Virtual queue

Virtual queuing is a concept used in inbound call centers. Call centers use an Automatic Call Distributor (ACD) to distribute incoming calls to specific resources (agents) in the center. ACDs hold queued calls in First In, First Out order until agents become available. From the caller’s perspective, without virtual queuing they have only two choices: wait until an agent resource becomes available, or abandon (hang up) and try again later. From the call center’s perspective, a long queue results in many abandoned calls, repeat attempts, and customer dissatisfaction.

Virtual queuing systems allow customers to receive callbacks instead of waiting in an ACD queue. This solution is analogous to the “fast lane” option (e.g. Disney's FASTPASS) used at amusement parks, which often have long queues to ride the various coasters and attractions. A computerized system allows park visitors to secure their place in a “virtual queue” rather than waiting in a physical queue.

In the brick-and-mortar retail and business world, virtual queuing for large organizations similar to the FASTPASS and Six Flags' Flash Pass, have been in use successfully since 1999 and 2001 respectively. For small businesses, the virtual queue management solutions come in two types: (a) based on SMS text notification and (b) apps on smartphones and tablet devices, with in-app notification and remote queue status views.

Overview

While there are several different varieties of virtual queuing systems, a standard First In, First Out that maintains the customer's place in line is set to monitor queue conditions until the Estimated Wait Time (EWT) exceeds a predetermined threshold. When the threshold is exceeded, the system intercepts incoming calls before they enter the queue. It informs customers of their EWT and offers the option of receiving a callback in the same amount of time as if they waited on hold.

If customers choose to remain in a queue (also known as que or q for short), their calls are routed directly to the queue. Customers who opt for a callback are prompted to enter their phone number and then hang up the phone. A “virtual placeholder” maintains the customers' position in the queue while the ACD queue is worked off. The virtual queuing system monitors the rate at which calls in queue are worked off and launches an outbound call to the customer moments before the virtual placeholder is due to reach the top of the queue. When the callback is answered by the customer, the system asks for confirmation that the correct person is on the line and ready to speak with an agent. Upon receiving confirmation, the system routes the call to the next available agent resource, who handles it as a normal inbound call.

Call centers don't measure this "virtual queue" time as "queue time" because the caller is free to pursue other activities instead of listening to hold music and announcements. The voice circuit is released between the ACD and the telecommunications network, so the call does not accrue any queue time or telecommunications charges.

Comparison of queuing options

Comparing traditional and virtual queuing timelines shows the difference in the customer experience. In this first example, the customer waits in a traditional queue for 12 minutes. When he's finally connected with an agent, he talks for 3 minutes - but some of that time is spent complaining about his time spent in the queue. Note that many customers in this situation would abandon the queue before reaching an agent, and retry the call later, resulting in additional telecom costs for the contact center and skewed call center metrics.

In the second example, the customer is treated by a virtual queuing system. He listens to a greeting that informs him of his EWT and offers him the option of receiving a callback rather than waiting in a queue. He prefers to remain in the queue, so his call enters the queue and he is connected with an agent when his turn arrives. It's unlikely that he will waste time complaining because he was informed of his estimated wait and presented with options for managing his time. This is indicated in the example with “Saved Talk Time”. He may also be less likely to abandon the call because he was informed and made a conscious choice to remain in the queue.

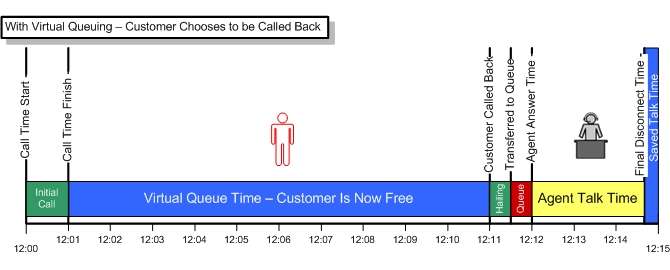

The third example shows a customer who is treated by the virtual queuing system and chooses to receive a callback in the same amount of time as if he waits in queue. After entering his phone number and speaking his name, the customer hangs up the phone and a virtual placeholder reserves his spot in the queue. This "virtual queue time" saves inbound telecommunications charges (because the customer is not on the line) and frees up the customer's valuable time. When the placeholder is near the front of the queue, the system calls the customer back, greets him, and puts him at the front of the queue, where he is next to be answered by an agent. Since the customer has had a positive experience, he may be less likely to complain about a long wait.

