Vivien Thomas

| Vivien Thomas | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Thomas' 1969 portrait by Bob Gee | |

| Born |

Vivien Theodore Thomas August 29, 1910 New Iberia, Louisiana, United States |

| Died | November 26, 1985 (aged 75) |

| Education | Pearl High School |

|

Medical career | |

| Profession | Instructor of Cardiac Surgery |

| Institutions | Johns Hopkins Hospital, Vanderbilt University Hospital |

| Research | Blue baby syndrome |

Vivien Theodore Thomas (August 29, 1910 – November 26, 1985)[1] was an African-American surgical technician who developed the procedures used to treat blue baby syndrome in the 1940s. He was the assistant to surgeon Alfred Blalock in Blalock's experimental animal laboratory at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and later at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. He served as supervisor of the surgical laboratories at Johns Hopkins for 35 years. In 1976 Hopkins awarded him an honorary doctorate and named him an instructor of surgery for the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.[2] Without any education past high school, Thomas rose above poverty and racism to become a cardiac surgery pioneer and a teacher of operative techniques to many of the country's most prominent surgeons.

There is a television film based on his life entitled Something the Lord Made which premiered May 2004 on HBO.

Early life

Thomas was born in New Iberia, Louisiana, the son of Mary (Eaton) and William Marco Thomas.[3][4] The grandson of a slave, he attended Pearl High School in Nashville in the 1920s.[5] Thomas had hoped to attend college and become a doctor, but the Great Depression derailed his plans.[6] He worked at Vanderbilt University in the summer of 1929 doing carpentry[7] but was laid off in the fall. In that same year, Thomas enrolled in the Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial College as a premedical student.[8] In the wake of the stock market crash in October, Thomas put his educational plans on hold, and, through a friend, in February 1930 secured a job as surgical research technician with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Vanderbilt University.[9] On his first day of work, Thomas assisted Blalock with a surgical experiment on a dog.[10] At the end of Thomas's first day, Blalock told Thomas they would do another experiment the next morning. Blalock told Thomas to "come in and put the animal to sleep and get it set up". Within a few weeks, Thomas was starting surgery on his own.[11] Thomas was classified and paid as a janitor,[12] despite the fact that by the mid-1930s, he was doing the work of a Postdoctoral researcher in the lab.

Before meeting Blalock, Thomas married Clara and had two daughters.[13] When Nashville's banks failed nine months after starting his job with Blalock and Thomas' savings were wiped out,[9] he abandoned his plans for college and medical school, relieved to have even a low-paying job as the Great Depression deepened.

Working with Blalock

Thomas and Blalock did groundbreaking research into the causes of hemorrhagic[14] and traumatic shock.[15] This work later evolved into research on crush syndrome[16] and saved the lives of thousands of soldiers on the battlefields of World War II.[16] In hundreds of experiments, the two disproved traditional theories which held that shock was caused by toxins in the blood.[17] Blalock, a highly original scientific thinker and something of an iconoclast, had theorized that shock resulted from fluid loss outside the vascular bed and that the condition could be effectively treated by fluid replacement.[17] Assisted by Thomas, he was able to provide incontrovertible proof of this theory, and in so doing, he gained wide recognition in the medical community by the mid-1930s. At this same time, Blalock and Thomas began experimental work in vascular and cardiac surgery,[14] defying medical taboos against operating upon the heart. It was this work that laid the foundation for the revolutionary lifesaving surgery they were to perform at Johns Hopkins a decade later.

Working at Johns Hopkins

By 1940, the work Blalock had done with Thomas placed him at the forefront of American surgery, and when he was offered the position of Chief of Surgery at his alma mater Johns Hopkins in 1941,[18] he requested that Thomas accompany him.[18] Thomas arrived in Baltimore with his family in June of that year,[19] confronting a severe housing shortage and a level of racism worse than they had endured in Nashville.[20] Hopkins, like the rest of Baltimore, was rigidly segregated, and the only black employees at the institution were janitors. When Thomas walked the halls in his white lab coat, many heads turned.

