippines, killing two resort workers wounding three others, but no hostages were taken.

- May 28 – Suspected Abu Sayyaf gunmen raid the Dos Palmas resort off the western Philippines island of Palawan and seize 18 hostages including a United States couple and former Manila Times owner Reghis Romero. Arroyo rules out ransom and orders the military to go after the kidnappers.

- May 29 – Malacañang imposes a news blackout in Basilan province where the Abu Sayyaf are reported to have gone.

- May 30 – United States Department Spokesman Philip Reeker calls for the "swift, safe and unconditional release of all the hostages." An Olympus camera and an ATM card of one the hostages are found in Cagayan de Tawi-Tawi island. Pictures of Abu Sayyaf leaders are released to media by the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

- May 31 – The military fails to locate the bandits and the hostages despite search and rescue operations in Jolo, Basilan and Cagayan de Tawi-Tawi.

- June 1 – Military troops engage Abu Sayyaf bandits in Tuburan town in Basilan. Abu Sayyaf spokesman Abu Sabaya threatens to behead two of the hostages.

- June 2 – Abu Sayyaf invaded Lamitan town and seize the José Maria Torres Memorial Hospital and the Saint Peter's church. Soldiers surround the bandits and engage them in a day-long firefight. Several hostages, including businessman Reghis Romero, were able to escape. Witnesses say the bandits escape from Lamitan at around 5:30 in the afternoon, taking four medical personnel from the hospital.

- June 3 – Soldiers recover the decapitated bodies of hostages Sonny Dacquer and Armando Bayona in Barangay Bulanting.

- June 4 – Military officials ask for a state of emergency in Basilan. President Gloria Arroyo turns the request down.

- June 5 – At least 16 soldiers are reported killed and 44 others wounded during a firefight between government troops and Abu Sayyaf members in Mount Sinangkapan in Tuburan town. President Arroyo promises 5 million pesos to the family of retired Col. Fernando Bajet for killing Abu Sayyaf leader Abu Sulayman on June 2, 2000. Abu Sayyaf leaders contact a government designated intermediary for possible negotiations.

- June 6 – Abu Sayyaf leader Abu Sabaya tells Radio Mindanao Network that United States hostage Martin Burnham sustained a gunshot wound on the back during a recent exchange of gunfire.

2002

- July 21 – A provincial governor and three others were wounded when fighters of the Abu Sayyaf ambushed them in the southern Philippines, the military said.

- August – Six Filipino Jehovah's Witnesses were kidnapped and two of them were beheaded.[148]

- October 2 – One American serviceman was killed and another seriously injured by a bomb blast in Zamboanga City.[149]

2003

- February 12 – The Philippines expelled an Iraqi diplomat, accusing the envoy of having ties to the Abu Sayyaf terrorist group. Second Secretary Husham Husain has been given 48 hours to leave the country, according to a statement by Philippine Foreign Secretary Blas Ople. The government said it had intelligence that the Iraqi diplomat has ties to the Islamic extremist group. The decision was taken more than a month before the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

- March 5 – Abu Sayyaf claimed responsibility for the bombings in Davao International Airport in the southern Philippines, killing 21 and injuring 148.[150]

2004

- February 24 – A bomb explodes on Superferry 14 off the coast of Manila, causing it to sink and killing 116 people. This attack is the worst terrorist attack at sea.

- April 9 – A key leader of the Islamic terrorist group Abu Sayyaf was killed, along with five of his men, during a gun battle with government troops in the southern Philippines. Hamsiraji Sali and his men were killed when a platoon of the Philippine army's elite Scout Rangers, who had been on the terrorists' trail, attacked them around midday on the island of Basilan, an Abu Sayyaf stronghold about 885 kilometres, or 550 miles, south of the capital, Manila. Four government soldiers, including a commanding officer, were injured.

- April 10 – Around 50 prisoners including many suspected members of the Abu Sayyaf escaped from jail in the southern Philippines, the officials said. Three of the escaped prisoners were later killed and three others have since been recaptured, while three jail guards were wounded in the incident on the island of Basilan. They still did not have a full headcount of those who escaped, but local army commander Colonel Raymundo Ferrer said 53 of the 137 prisoners in the jail on the outskirts of Isabela City had broken out.[151]

2005

- February 14 – The Valentine's Day bombings took place in three major cities of the Philippines namely; Makati City, Davao City and General Santos City. The incidents claimed numerous lives (including children), injuries and big amount of damaged properties. Immediately after an hour there was a claimed coming from the Abu Sayyaf Chieftain Khadaffy Janjalani and Abu Solaiman via media interview that the bombings were the terrorists' Valentines gift to the lady in Malacanang President Gloria Arroyo and to the citizenry to praise their belief. This was recorded as terrorist attack that caused the biggest downfall effects in the Philippine economic history in terms of tourism industry, foreign investors and socioeconomic undertakings of the people. The issuance of travel advisories from numerous nations was paramount after the incident.

