W. G. Grace

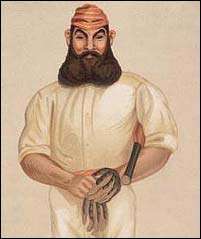

Portrait of Grace by Herbert Rose Barraud | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | William Gilbert Grace | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

18 July 1848 Downend, near Bristol, England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died |

23 October 1915 (aged 67) Mottingham, Kent, England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | W. G., The Doctor, The Champion, The Big 'Un, The Old Man, Mustafa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting style | right-handed batsman (RHB) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling style | right arm medium (RM; roundarm style) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | all-rounder | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relations | E. M. Grace, Fred Grace (brothers), Walter Gilbert (cousin) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 24) | 6 September 1880 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 1 June 1899 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1869–1904 | MCC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1870–1899 | Gloucestershire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1900–1904 | London County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Rae, pp.495–496 (CricketArchive): see also Footnote[a] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| part of a series of articles on W. G. Grace

|

|

Seasons |

| Career |

| Family E. M. Grace (brother) |

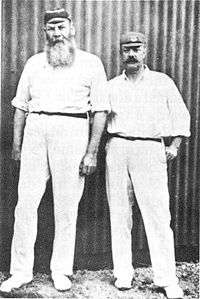

William Gilbert "W. G." Grace, MRCS, LRCP (18 July 1848 – 23 October 1915) was an English amateur cricketer who was important in the development of the sport and is widely considered one of its greatest-ever players. Universally known as "W. G.", he played first-class cricket for a record-equalling 44 seasons, from 1865 to 1908, during which he captained England, Gloucestershire, the Gentlemen, Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), the United South of England Eleven (USEE) and several other teams. He came from a cricketing family: the appearance in 1880 of W. G. with E. M. Grace, one of his elder brothers, and Fred Grace, his younger brother, was the first time three brothers played together in Test cricket.

Right-handed as both batsman and bowler, Grace dominated the sport during his career. His technical innovations and enormous influence left a lasting legacy. An outstanding all-rounder, he excelled at all the essential skills of batting, bowling and fielding, but it is for his batting that he is most renowned. He is held to have invented modern batsmanship. Usually opening the innings, he was particularly admired for his mastery of all strokes, and his level of expertise was said by contemporary reviewers to be unique. He generally captained the teams he played for at all levels because of his skill and tactical acumen.

Grace qualified as a medical practitioner in 1879. Because of his medical profession, he was nominally an amateur cricketer but he is said to have made more money from his cricketing activities than any professional cricketer. He was an extremely competitive player and, although he was one of the most famous men in England, he was also one of the most controversial on account of his gamesmanship and moneymaking.

He took part in other sports also: he was a champion 440-yard hurdler as a young man and also played football for the Wanderers. In later life, he developed enthusiasm for golf, lawn bowls and curling.

Early years

Childhood

W. G. Grace was born in Downend, near Bristol, on 18 July 1848 at his parents' home, Downend House, and was baptised at the local church on 8 August.[1] He was called Gilbert in the family circle, except by his mother who called him Willie,[1] but otherwise he was universally known by his initials W. G. His parents were Henry Mills Grace and Martha (née Pocock), who were married in Bristol on Thursday, 3 November 1831 and lived out their lives at Downend, where Henry Grace was the local GP.[2] Downend is near Mangotsfield and, although it is now a suburb of Bristol, it was then "a distinct village surrounded by countryside" and about four miles from Bristol.[3] Henry and Martha Grace had nine children in all: "the same number as Victoria and Albert – and in every respect they were the typical Victorian family".[4] Grace was the eighth child in the family; he had three older brothers, including E. M., and four older sisters. Only Fred, born in 1850, was younger than W. G.[5]

Grace began his Cricketing Reminiscences (1899) by answering a question he had frequently been asked: i.e., was he "born a cricketer"? His answer was in the negative because he believed that "cricketers are made by coaching and practice", though he adds that if he was not born a cricketer, he was born "in the atmosphere of cricket".[6] His father and mother were "full of enthusiasm for the game" and it was "a common theme of conversation at home".[7] In 1850, when W. G. was two and Fred was expected, the family moved to a nearby house called "The Chesnuts" which had a sizeable orchard and Henry Grace organised clearance of this to establish a practice pitch that was to become famous throughout the world of cricket.[8] All nine children in the Grace family, including the four daughters, were encouraged to play cricket although the girls, along with the dogs, were required for fielding only.[9] Grace claimed that he first handled a cricket bat at the age of two.[8] It was in the Downend orchard and as members of their local cricket clubs that he and his brothers developed their skills, mainly under the tutelage of his uncle, Alfred Pocock, who was an exceptional coach.[10] Apart from his cricket and his schooling, Grace lived the life of a country boy and roamed freely with the other village boys. One of his regular activities was stone throwing at birds in the fields and he later claimed that this was the source of his eventual skill as an outfielder.[11]

Education

Grace was "notoriously unscholarly".[12] His first schooling was with a Miss Trotman in Downend village and then with a Mr Curtis of Winterbourne.[12] He subsequently attended a day school called Ridgway House, run by a Mr Malpas, until he was fourteen. One of his schoolmasters, David Barnard, later married Grace's sister Alice.[12] In 1863, Grace was taken seriously ill with pneumonia and his father removed him from Ridgway House. After this illness, Grace grew rapidly to his full height of 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m).[13] He continued his education at home where one of his tutors was the Reverend John Dann, who was the Downend parish church curate; like Mr Barnard before him, Mr Dann became Grace's brother-in-law, marrying Blanche Grace in 1869.[14]

Grace never went to university as his father was intent upon him pursuing a medical career. But Grace was approached by both Oxford University Cricket Club and Cambridge University Cricket Club. In 1866, when he played a match at Oxford, one of the Oxford players, Edmund Carter, tried to interest him in becoming an undergraduate.[15] Then, in 1868, Grace received overtures from Caius College, Cambridge, which had a long medical tradition.[16] Grace said he would have gone to either Oxford or Cambridge if his father had allowed it.[16] Instead, he enrolled at Bristol Medical School in October 1868, when he was 20.[16]

Development as a cricketer

Henry Grace founded Mangotsfield Cricket Club in 1845 to represent several neighbouring villages including Downend.[8] In 1846, this club merged with the West Gloucestershire Cricket Club whose name was adopted until 1867.[10] It has been said that the Grace family ran the West Gloucestershire "almost as a private club".[10] Henry Grace managed to organise matches against Lansdown Cricket Club in Bath, which was the premier West Country club. West Gloucestershire fared poorly in these games and, sometime in the 1850s, Henry and Alfred Pocock decided to join Lansdown, although they continued to run the West Gloucestershire and this remained their primary club.[17]

Alfred Pocock was especially instrumental in coaching the Grace brothers and spent long hours with them on the practice pitch at Downend.[18] E. M., who was seven years older than W. G., had always played with a full size bat and so developed a tendency, that he never lost, to hit across the line, the bat being too big for him to "play straight". Pocock recognised this problem and determined that W. G. and his youngest brother Fred should not follow suit. He therefore fashioned smaller bats for them, to suit their sizes, and they were taught to play straight and "learn defence, with the left shoulder well forward", before attempting to hit.[18]

Grace recorded in his Reminiscences that he saw his first great cricket match in 1854 when he was barely six years old, the occasion being a game between William Clarke's All-England Eleven (the AEE) and twenty-two of West Gloucestershire. He says he himself played for the West Gloucestershire club as early as 1857, when he was nine years old, and had 11 innings in 1859.[19] The earliest match in CricketArchive which involved Grace was in 1859, only a few days after his eleventh birthday, when he played for Clifton Cricket Club against the South Wales Cricket Club at Durdham Down, his team winning by 114 runs. Several members of the Grace family, including his elder brother E. M., were involved in the match. Grace batted at number 11 and scored 0 and 0 not out.[20] The first time he made a substantial score was in July 1860 when he scored 51 for West Gloucestershire against Clifton; he wrote that none of his great innings gave him more pleasure.[19] It was through E. M. that the family name first became famous. His mother, Martha, wrote the following in a letter to William Clarke's successor George Parr in 1860 or 1861:[21]

I am writing to ask you to consider the inclusion of my son, E. M. Grace – a splendid hitter and most excellent catch – in your England XI. I am sure he would play very well and do the team much credit. It may interest you to learn that I have another son, now twelve years of age, who will in time be a much better player than his brother because his back stroke is sounder, and he always plays with a straight bat.

