Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

- VMFA redirects here. For the VMFA designation for a Marine Fighter Attack Squadron, see List of active USMC aircraft squadrons.

|

| |

| Established | March 27, 1934 |

|---|---|

| Location | 200 N. Boulevard, Richmond, VA 23220-4007 |

| Collection size | 22,000 works (as of 2011)[1] |

| Director | Alex Nyerges |

| Public transit access | Greater Richmond Transit Company bus route 16, stop at Grove Avenue on Boulevard between Thompson and Robinson. |

| Website | |

|

Virginia Museum | |

| Coordinates | 37°33′23″N 77°28′29″W / 37.55639°N 77.47472°W |

| Built | 1936 |

| Architect | Peebles & Ferguson |

| Architectural style | Georgian Revival; English Renaissance Revival |

| Part of | Boulevard Historic District (#86002887[2]) |

| Designated CP | September 18, 1986 |

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, or VMFA, is an art museum in Richmond, Virginia, in the United States, which opened in 1936.

The museum is owned and operated by the Commonwealth of Virginia, while private donations, endowments, and funds are used for the support of specific programs and all acquisition of artwork, as well as additional general support.[3] Admission itself is free (except for special exhibits). It is one of the first museums in the American South to be operated by state funds. It is also one of the largest art museums in the North America.[4] VMFA ranks as one of the top ten comprehensive art museums in the United States.[5]

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, together with the adjacent Virginia Historical Society, anchor the eponymous "Museum District" of Richmond (alternatively known as "West of the Boulevard").[6]

History

Origins

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has its origins in a 1919 donation of 50 paintings to the Commonwealth of Virginia by Judge and prominent Virginian John Barton Payne. Payne, in collaboration with Virginia Governor John Garland Pollard and the Federal Works Projects Administration, secured federal funding to augment state funding for the museum in 1932.[7] Eventually, a site was chosen on Richmond's Boulevard. The site was toward the corner of a contiguous six-block tract of land which was then being used as an American Civil War veterans' home, with additional services for their wives and daughters (the state having earlier acquired title in exchange for helping to subsidize the operations).[8]

The main building was designed by Peebles and Ferguson Architects of Norfolk, and has been alternately described as Georgian Revival and English Renaissance, deliberately taking cues from Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren.[9] Construction began in 1934.[10] Two wings were originally planned, yet only the central portion was actually built.[10] The museum opened on January 16, 1936.[10]

Expansion and acquisitions

In 1947, the VMFA was given the Lillian Thomas Pratt Collection of some 150 jeweled objects by Peter Carl Fabergé and other Russian workshops, including the largest public collection of Fabergé eggs outside of Russia.[11] The Museum also received in 1947 the "T. Catesby Jones Collection of Modern Art". Further donations in the 1950s came from Adolph D. Williams and Wilkins C. Williams and from Arthur and Margaret Glasgow, in particular, the museum's oldest funds used for art acquisitions.

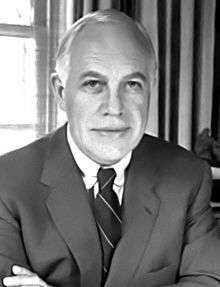

Leslie Cheek Jr., whose father built Cheekwood, became director of the museum in 1948.[12] His tenure was noted as having had a significant impact on the course of the institution; his obituary in the New York Times noted that he "transformed [the VMFA] from a small local gallery to a nationally known cultural center."[12][13]

Cheek's innovations included, in 1953, the world's first "Artmobile", a mobile tractor-trailer that housed exhibits with the purpose of reaching rural areas (prior to the presence of local museum galleries); and in 1960, in order to be accessible to a broader public, the introduction of the first night hours at an art museum.[14]

Cheek cultivated a degree of theatrical "showmanship" in the exhibits during this time, such as velvet drapery for the installation of the Fabergé collection, the "tomb-like" setting of the museum's Egyptian exhibit, and using music to set the mood in the galleries.[7][14][15][16] It was also during his time as director that the museum's first addition was built in 1954 by Merrill C. Lee, Architects, of Richmond. The wing, funded in part by Paul Mellon, included a theater, with the intent of combining the performing arts and visual arts in a single facility.[7]

