Marshallian demand function

In microeconomics, a consumer's Marshallian demand function (named after Alfred Marshall) specifies what the consumer would buy in each price and income or wealth situation, assuming it perfectly solves the utility maximization problem. Marshallian demand is sometimes called Walrasian demand (named after Léon Walras) or uncompensated demand function instead, because the original Marshallian analysis ignored wealth effects.

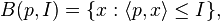

According to the utility maximization problem, there are L commodities with price vector p and choosable quantity vector x. The consumer has income I, and hence a set of affordable packages

where  is the inner product of the price and quantity vectors. The consumer has a utility function

is the inner product of the price and quantity vectors. The consumer has a utility function

The consumer's Marshallian demand correspondence is defined to be

Uniqueness

is called a correspondence because in general it may be set-valued - there may be several different bundles that attain the same maximum utility. In some cases, there is a unique utility-maximizing bundle for each price and income situation; then,

is called a correspondence because in general it may be set-valued - there may be several different bundles that attain the same maximum utility. In some cases, there is a unique utility-maximizing bundle for each price and income situation; then,  is a function and it is called the Marshallian demand function.

is a function and it is called the Marshallian demand function.

If the consumer has strictly convex preferences and the prices of all goods are strictly positive, then there is a unique utility-maximizing bundle.[1]:156 PROOF: suppose, by contradiction, that there are two different bundles,  and

and  , that maximize the utility. Then

, that maximize the utility. Then  . By definition of strict convexity, the mixed bundle

. By definition of strict convexity, the mixed bundle  is strictly better than

is strictly better than  . But this contradicts the optimality of

. But this contradicts the optimality of  .

.

Continuity

The maximum theorem implies that if:

- The utility function

is continuous with respect to

is continuous with respect to  ,

, - The correspondence

is non-empty, compact-valued, and continuous with respect to

is non-empty, compact-valued, and continuous with respect to  ,

,

then  is an upper-semicontinuous correspondence. Moreover, if

is an upper-semicontinuous correspondence. Moreover, if  is unique, then it is a continuous of

is unique, then it is a continuous of  and

and  .[1]:156,506

.[1]:156,506

Combining with the previous subsection, if the consumer has strictly convex preferences, then the Marshallian demand is unique and continuous. In contrast, if the preferences are not convex, then the Marshallian demand may be non-unique and non-continuous.

Homogeneity

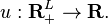

The Marshallian demand correspondence is a homogeneous function with degree 0. This means that for every constant  :

:

This is intuitively clear. Suppose  and

and  are measured in dollars. When

are measured in dollars. When  ,

,  and

and  are exactly the same quantities measured in cents. Obviously, changing the unit of measurement should not affect the demand.

are exactly the same quantities measured in cents. Obviously, changing the unit of measurement should not affect the demand.

Examples

In the following examples, there are two commodities, 1 and 2.

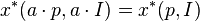

1. The utility function has the Cobb–Douglas form:

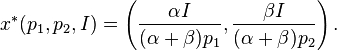

the constrained optimization leads to the Marshallian demand function:

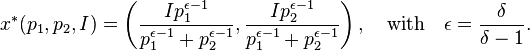

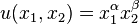

2. The utility function is a CES utility function:

then:

In both cases, the preferences are strictly convex, the demand is unique and the demand function is continuous.

3. The utility function has the linear form:

.

.

the utility function is only weakly convex, and indeed the demand is not unique: when  , the consumer may divide his income in arbitrary ratios between product types 1 and 2 and get the same utility.

, the consumer may divide his income in arbitrary ratios between product types 1 and 2 and get the same utility.

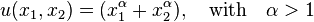

4. The utility function exhibits a non-diminishing marginal rate of substitution:

.

.

The utility function is concave, and indeed the demand is not continuous: when  , the consumer demands only product 1, and when

, the consumer demands only product 1, and when  , the consumer demands only product 2 (when

, the consumer demands only product 2 (when  the demand correspondence contains two distinct bundles: either buy only product 1 or buy only product 2).

the demand correspondence contains two distinct bundles: either buy only product 1 or buy only product 2).

See also

References

- Mas-Colell, Andreu; Whinston, Michael & Green, Jerry (1995). Microeconomic Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507340-1.

- Nicholson, Walter (1978). Microeconomic Theory (Second ed.). Hinsdale: Dryden Press. pp. 90–93. ISBN 0-03-020831-9.

- 1 2 Varian, Hal (1992). Microeconomic Analysis (Third ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 0393957357.

![u(x_1,x_2) = \left[ \frac{x_1^{\delta}}{\delta} + \frac{x_2^{\delta}}{\delta} \right]^{\frac{1}{\delta}}](../I/m/6e409e6e7bb03eb249005c57a67aaad4.png)