Grace was just short of his thirteenth birthday when, on 5 July 1861, he made his debut for Lansdown and played two matches that month.[17] E. M. had made his debut in 1857, aged sixteen.[17] In August 1862, aged 14, Grace played for West Gloucestershire against a Devonshire team.[22] A year later, following his bout of pneumonia which had left him bed-ridden for several weeks, he scored 52 not out and took 5 wickets against a Somerset XI.[22][23] Soon afterwards, he was one of four family members who played for Bristol and Didcot XVIII against the All-England Eleven.[24] He bowled well and scored 32 off the bowling of John Jackson, George Tarrant and Cris Tinley. E. M. took ten wickets in the match, which Bristol and Didcot won by an innings, and as a result E. M. was invited to tour Australia a few months later with George Parr's England team.[25]

E. M. did not return from Australia until July 1864 and his absence presented Grace with an opportunity to appear on cricket's greatest stages.[26] He and his elder brother Henry were invited to play for the South Wales Club which had arranged a series of matches in London and Sussex, though Grace wondered humorously how they were qualified to represent South Wales.[26] It was the first time that Grace left the West Country and he made his debut appearances at both The Oval and Lord's.[27]

Cricket career (1864 to 1914)

First-class career summary

The details of Grace's statistical first-class career are controversial but CricketArchive recognises 1865 to 1908 as its span and lists 29 teams, the England national team and 28 domestic teams, represented by Grace in first-class matches. Most of these were ad hoc or guest appearances. In minor cricket, Grace represented upwards of forty teams. Besides playing for England in Test cricket (1880–99), the key teams in Grace's first-class career were the Gentlemen (1865–1906), All-England aka England (i.e., non-international; 1865–99), Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC; 1869–1904), Gloucestershire (1870–99), the United South of England Eleven (USEE; 1870–76) and London County (1900–04). Apart from the London County venture in his later years, Grace had firmly committed himself to all of these by the end of the 1870 season when he was 22.[28][29]

Cricket in the 1860s underwent a revolution with the legalisation of overarm bowling in June 1864 and Grace himself said it was "no exaggeration to say that, between 1860 and 1870, English cricket passed through its most critical period" with the game in transition and "it was quite a revolutionary period so far as its rules were concerned".[30] Grace was still 15 when the 1864 season began and had turned 20 when the 1868 season ended and he began his medical career by enrolling at Bristol Medical School on 7 October 1868.[31] In the interim, specifically in 1866, he became widely recognised as the finest cricketer in England. Just after his eighteenth birthday in July 1866, Grace confirmed his potential with an innings of 224 not out for All-England against Surrey at The Oval.[32] It was his maiden first-class century and, according to Harry Altham, he was "thenceforward the biggest name in cricket and the main spectator attraction with the successes (coming) thick and fast".[22] In 1868, Grace scored two centuries in a match, only the second time in cricket history that this is known to have been done, following William Lambert in 1817.[33] Summarising the 1868 season, Simon Rae wrote that Grace was "now indisputably the cricketer of the age, the Champion".[16]

In 1869, Grace was made a member of MCC and scored four centuries in July, including an innings of 180 at The Oval which was achieved during the highest wicket partnership involving Grace in his entire career; he shared 283 runs for the first wicket with Bransby Cooper.[34] Later in the month, Grace scored 122 out of 173 in difficult batting conditions during the North v. South match at Bramall Lane, famously prompting the laconic Tom Emmett to call him a "nonsuch" (i.e., a nonpareil) and declare: "He ought to be made to play with a littler bat".[35]

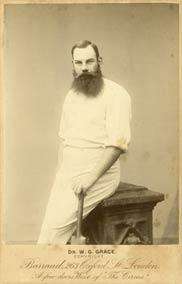

Grace had another outstanding season in 1870, during which Gloucestershire acquired first-class status, and Derek Birley records that, "scorning the puny modern fashion of moustaches", he grew the enormous black beard that made him so recognisable.[36] In addition, his "ample girth" had developed for he weighed 15 stone (95 kg) in his early twenties.[37] Grace was a non-smoker but he enjoyed good food and wine; many years later, when discussing the overheads incurred during Lord Sheffield's profitless tour of Australia in 1891–92, Arthur Shrewsbury commented: "I told you what wine would be drunk by the amateurs; Grace himself would drink enough to swim a ship."[38]

According to Harry Altham, 1871 was Grace's annus mirabilis, except that he produced another outstanding year in 1895.[39] In all first-class matches in 1871, a total of 17 centuries were scored and Grace accounted for 10 of them, including the first century in a first-class match at Trent Bridge.[40] He averaged 78.25 and the next best average by a batsman playing more than a single innings was 39.57, barely more than half his figure. His aggregate for the season was 2,739 runs and this was the first time that anyone had scored 2,000 first-class runs in a season; Harry Jupp was next best with 1,068.[41] Grace produced his season's highlight in the South v North match at The Oval when he made his highest career score to date of 268, having been dismissed by Jem Shaw for nought in the first innings. It was to no avail as the match was drawn.[42] But the occasion produced a memorable and oft-quoted comment by Jem Shaw who ruefully said: "I puts the ball where I likes and he puts it where he likes".[43]

Grace had numerous nicknames during his career including "The Doctor", after he achieved his medical qualification, and "The Old Man", as he reached the veteran stage. He was most auspiciously nicknamed "The Champion".[44][45] He was first acclaimed as "the Champion Cricketer" by Lillywhite's Companion in recognition of his exploits in 1871.[46] However, Grace's great year was marred by the death of his father in December.[47]

Grace and his younger brother Fred still lived with their mother at Downend. Their father had left just enough to maintain the family home but the onus was now on the brothers to increase their earnings from cricket to pay for their medical studies (Fred started his in the autumn of 1872). They achieved this through their involvement as match organisers of the United South of England Eleven which played six matches in the 1872 season including games in Edinburgh and Glasgow, Grace's first visit to Scotland.[48] 1872 was a wet summer and Grace ended his season in early August so that he could join the tour of North America.[49]

Grace became the first batsman to score a century before lunch in a first-class match when he made 134 for Gentlemen of the South versus Players of the South at The Oval in 1873.[50][51] In the same season, he became the first player ever to complete the "double" of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets in a season.[50] He went on to do the double eight times in all:[52]

- 1873 – 2,139 runs and 106 wickets

- 1874 – 1,664 runs and 140 wickets

- 1875 – 1,498 runs and 191 wickets

- 1876 – 2,622 runs and 129 wickets

- 1877 – 1,474 runs and 179 wickets

- 1878 – 1,151 runs and 152 wickets

- 1885 – 1,688 runs and 117 wickets

- 1886 – 1,846 runs and 122 wickets

1873 was the year that some semblance of organisation was brought into county cricket with the introduction of a residence qualification. This was aimed principally at England's outstanding bowler James Southerton who had been playing for both Surrey and Sussex, having been born in one county and living in the other. Southerton chose to play for his county of residence, Surrey, from then on but remained the country's top bowler. The counties agreed on residence but not on a means of deciding a County Championship and so the title, known as "Champion County", remained an unofficial award until 1889. Grace's Gloucestershire had a very strong claim to this unofficial title in 1873 but consensus was that they shared it with Nottinghamshire. These two did not play each other and both were unbeaten in six matches, but Nottinghamshire won five and Gloucestershire won four.[53]

Having toured Australia in the winter of 1873–74, Grace arrived in England on 18 May 1874 and was quickly back into domestic cricket. The 1874 season was very successful for him as he completed a second successive double. Gloucestershire again had a strong claim to the Champion County title although some sources have awarded it to Derbyshire and Grace himself said that it should have gone to Yorkshire.[54] Another good season followed in 1875 when he again completed the double with 1,498 runs and 191 wickets.[55] This was his most successful season as a bowler.

