Walker and Williams in Dahomey

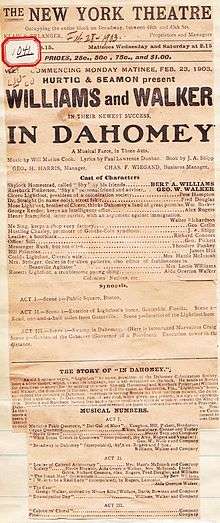

Walker and Williams In Dahomey (1903-1905) is a black musical written by Jesse A. Shipp as a satire on the American Colonization Society's back-to-Africa movement. Regarded as "the first full-length musical written and played by blacks to be performed at a major Broadway house”, In Dahomey is lauded as a marquee turning point for African American representation in vaudeville theater. It featured lyrics by poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, music by popular ragtime musician Will Marion Cook, and was produced by Harry Seamon and McVon Hurtig. The musical starred leading comedians George Walker and Bert Williams, two iconic figures of vaudeville entertainment at the time. In Dahomey opened in the New York Theater on February 18, 1903. The musical ran for 53 completed performances, including two tours in the United States and one tour of the United Kingdom.[2] In total, In Dahomey ran for a combined total of four years.[3]

Performance

As the first all-Black musical to be playing on Broadway, Walker and Williams In Dahomey received a remarkable amount of publicity after its initial opening on February 18, 1903. It was also the first American black musical to be performed abroad.[4]

Themes

Featuring the renowned comic pair of the lighter-skinned Bert Williams and George W. Walker, the show was the first to introduce a critical discourse of African Imperialism into the vaudeville theatre scene.[5] Walker and Williams were said to have emphasized some of the most important components of early 20th century Black musicals: fast-changing scenery using tableau (presumably painted backdrops), improvisation, traditional Black-facing, heavy pantomime, and interpolation of songs borrowed from other original source-texts.

Summary

In Dahomey follows the attempts of two con men (played by Bert Williams and George Walker) charged with recovering a lost heirloom to be flipped for profit. The search for the heirloom crosses paths with a colonized society that looks to settle in Dahomey.

The plot of the original source-text differs according to many sources, but all agree there were three primary locales in In Dahomey: Boston, Gatorville (Florida) and Dahomey. A recovered New York Theatre program printed a synopsis in February, 1903 generally concurs with the scenes depicted in extant scripts. The recovered synopsis reads:

An old Southern negro, Lightfoot by name, president of the Dahomey Colonization Society, loses a silver casket, which, to use his language, has a cat scratched on its back. He sends to Boston for detectives to search for the missing treasure. Shylock Homestead and Rareback Pinkerton (Williams and Walker), the detectives in the case, failing to find the casket at Gatorville, Florida, Lightfoot’s home, accompany the colonists to Dahomey. Previous to leaving Boston on their perilous mission, the detectives join a syndicate. In Dahomey, rum of any kind, when given as a present, is a sign of appreciation. Shylock and Rareback, having free access to the syndicate’s stock of whiskey, present the King of Dahomey with three barrels of appreciation and in return are made Caboceers (Governors of a Province). In the meantime, the colonists, having had a misunderstanding with the King, are made prisoners. Prisoners and criminals are executed on festival days, known in Dahomey as Customs Day. The new Caboceers, after supplying the King with his third barrel of appreciation )whiskey), secure his consent to liberate the collagists after which an honor is conferred on Rareback and Shylock, which causes them to decide “There’s No Place Like Home.”[6]

Music

In Dahomey captures much of the perspective of early 20th century Broadway. Many songs heavily feature classic vaudevillian extractability and dramatic flexibility. Fewer than a half dozen songs were topically linear to In Dahomey’s driving narrative. Only two songs, “My Dahomian Queen” and “On Broadway in Dahomey Bye and Bye” reference location and plot integration. Many of In Dahomey’s songs, such as “Brown-Skin Baby Mine,” “My Castle on the Nile,”, “Evah Dahkey Is a King,” “When It’s All Goin’ Out and Nothin’ Comin In,” “Good Evenin’,” have been performed in other vaudevillian Broadway shows.[7]

