Weak interaction

| Standard Model of particle physics |

|---|

Large Hadron Collider tunnel at CERN |

|

Constituents |

|

Limitations |

|

Scientists Rutherford · Thomson · Chadwick · Bose · Sudarshan · Koshiba · Davis, Jr. · Anderson · Fermi · Dirac · Feynman · Rubbia · Gell-Mann · Kendall · Taylor · Friedman · Powell · P. W. Anderson · Glashow · Meer · Cowan · Nambu · Chamberlain · Cabibbo · Schwartz · Perl · Majorana · Weinberg · Lee · Ward · Salam · Kobayashi · Maskawa · Yang · Yukawa · 't Hooft · Veltman · Gross · Politzer · Wilczek · Cronin · Fitch · Vleck · Higgs · Englert · Brout · Hagen · Guralnik · Kibble · Ting · Richter |

In particle physics, the weak interaction is the mechanism responsible for the weak force or weak nuclear force, one of the four known fundamental interactions of nature, alongside the strong interaction, electromagnetism, and gravitation. The weak interaction is responsible for the radioactive decay of subatomic particles, and it plays an essential role in nuclear fission. The theory of the weak interaction is sometimes called quantum flavordynamics (QFD), in analogy with the terms QCD and QED, but the term is rarely used because the weak force is best understood in terms of electro-weak theory (EWT).[1]

In the Standard Model of particle physics, the weak interaction is caused by the emission or absorption of W and Z bosons. All known fermions interact through the weak interaction. Fermions are particles that have half-integer spin (one of the fundamental properties of particles). A fermion can be an elementary particle, such as the electron, or it can be a composite particle, such as the proton. The masses of W+, W−, and Z bosons are each far greater than that of protons or neutrons, consistent with the short range of the weak force. The force is termed weak because its field strength over a given distance is typically several orders of magnitude less than that of the strong nuclear force and electromagnetic force.

During the quark epoch, the electroweak force split into the electromagnetic and weak forces. Important examples of weak interaction include beta decay, and the production, from hydrogen, of deuterium needed to power the sun's thermonuclear process. Most fermions will decay by a weak interaction over time. Such decay also makes radiocarbon dating possible, as carbon-14 decays through the weak interaction to nitrogen-14. It can also create radioluminescence, commonly used in tritium illumination, and in the related field of betavoltaics.[2]

Quarks, which make up composite particles like neutrons and protons, come in six "flavours" – up, down, strange, charm, top and bottom – which give those composite particles their properties. The weak interaction is unique in that it allows for quarks to swap their flavour for another. For example, during beta minus decay, a down quark decays into an up quark, converting a neutron to a proton. Also the weak interaction is the only fundamental interaction that breaks parity-symmetry, and similarly, the only one to break CP-symmetry.

History

In 1933, Enrico Fermi proposed the first theory of the weak interaction, known as Fermi's interaction. He suggested that beta decay could be explained by a four-fermion interaction, involving a contact force with no range.[3][4]

However, it is better described as a non-contact force field having a finite range, albeit very short. In 1968, Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg unified the electromagnetic force and the weak interaction by showing them to be two aspects of a single force, now termed the electro-weak force.

The existence of the W and Z bosons was not directly confirmed until 1983.

Properties

.svg.png)

The weak interaction is unique in a number of respects:

- It is the only interaction capable of changing the flavor of quarks (i.e., of changing one type of quark into another).

- It is the only interaction that violates P or parity-symmetry. It is also the only one that violates CP symmetry.

- It is propagated by carrier particles (known as gauge bosons) that have significant masses, an unusual feature which is explained in the Standard Model by the Higgs mechanism.

Due to their large mass (approximately 90 GeV/c2[5]) these carrier particles, termed the W and Z bosons, are short-lived: they have a lifetime of under 1×10−24 seconds.[6] The weak interaction has a coupling constant (an indicator of interaction strength) of between 10−7 and 10−6, compared to the strong interaction's coupling constant of about 1 and the electromagnetic coupling constant of about 10−2;[7] consequently the weak interaction is weak in terms of strength.[8] The weak interaction has a very short range (around 10−17–10−16 m[8]).[7] At distances around 10−18 meters, the weak interaction has a strength of a similar magnitude to the electromagnetic force, but this starts to decrease exponentially with increasing distance. At distances of around 3×10−17 m, the weak interaction is 10,000 times weaker than the electromagnetic.[9]