Leslie Cheek Theater (Virginia Museum Theater)

The Leslie Cheek Theater, the 500-seat proscenium theater constructed in 1955 within VMFA, known originally as the Virginia Museum Theater, has seen several transitions in its 60-year history. It was designed under the supervision of director Cheek, who was a Harvard/Yale-educated architect and who consulted with Yale Drama theater engineers Donald Oenslager and George Izenour to have a state-of-the-art facility.[17] Cheek envisioned a central role for a theater arts division in the museum.[18] The theater brought the arts of drama, acting, design, music, and dance alongside the static arts of the galleries. From its beginnings through the 1960s, the Virginia Museum Theater (VMT) was the home for a VMFA sponsored volunteer or "community theater" company, under the direction of Robert Telford.[19] The company presented subscription seasons of live drama to thousands annually, with talented local players and occasional guest professionals offering many popular musical comedies (Peter Pan, e.g.), spectacular dramas (Peter Shaffer's The Royal Hunt of the Sun), and classics (Shakespeare's Hamlet). VMT also served annual programs for patrons of the Virginia Music Society, Virginia Dance Society, and Virginia Film Society.

Cheek retired from the museum in 1968 but served to advise VMFA trustees on the appointment in 1969 of Keith Fowler as the new head of the museum’s theater arts division and artistic director of VMT. Under Fowler, VMT continued to serve as the headquarters for the Dance, Film and Music Societies while he expanded live theater operations, incorporating some community actors and New-York based professionals into Richmond's first resident Actors Equity/LORT company,[20] a troupe that included core members Marie Goodman Hunter, Janet Bell, Lynda Myles, E.G. Marshall, Ken Letner, James Kirkland, Rachael Lindhart, and dramaturg M. Elizabeth Osborn. Fowler retained a focus on classics and musicals, but added an emphasis on new plays and the U.S. premieres of foreign works.

His debut production, Marat/Sade (the first racially integrated company on the VMT stage[21]), brought controversy[22] into the heart of the museum. VMT, known now as VMT Rep (for "repertory"), drew national focus when in 1973 Fowler's staging of Macbeth, starring E.G. Marshall, led Clive Barnes of The New York Times to hail it as the "'Fowler Macbeth'... "splendidly vigorous... probably the goriest Shakespearean production I have seen since Peter Brook's 'Titus Andronicus'."[23] As Fowler expanded the professionalism of the theater, VMT led Richmond into what some recall as a golden age of theater—especially in that in his time the company commissioned and produced eight American and World Premieres and introduced new plays by Pinter, Orton, Fugard, and Handke. International attention arrived in 1975[24] when the Soviet Arts Consul provided coverage on Moscow Television for Fowler's U.S-premiere of Maxim Gorky's Our Father (originally Poslednje),[25] a VMT production which went on to a New York City premiere at the Manhattan Theater Club.[26]

Over eight years, VMT's subscription audience grew from 4,300 to 10,000 patrons. Fowler resigned in 1977 in a dispute with VMFA administration over the content in VMT's premiere of Romulus Linney's Childe Byron. Successive artistic directors Tom Markus and Terry Burglar renamed the company and its playhouse "TheatreVirginia." As with all American professional not-for-profit performing arts organizations, TheatreVirginia ran mounting deficits for years,[27] underwritten by trustees. In 2002, the burden of operating in a state-supported museum (and with an audience suddenly panicked to stay at home during a series of regional sniper attacks[28]) forced TheatreVirginia to close its doors.[29] For eight years the theater lay dormant, until revived in 2011 as the Leslie Cheek Theater.