One of the most outstanding phases of Grace's career occurred in the 1876 season, beginning with his career highest score of 344 for Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) v Kent at the St Lawrence Ground, Canterbury, in August.[56] Two days after his innings at Canterbury, he made 177 for Gloucestershire v Nottinghamshire;[57] and two days after that 318 not out for Gloucestershire v Yorkshire,[58] these two innings against counties with exceptionally strong bowling attacks. Thus, in three consecutive innings Grace scored 839 runs and was only out twice. His innings of 344 was the first triple century scored in first-class cricket and broke the record for the highest individual score in all classes of cricket, previously held by William Ward who scored 278 in 1820. Ward's record had stood for 56 years and, within a week, Grace bettered it twice.[59] In 1877, Gloucestershire won the unofficial championship for the third and (to date) final time, largely thanks to another outstanding season by Grace who scored 1,474 runs and took 179 wickets.[60]

There was speculation that Grace intended to retire before the 1878 season to concentrate on his medical career, but he decided to continue playing cricket and may have been influenced by the arrival of the first Australian team to tour England in May. At Lord's on 27 May, the Australians took part in one of the most famous matches of all time when they defeated a strong MCC team, including Grace, by nine wickets in a single day's play.[61] News of the match "spread like wildfire and created a sensation in London and throughout England".[62] The satirical magazine Punch responded to it by publishing a parody of Byron's poem The Destruction of Sennacherib[63] including a wry commentary on Grace's contribution:[64]

The Australians came down like a wolf on the fold,

The Mary'bone Cracks for a trifle were bowled;

And Grace after dinner did not get a run.

Our Grace before dinner was very soon done,

There was bad feeling between Grace and some of the 1878 Australians, especially their manager John Conway; this came to a head on 20 June in a row over the services of Grace's friend Billy Midwinter, an Australian who had played for Gloucestershire in 1877. Midwinter was already in England before the main Australian party arrived and had joined them for their first match in May. On 20 June, Midwinter was at Lord's where he was due to play for the Australians against Middlesex. On the same day, the Gloucestershire team was at The Oval to play Surrey but arrived a man short. As a result, a group of Gloucestershire players led by W. G. and E. M. Grace went to Lord's and persuaded Midwinter to accompany them back to The Oval to make up their numbers.[65] They were pursued by three of the Australians who caught them at The Oval gates where a furious altercation ensued in front of bystanders. At one point, Grace called the Australians "a damned lot of sneaks" (he later apologised). In the end, Grace got his way and Midwinter stayed with Gloucestershire for the rest of the season, although he did not play for the county against the Australians.[66] Afterwards, the row was patched up and Gloucestershire invited the Australians to play the county team, minus Midwinter, at Clifton College.[67] The Australians took a measure of revenge and won easily by 10 wickets, with Fred Spofforth taking 12 wickets and making the top score.[68] It was Gloucestershire's first ever home defeat.[69] The events at The Oval had a postscript during the following winter when W. G. and E. M. were called to account by the Gloucestershire membership because of the expenses they had claimed from Surrey for that match, and which Surrey had refused to authorise.[70]

Despite his troubles in 1878, it was another good season for Grace on the field as he completed a sixth successive double.[60] He made 24 first-class appearances in the season, scoring 1,151 runs, with a highest score of 116, at an average of 28.77 with 1 century and 5 half-centuries. In the field, he held 42 catches and took 152 wickets with a best analysis of 8/23. His bowling average was 14.50; he had 5 wickets in an innings 12 times and 10 wickets in a match 6 times.[60]

Grace missed a large part of the 1879 season because he was doing the final practical for his medical qualification and, for the first time since 1869, he did not complete 1,000 runs, though he did take 105 wickets.[60] Having qualified as a doctor in November 1879, he had to give priority to his new practice in Bristol for the next five years. As a result, his cricket sometimes had to be set aside. He had other troubles including a serious bout of mumps in 1882. He never topped the seasonal batting averages in the 1880s and from 1879 to 1882, he did not complete 1,000 runs in the season.[71]

Grace was badly upset by the death of his brother Fred in 1880, soon after all three brothers played for England against Australia in what is retrospectively recognised as the inaugural Test match in England. Fred's death has been seen as a major factor in the subsequent decline of the Gloucestershire team. Grace made only 13 appearances in 1881. In 1882, he was in the England team that lost the famous "Ashes Match" at The Oval.

In 1883, Grace's medical priorities caused him to miss a Gentlemen v Players match for the first time since 1867. Injury problems restricted his appearances in 1884. Grace achieved his career-best bowling analysis of 10/49 when playing for MCC against Oxford University at The Parks in 1886; and he scored 104 in his only innings to complete a rare "match double".[72] 1886 was the last time he took 100 wickets in a season.[60]

In 1888, Grace scored two centuries in one match v Yorkshire (148 and 153) and labelled this "my champion match".[73] He had reduced his bowling somewhat in the last few seasons and he became an occasional bowler only from 1889. Injury problems, particularly a bad knee, took their toll in the early 1890s and Grace had his worst season in 1891 when he scored no centuries and could only average 19.76.[60] Despite this, few doubted that he should lead the England team on its 1891–92 tour of Australia. Australia, led by Jack Blackham, won the three-match series 2–1.[74]

Following his injury problems and loss of form in 1890 and 1891, Grace rallied somewhat during the next three seasons and reached 1,000 runs each time.

Against all expectation, Grace produced in 1895 a season that has been called his "Indian Summer".[75] He completed his hundredth century playing for Gloucestershire against Somerset in May.[76] Charles Townsend, his batting partner when he reached the milestone, said that as he approached his hundred: "This was the one and only time I ever saw him flustered..." Eventually Sammy Woods bowled a full toss which Grace drove for four to reach his century.[77] He then went on to score 1,000 runs in the month, the first time this had ever been done, with scores of 13, 103, 18, 25, 288, 52, 257, 73 not out, 18 and 169 totalling 1,016 runs between 9 and 30 May.[78] His aggregate for the whole season was 2,346 at an average of 51.00 with nine centuries.[79] He was aged forty-six at the start of the season. Following his "Indian Summer", Grace was the sole recipient of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year award for 1896, the first of only three times that Wisden has restricted the award to a single player, there being normally five recipients.[80]

By the time of his fiftieth birthday in July 1898, Grace had developed a somewhat corpulent figure and had lost his former agility, which meant he was no longer a capable fielder. He remained a very good batsman and at need a useful slow bowler, but he was clearly entering the twilight of his career and was now generally referred to as "The Old Man".[81] As a special occasion, the MCC committee arranged the 1898 Gentlemen v Players match to coincide with his fiftieth birthday and he celebrated the event by scoring 43 and 31 not out, though handicapped by lameness and an injured hand.[82] He terminated his association with both England and Gloucestershire in 1899 and relocated to South London where he joined the new London County club.

With the demise in 1904 of London County as a first-class team, the number of Grace's appearances dwindled over the next four seasons until he called it a day in 1908. His final appearance for the Gentlemen versus the Players was in July 1906 at The Oval.[83] Grace made his final first-class appearance on 20–22 April 1908 for the Gentlemen of England v Surrey at The Oval, where, opening the innings, he scored 15 and 25.[60][84][85]

Gentlemen v Players

In 1864, having scored 5 and 38 for the South Wales club in his first match at The Oval,[26] Grace was outstanding in the next match and scored 170 and 56 not out against the Gentlemen of Sussex at the Royal Brunswick Ground in Hove.[86] His innings of 170 was his first-ever century in a serious match.[87] The third match, against Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) was Grace's debut at Lord's and he was joined by E. M. who had just disembarked from his voyage.[88] Grace scored 50 in the first innings only three days after his sixteenth birthday.[89]

His name now well known in cricketing circles, Grace played for Gentlemen of the South v Players of the South in June 1865[90] when he was still only 16 but already 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) tall and weighing 11 st (70 kg).[91] This match is regarded by CricketArchive as his first-class debut.[92] He bowled extremely well and had match figures of 13 for 84. It was this performance that earned him his first selection for the prestigious Gentlemen v Players fixture.[22]

During this period, before the start of Test cricket in 1877, Gentlemen v Players was the most prestigious fixture in which a player could take part. This is apart from North v South which was technically a fixture of higher quality given that the amateur Gentlemen were usually (until Grace took a hand) outclassed by the professional Players. Grace represented the Gentlemen in their matches against the Players from 1865 to 1906. It was he who enabled the amateurs to meet the paid professionals on level terms and to defeat them more often than not. His ability to master fast bowling was the key factor.[93] Before Grace's debut in the fixture, the Gentlemen had lost 19 consecutive games; of the next 39 games they won 27 and lost only 4.[93] In consecutive innings against the Players from 1871 to 1873, Grace scored 217, 77 and 112, 117, 163, 158 and 70.[93] In his whole career, he scored a record 15 centuries in the fixture.[94]