The weak interaction affects all the fermions of the Standard Model, as well as the Higgs boson; neutrinos interact through gravity and the weak interaction only, and neutrinos were the original reason for the name weak force.[8] The weak interaction does not produce bound states (nor does it involve binding energy) – something that gravity does on an astronomical scale, that the electromagnetic force does at the atomic level, and that the strong nuclear force does inside nuclei.[10]

Its most noticeable effect is due to its first unique feature: flavor changing. A neutron, for example, is heavier than a proton (its sister nucleon), but it cannot decay into a proton without changing the flavor (type) of one of its two down quarks to up. Neither the strong interaction nor electromagnetism permit flavour changing, so this must proceed by weak decay; without weak decay, quark properties such as strangeness and charm (associated with the quarks of the same name) would also be conserved across all interactions. All mesons are unstable because of weak decay.[11] In the process known as beta decay, a down quark in the neutron can change into an up quark by emitting a virtual W− boson which is then converted into an electron and an electron antineutrino.[12] Another example is the electron capture, a common variant of radioactive decay, where a proton (up quark) and an electron within an atom interact, and are changed to a neutron (down quark) and an electron neutrino.

Due to the large mass of a boson, weak decay is much more unlikely than strong or electromagnetic decay, and hence occurs less rapidly. For example, a neutral pion (which decays electromagnetically) has a life of about 10−16 seconds, while a charged pion (which decays through the weak interaction) lives about 10−8 seconds, a hundred million times longer.[13] In contrast, a free neutron (which also decays through the weak interaction) lives about 15 minutes.[12]

Weak isospin and weak hypercharge

| Generation 1 | Generation 2 | Generation 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermion | Symbol | Weak isospin |

Fermion | Symbol | Weak isospin |

Fermion | Symbol | Weak isospin |

| Electron |  |

|

Muon |  |

|

Tau |  |

|

| Electron neutrino |  |

|

Muon neutrino |  |

|

Tau neutrino |  |

|

| Up quark |  |

|

Charm quark |  |

|

Top quark |  |

|

| Down quark |  |

|

Strange quark |  |

|

Bottom quark |  |

|

| All left-handed antiparticles have weak isospin of 0. Right-handed antiparticles have the opposite weak isospin. | ||||||||

All particles have a property called weak isospin (T3), which serves as a quantum number and governs how that particle interacts in the weak interaction. Weak isospin therefore plays the same role in the weak interaction as electric charge does in electromagnetism, and color charge in the strong interaction. All fermions have a weak isospin value of either +1⁄2 or −1⁄2. For example, the up quark has a T3 of +1⁄2 and the down quark −1⁄2. A quark never decays through the weak interaction into a quark of the same T3: quarks with a T3 of +1⁄2 decay into quarks with a T3 of −1⁄2 and vice versa.

In any given interaction, weak isospin is conserved: the sum of the weak isospin numbers of the particles entering the interaction equals the sum of the weak isospin numbers of the particles exiting that interaction. For example, a (left-handed) π+, with a weak isospin of 1 normally decays into a ν

μ (+1/2) and a μ+ (as a right-handed antiparticle, +1/2).[13]

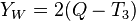

Following the development of the electroweak theory, another property, weak hypercharge, was developed. It is dependent on a particle's electrical charge and weak isospin, and is defined as:

where YW is the weak hypercharge of a given type of particle, Q is its electrical charge (in elementary charge units) and T3 is its weak isospin. Whereas some particles have a weak isospin of zero, all particles, except gluons, have non-zero weak hypercharge. Weak hypercharge is the generator of the U(1) component of the electroweak gauge group.

Interaction types

There are two types of weak interaction (called vertices). The first type is called the "charged-current interaction" because it is mediated by particles that carry an electric charge (the W+ or W− bosons), and is responsible for the beta decay phenomenon. The second type is called the "neutral-current interaction" because it is mediated by a neutral particle, the Z boson.