The theater's renovation and reopening[30] have reintroduced live performing arts to the heart of the Virginia Museum. At present the Leslie Cheek Theater does not support a resident company, but remains available for special theater, music, film, and dance showings.[31]

More additions

The second addition, the South Wing, was designed by Baskervill & Son Architects of Richmond and completed in 1970. It featured four new permanent galleries and a large gallery for loan exhibitions, as well as a new library, photography lab, art storage rooms and staff offices. A gift of funds from Sydney and Frances Lewis of Richmond in 1971, provided for the acquisition of Art Nouveau objects and furniture.

In 1976, a third addition, the North Wing, was completed. Designed by Hardwicke Associates, Inc., Architects, of Richmond. Adjacent to this was built a sculpture garden with a cascading fountain by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin.[32] The wing served as the new main entrance for the museum, with a separate dedicated entrance for the theater. It also added three more gallery areas – two for temporary exhibitions and one for the Lewis Family's Art Nouveau Collection, as well as a members' dining room, gift shop, and other visitor functions. However, the curved walls of its "kidney-shaped" design proved to be functionally awkward and impractical, a factor in its later replacement.[7][9] Eventually, the 1976 wing and sculpture garden were demolished to make room for the 2010 McGlothlin Wing.

In the following years, the Lewises and the Mellons proposed major donations from their extensive private collections, as well as helping to provide the funds to house them. In December 1985, the museum opened its fourth addition, the 90,000 square feet (8,400 m2) square foot West Wing.[33] The architects, Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates of New York, were chosen by the Lewis's following their 1981 design for the Best Products headquarters building north of Richmond.[7] The wing now houses their respective collections.

Redesigned campus

|

Home For Confederate Women | |

|

| |

| Location | 301 N. Sheppard St., Richmond, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Area | 2 acres (0.81 ha) |

| Built | 1932 |

| Architect | Lee,Merrill |

| Architectural style | Federal, Federal Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 85002767[2] |

| VLR # | 127-0380 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 7, 1985 |

| Designated VLR | April 16, 1985[34] |

By the 1990s, the functions of the Confederate Home for Women had ceased, and its last residents moved out.[35] In 1999, the Center for Education and Outreach (now the Pauley Center), housing the museum's Office of Statewide Partnerships, opened in the former women's home. Eventually, the remainder of the veterans camp property was transferred between state agencies to the museum, allowing it create a unified plan (begun in 2001) for what now totaled 13 1/2 acres of land in an otherwise built-out residential part of the city.[7] In 1993, the Commonwealth of Virginia transferred the care of the Robinson House from the Department of General Services to VMFA.[36]

In May 2010, the museum opened a $150-million[37] building expansion, adding 165,000 square feet (15,300 m2), increasing the museum’s gallery space by nearly 50 percent. Whereas the 1976 wing had faced inward toward a parking lot, the new wing re-oriented the entrance to the Boulevard, in addition to reopening the original 1936 entrance. The design includes a three-story atrium named for Louise B. and J. Harwood Cochrane with a 40-foot (12 m)-tall glass wall to the east and broad expanses of glass walls to the west, and a partially glazed roof.[38] The London-based architect Rick Mather partnered with Richmond-based SMBW Architects in the design of the building, while landscape architecture was handled by OLIN.[37] Landscaping included a new 4-acre (16,000 m2) sculpture garden named for philanthropists E. Claiborne and Lora Robins.[37] The new wing is named in honor of patrons James W. and Frances G. McGlothlin; the major focus of the wing is on American art, and to support the installation and interpretation of its American collections, in 2008 the museum received a $200,000 grant from the Luce Foundation.[39] The expansion received one of the 2011 RIBA International Awards for architecture.[40]

Permanent collection

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has divided its encyclopedic collections into several broad curatorial departments, which largely correspond to the galleries:[41][42]

- African Art: In 1994 and 1995, the museum exhibited its entire 250-object African art collection in "Spirit of the Motherland: African Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts." As of 2011, the collection has grown to around 500 objects, with particular strengths in the art of the Kuba, the Akan, the Yoruba, and the Kongo peoples, and the art of Mali.[43]

- American art: The American art collection began with twenty works of the John Barton Payne donation.[44] Since the 1980s, the museum has begun to systematically build its holdings in American art, aided in 1988 by the creation of an endowment to make such acquisitions by patrons Harwood and Louise Cochrane.[44]

- In 2005, the McGlothlin family promised a bequest of their collection of American art and financial support, valued at well above $100 million.

