Walther Nernst

| Walther Nernst | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Walther Hermann Nernst 25 June 1864 Briesen, West Prussia (now Wąbrzeźno, Poland) |

| Died |

18 November 1941 (aged 77) Zibelle, Lusatia, Germany (now Niwica, Poland) |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions |

University of Göttingen University of Berlin University of Leipzig |

| Alma mater |

University of Zürich University of Berlin University of Graz University of Würzburg |

| Doctoral advisor | Friedrich Kohlrausch |

| Other academic advisors | Ludwig Boltzmann |

| Doctoral students |

Sir Frances Simon Richard Abegg Irving Langmuir Leonid Andrussow Karl Friedrich Bonhoeffer Frederick Lindemann William Duane |

| Other notable students |

Gilbert N. Lewis Max Bodenstein Robert von Lieben Kurt Mendelssohn Theodor Wulf Emil Bose Hermann Irving Schlesinger Claude Hudson |

| Known for |

Third Law of Thermodynamics Nernst lamp Nernst equation Nernst glower Nernst effect Nernst heat theorem Nernst potential Nernst–Planck equation |

| Influenced | J. R. Partington |

| Notable awards |

Nobel Prize in chemistry (1920) Franklin Medal (1928) |

|

Signature  | |

Walther Hermann Nernst, ForMemRS[1] (25 June 1864 – 18 November 1941) was a German physicist who is known for his theories behind the calculation of chemical affinity as embodied in the third law of thermodynamics, for which he won the 1920 Nobel Prize in chemistry. Nernst helped establish the modern field of physical chemistry and contributed to electrochemistry, thermodynamics and solid state physics. He is also known for developing the Nernst equation.

Life and career

Early years

Nernst was born in Briesen in West Prussia (now Wąbrzeźno, Poland) as son of Gustav Nernst (1827–1888) and Ottilie Nerger (1833–1876).[2][3] His father was a country judge. Nernst had three older sisters and one younger brother. The third sister died due to cholera. Nernst went to elementary school at Graudenz. He studied physics and mathematics at the universities of Zürich, Berlin, Graz and Würzburg, where he received his doctorate 1887. In 1889, he finished his habilitation at University of Leipzig.

Personal attributes

It was said that Nernst was mechanically minded in that he was always thinking of ways to apply new discoveries to industry. Nernst's hobbies included hunting and fishing.[4]

Family history

Nernst married in 1892 to Emma Lohmeyer with whom he had two sons and three daughters. Both of Nernst's sons died fighting in World War I. He was a colleague of Svante Arrhenius, and suggested setting fire to unused coal seams to increase the global temperature. He was a vocal critic of Adolf Hitler and Nazism, and his three daughters married Jewish men. In 1933, the rise of Nazism led to the end of Nernst's career as a scientist. Nernst died in 1941 and is buried near Max Planck, Otto Hahn and Max von Laue in Göttingen, Germany. [5]

Career

After some work at Leipzig, he founded the Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry at Göttingen.

Nernst invented, in 1897 an electric lamp, using an incandescent ceramic rod. His invention, known as the Nernst lamp, was the successor to the carbon lamp of Edison and the precursor to the tungsten incandescent lamp of his student Irving Langmuir.

Nernst researched osmotic pressure and electrochemistry. In 1905, he established what he referred to as his "New Heat Theorem", later known as the Third law of thermodynamics (which describes the behavior of matter as temperatures approach absolute zero). This is the work for which he is best remembered, as it provided a means of determining free energies (and therefore equilibrium points) of chemical reactions from heat measurements. Theodore Richards claimed Nernst had stolen the idea from him, but Nernst is almost universally credited with the discovery.[6]

In 1911, with Max Planck, he was the main organizer of the first Solvay Conference in Brussels.

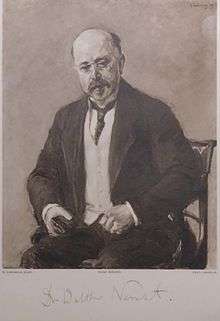

In 1912, the impressionist painter Max Liebermann painted his portrait.

In 1914 Nernst showed his support for German militarism by signing the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three. He also accepted the post of Staff Scientific Advisor in the Imperial German Army.

In 1918, after studying photochemistry, he proposed the atomic chain reaction theory. The atomic chain reaction theory stated that when a reaction in which free atoms are formed and can decompose molecules into more free atoms which results in a chain reaction. His theory is closely related to the natural process of Nuclear Fission.