Grace's 1865 debut in the fixture did not turn the tide as the Players won at The Oval by 118 runs. He played quite well and took seven wickets in the match but could only score 23 and 12 not out.[95] In the second 1865 match, this time at Lord's, the Gentlemen finally ended their losing streak and won by 8 wickets, but it was E. M. Grace, not W. G., who was the key factor with 11 wickets in the match. Even so, Grace made his mark by scoring 34 out of 77–2 in the second innings to steer the Gentlemen to victory.[96]

In 1870, Grace scored 215 for the Gentlemen which was the first double century achieved in the Gentlemen v Players fixture.[97]

Grace last played at Lord's for the Gentlemen in 1899 though he continued to represent the team at other venues until 1906.[98]

Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC)

Grace became a member of Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) in 1869 after being proposed by the treasurer, Thomas Burgoyne, and seconded by the secretary, Robert Allan Fitzgerald.[99] Given an ongoing rift in the sport during the 1860s between the northern professionals and Surrey, MCC feared the loss of its authority should Grace "throw in his lot with the professionals" so it was considered vital for them and their interests to get him onside. As it happens, the dispute was nearly over but it has been said that "MCC regained its authority over the game by hanging onto W. G.'s shirt-tails".[100] Grace wore MCC colours for the rest of his career, playing for them on an irregular basis until 1904, and their red and yellow hooped cap became as synonymous with him as his large black beard.[36] He played for MCC on an expenses only basis but any hopes that the premier club had of keeping him firmly within the amateur ranks would soon be disappointed for his services were much in demand.[36]

Grace, a medical student at the time, was first on the scene when George Summers received the blow on the head that caused his death four days later. This was in the MCC v Nottinghamshire match at Lord's in June 1870.[101] Grace was fielding nearby when Summers was struck and took his pulse. Summers recovered consciousness and Grace advised him to leave the field. Summers did not go to hospital but it transpired later that his skull had been fractured.[102] The Lord's pitch had a poor reputation for being rough, uneven and unpredictable all through the 19th century and many players including Grace considered it dangerous.[103]

Gloucestershire

It is generally understood that Gloucestershire County Cricket Club was formally constituted in 1870, having developed from Dr Henry Grace's West Gloucestershire club.[104] Gloucestershire acquired first-class status when its team played against Surrey at Durdham Down near Bristol on 2, 3 & 4 June 1870.[105] With Grace and his brothers E. M. and Fred playing, Gloucestershire won that game by 51 runs and quickly became one of the best teams in England. The club was unanimously rated Champion County in 1876 and 1877 as well as sharing the unofficial title in 1873 and staking a claim for it in 1874.[106] Surrey and Gloucestershire played a return match at The Oval in July 1870 and Gloucestershire won this by an innings and 129 runs. Grace scored 143, sharing a second wicket partnership with Frank Townsend (89) of 234.[107] The Grace family "ran the show" at Gloucestershire and E. M. was chosen as secretary which, as Birley points out, "put him in charge of expenses, a source of scandal that was to surface before the end of the decade".[36] W. G., though aged only 21, was from the start the team captain and Birley puts this down to his "commercial drawing power".[36]

In 1878, Gloucestershire made its first visit to Old Trafford Cricket Ground in July to play Lancashire and this was the match immortalised by Francis Thompson in his idyllic poem At Lord's.[108] In a match against Surrey at Clifton, the ball lodged in Grace's shirt after he had played it and he seized the opportunity to complete several runs before the fielders forced him to stop. He disingenuously claimed that he would have been out handled the ball if he had removed it and, following a discussion, it was agreed that three runs should be awarded.[109]

In the 1880s, Gloucestershire declined following its heady success in the 1870s. One of the reasons was the early death of W. G.'s younger brother Fred from pneumonia in 1880, there being a view that "the county was never quite the same without him".[110] Apart from W. G. himself, the only players of Fred Grace's calibre at this time were the leading professionals. Unlike the south-east and northern counties, Gloucestershire had neither the large home gates nor the necessary funds that could have secured the services of good quality professionals. This was at a time when a new generation of professionals was appearing with the likes of Billy Gunn, Maurice Read and Arthur Shrewsbury. As a result, Gloucestershire fell away in county competition and could no longer match Nottinghamshire, Surrey and Lancashire who had the strongest sides in the 1880s.[71]

Grace had received an invitation from the Crystal Palace Company in London to help them form the London County Cricket Club.[111] Grace accepted the offer and became the club's secretary, manager and captain with an annual salary of £600.[111] As a result, he severed his connection with Gloucestershire during the 1899 season.[111]

United South of England Eleven (USEE)

The United South of England Eleven (USEE) had been formed by Edgar Willsher in 1865 but the heyday of the travelling teams was over and their organisers were desperate to feature new attractions. Grace had played for the USEE previously and he formally joined the club in 1870 as its match organiser, for which he received payment, but he played for expenses only.[36]

Overseas tours

Grace made three overseas tours during his career. The first was to the United States and Canada with RA Fitzgerald's team in August and September 1872.[112] The expenses of this tour were paid by the Montreal Club who had written to Fitzgerald the previous winter and invited him to form a team. Grace and his all-amateur colleagues made "short work of the weak teams" they faced.[113] The team included two other future England captains in A.N. Hornby, who became a rival of Grace in future years; and the Honourable George Harris, the future Lord Harris, who became a very close friend and a most useful ally. The team met in Liverpool on 8 August and sailed on the SS Sarmatian, docking at Quebec on 17 August. Simon Rae recounts that the bond between Grace and Harris was forged by their mutual sea-sickness. Matches were played in Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, London, New York, Philadelphia and Boston. The team sailed back from Quebec on 27 September and arrived at Liverpool on 8 October.[114] The tour was "a high point of (Grace's) early years" and he "retained fond memories of it" for the rest of his life, calling it "a prolonged and happy picnic" in his ghost-written Reminiscences.[115]

Grace visited Australia in 1873–74 as captain of "W. G. Grace's XI". On the morning of the team's departure from Southampton, Grace responded to well-wishers by saying that his team "had a duty to perform to maintain the honour of English cricket, and to uphold the high character of English cricketers".[116] But both his and the team's performance fell well short of this goal. The tour was not a success and the only positive outcome was the fact of the tour having taken place, ten years after the previous one, as it "gave Australian cricket a much needed fillip".[117] Most of the problems lay with Grace himself and his "overbearing personality" which quickly exhausted all personal goodwill towards him.[118] There was also bad feeling within the team itself because Grace, who normally got on well with professional players, enforced the class divide throughout the tour.[119] In terms of results, the team fared reasonably well following a poor start in which they were beaten by both Victoria and New South Wales. They played 15 matches in all but none are recognised as first-class.[120]

Despite his injury problems in 1891, few doubted that Grace should captain England in Australia the following winter when he led Lord Sheffield's team to Australia in 1891–92. Australia, led by Jack Blackham, won the three-match series 2–1.[74]

Test career

Although the early matches were recognised retrospectively, Test cricket began in 1877 when Grace was already 28 and he made his debut in 1880, scoring England's first-ever Test century against Australia.[121] He played for England in 22 Tests through the 1880s and 1890s, all of them against Australia, and was an automatic selection for England at home, but his only Test-playing tour of Australia was that of 1891–92.[122]

Grace's most significant Test was England v Australia in 1882 at The Oval.[123] Thanks to Spofforth who took 14 wickets in the match, Australia won by 7 runs and the legend of The Ashes was born immediately afterwards. Grace scored only 4 and 32 but he has been held responsible for "firing up" Spofforth. This came about through a typical piece of gamesmanship by Grace when he effected an unsporting, albeit legal, run out of Sammy Jones.[124]

The highest Test wicket partnership involving Grace was at The Oval in 1886 when he and William Scotton scored 170 for the first wicket against Australia. Grace's own score was also 170 and was the highest in his Test career.[125]

An oft-repeated story about Grace is that, in 1896, the Australian pace bowler Ernie Jones bowled a short-pitched delivery so close to his face that it appeared to go through the famous beard which made him so instantly recognisable. Grace reportedly reacted by demanding of Australian captain Harry Trott: "Here, what's all this?" Trott said to Jones: "Steady, Jonah". To which Jones laconically replied: "Sorry, doctor, she slipped". There are multiple variations of the story and, although some sources have recorded that the incident happened in a Test match, there is little doubt that the game in question was the tour opener at Sheffield Park.[126] This is separately confirmed by C.B. Fry and Stanley Jackson who were both playing in the match, Jackson batting with Grace at the time.[127][128]