- Ancient American art

- Ancient art: Begun in 1936, the Ancient collection expanded under Director Leslie Cheek, with the advice of the Brooklyn Museum and other institutions.[45] The collection consists of works from the Ancient Egyptian, Ancient Greek, Phrygian, Etruscan, Ancient Roman, and Byzantine civilizations.[46] It includes one of two ancient Egyptian mummies in the city of Richmond, "Tjeby" (the other is at the University of Richmond).[45][47]

- Art Nouveau & Art Deco: Begun from the core collection of furniture and decorative arts the Lewis family began assembling in 1971; today it includes Art Nouveau works by Hector Guimard, Emile Galle, Louis Majorelle, Louis Comfort Tiffany, works by the Vienna Secession and Peter Behrens, Arts & Crafts works by Charles Renee Mackintosh, Frank Lloyd Wright, Stickley, and Greene & Greene, and Parisian Art Deco pieces by Eileen Gray and Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann.[16]

- East Asian art: Begun in 1941, the East Asian collection consists of Chinese, Japanese and Korean art. The collection includes Chinese jade, bronzes and Buddhist sculpture, Japanese sculpture, paintings from Kyoto, as well as Korean ceramics and bronzes from two private collections. In 2004, the collection added two stunning imperial Buddhist paintings from the Qing dynasty, dating from 1740. The collection also includes the Rene and Carolyn Balcer Collection of works by the Japanese woodblock artist Kawase Hasui – that collection consists of some 800 works, woodblock prints, screens, watercolors and other works by Hasui, including beautiful, rarely seen prints made by Hasui prior to the 1923 earthquake that destroyed half of Tokyo.[48]

- European art: The European collection began with the original 1919 Payne donation, and has since grown to include works by Bacchiacca, Murillo, Poussin, Rosa, Gentileschi, Goya,and Bouguereau.[16]

- In 1970, Ailsa Mellon Bruce donated some 450 European decorative objects, including a group of 18th- and 19th-century gold, porcelain and enamel boxes.

- Paul Mellon's donations added to this French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works and a collection of British Sporting Art, given to the museum in 1983. At his death in 1999, Mellon bequeathed additional French and British works, including five paintings by George Stubbs.

- English silver: In 1997 a collection of 18th and 19th century English silver was given to the museum by Jerome and Rita Gans.

- Fabergé The Pratt Fabergé collection, the largest collection of Fabergé eggs outside of Russia, includes five Imperial Easter Eggs: the Rock Crystal Egg of 1896, the Pelican Egg of 1898, the Peter the Great Egg of 1903, the Tsarevich Egg of 1912, and the Red Cross with Imperial Portraits Egg of 1915.[11]

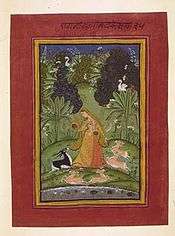

- The South Asian collection comprises works from what is today India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Tibet. The collection began in the late 1960s, with the initial core of the Himalayan collection coming in 1968.[49] When the 2010 wing was completed, a 27-ton marble late-Mughal garden pavilion from Rajasthan was installed inside the galleries.[50]

- Modern & Contemporary: The core of the Modern & Contemporary collection was assembled by Sydney and Frances Lewis in the mid- to late-20th century. Much of the more than 1,200 works in their collection were acquired by trading products (such as appliances and electronics) from their company, Best Products, to artists in exchange for works, while at the same time befriending many of them.[33][51]

Gallery

-

Peter Paul Rubens, Study for Pallas and Arachne, 1636–37

-

Artemisia Gentileschi, Cupid and Venus

-

Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Portrait of the Comte de Vaudreuil, 1784

-

Angelica Kauffman, Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, 1785

-

Junius Brutus Stearns, Washington as Farmer at Mount Vernon, 1851

-

Eugène Delacroix, Amadis Delivers Princess Olga from Galpans Castle, 1860

-

Gustave Caillebotte, Boater Docking His Skiff, 1878

-

Henri Rousseau, Tropical Landscape: American Indian Struggling with a Gorilla, 1910

-

John Singer Sargent, The Sketchers, 1914.