Blue baby syndrome

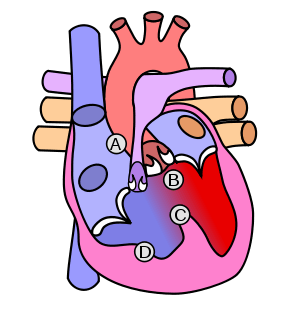

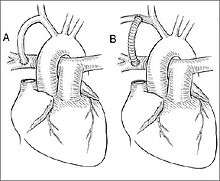

In 1943, while pursuing his shock research, Blalock was approached by renowned pediatric cardiologist Helen Taussig,[21] who was seeking a surgical solution to a complex and fatal four-part heart anomaly called tetralogy of Fallot (also known as blue baby syndrome, although other cardiac anomalies produce blueness, or cyanosis). In infants born with this defect, blood is shunted past the lungs, thus creating oxygen deprivation and a blue pallor.[21] Having treated many such patients in her work in Hopkins's Harriet Lane Home, Taussig was desperate to find a surgical cure. According to the accounts in Thomas's 1985 autobiography and in a 1967 interview with medical historian Peter Olch, Taussig suggested only that it might be possible to "reconnect the pipes"[22] in some way to increase the level of blood flow to the lungs but did not suggest how this could be accomplished. Blalock and Thomas realized immediately that the answer lay in a procedure they had perfected for a different purpose in their Vanderbilt work, involving the anastomosis (joining) of the subclavian artery to the pulmonary artery, which had the effect of increasing blood flow to the lungs.[22] Thomas was charged with the task of first creating a blue baby-like condition in a dog, and then correcting the condition by means of the pulmonary-to-subclavian anastomosis.[23] Among the dogs on whom Thomas operated was one named Anna, who became the first long-term survivor of the operation and the only animal to have her portrait hung on the walls of Johns Hopkins. In nearly two years of laboratory work involving 200 dogs, Thomas was able to replicate two of the four cardiac anomalies involved in tetralogy of Fallot.[24] He did demonstrate that the corrective procedure was not lethal, thus persuading Blalock that the operation could be safely attempted on a human patient.[25] Even though Thomas knew he was not allowed to operate on patients at that time, he still followed Blalock's rules and assisted him during surgery.[26]

Decisive surgery

On November 29, 1944, the procedure was first tried on an eighteen-month-old infant named Eileen Saxon.[26] The blue baby syndrome had made her lips and fingers turn blue, with the rest of her skin having a very faint blue tinge. She could only take a few steps before beginning to breathe heavily. Because no instruments for cardiac surgery then existed, Thomas adapted the needles and clamps for the procedure from those in use in the animal lab.[27] During the surgery itself, at Blalock's request, Thomas stood on a step stool at Blalock's shoulder and coached him step by step through the procedure.[28] Thomas performed the operation hundreds of times on a dog, whereas Blalock only once as Thomas' assistant.[28] The surgery was not completely successful, though it did prolong the infant's life for several months.[29] Blalock and his team operated again on an 11-year-old girl, this time with complete success, and the patient was able to leave the hospital three weeks after the surgery.[29] Next, they operated upon a six-year-old boy, who dramatically regained his color at the end of the surgery.[29] The three cases formed the basis for the article that was published in the May 1945 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, giving credit to Blalock and Taussig for the procedure. Thomas received no mention.[27]