- March 15 – Several Abu Sayyaf top leaders attempted to escape from the Camp Bagong Diwa in Bicutan, Taguig City. They killed 4 government soldiers in revenge of killing his 2 men. They barricaded the S.I.C.A compound. This started the Bagong Diwa siege. 29 hours later, the Special Action Force of the Philippine National Police sieges the compound, killing 22 men, including its leaders.

- November 17 – A prominent leader of the Islamist group Abu Sayyaf, Jatib Usman, has been killed in ongoing clashes between rebels and the military. Usman was confronted in the most southeastern province of Tawi-Tawi, an island region which is close to the Borneo coast of Malaysia.[152]

2006

- February 3 – Suspected Abu Sayyaf gunmen knocked on the door of a farm in Patikul, Mindanao and opened fire after asking residents if they were Christians or from another religion. Six people are confirmed dead, including a nine-month baby girl and five others are seriously wounded.

- March 20 – Declassified documents seized from Saddam Hussein’s government were said to have revealed that Al-Qaeda agents financed by Saddam entered the Philippines through the country’s southern backdoor.[153]

- September 19 – A Filipino Marine officer was killed after the government forces encountered a large group of Abu Sayyaf terrorists earlier day in the outskirts of Patikul town in Sulu, southern Philippines, a military official reported. Five Marine soldiers also were wounded in the clash with some 80 terrorists believed to be led by Abu Sayyaf leader Radullan Sahiron, alias commander Putol, one of the top terrorist leader based in Sulu province, said the spokesman.

2007

- January 17 – Abu Sayyaf leader, Abu Sulaiman is killed in a gun battle against the Philippine Army in Jolo.[154]

- July 11 – Eight Filipino government soldiers were killed, nine others injured and six missing following a gun battle against Abu Sayyaf soldiers, supported by armed villagers in the southern island province of Basilan, according to a military source.

- August – The military said it lost 26 soldiers and killed around 30 militants in three days of fighting on the volatile island of Jolo, in the beginning of month. The heaviest toll occurred after militants ambushed a military convoy.[155]

2008

- January 17 – Abu Sayyaf militants raided a convent in Tawi-Tawi and killed a Catholic missionary during a kidnapping attempt.[156]

- February 14 – Failed assassination plot of the President of the Philippines, Gloria Arroyo.

- June 8 – ABS-CBN Journalist Ces Drilon and her TV Crew kidnapped. 10 days later they were released after families paid a portion of the ransom.

- September 23 – A mid-level leader of the Abu Sayyaf group and a follower surrendered to the Marine Battalion Landing Team-5 (MBLT-5) in Sulu province. Colonel Eugenio Clemen, chief of the 3rd Marine Brigade, identified the bandits who surrendered as Hadjili Hari and Faizal Dali, his son-in-law.[157]

2009

- January 15 – Three Red Cross officials, Swiss Andreas Notter, Filipino Mary Jane Lacaba and Italian Eugenio Vagni were kidnapped. Andreas Notter and Mary Jane Lacaba were released four months later.[158] Eugenio Vagni was released six months later on July 12.[159]

- April 14 – Abu Sayyaf militants executed Cosme Aballes, one of two hostages they took during a raid on a Christian community in Lamitan City in Basilan on Good Friday, the military said. The bandits were with members of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and of kidnap for ransom groups. Aballes and Ernan Chavez were taken by at least 40 Abu Sayyaf, rogue M.N.L.F. rebels and KFR elements when they raided Sitio Arco in Lamitan City. On their way out, the kidnappers shot dead a resident, Jacinto Clemente.