Musical Numbers

| Musical Number Title | Music and Lyrics | Performer |

|---|---|---|

| "Dat Gal of Mine" | Benjamin L. Shook | Male Quartet |

| "Organ Quartette" | Unknown | Colonist |

| "Molly Green" | Will Marion Cook, Cecil Mack | Company |

| "When Sousa Comes to Coontown" | James Vaughn, Tom Lemonier, Alex Rogers | Rareback Pinkerton, Company |

| "(On) Broadway in Dahomey (Bye and Bye) | Al Johns, Alex Rogers | Shylock, Rareback Pinkerton, Company |

| "Leader of the Colored Aristocracy" | James Weldon Johnson | Cecillia, Company |

| "Society" | Will Marion Cook, Will Accooe | Chorus |

| "The Jonah Man" | Alex Rogers | Shylock |

| "I Want To Be A Real Lady" | Tom Lemonier, Alex Rogers | Rosetta |

| "The Czar" | John H. Cook, Will Marion Cook, Alex Rogers | Rareback Pinkerton, Company (female) |

| "(On) Emancipation Day" | Unknown | Shylock, Rareback Pinkerton, Company |

| "Caboceers Choral" | Unknown | Company |

| "Finale" | Unknown | Company |

Original Cast

| Characters | Players |

|---|---|

| Shylock Homestead, called “Shy” by his friends | Bert A. Williams |

| Rareback Pinkerton, “Shy’s” personal friend and advisor | George W. Walker |

| Cicero Lightfoot, president of the colonization society | Pete Hampton |

| Dr. Straight (in name only), street fakir | Fred Douglas |

| Mose Lightfoot, brother of Cicero | Pete Hampton |

| George Reeder, keeps an intelligence office | Alex Rogers |

| Henry Stampfield, letter carrier | Walter Richardson |

| Me Sing, keeps a chop suey factory | Geo Catlin |

| Hustling Charley, promotor of Got-the-Coin syndicate | J.A. Shipp |

In its entirety, In Dahomey featured plenty more secondary characters than its opening stage at the Harry de Jur theatre could comfortably hold.[9]

Later works

Walker and Williams would go on to produce two more musicals as the same act, Williams and Walker In Abyssinia and Walker and Williams in Bandana Land, with different themes, staging and locales.[10]

References

- ↑ Obrecht, Jas. "Jas Obrecht Music Archive." Jas Obrecht Music Archive. N.p., 11 Aug. 2011. Web

- ↑ Riis, Thomas L., Just Before Jazz: Black Musical Theater in New York, 1890-1915 (London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989), p. 91

- ↑ Hatch, James. V. Black Theatre USA (New York: The Free Press, 1996), pp. 64-65

- ↑ Southern, Eileen (1997). The Music of Black Americans: A History. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 222. ISBN 0393038432.

- ↑ Graziano, John, "In Dahomey", in Black Theatre: U.S.A. (New York: The Free Press, 1996)

- ↑ Riis, Thomas L. The Music and Scripts of In Dahomey. Madison: A-R Ed., 1996. Print.

- ↑ Riis, Thomas L. The Music and Scripts of In Dahomey. Madison: A-R Ed., 1996. Print.

- ↑ "In Dahomey." In Dahomey. Guide To Musical Theater, n.d. Web. <http://www.guidetomusicaltheatre.com/shows_i/InDahomey.html>

- ↑ "In Dahomey." In Dahomey. Guide To Musical Theater, n.d. Web. <http://www.guidetomusicaltheatre.com/shows_i/InDahomey.html>

- ↑ Southern, Eileen (1997). The Music of Black Americans: A History. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 222. ISBN 0393038432.

External links

- Jones, Kenneth. "First Legit African-American Musical, In Dahomey, Inspires New Version in NYC June 23-July 25." Playbill. Playbill, 22 June 1999

- "In Dahomey." In Dahomey. Guide To Musical Theater