Charged-current interaction

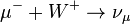

In one type of charged current interaction, a charged lepton (such as an electron or a muon, having a charge of −1) can absorb a W+ boson (a particle with a charge of +1) and be thereby converted into a corresponding neutrino (with a charge of 0), where the type ("flavour") of neutrino (electron, muon or tau) is the same as the type of lepton in the interaction, for example:

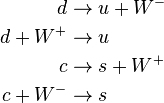

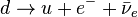

Similarly, a down-type quark (d with a charge of −1⁄3) can be converted into an up-type quark (u, with a charge of +2⁄3), by emitting a W− boson or by absorbing a W+ boson. More precisely, the down-type quark becomes a quantum superposition of up-type quarks: that is to say, it has a possibility of becoming any one of the three up-type quarks, with the probabilities given in the CKM matrix tables. Conversely, an up-type quark can emit a W+ boson – or absorb a W− boson – and thereby be converted into a down-type quark, for example:

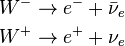

The W boson is unstable so will rapidly decay, with a very short lifetime. For example:

Decay of the W boson to other products can happen, with varying probabilities.[15]

In the so-called beta decay of a neutron (see picture, above), a down quark within the neutron emits a virtual W− boson and is thereby converted into an up quark, converting the neutron into a proton. Because of the energy involved in the process (i.e., the mass difference between the down quark and the up quark), the W− boson can only be converted into an electron and an electron-antineutrino.[16] At the quark level, the process can be represented as:

Neutral-current interaction

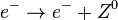

In neutral current interactions, a quark or a lepton (e.g., an electron or a muon) emits or absorbs a neutral Z boson. For example:

Like the W boson, the Z boson also decays rapidly,[15] for example:

Electroweak theory

The Standard Model of particle physics describes the electromagnetic interaction and the weak interaction as two different aspects of a single electroweak interaction, the theory of which was developed around 1968 by Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg. They were awarded the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work.[17] The Higgs mechanism provides an explanation for the presence of three massive gauge bosons (the three carriers of the weak interaction) and the massless photon of the electromagnetic interaction.[18]

According to the electroweak theory, at very high energies, the universe has four massless gauge boson fields similar to the photon and a complex scalar Higgs field doublet. However, at low energies, gauge symmetry is spontaneously broken down to the U(1) symmetry of electromagnetism (one of the Higgs fields acquires a vacuum expectation value). This symmetry breaking would produce three massless bosons, but they become integrated by three photon-like fields (through the Higgs mechanism) giving them mass. These three fields become the W+, W− and Z bosons of the weak interaction, while the fourth gauge field, which remains massless, is the photon of electromagnetism.[18]

This theory has made a number of predictions, including a prediction of the masses of the Z and W bosons before their discovery. On 4 July 2012, the CMS and the ATLAS experimental teams at the Large Hadron Collider independently announced that they had confirmed the formal discovery of a previously unknown boson of mass between 125–127 GeV/c2, whose behaviour so far was "consistent with" a Higgs boson, while adding a cautious note that further data and analysis were needed before positively identifying the new boson as being a Higgs boson of some type. By 14 March 2013, the Higgs boson was tentatively confirmed to exist .[19]

Violation of symmetry

The laws of nature were long thought to remain the same under mirror reflection, the reversal of one spatial axis. The results of an experiment viewed via a mirror were expected to be identical to the results of a mirror-reflected copy of the experimental apparatus. This so-called law of parity conservation was known to be respected by classical gravitation, electromagnetism and the strong interaction; it was assumed to be a universal law.[20] However, in the mid-1950s Chen Ning Yang and Tsung-Dao Lee suggested that the weak interaction might violate this law. Chien Shiung Wu and collaborators in 1957 discovered that the weak interaction violates parity, earning Yang and Lee the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics.[21]

Although the weak interaction used to be described by Fermi's theory, the discovery of parity violation and renormalization theory suggested that a new approach was needed. In 1957, Robert Marshak and George Sudarshan and, somewhat later, Richard Feynman and Murray Gell-Mann proposed a V−A (vector minus axial vector or left-handed) Lagrangian for weak interactions. In this theory, the weak interaction acts only on left-handed particles (and right-handed antiparticles). Since the mirror reflection of a left-handed particle is right-handed, this explains the maximal violation of parity. Interestingly, the V−A theory was developed before the discovery of the Z boson, so it did not include the right-handed fields that enter in the neutral current interaction.