In 1920, he received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in recognition of his work in thermochemistry. In 1924, he became director of the Institute of Physical Chemistry at Berlin, a position from which he retired in 1933. Nernst went on to work in electroacoustics and astrophysics.

Nernst developed an electric piano, the "Neo-Bechstein-Flügel" in 1930 in association with the Bechstein and Siemens companies, replacing the sounding board with radio amplifiers. The piano used electromagnetic pickups to produce electronically modified and amplified sound in the same way as an electric guitar.

His device, a solid-body radiator with a filament of rare-earth oxides, that would later be known as the Nernst glower, is important in the field of infrared spectroscopy. Continuous ohmic heating of the filament results in conduction. The glower operates best in wavelengths from 2 to 14 micrometers.

When Nernst was developing his third law, he read a paper of Einstein's on the quantum mechanics of specific heats at cryogenic temperautures and was so impressed that he traveled all the way to Zurich to visit him in person. Einstein's status changed dramatically after Nernst's visit. He was relatively unknown in Zurich in 1909, and people said "Einstein must be a clever fellow if the great Nernst comes all the way from Berlin to Zurich to talk to him ." [7] Nernst was the perfect instrument of Providence to provide Einstein with his dream job: A named professorship at the top university in Germany, without teaching duties, leaving him free to do research.[8]

- Nernst was highly influential at The University of Berlin.

- He was independently wealthy, due to his success with the Nernst lamp.

- When asking for private donations to fund Einstein's Chair, he could also contribute.

So, in 1914, Einstein returned to Berlin and was appointed Director of the newly created Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics and a Professor at the Humboldt University of Berlin, with a special clause in his contract that freed him from most teaching obligations.[9]

Publications

- Walther Nernst, "Reasoning of theoretical chemistry: Nine papers (1889–1921)" (Ger., Begründung der Theoretischen Chemie : Neun Abhandlungen, 1889–1921). Frankfurt am Main : Verlag Harri Deutsch, c. 2003. ISBN 3-8171-3290-5

- Walther Nernst, "The theoretical and experimental bases of the New Heat Theorem" (Ger., Die theoretischen und experimentellen Grundlagen des neuen Wärmesatzes). Halle [Ger.] W. Knapp, 1918 [tr. 1926]. [ed., this is a list of thermodynamical papers from the physico-chemical institute of the University of Berlin (1906–1916); Translation available by Guy Barr LCCN 27-2575

- Walther Nernst, "Theoretical chemistry from the standpoint of Avogadro's law and thermodynamics" (Ger., Theoretische Chemie vom Standpunkte der Avogadroschen Regel und der Thermodynamik). Stuttgart, F. Enke, 1893 [5th edition, 1923]. LCCN po28-417

See also

References

- ↑ Cherwell; Simon, F. (1942). "Walther Nernst. 1864-1941". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 4 (11): 101. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1942.0010.

- ↑ Barkan, Diana (1999). Walther Nernst and the transition to modern physical science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052144456X.

- ↑ Bartel, Hans-Georg, (1999) "Nernst, Walther", pp. 66–68 in Neue Deutsche Biographie, Vol. 19

- ↑ "Walther Hermann Nernst". foundationNobel Prize. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ Walter Nernst Biography.nobelprize.org

- ↑ Coffey, Patrick (2008). Cathedrals of Science: The Personalities and Rivalries That Made Modern Chemistry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 78–81. ISBN 0-19-532134-0.

- ↑ Stone, p. 146.

- ↑ Stone, pp. 165 ff.

- ↑ Stone, p. 165

Cited sources

- Stone, A. Douglas (2013) Einstein and the Quantum. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1491531045

Further reading

- Barkan, Diana Kormos (1998). Walther Nernst and the Transition to Modern Physical Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44456-X.

- Bartel, Hans-Georg; Huebener, Rudolf P. (2007). Walther Nernst. Pioneer of Physics and of Chemistry. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 981-256-560-4.

- Mendelssohn, Kurt Alfred Georg (1973). The World of Walther Nernst: The Rise and Fall of German Science. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-14895-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walther Nernst. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Walther Nernst |

- Katz, Eugenii. "Hermann Walther Nernst". Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- "Nernst: architect of physical revolution". Physics World. September 1999. – Review of Diana Barkan's Walther Nernst and the Transition to Modern Physical Science

- "Hermann Walther Nernst, Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1920 : Prize Presentation". Presentation Speech by Professor Gerard de Geer, President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

- Schmitt, Ulrich, "Walther Nernst". Physicochemical institute, Göttingen

- "Walther Nernst" (PDF). nobelmirror.

- Walther Nernst at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

|