- May 18 – Abu Sayyaf militants in Basilan beheaded a 61-year-old man who was abducted from this city about three weeks before, the police said.[160]

- July 12 – The Italian Red Cross hostage, Eugenio Vagni, was released.[161]

- August 12 – A group of Abu Sayyaf militants and members of the M.N.L.F. ambushed a group of A.F.P. (Armed Forces of the Philippines) soldiers as they conducted a clearing operation in the mountains of Tipo-Tipo, Basilan. 23 A.F.P. soldiers were killed in the engagement, 20 of which were members of the Philippine Marines Corps. In addition, 31 Abu Sayyaf militants were killed in an initial body count.[162]

- September 21 – A.F.P. overran a camp in the south belonging to the Abu Sayyaf, killing nearly 20 militants. 5 A.F.P. were wounded.[163]

- September 29 – Two United States soldiers were killed in Jolo, near the town of Indanan, by Abu Sayyaf militants.[164]

- October 14 – An Irish-born priest was kidnapped from outside his home near Pagadian city in Mindanao.[165] He was released on November 11, 2009.[166]

- November 9 – A school teacher in Jolo was captured on October 19 and beheaded by Abu Sayyaf militants.[167]

- November 10 – Abu Sayyaf militants captured several Chinese and Filipino nationals in Basilan.[168][169]

2010

- January 21 – Suspected Abu Sayyaf militants detonated a bomb near the house of a Basilan province mayor. One teenager was injured.[170]

- February 21 – One Abu Sayyaf senior leaders, Albader Parad, has been killed.[171]

- February 27 – Suspected Abu Sayyaf militants killed one militiaman and 12 civilians in Maluso.[172]

- March 16 – Suspected Abu Sayyaf militants killed a police officer in Zamboanga.[173]

2011

- January 12 – Four traveling merchants and a guide were killed and one wounded when suspected Abu Sayyaf militants ambushed them in Basilan.[174]

- January 18 – One soldier was killed when government forces clashed with Abu Sayyaf militants in the province of Basilan.[175]

- December 5 - Australian national Warren Rodwell was shot through the hand when kidnapped from his home at Ipil, Zamboanga Sibugay. He was released on March 23, 2013 in exchange for cash.[176]

2012

- February 1 – Dutch national Ewold Horn and Swiss citizen Lorenzo Vinciguerra, both birdwatchers, were kidnapped during a research trip in Tawi-Tawi. On December 6, 2014, Lorenzo Vinciguerra was rescued after he escaped from his captors when the troops under the Joint Task Force Sulu attacked the Abu Sayyaf group about 5:20 a.m. However, one of the ASG shot and wounded the Swiss national as he was escaping.[177] As of that date, Dutch national Ewold Horn is still in captivity by the Abu Sayyaf.[178][179]

2013

- May 27 – At least 7 militants and 7 marines were killed when the government forces tried to rescue 6 hostages.[180]

- November 15 – Abu Sayyaf gunmen raid the Malaysian resort in Pom Pom, off Semporna, killing one Taiwanese tourist and flee across the sea border to Sulu Archipelago with another Taiwanese hostage.[105][106] The hostage was later rescued by the Philippines security forces in Sulu Province.[110]

2014

- April 2 – Abu Sayyaf gunmen raid another Malaysian resort in Semporna and flee across the sea border to Sulu Archipelago with a Chinese and Filipino hostages.[111][112][113] The two hostages were later rescued on May 31 with a collaboration by the Malaysian and the Philippines security forces.[114][115]

- April 25 – Abu Sayyaf gunmen abduct a retired German doctor and his girlfriend from their yacht near the island of Palawan. They are released on October 17. The group claims to have collected a 5,6 Mio $ ransom from the German government.[181]

- May 6 – Five Abu Sayyaf gunmen raid a Malaysian fish farm in Baik Island near the shores of Silam and kidnap the fish farm manager.[116] The hostage was later taken to the Jolo island in the Sulu Archipelago.[117] He was later freed on July with the help of Malaysian negotiators.[118]

- June 16 – Two Abu Sayyaf gunmen raid a Malaysian fish farm and kidnapped a Chinese fish farm manager and one Filipino in Kampung Air Sapang, Kunak, Sabah.[119][120] The Filipino hostage managed to escape while the fish farm manager has been taken away to Jolo.[121][122][123] The fish farm manager was later released on December 10.[124]

- June 27 – Abdul Basit Usman, a bomb maker with links to Abu Sayyaf, reportedly is training others to carry out bombings in the Philippines.[182]

- July 28 – Abu Sayyaf members ambush a civilian vehicle loaded with celebrators of Eid in Sulu, killing 21 people.[183]

- August 20 – There are alleged reports that Abu Sayyaf members are training in Iraq under the Islamic State.[184] Within this time, Isnilon Totoni Hapilon's group pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant[185] followed by Radullan Sahiron. ISIS accepted their pledge.

2015

- February – Military intelligence said that members of Jemaah Islamiyah are training Abu Sayyaf members in Sulu.

