Waardenburg syndrome

| Waardenburg syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | E70.3 (ILDS E70.32) |

| ICD-9-CM | 270.2 |

| DiseasesDB | 14021 33475 |

| MedlinePlus | 001428 |

| eMedicine | ped/2422 derm/690 |

| MeSH | D014849 |

Waardenburg syndrome (also Waardenburg Shah Syndrome, Waardenburg-Klein syndrome) is a rare genetic disorder most often characterized by varying degrees of deafness, minor defects in structures arising from the neural crest, and pigmentation anomalies.

It was first described in 1951.[1]

Eponyms and classification

Waardenburg syndrome is named after Dutch ophthalmologist Petrus Johannes Waardenburg (1886–1979), who described the syndrome in detail in 1951.[1][2] The condition he described is now categorized as WS1. Swiss ophthalmologist David Klein also made contributions towards the understanding of the syndrome.[3]

WS2 was identified in 1971, to describe cases where dystopia canthorum did not present.[4] WS2 is now split into subtypes, based upon the gene responsible.

Other types have been identified, but they are less common.

Mutations in the EDN3, EDNRB, MITF, PAX3, SNAI2, and SOX10 genes are implicated in Waardenburg Syndrome. Some of these genes are involved in the making of melanocytes, which makes the pigment melanin. Melanin is an important pigment in the development of hair, eye color, skin, and functions of the inner ear. So the mutation of these genes can lead to abnormal pigmentation and hearing loss.[5] PAX3 and MTIF gene mutation occurs in type I and II (WS1 and WS2). Type III (WS3) shows mutations of the PAX3 gene also. SOX10, EDN3, or EDNRB gene mutations occur in type IV. Type IV (WS4) can also affect portions of nerve cell development that potentially can lead to intestinal issues.

Signs and symptoms

.jpg)

Symptoms vary from one type of the syndrome to another and from one patient to another, but they include:

- Very pale or brilliantly blue eyes, eyes of two different colors (complete heterochromia), or eyes with one iris having two different colours (sectoral heterochromia);[6]

- A forelock of white hair (poliosis), or premature graying of the hair;[7][6]

- Appearance of wide-set eyes due to a prominent, broad nasal root (dystopia canthorum)—particularly associated with type I) also known as telecanthus;

- Moderate to profound hearing loss (higher frequency associated with type II);[6]

- A low hairline and eyebrows that touch in the middle (synophrys).

- Patches of white pigmentation on the skin have been observed in some people. Sometimes, abnormalities of the arms, associated with type III, have been observed.

- Type IV may include neurologic manifestations.

Waardenburg syndrome has also been associated with a variety of other congenital disorders, such as intestinal and spinal defects, elevation of the scapula, and cleft lip and palate. Sometimes this is concurrent with Hirschsprung disease.

Classification

Subtypes of the syndrome are traceable to different genetic variations and presentations:

| Type | OMIM | Gene | Locus | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I, WS1 | 193500 | PAX3 | 2q35 | |

| Type IIa, WS2A (originally WS2) | 193510 | MITF | 3p14.1-p12.3 | |

| Type IIb, WS2B | 600193 | WS2B | 1p21-p13.3 | |

| Type IIc, WS2C | 606662 | WS2C | 8p23 | |

| Type IId, WS2D (very rare) | 608890 | SNAI2 | 8q11 | |

| Type III, WS3 | 148820 | PAX3 | 2q35 | |

| Type IVa, WS4A | 277580 | EDNRB | 13q22 | Characteristics of Waardenburg syndrome, in addition to Hirschsprung disease which can be life-threatening and requires surgery if the colon is enlarged.[6][8] |

| Type IVb, WS4B | 613265 | EDN3 | 20q13 | |

| Type IVc, WS4C | 613266 | SOX10 | 22q13 |

Type III is also known as Klein-Waardenburg syndrome, and type IV is also known as Waardenburg-Shah syndrome.[6]

Epidemiology

The overall incidence is ~1/42,000 to 1/50,000 people. Types I and II are the most common types of the syndrome, whereas types III and IV are rare. Type 4 is also known as Waardenburg‐Shah syndrome (association of Waardenburg syndrome with Hirschsprung disease).

