Wafer tumbler lock

A wafer tumbler lock is a type of lock that uses a set of flat wafers to prevent the lock from opening unless the correct key is inserted. This type of lock is similar to the pin tumbler lock and works on a similar principle. However, unlike the pin tumbler lock, where each pin consists of two or more pieces, each wafer in the lock is a single piece. The wafer tumbler lock is often incorrectly referred to as a disc tumbler lock, which uses an entirely different mechanism.

Early development

The earliest record of the wafer tumbler lock in the United States is the patent in 1868 by Philo Felter. Manufactured in Cazenovia, New York, it used a flat double-bitted key. Felter's lock was patented only three years after Linus Yale, Jr. received a patent for his revolutionary pin tumbler mortise lock, considered to be the first pin tumbler lock of the modern era. That lock featured a flat steel key, referred to as a "feather key" because of the marked contrast with the heavy bit keys of the day. Just two years later, Hiram S. Shepardson produced a different type of wafer tumbler lock, which used a single-bitted flat steel key, similar to Yale's feather key.[1]

By 1878, Yale Lock had purchased Shepardson's company, The United States Lock Company, as well as Felter's American Lock Manufacturing Company.[2] For the next 35 years, production of wafer tumbler locks languished in the U. S. And while Felter and Shepardson had designed their wafer tumbler locks for a variety of applications such as drawer and desk locks as well as padlocks and door locks, the wafer tumbler locks made during this era were mainly used for doors in mortise locks and night-latches.

Emil Christoph developed a wafer tumbler lock in 1913 which used a double-bitted key. His patent was assigned to King Lock of Chicago, a new lock manufacturer. By 1915 Briggs & Stratton Corporation was using King wafer tumbler locks in their ignition switches. In 1919, Briggs & Stratton applied for a switch patent using a wafer tumbler lock of their own design, which used a double-bitted key. Five years later, Edward N. Jacobi of Briggs & Stratton filed for a patent for a five-wafer, single-bitted wafer tumbler lock. The first recorded use of this lock was for an automobile, the 1924 Hupp Eight.

Design

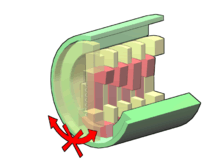

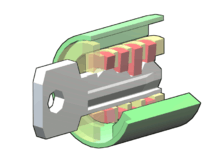

In a cylindrical wafer tumbler lock, a series of flat wafers holds a cylindrical plug in place. The wafers are fitted into vertical slots in the plug, and are spring-loaded, causing them to protrude into diametrically opposed wide grooves in the outer casing of the lock. As long as any of the wafers protrude into one of the wide grooves, rotation of the plug is blocked, as would be the case if there was no key, or if an improperly bitted key were inserted.

A rectangular hole is cut into the center of each wafer; the vertical position of the holes in the wafers vary, so a key must have notches corresponding to the height of the hole in each wafer, so that each wafer is pulled in to the point where the wafer edges are flush with the plug, clearing the way for the plug to rotate in order to open the lock. If any wafer is insufficiently raised, or raised too high, the wafer edge will be in one of the grooves, blocking rotation.

Types and wafer arrangements

Wafer tumbler lock configurations vary with manufacturer. The most common is the single-bitted, five-wafer configuration most commonly found on desk and cabinet locks and some key switches.

Some wafer tumbler locks use a stack of closely spaced wafers designed to fit a specific contour of a double-sided key and work on the principle of a carpenter's contour gauge.

Wafer tumbler locks can use single-bitted or double-bitted keys. Though wafer arrangements within the plug may vary, such as automotive locks, where the wafers are arranged in opposed sets, requiring a double-bitted key, the operating principle remains the same.

Crushable wafer tumbler lock

At one time, several manufacturers made a "crushable wafer tumbler"[3] for these locks, the idea being to simplify the task of rekeying for locksmiths and reduce the number of different wafers that needed to be manufactured and stocked. To rekey such a lock, the locksmith simply replaced all the wafers with identical "crushable wafers", cut the new key, inserted the key into the plug, inserted the plug into a special "crushing" tool, and squeezed the handle of the tool, crushing the wafers to fit the key. It was quick and easy but had reliability problems: debris from the crushed wafers often remained in the plug causing wear and occasional jamming of wafers or the plug, and sometimes wafers crushed unevenly making them weak and causing them to break later in use. This system was eventually abandoned.

References

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||