- May 15 – Four Abu Sayyaf members abducted two people in a resort in Sandakan, Malaysia and brought them to Parang, Sulu.[126][127]

- May – Abu Sayyaf members abducted 2 Coast Guard personnel and a barangay captain in Aliguay Island, a tourist destination in Zamboanga del Norte near Dapitan City. The captain was found beheaded later in Sulu. The Coast Guard personnel later escaped when the group encountered a battalion of Marines and some members of the Scout Rangers, an encounter that left 15 ASG members dead.[186]

- September 21 – Canadians Robert Hall, John Ridsdel, Norwegian Kjartan Sekkingstad and a Filipina woman named Maritess Flor were kidnapped by dozen armed men in a resort, Holiday Oceanview Resort along Island Garden City of Samal, Davao del Norte. Hostage videos have been released, however they still remain imprisoned by the militants[187]

- November 9 – One of the Malaysian kidnapped victims been released after ransom been paid.[128]

- November 17 – While another Malaysian hostage was beheaded after ransom demands was not met.[129][130]

- Late December, ISIL officially puts Abu Sayyaf as their direct affiliate.

2016

- January 14 – A member of Abu Sayyaf who was believed to have been involved in the 2000 kidnappings over Sipadan was arrested by Philippine authorities.[188]

- February 6 – Another Abu Sayyaf member who been alleged has link to the 2000 kidnappings over Sipadan and Davao Pearl Farm incidents was killed during a clash with Philippine police and military personnel who out to arrest him in Indanan, Sulu.[189]

See also

References

- ↑ Stanford University: "Abu Sayyaf Group" retrieved August 17, 2015

- ↑ killed, December 8, 1998

- ↑ Killed, September 4, 2006

- ↑ rewardsforjustice.net Archived February 25, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "FBI — RADDULAN SAHIRON". FBI. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- 1 2 "Senior Abu Sayyaf leader swears oath to ISIS". Rappler. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ David Von Drehle (February 26, 2015). "What Comes After the War on ISIS". TIME.com. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf sub-leader killed in Sulu encounter". InterAksyon.com. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "US To Dissolve Anti-Terror Group, JSOTF-P, In Philippines After 10 Years Of Fighting Abu Sayyaf". Sneha Shankar. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- 1 2 Miani 2011, p. 74.

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf declared as terrorist organization in Philippines". Iran Daily. 10 September 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ "Australian National Security, Terrorist organisations,Abu Sayyaf Group". Australian Government. 12 July 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ "Hunt down the killers, CM tells Manila". Daily Express. 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ Joel Locsin (20 June 2015). "US govt lists NPA, Abu Sayyaf, JI among foreign terrorist organizations in PHL". GMA News. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ Rommel Banlaoi. "Al Harakatul Al Islamiyah: Essays on the Abdu Sayyaf Group" (PDF).

- ↑ Feldman, Jack. "Abu Sayyaf" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- 1 2 Rommel C. Banlaoi. "Maritime Terrorism in Southeast Asia: The Abu Sayyaf Threat".

- ↑ FBI Updates Most Wanted Terrorists and Seeking Information – War on Terrorism Lists, FBI national Press Release, February 24, 2006 Archived August 30, 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 "ABU SAYYAF GROUP (ASG)". US Department of State.

- ↑ East, Robert (2013). Terror Truncated: The Decline of the Abu Sayyaf Group from the Crucial Year 2002. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 3. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ Rommel C. Banlaoi. "Abu Sayyaf Group: From Mere Banditry to Genuine Terrorism".

- 1 2 3 4 "Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)". MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base. Archived from the original on 27 August 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ↑ Martin, Gus (2012). Understanding Terrorism: Challenges, Perspectives, and Issues. Sage Publications. p. 319.

- ↑ Flashpoint, No bungle in the jungle, armedforcesjournal.com, archived from the original on October 21, 2007, retrieved November 1, 2007

- 1 2 "2 US Navy men, 1 Marine killed in Sulu land mine blast". GMA News. September 29, 2009. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

Two US Navy personnel and one Philippine Marine soldier were killed when a land mine exploded along a road in Indanan, Sulu Tuesday morning, an official said. The American fatalities were members of the US Navy construction brigade, Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) spokesman Lt. Col. Romeo Brawner Jr. told GMANews.TV in a telephone interview. He did not disclose the identities of all three casualties.

and

Al Pessin (September 29, 2009). "Pentagon Says Troops Killed in Philippines Hit by Roadside Bomb". Voice of America. Retrieved January 12, 2011. and

"Troops killed in Philippines blast". Al Jazeera. September 29, 2009. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2009. and

Jim Gomez (September 29, 2009). "2 US troops killed in Philippines blast". CBS News. Archived from the original on February 2, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2011. - ↑ Philip Oltermann. "Islamists in Philippines threaten to kill German hostages". the Guardian. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- 1 2 "Abu Sayyaf History". U.S. Pacific Command. September 21, 2006. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Who are the Abu Sayyaf". London: BBC. December 30, 2000.