However, this theory allowed a compound symmetry CP to be conserved. CP combines parity P (switching left to right) with charge conjugation C (switching particles with antiparticles). Physicists were again surprised when in 1964, James Cronin and Val Fitch provided clear evidence in kaon decays that CP symmetry could be broken too, winning them the 1980 Nobel Prize in Physics.[22] In 1973, Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa showed that CP violation in the weak interaction required more than two generations of particles,[23] effectively predicting the existence of a then unknown third generation. This discovery earned them half of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physics.[24] Unlike parity violation, CP violation occurs in only a small number of instances, but remains widely held as an answer to the difference between the amount of matter and antimatter in the universe; it thus forms one of Andrei Sakharov's three conditions for baryogenesis.[25]

See also

- Weakless Universe – the postulate that weak interactions are not anthropically necessary

- Gravity

- Nuclear force

- Electromagnetism

References

Citations

- ↑ Griffiths, David (2009). Introduction to Elementary Particles. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-3-527-40601-2.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1979: Press Release". NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Fermi, Enrico (1934). "Versuch einer Theorie der β-Strahlen. I". Zeitschrift für Physik A 88 (3–4): 161–177. Bibcode:1934ZPhy...88..161F. doi:10.1007/BF01351864.

- ↑ Wilson, Fred L. (December 1968). "Fermi's Theory of Beta Decay". American Journal of Physics 36 (12): 1150–1160. Bibcode:1968AmJPh..36.1150W. doi:10.1119/1.1974382.

- ↑ W.-M. Yao et al. (Particle Data Group) (2006). "Review of Particle Physics: Quarks" (PDF). Journal of Physics G 33: 1–1232. arXiv:astro-ph/0601168. Bibcode:2006JPhG...33....1Y. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/33/1/001.

- ↑ Peter Watkins (1986). Story of the W and Z. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-521-31875-4.

- 1 2 "Coupling Constants for the Fundamental Forces". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 J. Christman (2001). "The Weak Interaction" (PDF). Physnet. Michigan State University.

- ↑ "Electroweak". The Particle Adventure. Particle Data Group. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ↑ Walter Greiner; Berndt Müller (2009). Gauge Theory of Weak Interactions. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-540-87842-1.

- ↑ Cottingham & Greenwood (1986, 2001), p.29

- 1 2 Cottingham & Greenwood (1986, 2001), p.28

- 1 2 Cottingham & Greenwood (1986, 2001), p.30

- ↑ Baez, John C.; Huerta, John (2009). "The Algebra of Grand Unified Theories". Bull.Am.Math.Soc. 0904: 483–552. arXiv:0904.1556. Bibcode:2009arXiv0904.1556B. doi:10.1090/s0273-0979-10-01294-2. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- 1 2 K. Nakamura et al. (Particle Data Group) (2010). "Gauge and Higgs Bosons" (PDF). Journal of Physics G 37. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/37/7a/075021.

- ↑ K. Nakamura et al. (Particle Data Group) (2010). "n" (PDF). Journal of Physics G 37: 7. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/37/7a/075021.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1979". NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- 1 2 C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics – Higgs Bosons: Theory and Searches" (PDF). Physics Letters B 667: 1–6. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

- ↑ "New results indicate that new particle is a Higgs boson | CERN". Home.web.cern.ch. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Charles W. Carey (2006). "Lee, Tsung-Dao". American scientists. Facts on File Inc. p. 225. ISBN 9781438108070.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1957". NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1980". NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ M. Kobayashi, T. Maskawa (1973). "CP-Violation in the Renormalizable Theory of Weak Interaction". Progress of Theoretical Physics 49 (2): 652–657. Bibcode:1973PThPh..49..652K. doi:10.1143/PTP.49.652.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1980". NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Paul Langacker (2001) [1989]. "Cp Violation and Cosmology". In Cecilia Jarlskog. CP violation. London, River Edge: World Scientific Publishing Co. p. 552. ISBN 9789971505615.

General readers

- R. Oerter (2006). The Theory of Almost Everything: The Standard Model, the Unsung Triumph of Modern Physics. Plume. ISBN 978-0-13-236678-6.

- B.A. Schumm (2004). Deep Down Things: The Breathtaking Beauty of Particle Physics. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7971-X.

Texts

- D.A. Bromley (2000). Gauge Theory of Weak Interactions. Springer. ISBN 3-540-67672-4.

- G.D. Coughlan, J.E. Dodd, B.M. Gripaios (2006). The Ideas of Particle Physics: An Introduction for Scientists (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67775-2.

- W. N. Cottingham; D. A. Greenwood (2001) [1986]. An introduction to nuclear physics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-521-65733-4.

- D.J. Griffiths (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

- G.L. Kane (1987). Modern Elementary Particle Physics. Perseus Books. ISBN 0-201-11749-5.

- D.H. Perkins (2000). Introduction to High Energy Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62196-8.

| ||||||||||

|