News of this groundbreaking story was circulated around the world by the Associated Press.[27] Newsreels touted the event, greatly enhancing the status of Johns Hopkins and solidifying the reputation of Blalock, who had been regarded as a maverick up until that point by some in the Hopkins old guard.[30] Thomas' contribution remained unacknowledged, both by Blalock and by Hopkins. Within a year, the operation known as the Blalock-Taussig shunt had been performed on more than 200 patients at Hopkins, with parents bringing their suffering children from thousands of miles away.[30]Thomas's surgical techniques included one he developed in 1946 for improving circulation in patients whose great vessels (the aorta and the pulmonary artery) were transposed.[31] A complex operation called an atrial septectomy, the procedure was executed so flawlessly by Thomas that Blalock, upon examining the nearly undetectable suture line, was prompted to remark, "Vivien, this looks like something the Lord made".[31]To the host of young surgeons Thomas trained during the 1940s,[32] he became a figure of legend, the model of a dexterous and efficient cutting surgeon. "Even if you'd never seen surgery before, you could do it because Vivien made it look so simple," the renowned surgeon Denton Cooley[26] told Washingtonian magazine in 1989. "There wasn't a false move, not a wasted motion, when he operated." Surgeons like Cooley, along with Alex Haller,[33] Frank Spencer,[34] Rowena Spencer,[35] and others credited Thomas with teaching them the surgical technique that placed them at the forefront of medicine in the United States. Despite the deep respect Thomas was accorded by these surgeons and by the many black lab technicians he trained at Hopkins, he was not well paid.[36] He sometimes resorted to working as a bartender, often at Blalock's parties. This led to the peculiar circumstance of his serving drinks to people he had been teaching earlier in the day. Eventually, after negotiations on his behalf by Blalock, he became the highest paid technician at Johns Hopkins by 1946, and by far the highest paid African-American on the institution's rolls.[37] Although Thomas never wrote or spoke publicly about his ongoing desire to return to college and obtain a medical degree, his widow, the late Clara Flanders Thomas, revealed in a 1987 interview with Washingtonian writer Katie McCabe that her husband had clung to the possibility of further education throughout the blue baby period and had only abandoned the idea with great reluctance. Mrs. Thomas stated that in 1947, Thomas had investigated the possibility of enrolling in college and pursuing his dream of becoming a doctor, but had been deterred by the inflexibility of Morgan State University, which refused to grant him credit for life experience and insisted that he fulfill the standard freshman requirements. Realizing that he would be 50 years old by the time he completed college and medical school, Thomas decided to give up the idea of further education.

Relations with Blalock

Blalock's approach to the issue of Thomas's race was complicated and contradictory throughout their 34-year partnership. On the one hand, he defended his choice of Thomas to his superiors at Vanderbilt and to Hopkins colleagues, and he insisted that Thomas accompany him in the operating room during the first series of tetralogy operations. On the other hand, there were limits to his tolerance, especially when it came to issues of pay, academic acknowledgment, and his social interaction outside of work. Tension with Blalock continued to build when he failed to recognize the contributions that Thomas had made in the world-famous blue baby procedure, which led to a rift in their relationship. Thomas was absent in official articles about the procedure, as well as in team pictures that included all of the doctors involved in the procedure.[38]

After Blalock's death from cancer in 1964 at the age of 65,[39] Thomas stayed at Hopkins for 15 more years. In his role as director of Surgical Research Laboratories, he mentored a number of African-American lab technicians as well as Hopkins' first black cardiac resident, Levi Watkins, Jr., whom Thomas assisted with his groundbreaking work in the use of the automatic implantable defibrillator.

Thomas' nephew, Koco Eaton, graduated from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, trained by many of the physicians his uncle had trained. Eaton trained in orthopedics and is now the team doctor for the Tampa Bay Rays.

Institutional acknowledgment

In 1968, the surgeons Thomas trained — who had then become chiefs of surgical departments throughout America — commissioned the painting of his portrait (by Bob Gee, oil on canvas, 1969, The Johns Hopkins Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives)[40] and arranged to have it hung next to Blalock's in the lobby of the Alfred Blalock Clinical Sciences Building.

In 1976, Johns Hopkins University presented Thomas with an honorary doctorate.[2] Because of certain restrictions, he received an Honorary Doctor of Laws, rather than a medical doctorate, but it did allow the staff and students of Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine to call him doctor. After having worked there for 37 years, Thomas was also finally appointed to the faculty of the School of Medicine as Instructor of Surgery.[2]

In July 2005, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine began the practice of splitting incoming first-year students into four colleges, each named for famous Hopkins faculty members that had major impacts on the history of medicine. Thomas was chosen as one of the four, along with Helen Taussig, Florence Sabin, and Daniel Nathans.