- 1 2 "Funding Terrorism in Southeast Asia: The Financial Network of Al Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah" (PDF). The National Bureau of Asian Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ↑ Zachary Abuza, “Funding Terrorism in Southeast Asia: The Financial Network of Al Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah,” The National Bureau of Asian Research 14, no. 5 (December 2003): 176.

- ↑ "National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States". 2003-07-09. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

MR. GUNARATNA: Sir, Mohammad Jamal Khalifa ... arrived in the Philippines in 1988 and he became the first director, the founding director, of the International Islamic Relief Organization of Saudi Arabia.

- ↑ Giraldo, Jeanne K.; Trinkunas, Harold A. Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective. Sanford University Press. p. 120. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "Complete 911 Timeline. Mohammed Jamal Khalifa". History Commons. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ Abuza, Zachary (September 2005). Balik-Terrorism: The Return of the Abu Sayyaf (PDF). Carlisle PA: Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. p. 47. ISBN 1-58487-208-X. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

Based on IIRO documents at the PSEC, Khalifa was one of five incorporators who signed the documents of registration; another was Khalifa's wife, Alice 'Jameelah' Yabo.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Elegant, Simon (August 30, 2004). "The Return of Abu Sayyaf". Time Asia Magazine.

- ↑ "Fresh fighting in S Philippines". London: BBC. September 7, 2006.

- 1 2 "Manilla captures senior Abu Sayyaf". CNN. December 7, 2003.

- ↑ "Ex-hostage describes jungle ordeal". CNN. May 9, 2003.

- ↑ "Prominent Abu Sayyaf Commander Believed Dead". Institute for Counter-Terrorism. Archived from the original on January 5, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ↑ "Profiles of dead Abu Sayyaf leaders". London: BBC. March 15, 2005.

- ↑ "Bloody end to Manila jail break". London: BBC. March 15, 2005.

- ↑ "Blast at US Philippines army base". London: BBC. February 18, 2006.

- ↑ "US indicts Abu Sayyaf leaders". London: BBC. July 23, 2002.

- ↑ "FBI puts al-Zarqawi high on its list". CNN. February 24, 2006.

- ↑ "Tiahrt responds to the Abu Sayyaf terrorist indictments". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on September 10, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ↑ "Manila Again Denies Terror Plot Led to Postponement of Asia Summits". Voice of America (VoA). December 13, 2006. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 FlorCruz, Michelle (September 25, 2014). "Philippine Terror Group Abu Sayyaf May Be Using ISIS Link For Own Agenda". International Business Times. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ Bowden, Mark (March 1, 2007). "Jihadists in Paradise". The Atlantic.

- ↑ East, Robert (17 May 2015). Terror Truncated: The Decline of the Abu Sayyaf Group from the Crucial Year 2002. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 2. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ Fellman, Jack. "Abu Sayyaf Group" (PDF). Center for Strategic International Studies. p. 4. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ "Engine trouble and kidnappings". sailingtotem.com. June 25, 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ Bale, Jeffrey M. "The Abu Sayyaf Group in its Philippine and International Contexts". p. 50.

- ↑ "Korean kidnap victim found dead in Jolo - The Philippine Examiner". The Philippine Examiner.

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf's Korean hostage found dead in Sulu". philstar.com.

- ↑ "Kidnapped Korean found dead in Sulu". philstar.com.

- ↑ "US Hostage Freed in Philippines". CBS News. April 12, 2001.

- ↑ "Larry Thompson, Deputy Attorney General (Live Transcript)". CNN International. July 23, 2002.

- ↑ Chip Johnson (April 14, 2001). "What Was Schilling Thinking? Oblivious Oakland Man Sets Himself Up". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Gracia's enemies newsstand.blogs.com Archived June 7, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 "Manhunt" by Mark Bowden, The Atlantic, March 2007, p.54 (15)

- ↑ "Burham identifies former Abu Captors" (PDF). Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Philippines Brace for Retaliation" March 15, 2005, Associated Press.