Special exhibitions

In addition to the galleries that display selections of the permanent collection, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts presents special exhibitions of artwork drawn from its own and others' collections, as well as work of active artists.

In 1941, the museum presented an exhibition of Modernist works by artists of the School of Paris from the collection of Walter P. Chrysler Jr. (which later became the basis for the Chrysler Museum of Art).

In the 1950s, VMFA originated shows such as "Furniture of the Old South" (1952), "Design of Scandinavia" (1954) and "Masterpieces of Chinese Art" (1955). In the 1960s, there were "Masterpieces of American Silver", followed by "Painting in England, 1700–1850," which drew heavily from the private collections of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon and was at that time the most comprehensive exhibition of British painting ever presented in the United States. In 1967, the museum also mounted a major exhibition of the work of the English social satirist William Hogarth.

In 1978, the museum presented an exhibition on Colonial cabinetmaking in early Virginia, "Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790." Another first, and one that received widespread international attention, was the 1983 exhibition "Painting in the South: 1564–1980."

In the fall of 1996, VMFA was one of five major American museums to present "Fabergé in America" and "The Lillian Thomas Pratt Collection of Fabergé." These two exhibitions, featuring more than 400 objects and 15 imperial Easter eggs, drew more than 130,000 visitors to Richmond.

In 1999, the museum presented "Splendors of Ancient Egypt," an exhibition assembled from the renowned collection of the Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, Germany. Nearly a quarter of a million people saw the show in Richmond. It was one of the largest exhibitions of Egyptian art ever to tour the United States.

In 2011, VMFA was one of the seven museums worldwide chosen to display and exhibit one hundred seventy-six paintings from the personal collection of Pablo Picasso. The exhibit was scheduled to run from February 19 – May 15, 2011 in ten galleries of the newly renovated museum. In speaking of the exhibit, director Alex Nyerges noted: "An exhibition this monumental is extremely rare, especially one that spans the entire career of a figure who many consider the most influential, innovative and creative artist of the 20th century." The collection of paintings is from a permanent collection housed in the Musée Picasso, now under renovation. The Paris museum was opened in 1985 to exhibit Picasso's collection of his personal favorite work, dating from 1881 to 1973.[52]

The VMFA is a member of the French Regional & American Museums Exchange (FRAME).

Programs

The Office of Statewide Partnerships delivers programs and exhibitions throughout the commonwealth via a voluntary network of more than 350 nonprofit institutions (museums, galleries, art organizations, schools, community colleges, colleges and universities). Through this program, the museum offers crated exhibitions, arts-related audiovisual programs, symposia, lectures, conferences and workshops by visual and performing artists. Included in the statewide partnership offerings is a special program of exhibitions, programs and educational resources tailored to help students meet the state's Standards of Learning.

VMFA offers in-house educational programs for students aged infant through infinity. The museum hosts studio classes in its Art Education Center, the Pauley Center, and the Studio School. The Art Education Center features two studios and a classroom, as well as gallery space used for exhibitions of students’ artwork. The Pauley center has two more studios and a digital lab. The studio school features multiple specialized studios as well as an exhibition space.[53]

Youth studio programs are offered year-round. Youth programs are divided into three categories: early childhood (ages 3 months-5 years), children’s (ages 5–12), and teen (ages 13–17). Family programs are also offered for children accompanied with an adult. Programs are offered in drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, fashion, digital arts, and mixed media.[54]