Grace captained England in the First Test of the 1899 series against Australia at Trent Bridge, when he was 51. By this time his bulk had made him a liability in the field and, afterwards, realising his limitations all too clearly, he decided to stand down and surrendered both his place and the captaincy to Archie MacLaren.[112] It is evident that Grace "plotted" his own omission from the England team by asking C.B. Fry, another selector who had arrived late for their meeting, if he thought that MacLaren should play in the Second Test. Fry answered: "Yes, I do." "That settles it", said Grace, and he promptly retired from international cricket.[129] Explaining his decision later, Grace ruefully admitted of his diminished fielding skills that "the ground was getting a bit too far away".[130]

London County

Having ended his international career in 1899, Grace then began the last phase of his overall first-class career when he joined the new London County Cricket Club, based at Crystal Palace Park, which played first-class matches between 1900 and 1904.[131][132] Grace's presence initially attracted other leading players into the team, including C. B. Fry, Ranjitsinhji and Johnny Douglas, but the increased importance of the County Championship, combined with Grace's inevitable decline in form and the lack of a competitive element in London's matches, led to reduced attendances and consequently the club lost money.[133] Nevertheless, Grace remained an attraction and could still produce good performances. As late as 1902, though aged 54 by the end of the season, he scored 1,187 runs in first-class cricket, with two centuries, at an average of 37.09.[60] London's final first-class matches were played in 1904 and the enterprise folded in 1908.[134]

Later years

Despite his age and bulk, Grace continued to play minor cricket for several years after his retirement from the first-class version. His penultimate match, and the last in which he batted, was for Eltham Cricket Club at Grove Park on 25 July 1914, a week after his 66th birthday. He contributed an undefeated 69 to a total of 155–6 declared, having begun his innings when they were 31–4. Grove Park made 99–8 in reply.[135] The last match of any kind that Grace played in, though he neither batted nor bowled, was for Eltham v Northbrook on 8 August, a few days after the outbreak of the First World War.[136]

On 26 August, in response to news of casualties at the Battle of Mons, Grace wrote a letter to The Sportsman in which he called for the immediate closure of the county cricket season and for all first-class cricketers to set an example and serve their country.[137] It was published next day but did not, as is often supposed, bring an immediate end to the cricket season as one further round of County Championship matches was played.[138]

Grace was reportedly distressed by the war and was known to shake his fist and shout at the German Zeppelins floating over his home in South London. When H. D. G. Leveson-Gower remonstrated that he had not allowed fast bowlers to unsettle him, Grace retorted: "I could see those beggars; I can't see these".[139]

W. G. Grace died at Mottingham on 23 October 1915, aged 67, after suffering a heart attack.[139] His death "shook the nation almost as much as Winston Churchill's fifty years later".[129] He is buried in the family grave at Beckenham Crematorium and Cemetery, Kent.[140]

Style and technique

Grace's approach to cricket

Grace himself had much to say about how to play cricket in his two books Cricket (1891) and Reminiscences (1899), which were both ghost-written. His fundamental opinion was that cricketers are "not born" but must be nurtured to develop their skills through coaching and practice; in his own case, he had achieved his skill through constant practice as a boy at home under the tutelage of his uncle Alfred Pocock.[141]

Although the work ethic was of prime importance in his development, Grace insisted that cricket must also be enjoyable and freely admitted that his family all played in a way that was "noisy and boisterous" with much "chaff" (i.e., a Victorian term for teasing).[142] W. G. and E. M. in particular were noted throughout their careers for being noisy and boisterous on the field. They were extremely competitive and always playing to win. Sometimes this went to extremes (e.g., on one occasion at school, E. M. was so upset about a decision going against him that he went home and took the stumps with him) and developed into the gamesmanship for which E. M. and W. G. were always controversial.[142]

We in Australia did not take kindly to W. G.. For so big a man, he is surprisingly tenacious on very small points. We thought him too apt to wrangle in the spirit of a duo-decimo lawyer over small points of the game.

It was because of gamesmanship and insistence on his rights, as he saw them, that Grace never enjoyed good relations with Australians in general, though he had personal friends like Billy Midwinter and Billy Murdoch.[143] In 1874, an Australian newspaper wrote: "We in Australia did not take kindly to W. G.. For so big a man, he is surprisingly tenacious on very small points. We thought him too apt to wrangle in the spirit of a duo-decimo lawyer over small points of the game."[109]

But he was just the same in England and even his long-term friend Lord Harris agreed that "his gamesmanship added to the fund of stories about him".[144] The point was that Grace "approached cricket as if he were fighting a small war" and he was "out to win at all costs".[66] The Australians understood this twenty years later when Joe Darling, touring England for the first time in 1896, said: "We were all told not to trust the Old Man as he was out to win every time and was a great bluffer".[111]

Batting

"W. G." was a very correct batsman. His left shoulder pointed to the bowler. He held his bat straight and brought it straight through to the ball. His beard hung right over the ball as he stroked it – the ball, I mean, not his beard. He was the most powerful straight-driver I have ever seen. When he drove at a ball I was mighty glad I was behind the stumps.[145]

- Colonel Frank Crozier, 'The Man Who Played With Grace'

With regard to Grace's batsmanship, C.L.R. James held that the best analysis of his style and technique was written by another top-class batsman K.S. Ranjitsinhji in his Jubilee Book of Cricket (co-written with C.B. Fry).[146] Ranjitsinhji wrote that, by his extraordinary skills, Grace "revolutionised cricket and developed most of the techniques of modern batting" and was "the bible of batsmanship".[145] Before him, batsmen would play either forward or back and make a speciality of a certain stroke. Grace "made utility the criterion of style" and incorporated both forward and back play into his repertoire of strokes, favouring only that which was appropriate to the ball being delivered at the moment. In an oft-quoted phrase, Ranjitsinhji said of Grace that "he turned the old one-stringed instrument (i.e., the cricket bat) into a many-chorded lyre" and that "the theory of modern batting is in all essentials the result of W. G.'s thinking and working on the game".[147]

Ranjitsinhji summarised Grace's importance to the development of cricket by writing: "I hold him to be not only the finest player born or unborn, but the maker of modern batting".[148] Cricket writer and broadcaster John Arlott, writing in 1975, supported this view by holding that Grace "created modern cricket".[149]

But Grace's extraordinary skill had already been recognised very early in his career, especially by the professional bowlers. A very prescient comment was made by the laconic Yorkshire and England fast bowler Tom Emmett who, after playing against Grace for the first time in 1869, called him a "nonsuch" (without equal) who "ought to be made to play with a littler bat".[150]

H.S. Altham pointed out that for most of Grace's career, he played on pitches that "the modern schoolboy would consider unfit for a house match" and on grounds without boundaries where every hit including those "into the country" had to be run in full.[93] Rowland Bowen records that 1895, the year of Grace's "Indian Summer", was the season in which marl was first used as a binding agent in the composition of English pitches, its benefit being to ensure "good lasting wickets".[151]

It was through Alfred Pocock's perseverance that Grace had learned to play straight and to develop a sound defence so that he would stop or leave the good deliveries and score off the poor ones.[152] This contrasted him with E. M. who was "always a hitter" and whose basic defence was not as sound.[152] However, as Grace's skills developed, he became a very powerful hitter himself with a full range of shots and, at his best, would score runs freely. Despite being an all-rounder, Grace was also an opening batsman.

