Virial coefficient

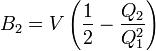

Virial coefficients  appear as coefficients in the virial expansion of the pressure of a many-particle system in powers of the density, providing systematic corrections to the ideal gas law. They are characteristic of the interaction potential between the particles and in general depend on the temperature. The second virial coefficient

appear as coefficients in the virial expansion of the pressure of a many-particle system in powers of the density, providing systematic corrections to the ideal gas law. They are characteristic of the interaction potential between the particles and in general depend on the temperature. The second virial coefficient  depends only on the pair interaction between the particles, the third (

depends only on the pair interaction between the particles, the third ( ) depends on 2- and non-additive 3-body interactions, and so on.

) depends on 2- and non-additive 3-body interactions, and so on.

Derivation

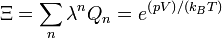

The first step in obtaining a closed expression for virial coefficients is a cluster expansion[1] of the grand canonical partition function

Here  is the pressure,

is the pressure,  is the volume of the vessel containing the particles,

is the volume of the vessel containing the particles,  is Boltzmann's constant,

is Boltzmann's constant,  is the absolute

temperature,

is the absolute

temperature, ![\lambda =\exp[\mu/(k_BT)]](../I/m/ec085976b14dcbeb5e2ecc7655efa2b6.png) is the fugacity, with

is the fugacity, with  the chemical potential. The quantity

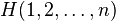

the chemical potential. The quantity  is the canonical partition function of a subsystem of

is the canonical partition function of a subsystem of  particles:

particles:

Here  is the Hamiltonian (energy operator) of a subsystem of

is the Hamiltonian (energy operator) of a subsystem of

particles. The Hamiltonian is a sum of the kinetic energies of the particles

and the total

particles. The Hamiltonian is a sum of the kinetic energies of the particles

and the total  -particle potential energy (interaction energy). The latter includes pair interactions and possibly 3-body and higher-body interactions.

The grand partition function

-particle potential energy (interaction energy). The latter includes pair interactions and possibly 3-body and higher-body interactions.

The grand partition function  can be expanded in a sum of contributions from one-body, two-body, etc. clusters. The virial expansion is obtained from this expansion by observing that

can be expanded in a sum of contributions from one-body, two-body, etc. clusters. The virial expansion is obtained from this expansion by observing that  equals

equals  .

In this manner one derives

.

In this manner one derives

![B_3 = V^2 \left[ \frac{2Q_2}{Q_1^2}\Big( \frac{2Q_2}{Q_1^2}-1\Big) -\frac{1}{3}\Big(\frac{6Q_3}{Q_1^3}-1\Big)

\right]](../I/m/52674b1264feba3cd81eb6ac97b12c47.png) .

.

These are quantum-statistical expressions containing kinetic energies. Note that the one-particle partition function  contains only a kinetic energy term. In the classical limit

contains only a kinetic energy term. In the classical limit

the kinetic energy operators commute with the potential operators and

the kinetic energies in numerator and denominator cancel mutually. The trace (tr) becomes an integral over the configuration space. It follows that classical virial coefficients depend on the interactions between the particles only and are given as integrals over the particle coordinates.

the kinetic energy operators commute with the potential operators and

the kinetic energies in numerator and denominator cancel mutually. The trace (tr) becomes an integral over the configuration space. It follows that classical virial coefficients depend on the interactions between the particles only and are given as integrals over the particle coordinates.

The derivation of higher than  virial coefficients becomes quickly a complex combinatorial problem. Making the classical approximation and

neglecting non-additive interactions (if present), the combinatorics can be handled graphically as first shown by Joseph E. Mayer and Maria Goeppert-Mayer.[2]

virial coefficients becomes quickly a complex combinatorial problem. Making the classical approximation and

neglecting non-additive interactions (if present), the combinatorics can be handled graphically as first shown by Joseph E. Mayer and Maria Goeppert-Mayer.[2]

They introduced what is now known as the Mayer function:

and wrote the cluster expansion in terms of these functions. Here

is the interaction potential between particle 1 and 2 (which are assumed to be identical particles).

is the interaction potential between particle 1 and 2 (which are assumed to be identical particles).

Definition in terms of graphs

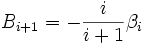

The virial coefficients  are related to the irreducible Mayer cluster integrals

are related to the irreducible Mayer cluster integrals  through

through

The latter are concisely defined in terms of graphs.

The rule for turning these graphs into integrals is as follows:

- Take a graph and label its white vertex by

and the remaining black vertices with

and the remaining black vertices with  .

. - Associate a labelled coordinate k to each of the vertices, representing the continuous degrees of freedom associated with that particle. The coordinate 0 is reserved for the white vertex

- With each bond linking two vertices associate the Mayer f-function corresponding to the interparticle potential

- Integrate over all coordinates assigned to the black vertices

- Multiply the end result with the symmetry number of the graph, defined as the inverse of the number of permutations of the black labelled vertices that leave the graph topologically invariant.

The first two cluster integrals are

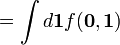

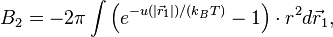

The expression of the second virial coefficient is thus:

where particle 2 was assumed to define the origin ( ).

This classical expression for the second virial coefficient was first derived by Leonard Ornstein in his 1908 Leiden University Ph.D. thesis.

).

This classical expression for the second virial coefficient was first derived by Leonard Ornstein in his 1908 Leiden University Ph.D. thesis.

See also

- Boyle temperature - temperature at which the second virial coefficient

vanishes

vanishes - Excess virial coefficient

- Compressibility factor

References

Further reading

- Dymond, J. H.; Smith, E. B. (1980). The Virial Coefficients of Pure Gases and Mixtures: a Critical Compilation. Oxford: Clarendon. ISBN 0198553617.

- Hansen, J. P.; McDonald, I. R. (1986). The Theory of Simple Liquids (2nd ed.). London: Academic Press. ISBN 012323851X.

- http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/jcp/50/10/10.1063/1.1670902

- http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/jcp/50/11/10.1063/1.1670994

- Reid, C. R., Prausnitz, J. M., Poling B. E., Properties of gases and liquids, IV edition, Mc Graw-Hill, 1987

![Q_n = \operatorname{tr} [ e^{- H(1,2,\ldots,n)/(k_B T)} ].](../I/m/159393bfd719fe06168eda10c4d33d78.png)

![f(1,2) = \exp\left[- \frac{u(|\vec{r}_1- \vec{r}_2|)}{k_B T}\right] - 1](../I/m/2db591a77a7c08cef9fe617dc505b9c4.png)