Group highlights tours are offered daily. K-12 group tours are also offered, incorporating the Virginia Standards of Learning. All college student tours of VMFA’s permanent collection — guided and self-directed — are free. Tours can be requested online.[55] VMFA also offers free online resources to educators.[56]

VMFA is undertaking a digital initiative, known as ARTshare. ARTshare is a multiyear initiative to expand the museum’s digital outreach and make its collection more accessible.[57]

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ Fellowship Program. With this year’s awards, fellowship grants will exceed a total of $5 million with 1,250 awards to Virginia artists since the program’s inception in 1940. The Virginia Museum awarded 27 fellowships to Virginia art students and professional artists in 2015-16 for a total of $162,000. The fellowship funds come from a privately endowed fund administered by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The Fellowship Program was established in 1940 through a generous contribution made by the late John Lee Pratt of Fredericksburg (the husband of Lillian Pratt, donor of the museum’s Fabergé collection). Offered through the VMFA Art and Education Division, fellowships are still largely funded through the Pratt endowment and supplemented by gifts from the Lettie Pate Whitehead Foundation and the J. Warwick McClintic Jr. Scholarship Fund.[58] Notable recipients of VMFA fellowship grants include Vince Gilligan,[59] Emmet Gowin, and Nell Blaine.[60]

References

- ↑ "About the Collection". VMFA Website. Retrieved Feb 28, 2011.

- 1 2 Staff (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Agency Strategic Plan 2010–2012". Virginia Performs. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ↑ http://blogs.artinfo.com/modernartnotes/2010/05/one-of-americas-quietest-museums-quietly-expands/

- ↑ https://www.1000museums.com/museums/virginia-museum-of-fine-arts

- ↑ "History of the Museum District". Museum District Website. Museum District Association.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Slipek Jr., Edwin (March 30, 2010). "Open Indulgence". Style Weekly. Retrieved Feb 27, 2011.

- ↑ "About the Robert E. Lee Camp Confederate Soldiers' Home". Library of Virginia Website. Library of Virginia. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- 1 2 Wilson, Richard Guy (2002). Buildings of Virginia: Tidewater and Piedmont. Oxford University Press. pp. 262, 270. ISBN 0-19-515206-9.

- 1 2 3 Brownell, Charles E.; et al. (1992). The Making of Virginia Architecture. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts / University Press of Virginia. p. 382. ISBN 0-917046-33-1.

- 1 2 "Faberge Factsheet". VMFA Website. VMFA.

- 1 2 "Leslie Cheek Jr., 84; Led Virginia Museum". New York Times. December 8, 1992. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Leslie Cheek, Jr.". Dictionary of Art Historians. Retrieved Feb 27, 2011.

- 1 2 "Art: Cheek's Changes". Time Magazine. Dec 7, 1959. Retrieved Feb 27, 2011.

- ↑ O' Leary, Elizabeth; et al. (2010). American Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. University of Virginia Press. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-917046-93-3.

- 1 2 3 Barriault, Anne (April 24, 2010). "Enriched Collections". Apollo.

- ↑

- ↑ NY Times, Ibid.

- ↑ "Director of Theatre tells of Plays here in 1752," The Free Lance-Star, Fredericksburg, Virginia, November 17, 1960: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19601117&id=r6oRAAAAIBAJ&sjid=becDAAAAIBAJ&pg=806,3154572

- ↑ http://lort.web.officelive.com/default.aspx

- ↑ During Segregation, some casting of black actors occurred for race-specific roles, such as maids and other servants, but Marat/Sade was the first VMT show to include African-American performers in roles not defined by race.

- ↑ Editorial, "The Thing at the Museum," Editorial Page Richmond News Leader, October 10, 1969

- ↑ Barnes, Clive (February 12, 1973). "Stage: Fowler 'Macbeth'; A Vigorous Production Staged in Richmond The Cast". The New York Times.

- ↑ Program of the Virginia Museum Theater Repertory Company, "Our Father," February 7–22, 1975

- ↑ Translated by William Stancil, VMT's Music director.