Bowling

As a bowler, Grace belonged to what Altham calls the "high, home and easy school of a much earlier day".[130] Using a roundarm action, Grace was adept at varying both his pace and the arc of his slower deliveries which worked in from the leg side of the pitch. The chief feature of his bowling was the excellent length which he consistently maintained. He originally bowled at a consistently fast medium pace but in the 1870s he increasingly adopted his slower style which utilised a leg break.[153] He called his leg break a "leg-tweeker" but he put very little break on the ball, just enough to bring it across from the batsman's legs to the wicket and he invariably posted a fielder in a strategic position on the square leg boundary, a trap which brought occasional success.[153][154] He was unusual in persisting with his roundarm action throughout his career, when almost all other bowlers adopted the new overarm style.[155]

Fielding

In his prime, Grace was noted for his outstanding fielding and was a very strong thrower of the ball; he was once credited with throwing the cricket ball 122 yards during an athletics event at Eastbourne.[156] He attributed this skill to his country-bred childhood in which stone throwing at crows was a daily exercise. In later life, Grace commented upon a decline in English fielding standards and blamed it on "the falling numbers of country-bred boys who strengthen their arms by throwing stones at birds in the fields".[11]

Much of Grace's success as a bowler was due to his magnificent fielding to his own bowling; as soon as he had delivered the ball he covered so much ground to the left that he made himself into an extra mid-off and he took some extraordinary catches in this way.[153]

In his early career, Grace generally fielded at long-leg or cover-point; later he was usually at point (see Fielding positions in cricket).[153] In his prime, he was a fine thrower, a fast runner and a safe catcher.[153]

Grace's amateur status

The expenses enquiry at Gloucestershire took place in January 1879. W. G. and E. M. were forced to answer charges that they had claimed "exorbitant expenses", one of the few times that their money-making activity was seriously challenged.[70] The claim had been submitted to Surrey regarding the controversial 1878 match in which Billy Midwinter was brought in as a late replacement, but Surrey refused to pay it and this provoked the enquiry. The Graces managed to survive "a protracted and stormy meeting" with E. M. retaining his key post as club secretary, although he was forced to liaise in future with a new finance committee and abide by stricter rules.[70]

The incident highlighted an ongoing issue about the nominal amateur status of the Grace brothers. The amateur was, by definition, not a professional and the dictum of the amateur-dominated Marylebone Cricket Club was that "a gentleman ought not to make any profit from playing cricket".[157] Like all amateur players, they claimed expenses for travel and accommodation to and from cricket matches, but there is plenty of evidence that the Graces made even more money by playing than their basic expenses would allow and W. G. in particular "made more than any professional".[158] However, in his later years he had to pay for a locum tenens to run his medical practice while he was playing cricket and he had a reputation for treating his poorer patients without charging a fee.[157] He was paid a salary for his roles as secretary and manager of the London County club.[111] He was the recipient of two national testimonials. The first was presented to him by Lord Fitzhardinge at Lord's on 22 July 1879 in the form of a marble clock, two bronze ornaments and a cheque for £1,458.[70] The second, collected by MCC, the county of Gloucestershire, the Daily Telegraph and The Sportsman, amounted to £9,703 and was presented to him in 1896 in appreciation of his "Indian Summer" season of 1895.[159]

Whatever criticisms may be made of Grace for making money for himself out of cricket, he was "punctilious in his aid when (professional players) were the beneficiaries".[160] For example, when Alfred Shaw's benefit match in 1879 was ruined by rain, Grace insisted on donating to Shaw the proceeds of another match that had been arranged to support Grace's own testimonial fund. After the same thing happened to Edgar Willsher's benefit match, Grace took a select team to play Kent a few days later, the proceeds all going to Willsher. On another occasion, he altered the date of a Gloucestershire match so that he could travel to Sheffield and take part in a Yorkshire player's benefit match, knowing full well the impact that his appearance would have on the gate.[161] As John Arlott recorded, "it was no uncommon sight to see outside a cricket ground":[162]

CRICKET MATCH

Admission 6d

If W. G. Grace plays

Admission 1/–

Grace and his brother Fred faced financial difficulty after their father died in December 1871 as they were still living with their mother who had been left just enough to retain the family home.[163] As medical students, they faced considerable outlay in addition to their living expenses and it became imperative for them to make what they could out of cricket, especially the United South of England Eleven.[163] Grace as its match organiser had to find gaps in the first-class fixture list and then pull together a team to visit a location where a suitable profit could be made.[164] It has been estimated that the standard fee paid to the USEE was £100 for a three-day match with £5 each going to the nine professionals in the team and the other £45 to W. G. and Fred: a sizeable amount in 1872 when £100 was perhaps the equivalent of £3,000-plus at the end of the 20th century.[164] Otherwise, Grace played for expenses but these were loaded as, for example, he is known to have claimed £15 per appearance for Gloucestershire and £20 for representing the Gentlemen.[164] Although the money he was paid is "small beer" compared with 21st-century sports stars, there is no doubt he had a comfortable living out of cricket and made far more money than any contemporary professional. To put it in context, a domestic servant earned less than £50 a year.[165]

Grace's first-class career statistics

According to the statistical record used by CricketArchive, Grace's final first-class appearance in 1908 was his 870th and concluded a first-class career that had lasted 44 seasons from 1865 to 1908, equalling the record for the longest career span held by John Sherman, who played from 1809 to 1852.[166] But according to an older version of Grace's career record, published by Wisden in 1916, Grace played in 878 first-class matches over the same span.[60]

Grace himself regarded the South Wales matches in 1864 as first-class fixtures and refers to them in his Cricketing Reminiscences as "really big" games.[167] He was supported in his view by Lillywhite's Guide to Cricketers (1865 edition) which included his innings at Hove in a list called Scores of 100 or more made since 1850 in first-class matches. Grace's score was one of only six that exceeded 150.[168] Despite Grace's own views on the matter, his "first-class career record" was effectively confirmed by F.S. Ashley-Cooper who produced a list of season-by-season figures to supplement Grace's obituary in the 1916 edition of Wisden Cricketers' Almanack.[169] These figures came to be known as Grace's "traditional" career record and granted him 126 first-class centuries, a total beaten by Jack Hobbs in 1925; it was not until Roy Webber's researches in the 1950s that Ashley-Cooper's list was challenged.[169]

Following further research by the Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians (ACS) in the 1970s and 1980s, an "amended" career record was published which reduced Grace's total of centuries to 124. This was challenged, for historical reasons, by Wisden in 1983 and the current situation re this controversy is that both sides generally accept each other's views. For example, Rae points out that the statisticians are right to criticise Victorian compilers for "including minor matches to enable Grace to reach certain milestones"; but he also respects the view of Grace's contemporaries that "any match in which he played was elevated in status by his very presence".[169][170]

Other sports

Grace was an outstanding athlete as a young man and won the 440 yards (400 m) hurdling title at the National Olympian Games at Crystal Palace in August 1866.[22] In addition to running, he was an excellent thrower, as evidenced when he threw a cricket ball 122 yards (112 m) during an athletics event at Eastbourne.[156]

Grace played football for the Wanderers on several occasions although he did not feature in any of their FA Cup-winning teams.[171]

In later life, after his family moved to Mottingham, Kent, he became very interested in lawn bowls. He founded the English Bowling Association in 1903 and became its first president.[172] He helped found an international competition with Scotland, Ireland and Wales, captaining England from the inaugural international at Crystal Palace in 1903 until 1908. He was also keen on curling.[173][174][175] His interest in golf brought him into intimate contact with one of his biographers Bernard Darwin, who said that Grace played golf "with a mixture of keen seriousness and cheerful noisiness". He could drive straight and sometimes putt well but, for reasons that Darwin could not understand, "he never could play an iron shot well".[176]

Personal life and medical career

Importance of family

Despite living in London for many years, Grace never lost his Gloucestershire accent.[177] His entire life, including his cricket and medical careers, is inseparable from his close-knit family background which was strongly influenced by his father Henry Grace, who set great store by qualifications and was determined to succeed.[178][179] He passed this attitude on to each of his five sons.[178] Therefore, like his father and his brothers, Grace chose a professional career in medicine, though because of his cricketing commitments he did not complete his qualification as a doctor until 1879 when he was 31 years old.[180]

Grace's married life and summary of his medical career

Grace was married on 9 October 1873 to Agnes Nicholls Day (1853–1930), who was the daughter of his first cousin William Day. Two weeks later, they began their honeymoon by taking ship to Australia for Grace's 1873–74 tour.[181] They returned from the tour in May 1874 with Agnes six months pregnant. Their eldest son William Gilbert junior (1874–1905) was born on 6 July.[182] Grace had to catch up with his studies at Bristol Medical School, and he and his wife and son lived at Downend until February 1875 with his mother, brother Fred and sister Fanny.[183]