Impact

Virtual queuing impacts the call center metrics in many ways. Queue time is normally measured as Average Speed-to-Answer (ASA). When callers are offered the option to receive a First In, First Out callback, the callers’ acceptance rates are typically 45% to 55%. Therefore, about half of the calls that would normally queue for 5 to 10 minutes will now only accrue a speed-to-answer (ASA) of approximately 10 seconds. Likewise, these callbacks with a shorter ASA will score within the Service Level objective. Since callers cannot abandon while in a virtual queue, the overall number of abandoned calls will decrease. The impact on customer satisfaction is positive, but tends to be more difficult to measure objectively. Virtual queuing can result in better customer experiences and improved contact center operations. But there are several types of virtual queuing systems.

First In, First Out Queuing vs. Scheduled Queuing

The two main types of virtual queuing systems are First In, First Out (FIFO) and Scheduled.

FIFO systems allow customers to maintain their place in the queue and receive a callback in the same amount of time as if they waited on hold. Virtual placeholders maintain the integrity of the queue and provide added convenience to customers without penalty for avoiding traditional hold time.

The earlier examples looked in detail at how FIFO virtual queuing works. Scheduled systems offer the same convenience of a callback without waiting on hold, but differ from FIFO systems in that customers do not maintain their place in queue.

Scheduled callback systems offer customers a callback at some time in the future - but after the time when their call would be answered if they remained in queue. If queue times are excessive, it may be more convenient for customers to receive a callback later in the day, or even later in the week. Among the various types of scheduled callback systems, there are variations, each with its strengths and weaknesses.

Datebook-type scheduling systems allow customers to schedule appointments for up to 7 days in the future. Contact centers can block out times that are unavailable for scheduling and limit the number of appointments available. Datebook systems also allow customers who reach your center after business hours to schedule an appointment during normal operating times.

Timer scheduling systems promise a callback in a preset amount of time, regardless of queue conditions. While this ensures an on-time callback for the customer, a surge in call volume or staff reduction due to a shift change can create a bottleneck in the contact center's queue, lengthening wait times.

Forecast-based scheduling systems only offer appointments during times when the contact center anticipates a drop in demand based on workforce planning forecasts. These times may not be convenient for the customer, and the contact center runs the risk of a bottleneck if the anticipated reduction in demand or increase in staffing doesn't occur.

While both First In, First Out and Scheduled queuing can provide significant performance benefits to the call center, some queuing systems only allow for scheduled callbacks, though FIFO is clearly preferred. The limitations of these forced-scheduling systems do not provide an optimal customer experience, and their reliance on countdown timers or call traffic forecasts may negatively impact contact center operations. Timer scheduling and forced-scheduling systems can cause a “stall” or “chase” condition to occur in the queue, reducing call center efficiency.

The best bet for improving both customer satisfaction and contact center operations is to implement a comprehensive queue management solution that includes both First In, First Out and scheduled callbacks and focuses on the customer experience while improving the contact center's performance.

A good virtual queuing solution will integrate with a call center’s existing technologies, such as CTI, workforce management and skill-based routing, to maximize the benefits of all systems, making it an integral part of a comprehensive queue management strategy.

Applications

Some utility companies (electric, natural gas, telecommunications, and cable television) use virtual queuing to manage seasonal peaks in call center traffic, as well as unexpected traffic spikes due to weather or service interruptions. Call centers that process inbound telesales calls can reduce the number of abandoned calls. Customer care organizations use virtual queuing to enhance service levels and increase customer loyalty. Insurance claims processing centers use virtual queuing to manage unforeseen peaks due to natural disasters.

Various amusement parks around the world have employed a similar virtual queue system for guests wishing to queue for their amusement rides. One of the most notable examples is Disney's Fastpass which issues guests a ticket which details a time for the guest to return and board the attraction. More recent virtual queue system have utilised technology, such as the Q-Bot, to reserve a place for them in the queue. Implementations of such a system include the Q-Bot at Legoland parks, the Flash Pass at Six Flags parks and the Q4U at Dreamworld.

Virtual queueing apps allow small businesses to operate their virtual queue from an app. Their customers can take virtual queue number remotely and wait remotely instead of waiting on-premises.

See also

References

- Dan Merriman, The Total Economic Impact Of Virtual Hold’s Virtual Queuing Solutions, Forrester Research, 2006

- David Maister, The Psychology Of Waiting In Lines, 1985

- Mukta Kampllikar, Losing Wait, TMTC Journal of Management, 2005

- Greg Levin, The Viability of Virtual Queuing Tools, CallCenter Magazine, 2006

- Eric Camulli, How to Optimize Skills-Based Routing Using a Virtual Queue, Connections Magazine, Jan/Feb 2007

- Jon Arnold, Virtual Queuing – the End of Music on Hold?, Focus, Dec 2010

- Shai Berger, Virtual Queuing Reaches A Turning Point, April 2012

- Padraig McTiernan, The Business Case for Virtual Queueing, June 2012

- Tom Oristian, Virtual Queuing Simulator, Aug 2012