- ↑ Gussow, Mel (1975-05-10). "Stage - Gorky's Difficult 'Our Father' - A Family Split in Two Is Under Scrutiny - Article - NYTimes.com". Select.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- ↑ http://www.sc.edu/uscpress/books/2010/3907x.pdf

- ↑ Getter, Lisa, Vicki Kemper and Jonathan Peterson (2002-10-04). "5 Shot Dead in Suburban D.C. as Fear Spreads," Los Angeles Times

- ↑ http://www.playbill.com/news/article/78912-TheatreVirginia-Closes-Its-Doors-After-50-Years-Citing-Money-Woes-Loss-of-Home-Sniper

- ↑ Miller, Matthew, "Arts and Events," 05/22/2011, http://www.gayrva.com/arts-culture/theater-review-art-at-vmfa’s-leslie-cheek-theater/

- ↑ http://www2.timesdispatch.com/entertainment/2012/feb/19/tdflair02-richmond-area-arts-and-entertainment-eve-ar-1692062/

- ↑ "Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Sculpture Garden". Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- 1 2 Kollatz Jr., Harry (May 2010). "The West Wing Opens". Richmond Magazine. Retrieved Feb 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ "For Richmond's Confederate Home for Women, It's Finally Appomattox". New York Times. August 25, 1989. Retrieved Feb 27, 2011.

- ↑ Elizabeth L. O’Leary, Marc Wagner, and Kelly Spradley-Kurowski (July 2013). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Robinson House" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- 1 2 3 "Débuts". Museum (Washington D.C., USA: American Association of Museums) 89 (4): 17. July–August 2010.

- ↑ "Expansion Fact Sheet". Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ↑ "American Art: Recent Grants- 2008". Henry Luce Foundation. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ↑ "RIBA International Award winners 2011 announced". May 19, 2011. RIBA. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ↑ "About the Collection: Curators". VMFA Website. Retrieved Feb 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Collections". VMFA Website. Retrieved Feb 27, 2011.

- ↑ "African Art Collection Factsheet". VMFA Website. VMFA. Retrieved Mar 2, 2011.

- 1 2 Yount, Silvia (2010). "Introduction". American Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. University of Virginia Press.

- 1 2 Proctor, Roy (May 23, 1999). "Under 'Splendors' Spell". Richmond Times-Dispatch.

- ↑ "Ancient Art Factsheet". VMFA Website.

- ↑ "Classical Department displays 2,700-year-old mummy". The Collegian. February 26, 2009. Retrieved Feb 27, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.apollo-magazine.com/features/5939988/part_3/enriched-collections.thtml

- ↑ "Himalayan Factsheet". VMFA Website. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

- ↑ Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. "Installation of the Indian Garden Pavilion (time-lapse)". Youtube. Retrieved Mar 1, 2011.

- ↑ Murray, Elizabeth (Fall 2005). "Jennifer Bartlett". Bomb.

- ↑ Rea, F. T. (February 18, 2011). "Picasso's Richmond Period". richmond.com. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ↑ http://vmfa.museum/programs/

- ↑ http://vmfa.museum/youth-studio/

- ↑ http://vmfa.museum/tours/

- ↑ http://www.vmfa-resources.org/

- ↑ http://vmfa.museum/support/artshare/

- ↑ http://vmfa.museum/pressroom/vmfa-awards-5-million-virginia-artists-past-75-years/

- ↑ http://vmfa.museum/programs/75th-anniversary/fellowship-recipients-now/

- ↑ https://vmfa.museum/programs/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2015/01/PDF-VMFA-Fellowship-Recipients-in-Permanent-Collection-2007_v2.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. |

- Virginia Museum of Fine Arts official website

- Virginia Museum of Fine Arts history

- VMFA profile on the FRAME website

- Architectural images of the museum, prior to the 2005–2010 expansion, including the now-demolished 1976 wing

Coordinates: 37°33′25″N 77°28′26″W / 37.55698°N 77.47396°W