The Graces moved to London in February 1875, when W. G. was assigned to St Bartholomew's Hospital,[184] and lived at Earl's Court, about five miles from the City.[182] Their second son Henry Edgar (1876–1937) was born in London in July 1876.[185] A ward in the Queen Elizabeth II Wing at St. Bartholomew's Hospital still bears the name "W. G. Grace Ward", caring for patients recovering from cardiothoracic surgery.[186] In the autumn of 1877, the family moved back to Gloucestershire, where they lived with Grace's elder brother Henry, who was a general practitioner. Grace's studies had reached a crucial point with a theoretical backlog to catch up followed by his final practical session. Agnes became pregnant again at this time and their third child Bessie (1878–98) was born in May 1878.[187]

Following the 1878 season, Grace was assigned to Westminster Hospital Medical School for his final year of medical practice and this curtailed his cricket for a time as he did not play in the 1879 season until June. The family moved back to London and lived at Acton.[108] But the upheaval was worthwhile because, in November 1879, Grace finally received his diploma from the University of Edinburgh, having qualified as a Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians (LRCP) and became a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS).[180] After qualifying he worked both in his own practice at Thrissle Lodge, 61 Stapleton Road in Easton, a largely poor district of Bristol, employing two locums during the cricket season. He was the local Public Vaccinator and had additional duties as the Medical Officer to the Barton Regis Union, which involved tending patients in the workhouse.[188]

There are many testimonies from his patients that he was a good doctor, for example: "Poor families knew that they did not need to worry about calling him in, as the bills would never arrive".[157] The family lived at four different addresses close to the practice over the next twenty years and their fourth and last child Charles Butler (1882–1938) was born.[189]

After leaving Gloucestershire in 1900, the Graces lived in Mottingham, a south-east London suburb, not far from the Crystal Palace where he played for London County, or from Eltham, where he played club cricket in his sixties. A blue plaque marks their residence, 'Fairmount', in Mottingham Lane.[134]

Personal tragedies

Grace endured a number of tragedies in his life beginning with the death of his father in December 1871.[47] He was badly upset by the early death of his younger brother Fred in 1880, only two weeks after he, W. G. and E. M. had all played in a Test for England against Australia.[190] In July 1884, Grace's rival A. N. Hornby stopped play in a Lancashire v Gloucestershire match at Old Trafford so that E. M. and W. G. could return home on receipt of a cable reporting the death of Mrs Martha Grace at the age of 72.[190] The greatest tragedy of Grace's life was the loss of his daughter Bessie in 1898, aged only 20, from typhoid. She had been his favourite child.[191] Then, in February 1905, his eldest son W. G. junior died of appendicitis at the age of 30.[192]

Legacy

MCC decided to commemorate Grace's life and career with a Memorial Biography, published in 1919. Its preface begins with this passage:

Never was such a band of cricketers gathered for any tour as has assembled to do honour to the greatest of all players in the present Memorial Biography. That such a volume should go forth under the auspices of the Committee of MCC is in itself unique in the history of the game, and that such an array of cricketers, critics and enthusiasts should pay tribute to its finest exponent has no parallel in any other branch of sport. In itself this presents a noble monument of what W. G. Grace was, a testimony to his prowess and to his personality.[193]

In 1923, the W. G. Grace Memorial Gates were erected at the St John's Wood Road entrance to Lord's.[194] They were designed by Sir Herbert Baker and the opening ceremony was performed by Sir Stanley Jackson, who had suggested the inclusion of the words The Great Cricketer in the dedication.[195] On 12 September 2009, Grace was posthumously inducted into the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame at Lord's. Two of his direct descendants attended the ceremony: Dominic, his great-great-grandson; and George, Dominic's son.[196]

According to Mark Bonham-Carter, H. H. Asquith's grandson, Grace would have been one of the people to be appointed a peer had Asquith's plan to flood the House of Lords with Liberal peers come to fruition.[197] British commemorative postage stamps issued on 16 May 1973 for the County Cricket Centenary featured three sketches of W. G. Grace by Harry Furniss. The values were threepence (then first-class post); seven pence halfpenny; and ninepence.[198] Grace's fame has endured and his large beard in particular remains familiar; for example, Monty Python and the Holy Grail uses his image as "the face of God" during the sequence in which God sends the knights out on their quest for the grail.[199]

In many of the tributes paid to Grace, he was referred to as "The Great Cricketer". H S Altham, for one, described him as "the greatest of all cricketers".[44] John Arlott summarised him as "timeless" and "the greatest (cricketer) of them all".[200] The anti-establishment writer C. L. R. James, in his classic work Beyond a Boundary, included a section "W. G.: Pre-Eminent Victorian", containing four chapters and covering some sixty pages. He declared Grace "the best-known Englishman of his time" and aligned him with Thomas Arnold and Thomas Hughes as "the three most eminent Victorians". James wrote of cricket as "the game he (Grace) transformed into a national institution".[201] Simon Rae also commented upon Grace's eminence in Victorian England by saying that his public recognition was equalled only by Queen Victoria herself and William Ewart Gladstone.[177]

The inaugural edition of Playfair Cricket Annual in 1948 coincided with the centenary of Grace's birth and carried a tribute which spoke of Grace as "King in his own domain" and his "Olympian personality". Playfair went on to say how Grace had "pulverised fast bowling on chancy pitches" and had then "astonished the world" by his deeds during the 1895 "Indian Summer".[154] In the foreword of the same edition, C. B. Fry insisted that Grace would not have started the 1948 season with any notion of being beaten by that season's Australian touring team, for "he was sanguine" and would have put everything he could muster into the task of beating them with no acceptance of defeat "till after it happened".[202] As mentioned in Playfair, both MCC and Gloucestershire arranged special matches on Grace's birthday to commemorate his centenary.[154]

In the 1963 edition of Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, Grace was selected by Neville Cardus as one the Six Giants of the Wisden Century.[203] This was a special commemorative selection requested by Wisden for its 100th edition. The other five players chosen were Sydney Barnes, Don Bradman, Jack Hobbs, Tom Richardson and Victor Trumper.

Derek Birley, who devoted whole passages of his book to criticism of Grace's gamesmanship and moneymaking, wrote that the "bleakness (of the war) was exemplified in November (sic) 1915 by the death of Grace, which seemed depressingly emblematic of the end of an era".[204] Rowland Bowen wrote that "many of Grace's achievements would be rated extremely good by our standards" but "by the standards of his day they were phenomenal: nothing like them had ever been done before".[205] David Frith summed up Grace's legacy to cricket by writing that "his influence lasted long after his final appearance in first-class cricket in 1908 and his death in 1915". "For decades", wrote Frith, "Grace had been arguably the most famous man in England", easily recognisable because of "his beard and his bulk", and revered because of "his batsmanship". Even though his records have been overtaken, "his pre-eminence has not" and he remains "the most famous cricketer of them all", the one who "elevated the game in public esteem".[129]

He is buried at Beckenham Cemetery in Elmers End Rd, Beckenham, Kent.[206] A Public House named after Dr. Grace was built next to the cemetery.[207]

Footnote

• a)^ As described in Grace's first-class career statistics, there are different versions of Grace's first-class career totals as a result of disagreement among cricket statisticians re the status of some matches he played in. Note that this is a statistical issue only and has little, if any, bearing on the historical aspects of Grace's career. In the infobox, the "traditional" first-class figures from Wisden 1916 (as reproduced by Rae, pp. 495–496), are given first and the "amended" figures from CricketArchive follow in parentheses. There is no dispute about Grace's Test career record and those statistics are universally recognised. See Variations in first-class cricket statistics for more information.

References

- 1 2 Rae, p.16.

- ↑ Rae, pp.9–11.

- ↑ Rae, p.11.

- ↑ Rae, pp.12–13.

- ↑ Midwinter, pp.9–10.

- ↑ Grace, Reminiscences, p.1.

- ↑ Grace, Reminiscences, p.2.

- 1 2 3 Midwinter, pp.11–12.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.11.

- 1 2 3 Rae, p.15.

- 1 2 Rae, p.21.

- 1 2 3 Rae, pp.21–22.

- ↑ Rae, p.38.

- ↑ Rae, p.39.

- ↑ Rae, p.63.

- 1 2 3 4 Rae, p.78.

- 1 2 3 Rae, p.34.

- 1 2 Altham, p.124.

- 1 2 Grace, Reminiscences, pp.8–9.

- ↑ "Clifton v South Wales Cricket Club 1859". CricketArchive. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ↑ Rae, p.42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Altham, p.125.