- ↑ ''In the Presence of My Enemies''. Google Books. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf abducted 20 journalists since 2000". Rp3.abs-cbnnews.com. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ Alipala, Julie (January 17, 2009). "3 Red Cross kidnap victims alive, safe". Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ↑ "Freed Australian Philippines hostage Warren Rodwell wants a new wife News Limited Online". News.com Online. June 16, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Aussie Warren Rodwell holds no hope for his release in the Philippines - The Australian Online". The Australian Online December 28, 2012. December 28, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Warren Rodwell begs for life after being kidnapped by Philippines rebels - Daily Mail Online". Mail Online (London). January 5, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 472 Days Captive of the Abu Sayyaf". Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Relief after release of former Tamworth man Warren Rodwell". The Northern Daily Leader March 23, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ↑ Whaley, Floyd (March 23, 2013). "Kidnapped Australian Is Freed in Southern Philippines". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Hostage survivor Warren Rodwell tells of hunger, sickness during 472 days held captive by Muslim militants". Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "BBC News - Abu Sayyaf release Australian hostage Warren Rodwell". BBC News. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Warren Rodwell tells of how he survived as a hostage in the Philippines - News Corp Online". News.com.au Online. October 11, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Hours from being beheaded, hostage Warren Rodwell is coming home to Australia". The Daily Telegraph March 24, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ↑ Portal:Current events/2012 January 5

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf bandits free Aussie for P7M". Global Nation Inquirer March 24, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Kidnappers send photos showing Rodwell still alive". Sydney Morning Herald January 3, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Kidnap blackout unwise: expert". Sydney Morning Herald December 12, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Kidnapped Australian Warren Rodwell freed by Philippines terrorists after 15 months". Sydney Morning Herald March 23, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Freed hostage Warren Rodwell says he is overwhelmed and grateful for support". NewsComAu. March 26, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Kidnapped Australian Warren Rodwell freed by Philippines terrorists after 15 months,". Sydney Morning Herald March 23, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Video - msn Australia, with Outlook.com, Skype, and news". Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Philippines militants free Warren Rodwell". The Australian March 23, 2013. March 23, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Released hostage Warren Rodwell to return home". The Daily Telegraph March 25, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Media Release: AFP members recognised for bravery and excellence". Australian Federal Police March 27, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ↑ Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. "Warren Rodwell". Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "472 Days Captive of the Abu Sayyaf - The Survival of Australian Warren Rodwell". Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Abducted but not by Mad Cowboy Disease". Mint Magazine. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ↑ "ABOUT RAPPLER". Rappler.

- ↑ "From Bin Laden to Facebook: 10 Days of Abduction, 10 Years of Terrorism". Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Global Jihad and the Tactic of Terror Abduction : A Comprehensive Review of Islamic Terrorist Organizations". Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Officials seek negotiator for talks with kidnappers". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Mindanao Examiner - Warren Rodwell kidnapper arrested in Zamboanga province". Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Media Release: NBI files charges vs Abu bandits for Gensan bombing". ABS-CBNnews.com April 17, 2015. Retrieved Aug 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Media Release: EX-COP ARRESTED IN MALAYSIA FOR KIDNAPPING OF AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL". APNP-AKG Press Release May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Suspect in 2012 Aussie kidnapping in Ipil nabbed". Zamboanga Times Aug 14, 2015. Retrieved Aug 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Abu Sayyafs’ ransom courier falls". Sun Star Zamboanga Aug 13, 2015. Retrieved Aug 16, 2015.