Legacy

Following his retirement in 1979, Thomas began work on an autobiography.[41] He died of pancreatic cancer on November 26, 1985, and the book was published just days later. Having learned about Thomas on the day of his death, Washingtonian writer Katie McCabe brought his story to public attention in a 1989 article entitled "Like Something the Lord Made", which won the 1990 National Magazine Award for Feature Writing and inspired filmmaker Andrea Kalin to make the PBS documentary Partners of the Heart,[42] which was broadcast in 2003 on PBS's American Experience and won the Organization of American Historians's Erik Barnouw Award for Best History Documentary in 2004.[43] McCabe's article, brought to Hollywood by Washington, D.C. dentist Irving Sorkin,[44] formed the basis for the Emmy and Peabody Award-winning 2004 HBO film Something the Lord Made.

Thomas's legacy as an educator and scientist continued with the institution of the Vivien Thomas Young Investigator Awards, given by the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesiology beginning in 1996. In 1993, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation instituted the Vivien Thomas Scholarship for Medical Science and Research sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. In fall 2004, the Baltimore City Public School System opened the Vivien T. Thomas Medical Arts Academy, and on January 29, 2008, MedStar Health unveiled the first "Rx for Success" program at the Academy, joining the conventional curriculum with specialized coursework geared to the health care professions. In the halls of the school hangs a replica of Thomas's portrait commissioned by his surgeon-trainees in 1969.[45] The Journal Of Surgical Case Reports announced in January 2010 that its annual prizes for the best case report written by a doctor and best case report written by a medical student would be named after Thomas.[46]

See also

References

- ↑ Johnson, George D. (2011). Profiles in Hue. Light of the Savior Ministries. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4568-5119-4. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Vivien T. Thomas, L.L.D.". Medical archives. Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 3. ISBN 0-8122-7989-1.

- ↑ "Vivien Theodore Thomas". taneya-kalonji.com. Taneya & Kalonji. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 5.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 8.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 7.

- ↑ "The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions". medicalarchives.jhmi.edu. The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. 2006. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 9.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 12.

- ↑ (1985) Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery: Vivien Thomas and His Work with Alfred Blalock, University of Pennsylvania Press, pages 9-13. ISBN 0-8122-7989-1.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 43.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 48.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 33.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 48.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 66.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 67.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 38.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 57.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 58.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 80.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 89.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 82.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 86.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 91.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 92.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 97.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 94.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 96.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 99.

- 1 2 Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 122.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 109.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. pp. 1154–155.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 175 and p.194.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 115 and p.121.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. pp. 130–135.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 142.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Mr. Vivien Thomas Discusses Dr. Alfred Blalock. p. 21.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 214.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 219.

- ↑ Partners of the Heart: Vivien Thomas and his Work with Alfred Blalock, ISBN 0-8122-1634-2

- ↑ "Almost a Miracle". Hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

- ↑ OAH.org, OAH Erik Barnouw Award Winners

- ↑ "Like Something the Lord Made; The Vivien Thomas Story". Washingtonian.com. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

- ↑ Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery. p. 219.

- ↑ JSCR Website

Bibliography

- (1989) McCabe Katie,"Like Something the Lord Made",.Washingtonian magazine, August 1989. Reprinted in Feature Writing for Newspapers and Magazines: The Pursuit of Excellence, ed. by Jay Friedlander and John Lee. May also be accessed via the Washingtonian.

- (1985) Thomas Vivien, Partners of the Heart: Vivien Thomas and His Work with Alfred Blalock (originally published as Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery: Vivien Thomas and His Work with Alfred Blalock), University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1634-2

- Thomas, Vivien. Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery, Vivien Thomas and his Work with Alfred Blalock. ISBN 0-8122-7989-1.

- (2003) Timmermans Stefan, "A Black Technician and Blue Babies" in Social Studies of Science 33:2 (April 2003), 197–229.

- (2006) Tsung O. Cheng, "Hamilton Naki and Christiaan Barnard Versus Vivien Thomas and Alfred Blalock: Similarities and Dissimilarities" in American Journal of Cardiology 97:3 (February 1, 2006), 435–436.

- (2003). Partners of the Heart. American Experience

- (2004) "Something the Lord Made", HBO movie, Portrayed by Mos Def

External links

|