- ↑ "Gentlemen of Somerset v Gentlemen of Gloucestershire in 1863". CricketArchive. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ "Bristol and Didcot XVIII v All-England Eleven in 1863". CricketArchive. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Midwinter, pp.21–22.

- 1 2 3 Grace, p.15.

- ↑ Rae, pp.50–51.

- ↑ "W. G. Grace". CricketArchive. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ "Teams that W. G. Grace played for". CricketArchive. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Grace, p.19.

- ↑ Darwin, p.39.

- ↑ "All-England v Surrey 1866". CricketArchive. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ↑ Rae, p.77.

- ↑ Rae, p.80.

- ↑ Darwin, p.40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Birley, p.105.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.31.

- ↑ Birley, p.148.

- ↑ Altham, p.126.

- ↑ Rae, p.99.

- ↑ "1871 batting averages". CricketArchive. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ↑ "South v North 1871". CricketArchive. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ Rae, p.96.

- 1 2 Altham, p.122.

- ↑ In the famous poem At Lord's by Francis Thompson, Grace was hailed as "The Champion of the Centuries".

- ↑ Midwinter, p.34.

- 1 2 Midwinter, p.35.

- ↑ Rae, pp.102–105.

- ↑ Rae, p.105.

- 1 2 Bowen, p.284.

- ↑ "GS v PS 1873". CricketArchive. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ↑ Webber, Playfair, pp.181–182.

- ↑ Webber, County Championship, pp.12–18.

- ↑ Webber, County Championship, p.18.

- ↑ Webber, Playfair, p.133.

- ↑ "Kent v MCC 1876". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gloucestershire v Nottinghamshire 1876". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gloucestershire v Yorkshire 1876". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ Webber, Playfair, pp.40–41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Rae, pp.495–496.

- ↑ "MCC v Aus 1878". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ↑ Harte, p.102.

- ↑ "The Destruction of Sennacherib". englishhistory.net. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ Altham, p.135.

- ↑ Bowen, p.130, says that Midwinter was still under a contractual obligation to Gloucestershire and that the Australian press had reported this before the team embarked.

- 1 2 Birley, pp.111–112.

- ↑ Midwinter, pp.70–72.

- ↑ "Gloucestershire v Aus 1878". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.72.

- 1 2 3 4 Birley, p.127.

- 1 2 Midwinter, p.79.

- ↑ "OUCC v MCC 1886". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.89.

- 1 2 "Tour itinerary". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.123.

- ↑ "Somerset v Gloucestershire 1895". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ Rae, p. 384.

- ↑ Webber, Playfair, pp.100–101.

- ↑ Webber, Playfair, p.90.

- ↑ "W. G. Grace – Wisden 1896". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. 1896. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ Frith, The Golden Age of Cricket, ch.1.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.129.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Players 1906". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ "List of matches played by W. G. Grace". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Surrey 1908". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gentlemen of Sussex v South Wales Cricket Club 1864". CricketArchive. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.23.

- ↑ Rae, p.54.

- ↑ "MCC v South Wales Cricket Club 1864". CricketArchive. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ "GS v PS 1865". CricketArchive. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ↑ "William_Gilbert_Grace – 1911 article". Britannica Online. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ "First-class matches played by W. G. Grace". CricketArchive. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Altham, p.123.

- ↑ Webber, Playfair, pp.256–257.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Players 1865". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Players 1865". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Players 1870". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Players 1899". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ Rae, pp.78–79.

- ↑ Rae, p.79.

- ↑ "MCC v Nottinghamshire 1870". CricketArchive. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ Rae, p.92.

- ↑ Birley, p.114.

- ↑ Birley, p.104.

- ↑ "Gloucestershire v Surrey 1870". CricketArchive. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ Webber, County Championship, pp.14–20.

- ↑ "Surrey v Gloucestershire 1870". CricketArchive. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- 1 2 Midwinter, p.73.

- 1 2 3 Birley, p.111.

- ↑ Birley, p.132.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Birley, p.162.

- 1 2 Midwinter, p.45.

- ↑ Birley, p.122.

- ↑ Rae, pp.110–129.

- ↑ Rae, p.110.

- ↑ Rae, p.149.

- ↑ Rae, p.188.

- ↑ Rae, p.189.

- ↑ Rae, p.190.

- ↑ "WG Grace's XI in Australia 1873/74". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ "Test Match 1880". CricketArchive. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ↑ "Test matches played by W. G. Grace". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ↑ "Test Match 1882". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ Birley, p.137.

- ↑ "Test Match 1886". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ "LS v Aus 1896". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ↑ Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, 1944 edition – Stanley Jackson's reminiscences.

- ↑ C.B. Fry, Life Worth Living, Trafalgar Square Publishing, 1939

- 1 2 3 Frith, pp.14–15.

- 1 2 Barclays, pp.181–182.

- ↑ Gibson, p.57.

- ↑ Christopher Martin-Jenkins: The Wisden Book of County Cricket (1981), p.441.

- ↑ Midwinter, pp.144–146.

- 1 2 Midwinter, p.146.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.147.

- ↑ Rae, p.486.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.149.

- ↑ Rae, p.487.

- 1 2 Rae, p.490.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.153.

- ↑ Rae, p.17.

- 1 2 Rae, p.19.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.68.

- ↑ Major, p.341.

- 1 2 p136, Richard Whitington, Captains Outrageous, cricket in the seventies, Stanley Paul, 1972

- ↑ James, pp.236–237.

- ↑ James, p.237.

- ↑ Birley, p.167.

- ↑ Arlott, p.1.

- ↑ Rae, p.82.

- ↑ Bowen, p.140.

- 1 2 Rae, p.20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "W. G. Grace's obituary". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. 1916. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- 1 2 3 Playfair Cricket Annual 1948, p.10.

- ↑ Birley, p.110.

- 1 2 Rae, p.69.

- 1 2 3 Bowen, p.112.

- ↑ Birley, p.108.

- ↑ Birley, p.159.

- ↑ Midwinter, pp.73–74.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.74.

- ↑ Arlott, p.6.

- 1 2 Rae, p.102.

- 1 2 3 Rae, p.103.

- ↑ Rae, p.104.

- ↑ "John Sherman's career record". CricketArchive. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ Grace, pp.15–16.

- ↑ Rae, p.52.

- 1 2 3 Rae, p.497.

- ↑ See also: Variations in first-class cricket statistics.

- ↑ Rob Cavallini, The Wanderers F.C.: five time F.A. Cup winners, 2005, ISBN 978-0-9550496-0-6, p.37.

- ↑ "Bowls: W G scores another 100" Retrieved 9 October 2011

- ↑ Midwinter, p.143.

- ↑ Rae, p.478.

- ↑ Darwin, p.106.

- ↑ Darwin, pp.106–107.

- 1 2 Rae, p.1.

- 1 2 Rae, p.3.

- ↑ Rae mentions on page 3 that Dr Henry Grace's medical qualifications were Licenciate of the Society of Apothecaries (LSA) in 1828 and Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) in 1830.

- 1 2 Midwinter, p.75.

- ↑ Midwinter, pp.39–40.

- 1 2 Midwinter, p.54.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.51.

- ↑ www.bartsguild.org

- ↑ Midwinter, p.59.

- ↑ "List of wards at St Bartholomew's Hospital". bartshealth.nhs.uk. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.67.

- ↑ Rae, p.238.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.77.

- 1 2 Midwinter, p.86.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.127.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.140.

- ↑ Gordon, p.v.

- ↑ "Lord's milestones – 1923". MCC. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ Midwinter, p.154.

- ↑ "W. G. Grace inducted into Cricket Hall of Fame". www.thesportscampus.com. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ↑ "Grace worthy of high honour. 20 January 1998". CricInfo. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ↑ Stanley Gibbons, Great Britain Concise Stamp Catalogue, 1997 edition, pp.96–97.

- ↑ In the commentary track of the DVD release, Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones acknowledge the use of Grace's image.

- ↑ Arlott, p.256.

- ↑ James, ch.14.

- ↑ C. B. Fry, Playfair Cricket Annual 1948, p.4.

- ↑ Cardus, Neville (1963). "Six Giants of the Wisden Century". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ↑ Birley, p.208.

- ↑ Bowen, p.108.

- ↑ "Beckenham Cemetery". Dignity. 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ "Beckenham Restaurants: Pubs and Bars". Beckenham.NET. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

Bibliography