- 1 2 "Abu Sayyaf kidnappings, bombings and other attacks". GMA News. August 23, 2007. Archived from the original on April 22, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ↑ "jmcim.org". Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ FREEMAN WASHINGTON (September 10, 2000). "Abu Sayyaf Muslim rebels raped Sipadan dive tourist hostages". cdnn.info. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ↑ "BBC news.uk". BBC News. August 28, 2000. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Sipadan Timeline". cdnn.info. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Note : August 10, 2000, Philippine Daily Inquirer, Source says some groups took cuts on P9-M payoff, by Donna S. Cueto,". Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Pom Pom Island: Tourist killed, wife kidnapped". Emirates 24/7. November 16, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- 1 2 "Militant group Abu Sayyaf behind Taiwanese woman's kidnapping". Want China Times. December 22, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Kidnapping victim thanks helper for securing release". Focus Taiwan. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Abducted Taiwanese woman Evelyn Chang found in Southern Philippines". South China Morning Post. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ Lewis, Leo (April 5, 2014). "Snatched Tourist Faces Torment in Jungle". The Times of London. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- 1 2 Farik Zolkepli (December 20, 2013). "Semporna kidnap: Rescued - Taiwanese tourist kidnapped from Pom Pom island resort (Update)". The Star. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Muguntan Vanar (April 4, 2014). "Semporna resort kidnap: Abductors also involved in Pom-Pom and Sipadan incidents, says Esscom chief". The Star. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- 1 2 "Abu Sayyaf men abduct 2 in Malaysia–officials". Philippine Daily Inquirer. April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- 1 2 Muguntan Vanar (April 3, 2014). "Two abducted from resort off Semporna". The Star. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- 1 2 "Kidnapped tourist, resort worker rescued in Malaysia". Channel NewsAsia. May 31, 2014. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- 1 2 "Women abducted from Malaysian resort released". Al Jazeera English. May 31, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- 1 2 "Another abduction in Sabah". Free Malaysia Today. May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- 1 2 Muguntan Vanar; Stephanie Lee (May 8, 2014). "Officials get reports that Chinese national has been taken to Jolo". The Star. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- 1 2 Ruben Sario; Stephanie Lee (July 11, 2014). "Malaysian negotiators rescue fish farm manager from Abu Sayyaf gunmen". The Star. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- 1 2 Charles Ramendran and Bernard Cheah (June 16, 2014). "Two more kidnapped in Sabah". The Sun. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- 1 2 "Kunak kidnap: "Don't disturb my wife. I will follow you"". Bernama. The Star. June 16, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- 1 2 "Fish farm worker manages to escape armed kidnappers in Sabah". The Star/Asia News Network. The Straits Times. June 16, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- 1 2 "Hostage who escaped sought". Daily Express. June 18, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- 1 2 "Kidnappers contact fish breeder's wife". The Star. June 20, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- 1 2 "Fish breeder released by Abu Sayyaf". The Sun. December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ PK Katharason; Muguntan Vanar; Ruben Sario; Stephanie Lee; Philip Golingai (June 22, 2014). "Muktadir kin - mastermind behind kidnaps?". The Star. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- 1 2 "Kidnapping incident in Sabah recurs". The Borneo Post. May 16, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- 1 2 "Police: Abu Sayyaf linked to Sabah kidnap". GMA News. May 15, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- 1 2 "Sabah hostage released by Abu Sayyaf gunmen". The Star/Asia News Network. Philippine Daily Inquirer. November 9, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Muguntan Vanar; Stephanie Lee (November 17, 2015). "Malaysian hostage Bernard Then beheaded". The Star. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- 1 2 "Demand for higher ransom led to beheading". The Star. November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ↑ Rommel C. Banlaoi. "Abu Sayyaf Group: Threat of Maritime Piracy and Terrorism".

- ↑ Banlaoi, Rommel (2010). Philippine Security in the Age of Terror. New York and London: CRC Press Taylor and Francis. pp. 1–358. ISBN 978-1-4398-1550-2.

- ↑ "Ferry bomb terror suspect held in Manila". CNN. August 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Air raids hit Philippines rebels". London: BBC. November 20, 2004.

- ↑ "AsiaWeek: 08.31.1999". AsiaWeek. August 31, 1999.

- ↑ "The Abu Sayyaf-Al Qaeda Connection-Abu Sayyaf Terrorist Group Alleged to Have Links to Al Qaeda". abc News International. Retrieved December 20, 2001.

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf survives US-backed Philippine crackdown". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ↑ Banlaoi, Rommel (2004). War on Terrorism in Southeast Asia. Quezon City: Rex Book Store. pp. 1–235. ISBN 971-23-4031-7.

- ↑ "Gunfight in philippine bomber hunt". CNN. August 10, 2003.

- ↑ "Bin Laden Funds Abu Sayyaf Through Muslim Relief Group". Philippine Daily Inquirer. August 9, 2000.

- ↑ Mogato, Manny, "Philippine rebels linking up with foreign jihadist." Reuters News, August 21, 2005.

- ↑ Del Puerto, Luige A. "PNP [Philippine National Police]: Alliance of JI, RP terrorists strong." Philippines Daily Inquirer (internet version), November 20, 2005

- ↑ Vaughn, Bruce (2009). Terrorism in Southeast Asia. DIANE Publishing. p. 17. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ Rommel C. Banlaoi. "The Sources of Abu Sayyaf's Resilience in the Southern Philippines".

- ↑ Niksch, Larry (January 25, 2002). "Abu Sayyaf: Target of Philippine-U.S. Anti-Terrorism Cooperation" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Federation of American Scientists.

