Vlasov equation

The Vlasov equation is a differential equation describing time evolution of the distribution function of plasma consisting of charged particles with long-range (for example, Coulomb) interaction. The equation was first suggested for description of plasma by Anatoly Vlasov in 1938[1] (see also [2]) and later discussed by him in detail in a monograph.[3]

Difficulties of the standard kinetic approach

First, Vlasov argues that the standard kinetic approach based on the Boltzmann equation has difficulties when applied to a description of the plasma with long-range Coulomb interaction. He mentions the following problems arising when applying the kinetic theory based on pair collisions to plasma dynamics:

- Theory of pair collisions disagrees with the discovery by Rayleigh, Irving Langmuir and Lewi Tonks of natural vibrations in electron plasma.

- Theory of pair collisions is formally not applicable to Coulomb interaction due to the divergence of the kinetic terms.

- Theory of pair collisions cannot explain experiments by Harrison Merrill and Harold Webb on anomalous electron scattering in gaseous plasma.[4]

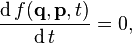

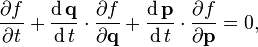

Vlasov suggests that these difficulties originate from the long-range character of Coulomb interaction. He starts with the collisionless Boltzmann equation (sometimes called the Vlasov equation, anachronistically in this context), in generalized coordinates:

explicitly a PDE:

and adapted it to the case of a plasma, leading to the systems of equations shown below.[5]

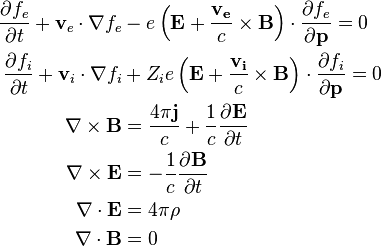

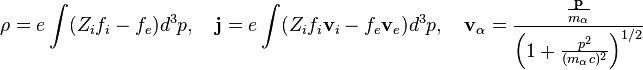

The Vlasov–Maxwell system of equations (gaussian units)

Instead of collision-based kinetic description for interaction of charged particles in plasma, Vlasov utilizes a self-consistent collective field created by the charged plasma particles. Such a description uses distribution functions  and

and  for electrons and (positive) plasma ions. The distribution function

for electrons and (positive) plasma ions. The distribution function  for species α describes the number of particles of the species α having approximately the momentum

for species α describes the number of particles of the species α having approximately the momentum  near the position

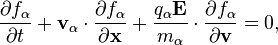

near the position  at time t. Instead of the Boltzmann equation, the following system of equations was proposed for description of charged components of plasma (electrons and positive ions):

at time t. Instead of the Boltzmann equation, the following system of equations was proposed for description of charged components of plasma (electrons and positive ions):

Here e is the electron charge, c is the speed of light, mi is the mass of the ion,  and

and  represent collective self-consistent electromagnetic field created in the point

represent collective self-consistent electromagnetic field created in the point  at time moment t by all plasma particles. The essential difference of this system of equations from equations for particles in an external electromagnetic field is that the self-consistent electromagnetic field depends in a complex way on the distribution functions of electrons and ions

at time moment t by all plasma particles. The essential difference of this system of equations from equations for particles in an external electromagnetic field is that the self-consistent electromagnetic field depends in a complex way on the distribution functions of electrons and ions  and

and  .

.

The Vlasov–Poisson equation

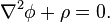

The Vlasov–Poisson equations are an approximation of the Vlasov–Maxwell equations in the nonrelativistic zero-magnetic field limit:

and Poisson's equation for self-consistent electric field:

Here qα is the particle's electric charge, mα is the particle's mass,  is the self-consistent electric field,

is the self-consistent electric field,  the self-consistent electric potential and ρ is the electric charge density.

the self-consistent electric potential and ρ is the electric charge density.

Vlasov–Poisson equations are used to describe various phenomena in plasma, in particular Landau damping and the distributions in a double layer plasma, where they are necessarily strongly non-Maxwellian, and therefore inaccessible to fluid models.

Moment equations

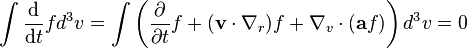

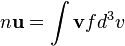

In fluid descriptions of plasmas (see plasma modeling and magnetohydrodynamics (MHD)) one does not consider the velocity distribution. This is achieved by replacing  with plasma moments such as number density n, flow velocity u and pressure p.[6] They are named plasma moments because the n-th moment of

with plasma moments such as number density n, flow velocity u and pressure p.[6] They are named plasma moments because the n-th moment of  can be found by integrating

can be found by integrating  over velocity. These variables are only functions of position and time, which means that some information is lost. In multifluid theory, the different particle species are treated as different fluids with different pressures, densities and flow velocities. The equations governing the plasma moments are called the moment or fluid equations.

over velocity. These variables are only functions of position and time, which means that some information is lost. In multifluid theory, the different particle species are treated as different fluids with different pressures, densities and flow velocities. The equations governing the plasma moments are called the moment or fluid equations.