Type 4 is rare with only 48 cases reported up to 2002.[9]

About 1 in 30 students in schools for the deaf have Waardenburg syndrome. All races and sexes are affected equally. The highly variable presentation of the syndrome makes it difficult to arrive at precise figures for its prevalence.

Inheritance

This condition is usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene is sufficient to cause the disorder. In most cases, an affected person has one parent with the condition. A small percentage of cases result from new mutations in the gene; these cases occur in people with no history of the disorder in their family.

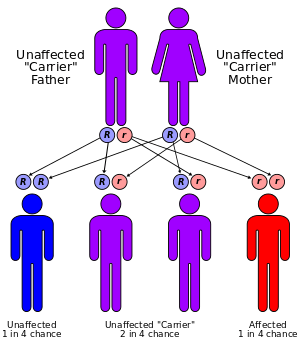

Some cases of type II and type IV Waardenburg syndrome appear to have an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, which means two copies of the gene must be altered for a person to be affected by the disorder. Most often, the parents of a child with an autosomal recessive disorder are not affected but are carriers of one copy of the altered gene.

-

Waardenburg syndrome is usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

-

Types II and IV Waardenburg syndrome may sometimes have an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance.

Types I and III inheritance of this trait is autosomal dominant. If an affected parent is homozygous dominant there is a 100% that the child will be affected and if the affected parent is heterozygous dominant then there is a 50% chance that a child of an affected parent will be affected. Symptoms vary and so the extremity of symptoms cannot be determined. Types II and IV is autosomal recessive, symptoms are not definite they vary just as the other type’s symptoms will. A study was done on a rare case of a double heterozygous child with each parent having only single mutations in MTIF or PAX3. The effect of double heterozygous mutations in the genes MTIF and PAX3 in WS1 and WS2 can increase the pigment-affected symptoms. It leads to the conclusion that the double mutation of MTIF is associated with the extremity of Waardenburg Syndrome and may affect the phenotypes or symptoms of the syndrome [10]

Treatment

There is currently no treatment or cure for Waardenburg syndrome. The symptom most likely to be of practical importance is deafness, and this is treated as any other irreversible deafness would be. In marked cases there may be cosmetic issues. Other abnormalities (neurological, structural, Hirschsprung disease) associated with the syndrome are treated symptomatically.

In animals

Waardenburg syndrome is known to occur in ferrets. The affected individual will usually have a small white stripe along the top or back of the head and sometimes down the back of the neck (this is known as a "blaze" coat pattern), or a solid white head from nose to shoulders (known as a "panda" coat pattern). The ferret will often have a very slightly flatter skull than ferrets without the syndrome and may have unusually wide-set eyes. As a ferret's sense of hearing is poor to begin with, associated deafness is not easily noticeable except for a lack of reaction to loud noises. As the disorder is easily spread to offspring, the affected animal will not be used for breeding by private, reputable breeders, although it may still be neutered and sold as a pet. However, largely as a result of mass-breeding due to the "exotic" markings it gives, 75% of US ferrets with a blaze or white head sold from pet stores are deaf.[11]

Domesticated cats with blue eyes and white coats are often completely deaf.[12] Whether or not this is a result of Waardenburg syndrome remains unclear.[13] Deafness is far more common in white cats than in those with other coat colors. According to the ASPCA Complete Guide to Cats, "17 to 20 percent of white cats with nonblue eyes are deaf; 40 percent of "odd-eyed" white cats with one blue eye are deaf; and 65 to 85 percent of blue-eyed white cats are deaf."[14] In the 1980s, college genetic classes taught that the genes for deafness and white coat color were closely linked, resulting in the majority of cats with completely white coats and bluer eyes being deaf.[15] The newer evidence cited above refutes this simplistic idea.

In popular culture

In the season 6 episode of Bones, 'The Signs in the Silence', the team must solve a case in which the suspected killer has Waardenburg syndrome.

Enzo Macleod, protagonist of Peter May's series The Enzo Files, has Waardenburg syndrome. His eyes are different colors and he has a white streak in his hair. See pp. 17–18 of Extraordinary People (2006) by Peter May.