- ↑ The deadly convenience of Victor Bout. ISN Eth Zurich. June 24, 2008

- ↑ Background: the life of Viktor Bout. The Guardian. March 6, 2009

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf Group (Philippines, Islamist separatists)". Council on Foreign relations. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ↑ "Philippines blast targets US troops". BBC News. October 2, 2002. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Philippines airport bomb kills 21". Archived from the original on March 6, 2003. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ 'Abu Sayyaf members escape': World: News: News24 Archived December 2, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Philippines: Islamic Militants Resume Battles in South". westernresistance.com. November 17, 2005. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ↑ "Saddam linked to Abu Sayyaf". Manila Standard. March 20, 2006. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ↑ Abu Sulaiman, a leader of the Abu Sayyaf rebel group, has been killed The Associated Press, January 17, 2007 Archived January 24, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Philippine clashes leave 50 dead". BBC News. August 10, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ↑ manilatimes.net Archived February 12, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "www.gmanews.tv". gmanews.tv. September 23, 2008. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Inquirer.Net". Newsinfo.inquirer.net. April 19, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "www.icrc.com". icrc.com. July 12, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Inquirer.Net". Newsinfo.inquirer.net. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Vagni finally released from Abu Sayyaf captivity in Sulu". GMA NEWS.TV.

- ↑ Conde, Carlos H. (August 14, 2009). "www.nytimes.com". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ Conde, Carlos H. (September 22, 2009). "www.nytimes.com". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Bbc News.Uk". BBC News. September 29, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "www.cnn.com". CNN. October 11, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Fr Michael Sinnott freed". RTÉ News. November 12, 2009.

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf behead Jolo head teacher". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 11, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ↑ "Abu Sayyaf behind latest Basilan abduction -AFP". GMA NEWS.TV. Archived from the original on November 12, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ↑ "AFP blames Abu Sayyaf for kidnapping in Basilan". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 11, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Bomb explodes near Basilan mayor's house". Sun.Star. January 21, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Philippines kills Abu Sayyaf most-wanted Albader Parad". CSMonitor.com. February 22, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ Reyes, Jewel. "2 more die in Abu Sayyaf attack in Basilan". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ Worldwide Incidents Tracking System

- ↑ "Five killed by suspected Abu Sayyaf bandits in Basilan | The Manila Bulletin Newspaper Online". Manila Bulletin. January 12, 2011. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ People's Tonight (March 24, 2012). "Sports | Daily news from the Philippines". Journal.com.ph. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Freed Australian Philippines hostage Warren Rodwell wants a new wife News Limited Online". News.com Online. June 16, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Kidnapped Swiss bird watcher escapes from Abu Sayyaf". December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ "The men Rodwell leaves behind with the Abu Sayyaf". March 24, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Police search for German hostages held by Abu Sayyaf". September 25, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ↑ Whaley, Floyd. "Abu Sayyaf". The New York Times. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse. "The bloodstained trail of the Abu Sayyaf". ABS-CBN News.

- ↑ "PNoy alerts Duterte on potential terror threat". ABS-CBN News. June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Philippine Star: "Abu Sayyaf bandits massacre 21 civilians in Sulu" By Roel Pareño July 28, 2014

- ↑ Rappler News: "ISIS threats and followers in the Philippines - The Philippine government has to implement a strong preventive counter measure before this threat develops into a many-headed monster that is hard to defeat" BY Rommel Banlaoi August 05, 2014

- ↑ International Business Times: "Malaysia Declares 'Red Alert' in Sabah as Filipino Terror Group Abu Sayyaf Pledge Allegiance to Isis" By Jack Moore September 22, 2014

- ↑ Ang Balitamg Davao: "[Video] Barangay captain beheaded by alleged Abu Sayyaf members" August 12, 2015

- ↑ "3 foreigners, Filipina kidnapped on Samal Island". CNN Philippines. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ↑ Bong Garcia (14 January 2016). "Authorities arrest Sipadan, Malaysia raider". Sun.Star. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Jaime Sinapit (7 February 2016). "Suspect in Sipadan, Davao Pearl Farm incidents killed in Sulu clash". Interaksyon. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abu Sayyaf. |

- Most Wanted Terrorists, Federal Bureau of Investigation, US Department of Justice

- Council on Foreign Relations: Abu Sayyaf Group (Philippines, Islamist separatists)

- Reward For Information (on five ASG members), Rewards for Justice Program, US Department of State

- Profile: Abu Sayyaf, Public Broadcasting Service

- Philippines the second front in war on terror?, Asia Times Online

- Looking for al-Qaeda in the Philippines

- Balik-Terrorism: The Return of Abu Sayyaf (PDF), Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College

- Philippines Terrorism: The Role of Militant Islamic Converts

- The bloodstained trail of the Abu Sayyaf, Agence France-Presse

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||