Below the two most used moment equations are presented (in SI units). Deriving the moment equations from the Vlasov equation requires no assumptions about the distribution function.

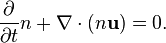

Continuity equation

The continuity equation describes how the density changes with time. It can be found by integration of the Vlasov equation over the entire velocity space.

After some calculations, one ends up with

The number density n, and the momentum density nu, are zeroth and first order moments:

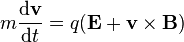

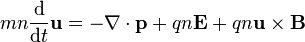

Momentum equation

The rate of change of momentum of a particle is given by the Lorentz equation:

By using this equation and the Vlasov Equation, the momentum equation for each fluid becomes

,

,

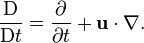

where p is the pressure tensor. The material derivative is

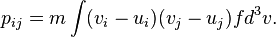

The pressure tensor is defined as the particle mass times the covariance matrix of the velocity:

The frozen-in approximation

As for ideal MHD, the plasma can be considered as tied to the magnetic field lines when certain conditions are fulfilled. One often says that the magnetic field lines are frozen into the plasma. The frozen-in conditions can be derived from Vlasov equation.

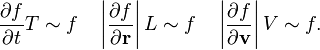

We introduce the scales T, L and V for time, distance and speed respectively. They represent magnitudes of the different parameters which give large changes in  . By large we mean that

. By large we mean that

We then write

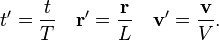

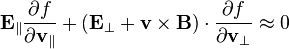

Vlasov equation can now be written

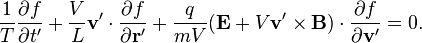

So far no approximations have been done. To be able to proceed we set  , where

, where  is the gyro frequency and R is the gyroradius. By dividing by ωg, we get

is the gyro frequency and R is the gyroradius. By dividing by ωg, we get

If  and

and  , the two first terms will be much less than

, the two first terms will be much less than  since

since  and

and  due to the definitions of T, L and V above. Since the last term is of the order of

due to the definitions of T, L and V above. Since the last term is of the order of  , we can neglect the two first terms and write

, we can neglect the two first terms and write

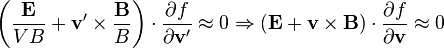

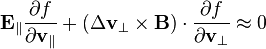

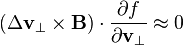

This equation can be decomposed into a field aligned and a perpendicular part:

The next step is to write  , where

, where

It will soon be clear why this is done. With this substitution, we get

If the parallel electric field is small,

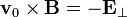

This equation means that the distribution is gyrotropic.[7] The mean velocity of a gyrotropic distribution is zero. Hence,  is identical with the mean velocity, u, and we have

is identical with the mean velocity, u, and we have

To summarize, the gyro period and the gyro radius must be much smaller than the typical times and lengths which give large changes in the distribution function. The gyro radius is often estimated by replacing V with the thermal velocity or the Alfvén velocity. In the latter case R is often called the inertial length. The frozen-in conditions must be evaluated for each particle species separately. Because electrons have much smaller gyro period and gyro radius than ions, the frozen-in conditions will more often be satisfied.

See also

- A. A. Vlasov, Many-Particle Theory and Its Application to Plasma, Gordon and Breach, 1961.

- List of plasma (physics) articles

References

- ↑ A. A. Vlasov (1938). "On Vibration Properties of Electron Gas". J. Exp. Theor. Phys. (in Russian) 8 (3): 291.

- ↑ A. A. Vlasov (1968). "The Vibrational Properties of an Electron Gas". Soviet Physics Uspekhi 10 (6): 721. Bibcode:1968SvPhU..10..721V. doi:10.1070/PU1968v010n06ABEH003709.

- ↑ A. A. Vlasov (1945). Theory of Vibrational Properties of an Electron Gas and Its Applications.

- ↑ H. J. Merrill & H. W. Webb (1939). "Electron Scattering and Plasma Oscillations". Physical Review 55 (12): 1191. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55.1191M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.1191.

- ↑ "Vlasov equation?", M. Hénon, Astronomy and Astrophysics 114, #1 (October 1982), pp. 211-212, Bibcode: 1982A&A...114..211H

- ↑ W. Baumjohann and R. A. Treumann, Basic Space Plasma Physics, Imperial College Press, 1997

- ↑ P. C. Clemmow and J. Dougherty, Electrodynamics of Particles and Plasmas, Addison-Wesley series in advanced physics, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1969