The book Reconstructing Amelia by Kimberly McCreight features several characters with Waardenburg symptoms.

The book Closer Than You Think by Karen Rose features three characters, siblings, with Waardenburg Syndrome.

Other contributors

- Waardenburg-Klein syndrome is named after Petrus Johannes Waardenburg (1886–1979), a Dutch ophthalmologist and geneticist, and David Klein, a Swiss human geneticist and ophthalmologist.

- Mende's syndrome II is named after Irmgard Mende (1938–), a German-American physician.

- Van der Hoeve-Halbertsma-Waardenburg Syndrome is named after Jan Van der Hoeve (1878–1952), a Dutch ophthalmologist, Nicolaas Adolf Halbertsma (1889–1968), Dutch physician and Petrus Johannes Waardenburg (1886–1979).

- Van der Hoeve-Halbertsma-Gualdi syndrome is named for Jan Van der Hoeve (1878–1952), Nicolaas Adolf Halbertsma (1889–1968) and Vincenzo Gualdi (1891–1976), an Italian physician.

- Vogt’s syndrome is named for Cecile Vogt (1875–1962), a French-German neuropathologist.

See also

References

- 1 2 Waardenburg PJ (September 1951). "A New Syndrome Combining Developmental Anomalies of the Eyelids, Eyebrows and Noseroot with Pigmentary Anomalies of the Iris and Head Hair and with Congenital Deafness; Dystopia canthi medialis et punctorum lacrimalium lateroversa, Hyperplasia supercilii medialis et radicis nasi, Heterochromia iridum totalis sive partialis, Albinismus circumscriptus (leucismus, poliosis) et Surditas congenita (surdimutitas)". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 3 (3): 195–253. PMC 1716407. PMID 14902764.

- ↑ Petrus Johannes Waardenburg at Who Named It?

- ↑ Klein-Waardenburg syndrome at Who Named It?

- ↑ Arias S (1971). "Genetic Heterogeneity in the Waardenburg Syndrome". Birth Defects Original Article Series 7 (4): 87–101. PMID 5006208.

- ↑ Kumar, Sudesh, and Kiran Rao. "Waardenburg Syndrome: A Rare Genetic Disorder, A Report of Two Cases." Indian Journal of Human Genetics 18.2 (2012): 254-255. Academic Search Premier. Web. 4 Apr. 2014.,

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Waardenburg syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Reviewed October 2012. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Premature Graying Of Hair".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baral, Viviane, et al. “Screening of MTIF and SOX10 Regulatory Regions In Waardenburg Syndrome Type 2. “Plos ONE 7.7 (2012): 1-8. Academic Search Premier. Web. 4 Apr. 2014.

- ↑ Egbalian F (2008). "Waardenburg-Shah Syndrome; A Case Report and Review of the Literature" (PDF). Iranian Journal of Pediatrics 18 (1): 71–74.

- ↑ Yang, T, et al. “Double Heterozygous Mutations Of MTIF and PAX3 Result in Waardenburg Syndrome With Increased Penetrance In Pigmentary defects.” Clinical Genetics 83.1 (2013): 78-62. Academic Search Premier. Web. 3 Apr. 2014.

- ↑ Matulich E. "Deafness in Ferrets". Cypresskeep.com.

- ↑ Webb AA, Cullen CC (2010). "Coat color and coat color pattern-related neurologic and neuro-ophthalmic diseases" (PDF). The Canadian Veterinary Journal 51 (6): 653–657. PMC 2871368. PMID 20808581.

- ↑ Geigy CA, Heid S, Steffen F, Danielson K, Jaggy A, Gaillard C (2007). "Does a pleiotropic gene explain deafness and blue irises in white cats?". Veterinary Journal 173 (3): 548–553. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.07.021. PMID 16956778.

- ↑ Richards J (1999). ASPCA Complete Guide to Cats: Everything You Need to Know About Choosing and Caring for Your Pet. Chronicle Books. p. 71. ISBN 9780811819299.

- ↑ DeeAnn Williams Visk, personal recollection.

External links

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Waardenburg Syndrome Type I

- OMIM Genetic disorder catalog — Waardenburg syndrome

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||